Afghanistan’s transformation into a preeminent narco-state owes a significant debt to Washington, writes Alan McLeod. Now, with a heroin shortage threatening to increase fentanyl abuse, the U.S. faces possible blowback.

Opium fields ready for harvesting in Bala Baluk, Afghanistan, 2009. (ISAF, Monica R. Nelson)

The Taliban government in Afghanistan – the nation that until recently produced 90 percent of the world’s heroin – has drastically reduced opium cultivation across the country. Western sources estimate an up to 99 percent reduction in some provinces.

The Taliban government in Afghanistan – the nation that until recently produced 90 percent of the world’s heroin – has drastically reduced opium cultivation across the country. Western sources estimate an up to 99 percent reduction in some provinces.

This raises serious questions about the seriousness of U.S. drug eradication efforts in the country over the past 20 years. And, as global heroin supplies dry up, experts tell MintPress News that they fear this could spark the growing use of fentanyl – a drug dozens of times stronger than heroin that already kills more than 100,000 Americans yearly.

Taliban Does What the US Did Not

It has already been called “the most successful counter-narcotics effort in human history.” Armed with little more than sticks, teams of counter-narcotics brigades travel the country, cutting down Afghanistan’s poppy fields.

In April of last year, the ruling Taliban government announced the prohibition of poppy farming, citing both their strong religious beliefs and the extremely harmful social costs that heroin and other opioids – derived from the sap of the poppy plant – have wrought across Afghanistan.

It has not been all bluster. New research from geospatial data company Alcis suggests that poppy production has already plummeted by around 80 percent since last year. Indeed, satellite imagery shows that in Helmand Province, the area that produces more than half of the crop, poppy production has dropped by a staggering 99 percent. Just 12 months ago, poppy fields were dominant.

But Alcis estimates that there are now less than 1,000 hectares of poppy growing in Helmand.

A U.S. Marine greeting local children working in an opium poppy field in Helmand Province, 2011. (ISAF, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Instead, farmers are planting wheat, helping stave off the worst of a famine that U.S. sanctions helped create. Afghanistan is still in a perilous state, however, with the United Nations warning that 6 million people are close to starvation.

The Taliban waited until 2022 to impose the long-awaited ban in order not to interfere with the growing season. Doing so would have provoked unrest among the rural population by eradicating a crop that farmers had spent months growing.

Between 2020 and late 2022, the price of opium in local markets rose by as much as 700 percent. Yet given the Taliban’s insistence – and their efficiency at eradication – few have been tempted to plant poppies.

The poppy ban has been matched by a similar campaign against the methamphetamine industry, with the government targeting the ephedra crop and shutting down ephedrine labs across the country.

A Looming Catastrophe

Afghanistan produces almost 90 percent of the world’s heroin. Therefore, the eradication of the opium crop will have profound worldwide consequences on drug use.

