When the Chilean military overthrew Allende’s democratically elected government on Sept. 11, 1973, U.K. officials worked with the new junta as it committed widespread atrocities, declassified files show, Mark Curtis reports.

Bombing of Chilean presidential palace during U.S.-backed coup, Sept. 11, 1973. (Library of the Chilean National Congress/Wikipedia)

By Mark Curtis

Declassified UK

- “For British interests… there is no doubt that Chile under the junta is a better prospect than Allende’s chaotic road to socialism,” the foreign secretary said

- “The prospects for British business in Chile are clearly much brighter under the new regime,” Britain’s ambassador in Santiago agreed

- U.K. and U.S. officials feared Allende’s successful economic policies could be replicated throughout Latin America

This is an edited extract from Mark Curtis’ book, Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses, which includes full sources.

On 11 September 1973, a democratically-elected Chilean government under President Salvador Allende was overthrown in a brutal coup organised by the Chilean military with the backing of the C.I.A.

On 11 September 1973, a democratically-elected Chilean government under President Salvador Allende was overthrown in a brutal coup organised by the Chilean military with the backing of the C.I.A.

The presidential palace was rocketed by the military and Allende committed suicide. Thousands of people were imprisoned, Congress was suspended and all political parties and the trade union movement were banned.

General Augusto Pinochet soon emerged as the leader of the military junta as summary executions took place throughout the country. At least 3,000 people were soon killed, most executed, died under torture or “disappeared.”

Pinochet went on to rule Chile for 17 years. His regime became one of Latin America’s most repressive and bloody in modern history.

After the fall of the dictatorship in 1990, a truth commission confirmed that more than 40,000 people were tortured and over 200,000 fled into exile.

Declassified British files show U.K. officials described the 1973 coup as “cold-blooded” and “ruthless.” It was widely condemned throughout the world as an illegitimate overthrow of a progressive government.

It also elicited much public outrage, including among the British public, especially as the Edward Heath government did nothing in public to strongly condemn the coup.

In fact, in private his Conservative government strongly supported it, the declassified files at the National Archives show.

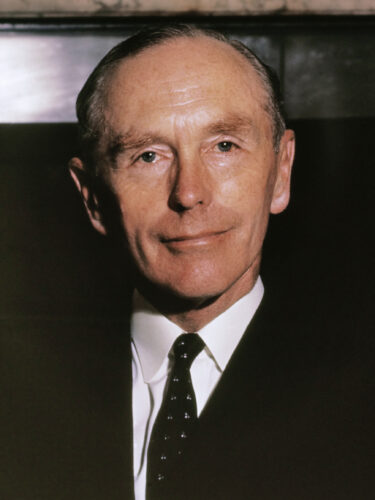

Heath, right, with Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, centre, at theRoyal Opera House, London, January 1973. (No. 10 Downing, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

‘Good Relations’

British planners in London and Santiago, Chile’s capital, immediately set about forging good relations with the new military rulers as repression increased, even secretly conniving with the junta to mislead the British public.

Officials were completely aware of the scale of atrocities. Three days after the coup, Ambassador Reginald Secondé reported to the Foreign Office that “it is likely that casualties run into the thousands, certainly it has been far from a bloodless coup.”

Six days after, he noted that “stories of military excesses and mounting casualties have begun increasingly to circulate. The extent of the bloodshed has shocked people.”

But it did not appear to shock Secondé and his staff in Santiago. He immediately reported that “we still have enough at stake in economic relations with Chile to require good relations with the government in power.”

But he suggested those good relations should be kept secret, writing: “It would not be in anyone’s interests to identify too closely with those responsible for the coup.”

‘Orderly Government’

Allende in 1970. (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 cl)

After cabling London about casualties reaching into the thousands, Secondé further told the Foreign Office that “whatever the excesses of the military during the coup” the Allende government had been leading the country into “economic ruin.”

Therefore, Britain should welcome the new rulers since “there is every reason to suppose that they will now… try to impose a period of sensible, orderly government.”

Indeed, Secondé effectively condoned the political repression, noting that “the lack of political activity is, for the time being, no loss.”

The ambassador also told the Foreign Office that “most British businessmen… will be overjoyed at the prospect of consolidation which the new military regime offers.” British companies, such as Shell, he added, “are all breathing deep sighs of relief.”

