Missing records, billions in over-runs and flawed ships. reports on how the Australian Defence Department’s new BAE frigates project is a boondoggle for the British weapons-maker.

All smiles in 2018. Then Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne, BAE Systems Australia CEO Gabby Costigan, then Minister for Trade Simon Birmingham, then Liberal candidate Georgina Downer, former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, then Defence Minister Marise Payne, former Chief of Navy VADM Tim Barrett, Sen. David Fawcett and then South Australian Premier Steven Marshall seemed tickled pink at the BAE Systems Hunter-class frigates SEA 5000 announcement at the Osborne Shipyard in Adelaide. (Defence Department)

By Michelle Fahy

Declassified Australia

In a two-part investigation, Declassified Australia examines the flawed contracting process that led to a $46 billion naval ship-building deal that has been found to be suffering what an investigative audit described as “corruption vulnerabilities.”

In a two-part investigation, Declassified Australia examines the flawed contracting process that led to a $46 billion naval ship-building deal that has been found to be suffering what an investigative audit described as “corruption vulnerabilities.”

The company at the centre of the scandal, the U.K.’s arms giant, BAE Systems, is revealed to have lied to Australia’s Defence Department about the planned ship’s design.

Crucial departmental records of key decision-making meetings have gone missing, and no overall assessment of whether the selected BAE design was ever made.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) reported in May its findings on the multi-billion dollar contract Australia signed in December 2018 with BAE Systems to build nine Hunter-class frigates.

ANAO found that BAE had “over-stated” — bureaucrat language for lied — the level of development of the frigate’s design, which meant cost inflation and schedule slippage were severely under-estimated.

BAE exaggerated the “maturity” of its design to get around a key government objective requiring the ship to be based on an existing “military-off-the-shelf design” with “a minimum level of change.”

Defence selected the BAE Systems’ frigate even though the two other ships on its shortlist were considered “the two most viable designs.”

Business as Usual

Conflicts of interest, secret consulting deals and revolving door appointments, all undermine democracy, yet this is business as usual at the Defence Department, the nation’s biggest procurement agency.

Former senior BAE executives have been placed at the heart of Australia’s naval procurement. They have helped write government shipbuilding policy, have overseen the navy’s largest tenders and have even been hired by the government to negotiate on its behalf with their former employer on a deal now found to be riddled with probity concerns.

Granting preferential access to certain arms industry insiders escalated under previous Liberal-National Coalition governments and since 2022 has continued under the Albanese Labor government. So, this is also a story about state capture — when a corporation has the power to bend governments to its will.

When combined with departmental corruption or incompetence, or both, the result is Defence procurement projects that are billions of dollars over budget and running years late. As a result, the navy is facing massive capability gaps.

Whose Interests Served?

Australian Defence Department headquarters in Canberra. (Nick Dowling, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Defending the department’s decision not to assess the contract’s “value for money,” Defence told the audit office, “The government determined there to be value for money in establishing a sovereign, sustainable, cost-competitive continuous shipbuilding program in Australia.”

But the Australian Audit Office said Defence had “conflated” an objective of industry policy with the mandatory requirement of achieving “value for money” in procurement. The auditors said the Commonwealth procurement rules oblige departmental officials to assess value for money.

Interestingly, Defence did undertake value-for-money assessments on two other shipbuilding tenders it was running at the same time, both also under the nation’s Shipbuilding Plan — the Offshore Patrol Vessels and the Cape-class Patrol Boats.

Another mandatory requirement, a “whole-of-life cost” estimate for the frigates, was also not provided to government.

Within 24 hours of the ANAO report’s release, the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit had launched an urgent inquiry.

Auditor-General Grant Hehir criticised the program’s probity adviser, the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS), and the Finance Department, which oversees the procurement rules. At the committee’s first public hearing, on May 19, Hehir said that while the AGS had mentioned value for money to Defence it “drifted away pretty quickly” and “didn’t pursue the issue”:

“You’d expect people with responsibility for frameworks and issues like adhering to the law, which the procurement rules are, would hang on pretty tightly.”

