As the U.S. pushes for a major power conflict in the Asia-Pacific, it is essential to develop lines of communication and build understanding among China, the West and the developing world, writes Vijay Prashad.

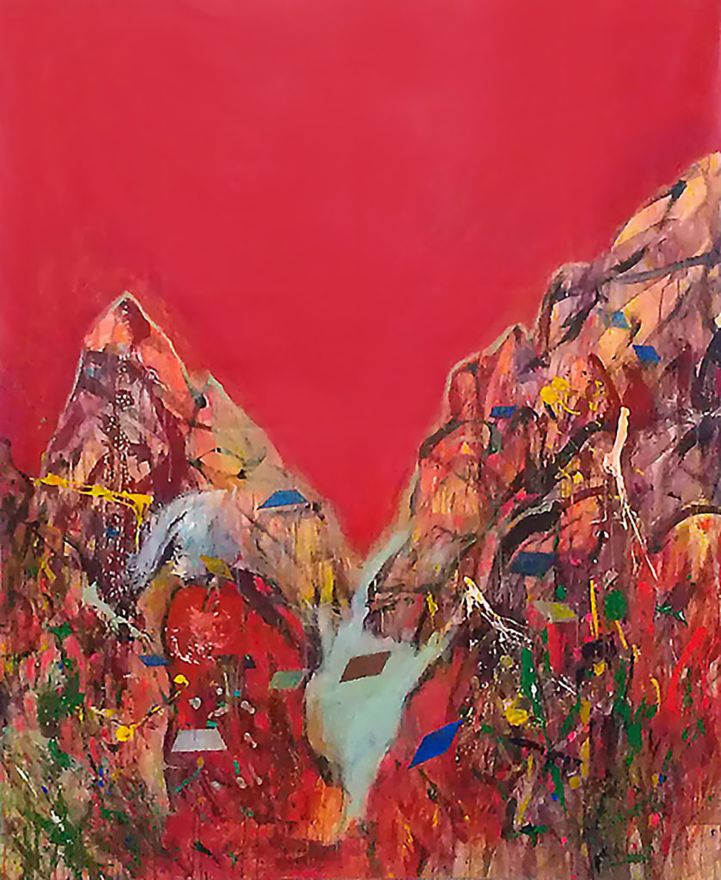

Xiong Wenyun, China, “Moving Rainbow,” 1998–2001.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

On March 20, China’s President Xi Jinping and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin spent over four hours in private conversation. According to official statements after the meeting, the two leaders talked about the increasing economic and strategic partnership between China and Russia — including building the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline — and the Chinese peace initiative for the war in Ukraine.

On March 20, China’s President Xi Jinping and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin spent over four hours in private conversation. According to official statements after the meeting, the two leaders talked about the increasing economic and strategic partnership between China and Russia — including building the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline — and the Chinese peace initiative for the war in Ukraine.

Putin said that “many of the provisions of the peace plan put forward by China are consonant with Russian approaches and can be taken as the basis for a peaceful settlement when the West and Kiev are ready for it.”

These steps towards peace have not received a warm welcome in Washington. Ahead of Xi’s visit to Moscow, John Kirby, the spokesperson for the U.S. National Security Council, declared that any “call for a ceasefire” in Ukraine by China and Russia would be “unacceptable.”

As details of the meeting emerged, U.S. officials reportedly expressed fear that the world might embrace China and Russia’s efforts to secure a peaceful resolution and end the war. The Atlantic powers are, in fact, redoubling their efforts to prolong the conflict.

On the day of the meeting between Xi and Putin, the United Kingdom’s minister of state at the Ministry of Defence, Baroness Annabel Goldie, told the House of Lords that “[a]longside our granting of a squadron of Challenger 2 main battle tanks to Ukraine, we will be providing ammunition including armour-piercing rounds which contain depleted uranium.”

Goldie’s statement came on the 20th anniversary of the U.S.-U.K. invasion of Iraq, in which the West used depleted uranium on the Iraqi population to deleterious effect. In reference to the U.K.’s provision of depleted uranium to Ukrainian forces, Putin said that “it seems that the West really has decided to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian — no longer in words, but in deeds.” In response, Putin said that Russia would deploy tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus.