The reference was to Allende’s nationalisation campaign that had taken over some key Western commercial interests in the country, notably copper, the country’s principal economic resource.

“Now is the time to get in,” he recommended, while urging the British government to provide early diplomatic recognition of the new regime.

‘Better Prospect’

The foreign secretary in Edward Heath’s Conservative government, Alec Douglas Home, sent an official “guidance” memorandum to various British embassies on 21 September outlining British support for the new junta.

It said: “For British interests… there is no doubt that Chile under the junta is a better prospect than Allende’s chaotic road to socialism, our investments should do better, our loans may be successfully rescheduled, and export credits later resumed, and the sky-high price of copper (important to us) should fall as Chilean production is restored.”

Indeed, the Foreign Office decided to go to extraordinary lengths to assure the Chilean junta of Britain’s desire for good relations.

Eleven days after the coup, Secondé met Admiral Huerta, the junta’s new foreign minister. The ambassador’s briefing notes for this meeting state that:

“I shall put it to him frankly that HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] understands the problems which the Chilean armed forces faced before the coup and are now facing: this is a particular reason why they are anxious to enter early into good relations with the new government.”

Then Secondé said he would refer to “our own problems of public opinion at home. It would therefore help us if he [ie, Huerta] could agree that we should be able to say something to reassure public opinion at home.”

Secondé’s record of his meeting with Huerta confirms that he said that the British government “understood the motives of the armed forces, intervention and the problems facing the military government” – diplomatic language for support for the junta.

The British ambassador then gave Huerta a draft form of wording to be used in public by the U.K. government, to which Huerta was asked to agree.

Agreed Statement

Sir Alec Douglas-Home, circa 1963. (Anefo – Nationaal Archief, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

This agreed statement was an apologia for what the military junta was then doing, undertaken in order to placate public opinion in Britain.

It said Britain accepted that the internal situation in Chile “is of course a matter for the Chilean government only” and that the U.K. ambassador had expressed “the very strong feeling which exists in many quarters in Britain over the deaths of President Allende and others and over the many people arrested.”

It added that “the Chilean government offered assurances that they will deal in a humane manner” with those in detention and in political opposition — an obvious lie, since Secondé and Whitehall were perfectly aware of the scale of atrocities being committed.

Douglas Home was delighted with Secondé’s success in reaching agreement with the junta on a form of words. He cabled the ambassador praising him for carrying out a “difficult brief,” adding: “The statement helped us to defend our relatively early recognition of the new government against domestic criticism.”

‘Proper Perspective’

The removal of the democratically elected government was explained away by Secondé. He said in a reflective 20-page dispatch three weeks after the coup that “the overthrow of constitutional government was not what it may seem in Britain.”

While he recognised that the armed forces were being widely condemned internationally “this must be put into its proper perspective.”

Secondé’s analysis referred to the regular defeats Allende’s government suffered in the Congress and the government’s retention of power on the basis of the 36 percent of the vote won by Allende in the 1970 presidential election, which, Secondé was convinced, would never happen in Britain.

As for the new military junta, Secondé noted that “circumstances also will push them into directions which British public opinion will deplore” and “the next few years may be grey ones, in which freedom of expression may suffer.”

“But this regime suits British interests much better than its predecessor,” he concluded, adding: “The prospects for British business in Chile are clearly much brighter under the new regime… The new leaders are unequivocally on our side and want to do business, in the widest sense, with us.”’

This was in the context of clear recognition by British planners that “torture is going on in Chile” and also of the “allegedly quasi-fascist inclination of the new leaders.”

It was also recognised, as Secondé noted above, that the new regime was going to continue to be repressive for a long while. As one Foreign Office official noted: “It seems very hard to foresee a return for many years to anything like democratic government of the kind to which Chile has been accustomed for many years to come.”

Aiding the Regime

Pinochet, third from left in front row, at an event with background imagery comparing the year of Chilean independence, 1810, with 1973, the year of the coup d’état that brought him to power. (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 cl)

Foreign Minister Leo Amery made clear in private meetings with Judith Hart, Labour’s shadow minister for overseas development, that the U.K. aid programme and credit lines would not be suspended, as some donors had done.