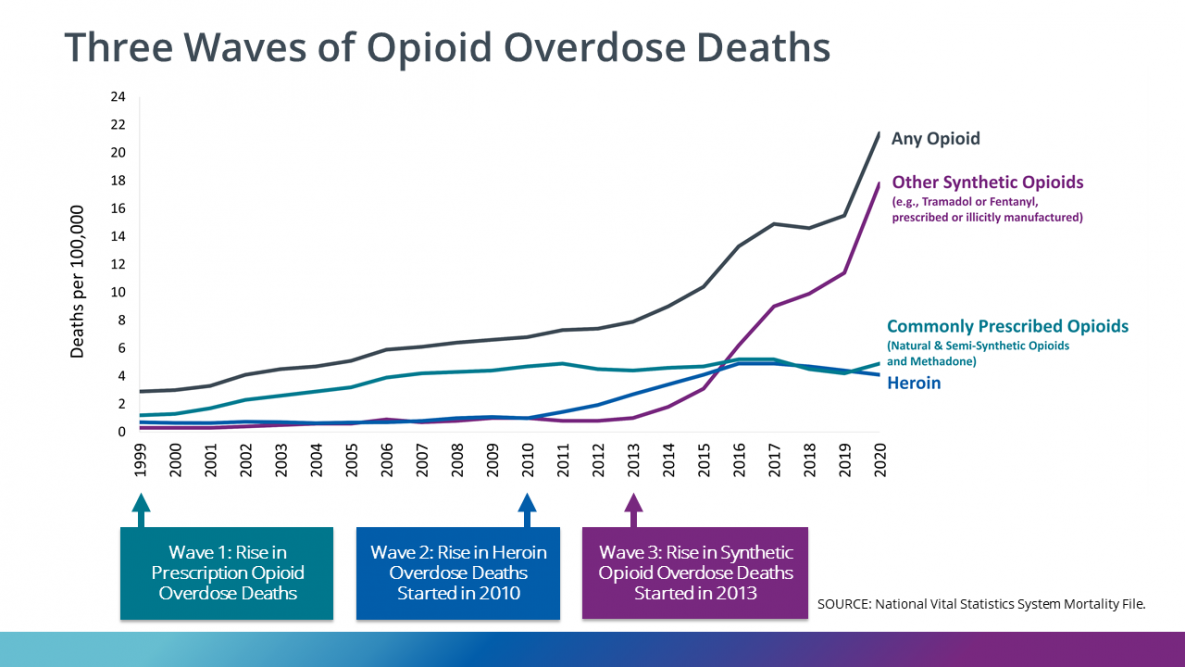

Experts MintPress spoke to warned that a dearth of heroin would likely produce a huge spike in the use of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, a drug the Center for Disease Control estimates is 50 times stronger and is responsible for taking the lives of more than 100,000 Americans each year.

“It is important to consider past periods of heroin shortages and the impact these have had on the European drug market,” the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction told MintPress, adding:

“Experience in the E.U. with previous periods of reduced heroin supply suggests that this can lead to changes in patterns of drug supply and use. This can include further an increase in rates of polysubstance use among heroin users. Additional risks to existing users may be posed by the substitution of heroin with more harmful synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and its derivatives and new potent benzimidazole opioids.”

In other words, if heroin is no longer available, users will switch to far deadlier synthetic forms of the drug. A 2022 United Nations report came to a similar conclusion, noting that the crackdown on heroin production could lead to the “replacement of heroin or opium by other substances…such as fentanyl and its analogs.”

“It does have that danger in the macro sense, that if you take all that heroin off the market, people are going to go to other products,” Matthew Hoh told MintPress. Hoh is a former State Department official who resigned from his post in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, in 2009.

“But the response should not be reinvade Afghanistan, reoccupy it and put the drug lords back in power, which is basically what people are implying when they bemoan the consequence of the Taliban stopping the drug trade,” Hoh added; “Most of the people who are speaking this way and worrying out loud about it are people who want to find a reason for the U.S. to go and affect regime change in Afghanistan.”

U.S. representative Zalmay Khalilzad (left) meeting with Taliban leaders, Abdul Ghani Baradar, Abdul Hakim Ishaqzai, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Sheila Shaheen, unidentified; Doha, Qatar, Nov. 21, 2020. (U.S. State Department)

There certainly has been plenty of hand-wringing from American sources. Foreign Policy wrote about “how the Taliban’s ‘war on drugs’ could backfire;” U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty claimed that the Taliban were turning a “blind eye to opium production,” despite the official ban.

And the United States Institute of Peace, an institution created by Congress that is “dedicated to the proposition that a world without violent conflict is possible,” stated emphatically that “the Taliban’s successful opium ban is bad for Afghans and the world.”

This looming catastrophe, however, will not hit immediately. Significant stockpiles of drugs along trafficking routes still exist. As the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction told MintPress:

“It can take over 12 months before the opium harvest appears on the European retail drug market as heroin – and so it is too early to predict, at this stage, the future impact of the cultivation ban on heroin availability in Europe. Nonetheless, if the ban on opium cultivation is enforced and sustained, it could have a significant impact on heroin availability in Europe during 2024 or 2025.”

Yet there is little indication that the Taliban are anything but serious about eradicating the crop, indicating that a heroin crunch is indeed coming.

A similar attempt by the Taliban to eliminate the drug occurred in 2000, the last full year that they were in power. It was extraordinarily successful, with opium reduction dropping from 4,600 tons to just 185 tons. At that time, it took around 18 months for the consequences to be felt in the West.