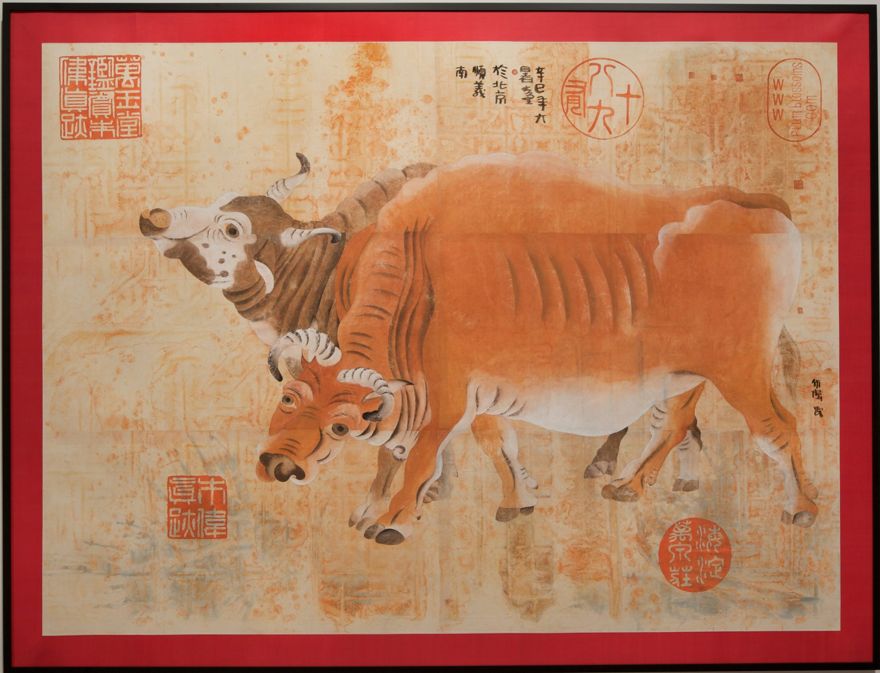

Liu Xiaodong, China, “East,” 2012.

Within China, Xi’s visit to Russia was widely discussed with a general sense of pride that China’s government is taking leadership both to block the ambitions of the West and to seek peace in the conflict. These discussions, reflected in journals and on social media platforms such as WeChat, Douyin, Weibo, LittleRedBook, Bilibili and Zhihu, emphasised how China, a developing country, has nonetheless been able to overcome its limitations and take on a leadership position in the world.

These discussions within China are largely unavailable to people outside the country for at least three reasons: first, they take place in Chinese and are not often translated into other languages; second, they take place on social media platforms that, in addition to being in Chinese, are not used by people from outside the Chinese-speaking community; and third, growing Sinophobia, stemming from a longstanding colonial history of thought and exacerbated by the New Cold War, has deepened a disregard for discussions in China that do not adopt the Western worldview.

For these reasons, and more, there is a genuine lack of understanding about the range of opinions in China concerning the shifts in the world order and the country’s role in these shifts.

Within China, there is a rich tradition of intellectual debate that takes place in journals inspired in one way or another by Chen Duxiu’s New Youth, first published in 1915. In the first issue of that journal, Chen (1879–1942), who was a founding member of the Communist Party of China, published a letter to the youth which included a list of admonitions that seems to have set the terms for the intellectual agenda of the next hundred years:

Be independent and not enslaved

Be progressive and not conservative

Be in the forefront and not lagging behind

Be internationalist and not isolationist

Be practical and not rhetorical

Be scientific and not superstitious

The experience of New Youth set in motion journal after journal, each with an agenda to build more adequate theories about developments in China that seek to establish the country’s sovereignty and lift them out of the so-called century of humiliation, a period that was characterised by Western and Japanese imperialist intervention.

In 2008, several leading intellectuals in the country founded a journal, Wenhua Zongheng, which has increasingly become a platform to debate what Xi called the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” The bi-monthly journal features the country’s leading voices, who offer various perspectives on important issues of the day such as the state of the post-Covid-19 world and the importance of rural revitalisation.

Last year, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and Dongsheng began a conversation with the editors of Wenhua Zongheng which led to the production of a quarterly international edition of the journal. Through this partnership, select essays from the Chinese editions of the journal are translated into English, Portuguese and Spanish, and an additional column is featured in the Chinese edition that brings voices from Africa, Asia and Latin America into dialogue with China. The first issue of this international edition (Vol. 1, No. 1) was launched this week, with the theme “On the Threshold of a New International Order.”

This issue features three essays by leading scholars in China — Yang Ping (editor of Wenhua Zongheng), Yao Zhongqiu (professor at the School of International Studies and dean of the Centre for Historical Political Studies, Renmin University of China) and Cheng Yawen (dean of the Department of Political Science at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Shanghai International Studies University), as well as my brief editorial.

Both Professors Yao and Cheng discuss the changes in the current international order, mainly the decline of U.S. unipolarity and the emergence of regionalism.

Professor Yao’s contribution, which goes back to the Ming dynasty (1388–1644), makes the case that the changes taking place today are not necessarily the creation of a new order, but the return of a more balanced world system as China “revives” its place in the world and as the ambitions of the U.S. find their limits in the emergence of key countries in developing countries, including China, India and Brazil.

Zhou Chunya, China, “New Generation Tibetan,” 1980.

All three essays focus on the importance of China’s role in the developing world, both in economic terms (such as through the 10-year-old Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI) and in political terms (such as through China’s attempt to restart a peace process in Ukraine).