Responding to criticism of its inability to produce key documents, the Defence Department countered that these numbered “less than 10,” and that more than 730,000 other documents were available. This remark was signed off by the two most senior Defence leaders in the country — Defence Secretary Greg Moriarty and the Chief of the Defence Force General Angus Campbell.

The auditor-general didn’t let their remark pass unnoticed at the parliamentary hearing. “Our concern is not just that all records should be kept but, particularly, important records should be kept,” he said. “In this case, [they] were significant records.”

The audit report noted Defence was a serial offender of deficient record-keeping. Perhaps its most pointed comment, however, was contained in a footnote quote from the commissioner for law enforcement integrity:

“Lack of record keeping can create corruption vulnerabilities within an Agency.”

Senior Audit Office official Tom Ioannou added: “We pursued this at length with Defence [giving] them every opportunity to provide the documented rationale [for shortlisting BAE].” The defence secretary was the decision-maker on the shortlisting of BAE.

Ioannou also said that minutes were unavailable of the Defence Committee meeting at which the decision to recommend BAE’s frigate was likely discussed. “This is an apex Defence enterprise level committee with well-established and elaborate secretariat arrangements … designed to capture exactly this sort of decision-making,” he said. This is the highest-level committee in Defence and includes the defence secretary and the chief of the Defence Force.

Suspicions exist of potential corruption in the multi-billion dollar contract. Possible “nefarious” conduct was suggested more than once by Committee chair Labor MP Julian Hill, while deputy chair, Liberal senator and former Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, referred to BAE Systems as a “very wily contractor.”

Faced with a multitude of questions they could not answer, officials said the department was conducting an internal investigation and would report back. The next hearing is likely to be in late July or August.

Over-Stated Design Maturity

One of the government’s five project objectives was that the frigate be based on a “military-off-the-shelf design” with “a minimum level of change,” but the shortlisting of BAE’s frigate was criticised for not meeting this criteria because it was still in the design phase and not yet in the water, unlike the other two shortlisted ships.

To counter this criticism, BAE Systems stated its design would be “de-risked” because the Australian program was running five years behind the U.K. program, meaning the Royal Navy would resolve design issues ahead of the Australian program.

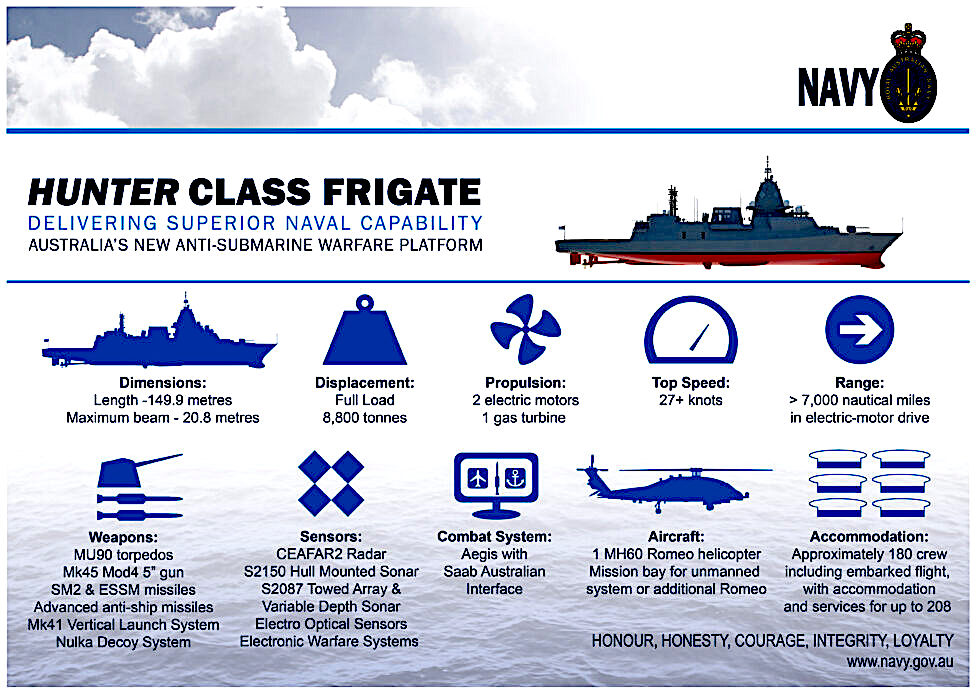

“A misguided emphasis on optimisation for anti- submarine warfare operations has resulted in Australia choosing a ship unsuited for its needs” — Former Navy Chief David Shackleton. (Infographic: Royal Australian Navy)