In the United Kingdom, average heroin purity fell from 55 percent to 34 percent, while in the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, heroin was largely replaced by fentanyl. However, as soon as the United States invaded in 2001, poppy cultivation shot back up to previous levels and the supply chain recommenced.

US Complicity in the Afghan Drug Trade

An Afghan Mujahid demonstrates positioning of a Soviet-built SA-7 hand-held surface-to-air missile, August 1988. (DoD, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

The Taliban’s successful campaign to eradicate drug production has cast a shadow of doubt over the effectiveness of American-led endeavors to achieve the same outcome. “It prompts the question, ‘What were we actually accomplishing there?’ ” remarked Hoh, underscoring:

“This undermines one of the fundamental premises behind the wars: the alleged association between the Taliban and the drug trade — a concept of a narco-terror nexus. However, this notion was fallacious. The reality was that Afghanistan was responsible for a staggering 80-90 percent of the world’s illicit opiate supply. The primary controllers of this trade were the Afghan government and military, entities we upheld in power.”

Hoh clarified that he never personally witnessed or received any reports of direct involvement by U.S. troops or officials in narcotics trafficking. Instead, he contended that there existed a “conscious and deliberate turning away from the unfolding events” during his tenure in Afghanistan.

Suzanna Reiss, an academic at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the author of We Sell Drugs: The Alchemy of U.S. Empire, demonstrated an even more cynical perspective on American counter-narcotics endeavors as she conveyed to MintPress:

“The U.S. has never really been focused on reducing the drug trade in Afghanistan (or elsewhere for that matter). All the lofty rhetoric aside, the U.S. has been happy to work with drug traffickers if the move would advance certain geopolitical interests (and indeed, did so, or at least turned a knowingly blind eye, when groups like the Northern Alliance relied on drugs to fund their political movement against the regime.).”

Afghanistan’s transformation into a preeminent narco-state owes a significant debt to Washington’s actions. Poppy cultivation in the 1970s was relatively limited.

Afghanistan’s transformation into a preeminent narco-state owes a significant debt to Washington’s actions. Poppy cultivation in the 1970s was relatively limited.

However, the tide changed in 1979 with the inception of Operation Cyclone, a massive infusion of funds to Afghan Mujahideen factions aimed at exhausting the Soviet military and terminating its presence in Afghanistan.

The U.S. directed billions toward the insurgents, yet their financial needs persisted. Consequently, the Mujahideen delved into the illicit drug trade. By the culmination of Operation Cyclone, Afghanistan’s opium production had soared 20-fold.

Professor Alfred McCoy, acclaimed author of The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, shared with MintPress that approximately 75 percent of the planet’s illegal opium output was now sourced from Afghanistan, a substantial portion of the proceeds funneling to U.S.-backed rebel factions.

Unraveling the Opioid Crisis: An Impending Disaster

The opioid crisis is the worst addiction epidemic in U.S. history. Earlier this year, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas described the American fentanyl problem as “the single greatest challenge we face as a country.”

Nearly 110,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2021, fentanyl being by far the leading cause. Between 2015 and 2021, the National Institute of Health recorded a nearly 7.5-fold increase in overdose deaths. Medical journal The Lancet predicts that 1.2 million Americans will die from opioid overdoses by 2029.

U.S. officials blame Mexican cartels for smuggling the synthetic painkiller across the southern border and China for producing the chemicals necessary to make the drug.

White Americans are more likely to misuse these types of drugs than other groups. Adults aged 35-44 experience the highest rates of deaths, although deaths among younger people are surging.

White Americans are more likely to misuse these types of drugs than other groups. Adults aged 35-44 experience the highest rates of deaths, although deaths among younger people are surging.

Rural America has been particularly hard hit; a 2017 study by the National Farmers Union and the American Farm Bureau Federation found that 74 percent of farmers have been directly impacted by the opioid epidemic. West Virginia and Tennessee are the states most badly hit.

For writer Chris Hedges, who hails from rural Maine, the fentanyl crisis is an example of one of the many “diseases of despair” the U.S. is suffering from. It has, according to Hedges, “risen from a decayed world where opportunity, which confers status, self-esteem and dignity, has dried up for most Americans. They are expressions of acute desperation and morbidity.”

