Regarding astropolitics, the authors note that by the time Beijing was able to contribute to the International Space Station, U.S. Congress had prevented it from doing so.

Three taikonauts rode aboard the Shenzhou 15 mission on their way to China’s new Tiangong space station. (Xinhua News Agency via Getty Images)

By Eytan Tepper and Scott Shackelford

The Conversation

The International Space Station is no longer the only place where humans can live in orbit.

The International Space Station is no longer the only place where humans can live in orbit.

On Nov. 29, the Shenzhou 15 mission launched from China’s Gobi Desert carrying three taikonauts – the Chinese word for astronauts.

Six hours later, they reached their destination, China’s recently completed space station, called Tiangong, which means “heavenly palace” in Mandarin. The three taikonauts replaced the existing crew that helped wrap up construction.

With this successful mission, China has become just the third nation to operate a permanent space station.

China’s space station is an achievement that solidifies the country’s position alongside the U.S. and Russia as one of the world’s top three space powers. As scholars of space law and space policy who lead the Indiana University Ostrom Workshop’s Space Governance Program, we have been following the development of the Chinese space station with interest.

Unlike the collaborative, U.S.-led International Space Station, Tiangong is entirely built and run by China. The successful opening of the station is the beginning of some exciting science. But the station also highlights the country’s policy of self-reliance and is an important step for China toward achieving larger space ambitions among a changing landscape of power dynamics in space.

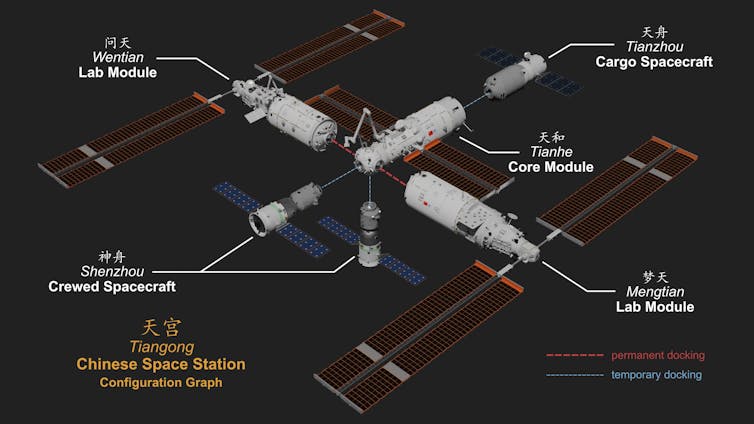

The Tiangong space station is much smaller than the International Space Station and consists of three modules. (Shujianyang/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

Capabilities of a Chinese Station

The Tiangong space station is the culmination of three decades of work on the Chinese manned space program. The station is 180 feet (55 meters) long and is comprised of three modules that were launched separately and connected in space.

These include one core module where a maximum of six taikonauts can live and two experiment modules for a total of 3,884 cubic feet (110 cubic meters) of space, about one-fifth the size of the International Space Station. The station also has an external robotic arm, which can support activities and experiments outside the station, and three docking ports for resupply vehicles and manned spacecraft.

Like China’s aircraft carriers and other spacecraft, Tiangong is based on a Soviet-era design – it is pretty much a copy of the Soviet Mir space station from the 1980s. But the Tiangong station has been heavily modernized and improved.

The Chinese space station is slated to stay in orbit for 15 years, with plans to send two six-month crewed missions and two cargo missions to it annually. The science experiments have already begun, with a planned study involving monkey reproduction commencing in the station’s biological test cabinets. Whether the monkeys will cooperate is an entirely different matter.

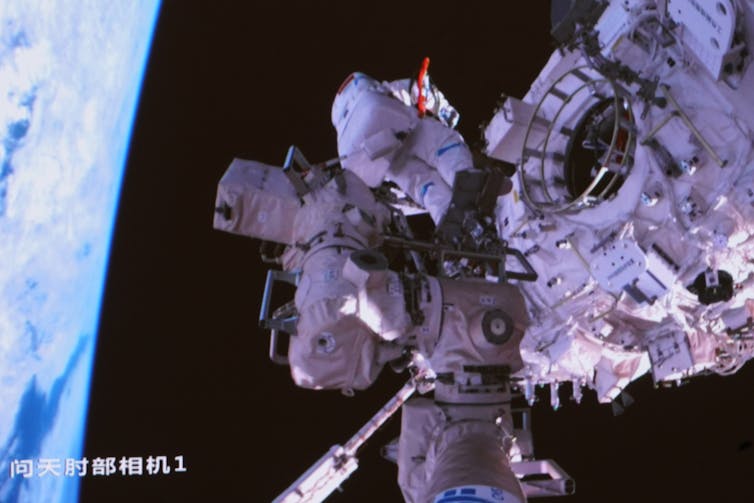

This image from a video feed at the Beijing Aerospace Center on Nov. 17, shows taikonauts working on the Tiangong station. (Xinhua News Agency via Getty Images)

Science & a Steppingstone

The main function of the Tiangong station is to perform research on life in space. There is a particular focus on learning about the growth and development of different types of plants, animals and microorganisms, and there are more than 1,000 experiments planned for the next 10 years.

Tiangong is strictly Chinese made and managed, but China has an open invitation for other nations to collaborate on experiments aboard Tiangong. So far, nine projects from 17 countries have been selected.

Although the new station is small compared to the 16 modules of the International Space Station, Tiangong and the science done aboard will help support China’s future space missions.

Support CN’s Winter Fund Drive!