Despite those claims, the audit report found that the “immaturity” of the ship’s design was mostly to blame for mounting costs and schedule delays.

Australian taxpayers are paying BAE Systems more than $6 billion for the “design and productionisation” of the frigates.

Expressing consternation that BAE made the shortlist, Australia’s chief of navy from 1999-2002, former Vice Admiral David Shackleton, said, “Given the degree of redesign needed to progress to this point, it’s reasonable to question how [it] was placed on the list of contenders in the first place.”

As for the high design costs, Shackleton said some explanation was needed. In his 2022 48-page report he stated:

“How Australia found itself paying $6.26 billion to modify an existing design that was ostensibly mature enough for the U.K. to start construction, and… one that was proclaimed to be readily amenable to change, needs some explanation.”

Comparing costings across procurements is extremely difficult due to individualised modifications to suit a country’s requirements and the secrecy cloaking contractual arrangements. Yet the apparent magnitude of the difference between the Australian, Canadian and U.S. procurements is startling.

The Canadian navy is acquiring and modifying the same BAE frigate as Australia. Canada’s initial design modification contract was for CA$185 million ($205 million). Canada noted this amount would increase as the design evolved.

Shackleton told Declassified Australia that at face value the Canadian figure appears to be high, particularly when an advantage of the ship was purportedly its modern digital design, being ostensibly less difficult to modify than traditional methods normally involve.

This view is supported by a contract the U.S. Navy signed in 2018 with Italian shipbuilder Fincantieri to modify its frigate to suit U.S. needs, for US$15 million ($21 million). A U.S. Congressional Budget Office report said the U.S. frigate’s design costs could rise if design changes were made during construction.

The Defence Department is well known for excessive secrecy. It has not been transparent about the amount Australia is paying for the design modification.

Defence has said the $6 billion price tag for the Hunter-class frigate program’s “design and productionisation” covers three elements: design modifications, prototyping of ship blocks at the new Osborne shipyard and ordering “long-lead items for the first three ships.”

Declassified Australia asked Defence for a breakdown of the $6 billion and for more detail regarding the long-lead items. The department did not respond to our request.

BAE Frigate ‘Unsuited for Needs’

Former Navy Chief David Shackleton has called for the program to be scrapped and the funds redirected into acquiring ships that are more suitable.

His report found that:

“A misguided emphasis on optimisation for Anti Submarine Warfare operations has resulted in Australia choosing a ship unsuited for its needs.”

BAE Systems’ dockyard in Barrow-in-Furness, U.K. (Chris Allen, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Marcus Hellyer, a former senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, also listed similar concerns and alternative proposals. Hellyer noted:

“[BAE’s frigate] is under-gunned for the threat environment of the 2030s: its missile capacity is the most glaring shortfall… its 32 missile cells mean it’s taking a knife to a gunfight.”

The audit report said Defence was not even able to provide an estimate of the final cost of the frigates. It could say only that the cost was likely to be “significantly higher” than the $44.3 billion previously advised to government. This was already $10 billion more than the original $35 billion cost.

The cost blowouts are now so significant that the frigate program is “unaffordable” without cost cutting elsewhere or reducing the number of ships, according to Defence officials quoted in the audit report.

Defence Investigated BAE

The auditor’s report is not the first time questions have been raised about the nature of the relationship between the Australian Defence Department and BAE Systems.

In 2018 Defence commenced a secret investigation into BAE Systems over allegations that “Navy contracts have been inflated by tens of millions of dollars by being stuffed with unsubstantiated expenses.”