In essence, when the American dream fizzled out, it was replaced by an American nightmare. That white men are the prime victims of these diseases of despair is an ironic outgrowth of our unfair system. As Hedges explained:

“White men, more easily seduced by the myth of the American dream than people of color who understand how the capitalist system is rigged against them, often suffer feelings of failure and betrayal, in many cases when they are in their middle years. They expect, because of notions of white supremacy and capitalist platitudes about hard work leading to advancement, to be ascendant. They believe in success.”

In this sense, it is important to place the opioid addiction crisis in a wider context of American decline, where opportunities for success and happiness are fewer and farther between than ever, rather than attribute it to individuals.

As The Lancet wrote: “Punitive and stigmatizing approaches must end. Addiction is not a moral failing. It is a medical condition and poses a constant threat to health.”

‘Uniquely American Problem’

Nearly 10 million Americans misuse prescription opioids every year and at a rate far higher than comparable developed countries. Deaths due to opioid overdose in the United States are 10 times more common per capita than in Germany and more than 20 times as frequent in Italy, for instance.

Much of this is down to the United States’ for-profit healthcare system. American private insurance companies are far more likely to favor prescribing drugs and pills than more expensive therapies that get to the root cause of the issue driving the addiction in the first place. As such, the opioid crisis is commonly referred to as a “uniquely American problem.”

Part of the reason U.S. doctors are much more prone to doling out exceptionally strong pain medication relief than their European counterparts is that they were subject to a hyper-aggressive marketing campaign from Purdue Pharma, manufacturers of the powerful opioid OxyContin. Purdue launched OxyContin in 1996, and its agents swarmed doctors’ offices to push the new “wonder drug.”

Yet, in lawsuit after lawsuit, the company has been accused of lying about both the effectiveness and the addictiveness of OxyContin, a drug that has hooked countless Americans onto opioids. And when legal but incredibly addictive prescription opioids dry up, Americans turned to illicit substances like heroin and fentanyl as substitutes.

Purdue Pharma owners, the Sackler family, have regularly been described as the most evil family in America, with many laying the blame for the hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths squarely at their door. In 2019, under the weight of thousands of lawsuits against it, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy. A year later, it plead guilty to criminal charges over its mismarketing of OxyContin.

Nevertheless, the Sacklers made out like bandits from their actions. Even after being forced last year to pay nearly $6 billion in cash to victims of the opioid crisis, they remain one of the world’s richest families and have refused to apologize for their role in constructing an empire of pain that has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Instead, the family has attempted to launder their image through philanthropy, sponsoring many of the most prestigious arts and cultural institutions in the world. These include the Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, Yale University, and the British Museum and Royal Academy in London.

One group who are disproportionately affected by opioids like OxyContin, heroin and fentanyl are veterans. According to the National Institutes of Health, veterans are twice as likely to die from overdose than the general population. One reason for this is bureaucracy.

“The Veterans Administration did a really poor job in the past decades with their pain management, particularly their reliance on opioids,” Hoh, a former marine, told MintPress, noting that the V.A. prescribed dangerous opioids at a higher rate than other healthcare agencies.

Ex-soldiers often have to cope with chronic pain and brain injuries. Hoh noted that around a quarter-million veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq have traumatic brain injuries. But added to that are the deep moral injuries many suffered — injuries that typically cannot be seen. As Hoh noted:

“Veterans are turning to [opioids like fentanyl] to deal with the mental, emotional and spiritual consequences of the war, using them to quell the distress, try to find some relief, escape from the depression, and deal with the demons that come home with veterans who took part in those wars.”

Thus, if the Taliban’s opium eradication program continues, it could spark a fentanyl crisis that might kill more Americans than the 20-year occupation ever did.

Broken Society

If diseases of despair are common throughout the United States, they are rampant in Afghanistan itself. A global report released in March revealed that Afghans are by far the most miserable people on Earth. Afghans evaluated their lives at 1.8 out of 10 – dead last and far behind the top of the pile Finland (7.8 out of 10).

Opium addiction in Afghanistan is out of control, with around 9 percent of the adult population (and a significant number of children) addicted. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of adult drug users jumped from 900,000 to 2.4 million, according to the United Nations, which estimates that almost 1-in-3 households is directly affected by addiction. As opium is frequently injected, blood-transmitted conditions like HIV are common as well.