In reply to a parliamentary question, the Foreign Office drafted:

“Our priorities in Latin America are determined largely by our trading and investment interests… On the recent events in Chile, our public policy is to refuse to be drawn into the controversy of the rights or wrongs of President Allende’s government or the new military government.”

The issue of British arms exports to the junta was especially pertinent since Hawker Hunter aircraft supplied by Britain had been used in the coup to attack Allende’s presidential palace and his residence.

The ambassador noted that “Hawker Hunters swept down with their aerial rockets, directed with remarkable accuracy at the palace, which was severely damaged and set on fire.”

With the junta in power, British officials made clear that arms contracts agreed with Allende would be honoured, involving eight Hawker Hunters and other equipment worth over £50 million.

Donate to CN’s Fall Fund Drive

But they went further, saying in the secret files that “we shall want in due course to make the most of the opportunities which will be presented by the change in government.”

Expectations were for new requests for arms from the junta but “we shall wish to play these as quietly as possible for some time to come” owing to widespread public opposition.

The Heath government defied calls from the Labour Party to impose an arms embargo on Chile and all the Hawker Hunters had been delivered by the time of the 1974 British general election.

A further major task was to counter the British and international opposition to the military regime’s atrocities.

‘Atrocity Stories’

Villa Grimaldi, one of the largest torture centers during the Pinochet military dictatorship. (Wikimedia Commons)

One extraordinary note by Foreign Office official Hugh Carless to Secondé, in December 1973, stated that

“unfortunately, there is (as you have pointed out to us) a good deal of fact behind the atrocity stories and that alone makes it impossible for us to counter the propaganda.”

“We can do little about the press,” he added “but you can assure them [the Chilean junta] that we and our ministers do understand the facts.”

Carless also mused that “Chileans must be wondering why on Earth… so much unfair attention is being paid to their change of government.”

He continued by noting that due to the emergence of a worldwide Chile Solidarity Movement protesting against the new regime, “we shall, occasionally, have to adopt a lower profile than we would like.”

This was especially the case in providing arms, helping the junta with debt relief and to “rescue them from being pilloried in international meetings.”

‘Violent Revolution’

The impact of the coup on Chileans was harsh. But the removal of a popular government may also have had another effect beyond the country, signalling that a peaceful, democratic path to improving the position of the poor in a developing country would be met by violence.

Ambassador Secondé noted in a dispatch after the coup that “the final seal of failure has now been put on this experiment by the Chilean armed forces.”

“This has some obvious advantages,” he noted, but also disadvantages, one of which was that “it will be widely concluded that violent revolution is the only effective way to communism.”

Douglas Home similarly suggested that “the overthrow of Allende has ruined prospects for social change to be achieved democratically in Latin America.”

‘Our Major Interest Is Copper’

A Foreign Office brief noted that “our major interest in Chile is copper,” which accounted for one third of the U.K.’s copper imports.

The disruption in Chile under Allende and “fear for the future” had recently meant large rises in copper prices which were costing the U.K. an extra £500,000 in foreign exchange. “We therefore have a major interest in Chile regaining stability, regardless of politics,” the Foreign Office stated.

Allende’s primary heresy as seen from London and Washington was nationalisation.

In July 1971 the copper industry — which provided 70 percent of Chile’s export earnings — was fully nationalised and the U.S.-owned copper mines taken over by the government, with the unanimous approval of the Congress.

Chilean workers marching in 1964 to support electing Allende as president. (James N. Wallace, U.S. Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)

The U.S. reacted sharply and cut off all credit and new aid to the government and pressed the World Bank to do the same. The chief U.S. mining corporations, Kennecott and Anaconda, began legal proceedings against the government.

The U.S. ambassador, Nathaniel Davis, told Reginald Secondé that the U.S. government was concerned

“not only about the loss to the copper companies, but also about the precedent that the Chilean action would set for the nationalisation of other big American interests throughout the developing world.”

Several banks were also nationalised while in early 1972 the government announced its intention to take over 91 key firms which accounted for around half of Chile’s economic output.

A British Conservative Party briefing paper noted that U.K. companies had been affected by nationalisation “but it was generally considered at the time that where nationalisation of British assets had taken place the compensation agreed upon had been fair.”