The “inflation” of BAE invoices by tens of millions of dollars allegedly occurred during its sustainment work on an earlier class of Australian frigates, the now-decommissioned Adelaide-class, under a contract awarded to BAE in 2008 without a competitive tender process.

Concerns about BAE’s invoicing had reportedly been first raised within Defence in 2014. However, Defence began its secret investigation four years later, in response to a whistleblower, but only after BAE had been awarded the Hunter-class frigate contract.

BAE was not alone in eliciting concerns over “corruption vulnerabilities.” Defence also investigated Thales Australia, its second largest weapons contractor, at the same time for invoicing irregularities on the same frigates.

An internal Defence audit found BAE’s Adelaide frigates contract had been reportedly “riddled with cost overruns, with the British company consistently invoicing questionable charges.”

So serious were the fraud allegations against BAE Systems they were escalated to Defence’s assistant secretary of fraud control, who referred several matters to the Independent Assurance Business Analysis and Reform Branch of the Defence Department.

When I asked Defence about the results of its secret investigations into BAE Systems, Defence Media responded that its investigation had found “no evidence” of inappropriate excess charges.

BAE’s Sordid Record

BAE Systems is Australia’s largest Defence contractor and the world’s sixth largest arms corporation. It has a sordid record of corruption globally as well as selling weapons to war crime abusers.

During the 1990s and 2000s, in “a deliberate choice that came from the top,” BAE Systems maintained an offshore shell company in the Cayman Islands called Red Diamond Trading that was used to channel hundreds of millions in bribes to key decision makers in a succession of arms deals.

The largest of these arms deals were the £43 billion ($82 billion) deals with Saudi Arabia known as Al Yamamah. An investigation by the U.K.’s Serious Fraud Office uncovered billions in “commission payments,” or bribes, paid by BAE Systems to members of the Saudi royal family and others, including for visits to the U.K. and foreign travel. The investigation was cancelled in 2006 by Prime Minister Tony Blair under pressure from BAE and the Saudis.

The Saudi War in Yemen has seen devastation and thousands killed, and over 4 million Yemenis fleeing their homes. But it has been good for business for BAE Systems.

BAE’s former chairman, Sir Roger Carr, was secretly recorded in 2019 making comments to shareholders on the war in Yemen.

“Civilians are killed in war. The solution is to stop wars at the earliest opportunity. And our belief is that if you supply first class equipment, you are the encouragement, particularly when used in defence, for people to stop fighting.”

BAE has certainly shown a unique way of ensuring business and ethics can co-exist.

Michelle Fahy is an independent writer and researcher, specialising in the examination of connections between the weapons industry and government, and has written in various independent publications. She is on twitter @FahyMichelle, and on Substack at UndueInfluence.substack.com. View all posts by Michelle Fahy

This article is from Declassified Australia.

Nothing surprising here. John Bull has always wanted Down Under to be undergunned and udder-rich !

Prime Minister Tony Blair once personally intervened to stop an investigation into possible corruption at BAE.

If there had been nothing in the allegations, then it would have made sense to let the inquiry go ahead.

This can reasonably described as obstruction of justice.

Any Australian who had a lingering hope that a Labor Government would be an improvement on their Liberal predecessors has surely been disillusioned since Albo took the helm- they are just as dodgy, as beholden to the US, as bad on global warming, as useless with respect to Julian Assange, equally ready to destroy relations with China, and they have little to no interest in improving the lot of Australian citizens.

Sounds as if Australia’s and the U.K.’s political and administrative processes are about as corrupt as the U.S.’s are, but that their watchdogs nominally responsible for overseeing these processes may be somewhat more diligent in doing so though perhaps similarly impotent to correct matters.

Being rotten to the core is hardly the best advertisement for attracting support from other countries which are not equally rotten.

Well said. Tom Paine warned about the rot of war profiteers back in 1791.

hxxps://war**profiteer**story.blogspot.com

[Please remove asterisks and replace xx with tt to use link.]