The opioid problem has also spilled into neighboring countries such as Iran and Pakistan. A 2013 United Nations report estimated that almost 2.5 million Pakistanis were abusing opioids, including 11 percent of people in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Around 700 people die each day from overdoses.

Empire of Drugs

Given their history, It is perhaps understandable that Asian nations have generally taken far more authoritarian measures to counter drug addiction issues. For centuries, using the illegal drug trade to advance imperial objectives has been a common Western tactic.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the French utilized opium crops in the “Golden Triangle” region of Southeast Asia in order to counter the growing Vietnamese independence movement.

A century previously, the British used opium to crush and conquer much of China. Britain’s insatiable thirst for Chinese tea was beginning to bankrupt the country, seeing as China would only accept gold or silver in exchange.

The British, therefore, used the power of its navy to force China to cede Hong Kong to it. From there, it flooded mainland China with opium grown in South Asia (including Afghanistan).

The effect of the Opium War was astonishing. By 1880, the British were inundating China with more than 6,500 tons of opium per year – the equivalent of many billions of doses.

Chinese society crumbled, unable to deal with the empire-wide social and economic dislocation that millions of opium addicts brought. Today, the Chinese continue to refer to the period as the “century of humiliation.”

Meanwhile, in South Asia, the British forced farmers to plant poppy fields instead of edible crops, causing waves of giant famines, the likes of which had never been seen before or since.

And during the 1980s in Central America, the United States sold weapons to Iran in order to fund far-right Contra death squads. The Contras were deeply implicated in the cocaine trade, fuelling their dirty war through crack cocaine sales in the U.S. — a practice that, according to journalist Gary Webb, the Central Intelligence Agency facilitated.

Imperialism and illicit drugs, therefore, commonly go together.

However, with the Taliban opium eradication effort in full effect, coupled with the uniquely American phenomenon of opioid addiction, it is possible that the United States will suffer significant blowback in the coming years.

The deadly fentanyl epidemic will likely only get worse, needlessly taking hundreds of thousands more American lives.

Thus, even as Afghanistan attempts to rid itself of its deadly drug addiction problem, its actions could precipitate an epidemic that promises to kill more Americans than any of Washington’s imperial endeavors to date.

Alan MacLeod is senior staff writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academicarticles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, andCommon Dreams.

This article is from MPN.news, an award winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

As in Central America during the Bill Casey(who engineered Reagan’s New Hampshire primary jump over the Bush faction). The by-passing of Congress funding via arms and cocaine sales may indicate the Freedom Fighter may just be another name for Drug Lord. Ditto in Afghanistan against the USSR. Air America support for heroine in Vietnam. A long history related also to opium sales by US and GB in previous pivotal days to China they probably haven’t forgotten either.

The Pharmaceutical companies sell you opiates to get you addicted, then they sell you Suboxone for the rest of your life for maintenance of your addiction. Reminds me of The Space Merchants by Frederik Pohl. The corporations had three products, to cure yourself from product one you needed product two, to cure you from product two you needed product three and to cure you from product three you needed product one again. This was science fiction in 1952, now it’s grim reality.

Before US arrival in Afghanistan – Taliban reported to have all but eliminated Opium/heroin … after US departure from Afghanistan – Taliban reorted to have all but eliminated Opium/heroin …. surprise!!!!!

This is an excellent article on the drug trade, but I am disappointed that the author does not mention the fact that the CIA is largely responsible for the vast poppy fields in Afghanistan. Before the CIA decades ago sponsored the mujahadeen to annoy Russia and “weaken” it, poppy cultivation in Afghanistan was minimal. The CIA came in and got more planted. When the Taliban first took charge they eliminated that, but when we went back into Afghanistan and Iraq the CIA once again took over and ran the drug trade. Our government knew very well that when we left this time, that the Taliban would come back and eliminate the poppy fields when they could. I bet the CIA has another country all lined up to grow poppies for them; or maybe the CIA is into some other addictive drug (fentenyl?) For those interested in this problem, read the book by Paul L. Williams titled “Operation Gladio: The Unholy Alliance between the Vatican, the CIA and the Mafia” It’s a fascinating read about how Alan Dulles funded the CIA after WWII by running drugs and how that turned into the CIA running a world drug trade worth billions (which is banked in the Vatican banks to disguise it). Consortium readers, I assume, are aware that the CIA ran a major drug operation throughout the Vietnam war. Gosh, Hollywood made a movie about it “Air America”; they thought it was cool.