Editor Yang Ping is firm in his view that “China’s historical destiny is to stand with the Third World,” both because — despite its major advances — China remains a developing country and because China’s insistence upon multilateralism, as Professor Cheng argues, means that it does not seek to displace the U.S. and become a new global hegemon.

Yang ends his account with three considerations: first, that China must not be led merely by commercial interests but must “prioritise what is necessary to ensure strategic survival and national development;” second, that China must intervene in debates about the new international system by introducing the BRI’s principles of “consultation, contribution and shared benefits,” which include seeking to expand the zone of peace against the habits of war; and third, that China must encourage the creation of an institutional mechanism beyond economic cooperation — such as a “Development International” — to promote the genuine sovereignty of nations, the dignity of peoples faced with the International Monetary Fund’s debt-austerity trap and a new internationalism.

Zhu Wei, China, “China Diary,” No. 52, 2001.

The perspectives of Yang, Yao and Chen are essential reading as part of an important initiative for global dialogue. The second edition of Wenhua Zongheng will focus on China’s path to modernisation.

As the United States pushes for a major power conflict in the Asia-Pacific, it is essential to develop lines of communication and build bridges towards mutual understanding between China, the West and the developing world. As I wrote in the closing words of my editorial, “[i]nstead of the global division pursued by the New Cold War, our mission is to learn from each other towards a world of collaboration rather than confrontation.”

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Where is the climate lens? How is another pipeline helpful? How is bolstering unsustainable global trade responding to the immediate emergency? No nation state should take priority over the incredible variety of individual necessities.

I have subscribed to it. A refreshing revelation after living in the bubble of western propaganda.

That isn’t going to happen. Russia is not weak. The east and global south are changing the world and it is the U.S. that is weak and isolated. And about time, too.

The hegemonical warlike tribe south of the Canadian border has a front row seat cheering for the continuation of murder and mayhem in the Ukraine. Hoping the while that the Russians will be so weakened that they will no longer be a threat to NATO and its plans for world domination.

Your explanations and beautiful illustrations to so many articles are always welcome, Vijay. Thank you.

The key to Prashad’s article is his revealing of the TriContinental institute and Wenhua Zongheng’s collaboration. Having read the first issue, I cannot recommend it enough.

The only lines of communication the US understands is when the communication lines pass through the US.

Imagine the world now if the Ming hadn’t shut down Zheng He’s great trading expeditions around the world. The “opening up” of the world then, and in that way, would have strongly restricted Iberian, English, Dutch and French efforts to colonise the world outside of Europe. China is not now going to repeat the blindness of the later Ming.

Thank you for this report. We certainly are not getting it from our MSM who are sppreading the Propaganda that our war-mongering government instructs them to publish.

It is essential, if we are to live in a world worth surviving, that we at least hear other perspectives in terms not couched in pejoratives. Understand what others mean and not the distortion of their perspectives which we are constantly fed. Nicely done!!! Congratulations.

It’s a pretty simple choice for Citizens of the World?

China offers Peace, Order & Friendship & Stability, zero interference in Political affairs, assists with Business development & Trade deals & provides Infrastructure via the BRI, Ports, Roads & Railways etc & a environment where developing Nations can rise!

America, offers no Peace but never ending Wars, zero Friendship only Vassalage, interference & meddling in other Nations Political affairs, zero sum game Trade deals, debt slavery via US Institutions like the IMF & World Bank, instability, Regime change, conflict & chaos, looting & resources theft & no assistance to build infrastructure while offering nothing to help developing Nations rise up but purposely does everything to ensure they remain impoverished & poor!

It’s a no brainer isn’t it? Who would you pick? Well the answer is obvious, the World outside of the West is gravitating daily towards China & Russia & a World outside of the USD Petrodollar system, everyone has had enough of America, it’s Wars, it’s chaos, it’s bullying, it’s threats & coercion & its deathcult “Rules based World Order”! Everyone is moving towards Russia & China’s Fair World Order, this Multipolar ecosystem that is leaving the decaying US Empire & it’s declining Hegemony in the rear view mirror & driving towards a more prosperous & equitable Future without this arrogant, ignorant Nation making up the Road rules that the entire World must follow! It’s GAME OVER & the sooner America deals with this reality, the better, but this won’t end well because this US Nation is so vile & vindictive that they would rather burn everything to the ground rather than allow the rise of other World powers, it’s the mentality of, if we can’t rule, no one else will rule? God help us all!

Very likely internal confilcts between rich and poor will make the US weaker and weaker abroad. The current situation just is not stable.

Excellent. The foundation for peace is always dialogue and efforts to understand one another as full human beings. At this point in time, the US has simply lost the thread to where American officials are worried most of all that peace may break out. Consider that for a moment and weep.