In a despatch just eight days before the coup, Secondé admitted that Chile “‘has at least caught her social problems by the tail: many people in the poorer and most depressed sections of the community have, as a result of President Allende’s administration, attained a new status and at least tasted, during its early days, a better standard of living, though it has been eroded by inflation.”

Secondé concluded that “this is a major achievement and has set Chile apart from most other Latin American states.”

Threat of a Good Example

Allende in 1972. (Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons)

Yet it was precisely because Allende’s government was being successful that British and U.S. planners wanted him to be removed.

After being elected in 1970, Allende was appointed president of a Popular Unity government with the consent of the Christian Democratic Party. He inherited an economy that, as in most of Latin America, was controlled by a small elite.

In his victory speech in November 1970 Allende proclaimed a programme for fundamental economic change, proposing to abolish the monopolies “which grant control of the economy to a few dozen families.”

He also pledged to abolish the tax system that favoured the rich, abolish the “large estates which condemn thousands of peasants to serfdom” and “put an end to the foreign ownership of our industry.”

“The road to socialism lies through democracy, pluralism and freedom,” Allende proclaimed.

The strategy was to create a restructured society based on state, mixed and private ownership of resources to be achieved mainly through the rapid extension of state control over large parts of the economy, either by direct nationalisation or government investment.

These policies improved the position of the poor, especially in the early part of the Allende presidency, through raising the minimum wage and special bonuses paid to poorly paid workers.

This was matched by rising popularity for the government; in congressional elections in the year of the coup, 1973, the Popular Unity coalition increased its vote to 44 per cent.

‘Redistribution of Income’

Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) recognised “the Allende government has been directing its economic efforts primarily at effecting a redistribution of income” in which prices had been held down and salaries allowed to rise.

The strategy was “to put right what they regard as economic and social injustices (including foreign domination of certain sectors of the economy).” Allende was “committed to proving that socialism can be brought to Chile in a peaceful and democratic fashion.”

Just three months after Allende assumed office, the JIC was concluding that “Washington is clearly very perturbed by developments in Chile.”

As well as nationalisation of U.S. business interests, “the United States must view the prospect of a moderately successful extreme left-wing regime in Chile with considerable misgiving if only because of the effect this might have elsewhere in Latin America,” the JIC noted.

It also expressed the same fear from a British perspective, saying that the course of events in Chile is likely to have “important repercussions throughout Latin American and perhaps beyond.”

It added: “Allende’s victory has been hailed as strengthening the prevailing radical, anti-American trend in Latin America.” It may lead to a bloc of “like-minded states comprising Chile, Bolivia and Peru whose negative attitude towards foreign investment has already been demonstrated.”

Covert Action

Pinochet, left, greeting U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1976. (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

The C.I.A. had initially sought to prevent Allende from taking office. A declassified C.I.A. report reveals that throughout the 1960s and 1970s the U.S. promoted “sustained propaganda efforts, including financial support for major news media, against Allende.”

This included “political action projects” that “supported selected parties before and after the 1964 elections and after Allende’s 1970 election.”

In the 1960s, activities included financial assistance to the Christian Democratic Party, the distribution of posters and leaflets, and financial assistance to selected candidates in congressional elections.

By the time of the 1964 election, won by favoured U.S. candidate Eduardo Frei of the Christian Democratic Party, the C.I.A. had provided $3 million to prevent Allende winning.

In the run-up to the 1970 election won by Allende, the C.I.A. conducted “spoiling operations” to prevent his victory while President Richard Nixon authorised the agency “to seek to instigate a coup to prevent Allende from taking office.”

Declassified has revealed that Britain also conducted a covert propaganda offensive to stop Allende winning the 1964 and 1970 elections.

The Foreign Office’s Information Research Department gathered information designed to damage Allende and lend legitimacy to his political opponents, and distributed material to influential figures within Chilean society.

The IRD also shared intelligence about left-wing activity in the country with the U.S. government. British officials in Santiago assisted a C.I.A.-funded media organization, which was part of extensive U.S. covert action to overthrow Allende, culminating in the 1973 coup.

Overthrow

A few days after Allende assumed office in 1970, the C.I.A. was authorised to establish direct contacts with Chilean military officers “to evaluate the possibilities of stimulating a military coup if a decision were to be made to do so.”