Williams’s “Operation Gladio” is indeed a great book on the nexus between covert operations and transnational crime syndicates engaged in narcotrafficking (among other things), as are Whitney Webb’s recent two-volume series “One Nation Under Blackmail,” Russell H. and Sylvia E. Bartley’s “Eclipse of the Assassins,” the late Gary Webb’s “Dark Alliance,” Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair’s “Whiteout,” and other books I have mentioned by Alfred McCoy, John K. Cooley, Beaty and Gwynne, and Peter Dale Scott, to name but a few.

That being said, one other book that I would add to that list highlighting the Taliban’s own complicit role in such parapolitical networks is Gretchen Peters’s “Seeds of Terror,” published in 2010.

Heroin addicts in the US were already transitioning to fentanyl before the Taliban put a stop to poppy cultivation. The reason for this was lower cost. The longstanding interdiction policy has always been a sham, as is clearly evidenced by the fact that reducing the supply of heroin on the market has done nothing to reduce the usage of opioids. Users will always find a substitute. For them, it is a necessity. Unfortunately, fentanyl has a very low therapeutic index, which is the ratio between a drug’s toxic dose and its therapeutic dose. This explains the rash of fentanyl overdose deaths.

Since the corporate media is heavily infiltrated by the CIA, it comes as no surprise we are seeing news items warning of the downside of poppy eradication in Afghanistan. Their funding will practically dry up. Can’t have the CIA holding bake sales to fund US regime change operations.

So, did I read this right? Growing opium poppies – bad. Not growing opium poppies – bad.?

What a goat rodeo.

Analgesics can be withheld for ransom prices because people hurt. Governments ban analgesics, enabling extortion. The DEA prosecutes competition; the CIA sells and barters exception.

The Taliban can stop the drug trade because they want to. The Americans do not. The Taliban want to because they are aware that the trade is an arm of the invaders and a grand funding for black operations. Similar motivations create repressive policies in many countries, which the US then criticizes for human rights violations, not always without motive, though the motives are worth suspicions.

Producer countries generally do not have the otherwise obvious option of legalization because this allows too much Agency penetration of their economies. Client states have reduced options of otherwise acceptable policies of search and seizure and trial because they are locked in a struggle with the Agency-mafia penetration of their own societies, including considerable parts of government and influential business interests.

It is because of all that the US decries drug policies of producers and insists on reproducing this sort of policy and this sort of market–which has, with alterations, continued year after year at least since the earlier Opium War between England and China in the 1800’s.

We think of this in terms of banned drug use, but of course these policies also provide for the ransom of narcotics to prescription patients. After all, we are only talking about the sap of a flower that could be grown easily across most of the US, even without particularly purposeful cultivation–grown like a weed.

My father paid for health insurance for decades before he finally took sick. The hospital was large and ample, the nurses and doctors competent in their conventional ways, though pretty busy. The one thing that anyone could do for him, finally, was an IV of morphine–he was dying, and not too improbably, at 90 years of age.

It could be legal, and this would resolve huge issues of corruption. I assume that the markets in arms and slaves would continue, but the loss of revenues would have to abate some of those practices as well. Barring legality, other herbal possibilities could reduce demand, but these are apt to be watched pretty closely at some point.

I’m so grateful to Consortium News, this is journalism at its best. It’s a shame that pieces like this will only be consumed by a minuscule percentage of the population, the other 99.99% will keep believing their msm propaganda and how the US are a good for the world.

Fentanyl will obviously end the need for a heroin market, but they are both so erratic in purity that overdose deaths will continue, as usual..

By next year, when the results of the current Taliban ban become more clear, a comparison can be made with the effects of the 2001 ban, when there was no Fentanyl..

The Afghanis will need sustainable crop alternatives, whatever they may be..

Remind me again why the C.I.A. invaded Afghanistan to begin with?

Excerpt from original comments that I made on two articles syndicated by Consortium News (Hanif Sufizada, “Taliban Are Megarich – Here’s Where They Get the Money,” Dec. 10, 2020, and Andrew J. Bacevich, “Requiem for the ‘American Century,’” Mar. 30, 2021):

I do quibble with the implication that the Taliban have not been deeply complicit in the post-invasion drug trade via their connections such as drug lord Haji Juma Khan (just as the victorious Northern Alliance and their political heirs including the Karzai dynasty have been as well), with United States acquiescence and complicity in both cases. Moreover, even in c. 2000-2001 when the Taliban was publicly collaborating with the United Nations to systematically reduce poppy yields, there is evidence that they did so primarily to hoard profits and monopolize the trade for themselves (see Donna Leinwand, et. al., “U.S. Expected to Target Afghanistan’s Opium,” USA Today, October 16, 2001). Of course, this may not have sat well with certain influential drug-trafficking interests abroad, the likes of which are chronicled in works such as Alfred McCoy’s ‘The Politics of Heroin,’ John K. Cooley’s ‘Unholy Wars,’ Jonathan Beaty and S.C. Gwynne’s ‘The Outlaw Bank,’ and the scholarship of Peter Dale Scott.

Before 2000, the Taliban certainly had no issue with opium poppy cultivation and drug trafficking, as pre-2001 UNODC figures (news.un.org/en/sites/news.un.org.en/files/legacy-news-images/photos/large/2017/November/Afghan_opium_survey-01.jpg) and this excerpt from Omar bin Laden (son of UBL) on p. 158 in Jean Sasson’s ‘Growing Up Bin Laden’ (2009) demonstrates:

‘The vast poppy fields took my mind off my troubles, and even prompted my father to demand ‘What is the meaning of this?’ as he gestured to the endless green field of poppies. We all knew they were used to make opium, which would be turned into heroin.

The driver shrugged. ‘Farmers here say that Taliban leader Mullah Omar has made a fatwa saying that the Afghan people should cultivate and sell the poppy plant, but only if it will be sold to the United States. The mullah said that his goal was to send as many hard drugs to the United States as possible so that America’s money would flow to Afghanistan while America’s youth will be ruined by becoming addicted to heroin.'”

~

“Of course, there is little incentive for certain influential covert interests to pursue [alternative anti-crime / counter-narcotic strategies, such as promotion of the Morales-era SYSCOCA model from Bolivia] in anything but an extremely adulterated form in practice, given their own complicity in the drug trade in Afghanistan and elsewhere, epitomized by antecedents such as Count Alexandre de Marenches’s ‘Opération Moustique’ (see here: aljazeera.com/news/2003/4/24/war-with-drugs).”

I noticed c. 2003 that opiate addiction increased here in the U.S. heartland. Of course this time period corresponded to Washington’s invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. Was the U.S. invasion and destruction of Afghanistan the sole cause of America’s heroin problem? Obviously not. But I think it was one factor. Supply helps to create demand, that’s true of any commodity.

Commodification and Dehumanization

So you’re a supply-sider?! Even Reagan’s own supply-sider supreme, David Stockman, turned against the econ theory he was most responsible for creating.

Even more germane is the implied argument that the availability of drugs is what drives usage. A neat trick that assigns to individual personal consumer choice what is actually a huge systemic problem.

Why yes! People should chose to be born into well off families that live in areas with good schools and that nurture their kids instead of beating, raping, and psychologically abusing them. And why not send the economic losers to horrific and pointless wars? If you don’t understand how drugs function to relieve unbearable pain, read Dr. Gabor Mate’ on the realities of street addicts and Dr. Bessel van der Kolk on the PTSD of veterans.

All of which fits the structures of econ theory; since community devastation and ecological destruction aren’t part of corporate accounting they are dismissed as “externalities.” Which means they don’t count. We workers used to be personnel–you know, as if real people. Now we’re “human resources,” commodities like natural resources, things to be strip-mined and clear-cut, the valueless remains tossed aside.

I actually think we agree on some things but you sort of flew off on a tangent and kind of lost me.

I agree wholeheartedly that drugs can function to relieve unbearable pain and I think Aaron Mate’s father has done some fine work.