A few days after Allende assumed office in 1970, the C.I.A. was authorised to establish direct contacts with Chilean military officers “to evaluate the possibilities of stimulating a military coup if a decision were to be made to do so.”

Arms, including machine guns and ammunition, were provided to one of the groups plotting a coup.

A fund of $10 million was authorised “to prevent Allende from coming to power or unseat him,” which was used to strengthen opposition political parties and assist militant right-wing groups to undermine him.

C.I.A. money was also used for planting stories in local media and promoting opposition to Allende in the Chilean press. Also approved were efforts “to encourage Chilean businesses to carry out a program of economic disruption.”

U.S. Ambassador Edward Korry explained that the strategy was to

“do all within our power to condemn Chile and the Chileans to utmost deprivation and poverty, a policy designed for a long time to come to accelerate the hard features of a communist society in Chile.”

After the Pinochet takeover, the C.I.A. notes that it “continued some ongoing propaganda projects, including support for news media committed to creating a positive image for the military junta.”

Reginald Secondé went to become British ambassador to Romania and Venezuela, before dying in 2017 at the age of 95.

Mark Curtis is the editor of Declassified UK, and the author of five books and many articles on U.K. foreign policy.

This article is from Declassified UK.

Donate to CN’s

Fall Fund Drive

Here you have some available documents:

1. Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973, released by the U.S. Department of State; printed version: United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Staff Report, Covert Action in Chile (1963-1973) (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975).

2. Peter Kornbluh, „Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup”, 11. IX. 1973, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 8.

hxxps://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/nsaebb8i.htm.

In this compendium there are: National Security Council strategy papers which record efforts to ‘destabilize’ Chile economically, and isolate Allende’s government diplomatically, between 1970 and 1973.

And here are documentary movies made in Santiago, available on the internet.

dir. Patricio Guzman: The Battle of Chile: I. The Insurrection of the Bourgeouisie, II. The Coup d’Etat, III. The Power of the People, IV. Chile Obstinate Memory.

Pablo Neruda himself fell seriously ill and died 23th September 73 in a Santiago Hospital. It is still not known wether he died from his illness or wether he has been murdered.

US citizens are still complicit in CIA-supported regime changes such as Chile on Sept 11 of 1973. After all, is not the US a democracy?

The blowback on Sept 11 of 2001 was another result of CIA and Pentagon interventions in the affairs of sovereign states in the Middle East. .

The latest intervention is the $125 billion in assistance to Ukraine for fighting a proxy war against Russia. Don’t citizens realize that spending on welfare and war is not sustainable even with unlimited printing of fiat money by the Fed?

My first reaction on seeing the photo of Sir Alec Douglas-Home was to recall Shakespeare’s observation that “One may smile and smile and be a villain” – not that Home rose beyond banality to the level of a Bond villain but was simply a government agent cheerfully ensuring that not only those who thought their government represented them but also their other alleged representatives were kept ignorant of what their government was doing in their names lest they inconvenience those activities.

As an American citizen I’m used to having such reactions to our own government’s vile behavior when the light of day eventually falls upon it but we clearly have no monopoly on this and may be somewhat better at keeping more of it hidden.

If I can react so strongly to evidence that comes to my attention a half century after the fact (I was less aware of some of the details back then) there’s some hope that others will as well – so thanks for keeping us from forgetting.

This bloody Euro/US empire can’t collapse soon enough. The world will be a far better place without these ghouls enforcing their fascist policies on humanity.

I totally agree with you!

1973 i was studying in London when many Chilenian students suddenly arrived there. They had to flee their country via different Europaen Embassies. Another place for them to go was Berlin where i also met many refugees from Chile.

Later i saw the film “Missing” by Costa Gavras , featuring the coup in Chile. It was clear then that many Americans were involved. The place was crawling with CIA Agents.

Allende did not commit suicide! He was standing at the desk in his room when Pinochets murderers stormed the Palace.

#His only weapon being his brave heart.”

These are the words written by his friend Pablo Neruda who managed to flee to Mexico.

The film is a masterpiece starring Sissy Spacek and John Lemon in search for his son who had been murdered during the coup. I highly recommend this film.