In December 2023, China is planning to launch a new space telescope called Xuntian. This telescope will map stars and supermassive black holes among other projects with a resolution about the same as the Hubble Space Telescope but with a wider view. The telescope will periodically dock with the station for maintenance.

China also has plans to launch multiple missions to Mars and nearby comets and asteroids with the goal of bringing samples back to Earth. And perhaps most notably, China has announced plans to build a joint Moon base with Russia – though no timeline for this mission has been set.

The three-person crew of taikonauts greets the crew already aboard the Tiangong station in early December.

Astropolitics

A new era in space is unfolding. The Tiangong station is beginning its life just as the International Space Station, after more than 30 years in orbit, is set to be decommissioned by 2030.

The International Space Station is the classic example of collaborative ideals in space – even at the height of the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union came together to develop and launch the beginnings of the space station in the early 1990s. By comparison, China and the U.S. have not been so jovial in their orbital dealings.

In the 1990s, when China was still launching U.S. satellites into orbit, concerns emerged that China was accidentally acquiring – or stealing – U.S. technology. These concern in part led to the Wolf Amendment, passed by Congress in 2011, which prohibits NASA from collaborating with China in any capacity.

China’s space program was not mature enough to be part of the construction of the International Space Station in the 1990s and early 2000s. By the time China had the ability to contribute to the International Space Station, the Wolf Amendment prevented it from doing so.

It remains to be seen how the map of space collaboration will change in the coming years. The U.S.-led Artemis Program that aims to build a self-sustaining habitat on the Moon is open to all nations, and 19 countries have joined as partners so far.

China has also recently opened its joint Moon mission with Russia to other nations. This was partly driven by cooling Chinese-Russian relations but also due to the fact that because of the war in Ukraine, Sweden, France and the European Space Agency canceled planned missions with Russia.

As tensions on Earth rise between China, Russia and the West, and some of that jockeying spills over into space, it remains to be seen how the decommissioning of the International Space Station and operation of the Tiangong station will influence the China-U.S. relationship.

An event like the famous handshake between U.S. astronauts and Russian cosmonauts while orbiting Earth in 1975 is a long way off, but collaboration between the U.S. and China could do much to cool tensions on and above the Earth.![]()

Eytan Tepper is visiting assistant professor of space governance at Indiana University and Scott Shackelford is professor of business law and ethics at Indiana University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!

Donate securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

No reason to expect US Elites & Privatised space Attempts to include: China… Russia… Or US Public Itself in upcoming Space Resource Rivalry…

Although present Political Patterns May Imply NASA Co-Operation W the Bezos’s, Musks, or Similar Corporate Others!

I have to laugh. The heart of the ISS is Russian, and most of the rest is derived from Russian technology. The Russians have also shared much of their space technology with China; that is what gave the Chinese program its head start. There was very little of purely U.S. technology for the Chinese to ‘copy or steal’.

Meaning, that as usual, the U.S. has gone and cut off its nose to spite its face, and specifically in regards to cooperation in space with the Chinese. And I don’t forsee much more cooperation with Russia, either. The Russians will do their duty and fulfill their obligations to the ISS, and then that will be it. Then, watch the Chinese and Russians leave the U.S. in the dust…

Another step towards a multi-polar world, and further fading of US hegemony.

Great to see Tiangong and China’s space program mentioned here, but there’s a fair bit of misinformation in this article. It’s ridiculous to suggest that Tiangong is simply a copy of Mir. If you take a look at David S.F. Portree’s excellent site “No Shortage of Dreams” you’ll see numerous US proposals for mid-sized space stations that resemble Tiangong. And while it may be smaller than the ISS at the moment, China built backups for all 3 Tiangong modules in case of a launch failure that they are now considering launching to double the size of the station.

It was US obstructionism that prevented China’s participation in the ISS, not technical immaturity. China’s space program was certainly mature enough to support the ISS from the late ’90s onward, especially compared with ISS partners Japan and Canada. The ‘Shenzhou’ crewed spacecraft first flew in 1999 and sent the first Taikonaut to orbit in 2003. This schedule could easily have been accelerated, with unscrewed Shenzhous carrying cargo to the ISS in the late ’90s (as the uncrewed Soyuz variant ‘Progress’ has done throughout the station’s history) following by crewed flights in the 2000s. The reason this did not occur is entirely due to US obstructionism.

The US sought to undermine the Chinese space program in order to prevent a rival from challenging the West’s monopoly on space launch services and spy satellites. After the dissolution of the USSR its space program could no longer support adequate reconnaissance from space and its major space enterprises were forced into joint ventures with US companies to enter the global space launch market. China on the other hand was developing a new generation of reconnaissance satellites and possessed a stable of launch vehicles (the Long March 2E and Long March 3 series) that were very competitive with western launchers. As the Long March rockets began to dominate the launch market, the US began to use its usual bag of tricks to hold China back, from sanctions to outright sabotage of several high profile Long March 2E flights.

The so-called Artemis Accords are the epitome of the ‘International Rules Based Order’ in that the US makes the rules then issues the orders. There was never any consideration of including China or Russia, only vassals need apply. The aim of the Accords is to supplant the Outer Space Treaty and allow the US to carve out a ‘sphere of influence’ on the Moon. China and Russia put forward the ILRS in response (which really is open to all) and are accelerating their lunar programs to prevent the extension of the US empire to the Moon.

China has been developing its Long March 9 rocket for lunar missions but it is now undergoing a redesign to allow reusablity in the event that SpaceX’s ‘Starship’ is successful. In its place China will use an advanced derivative of the Long March 5 that launched Tiangong. Two Long March 5G’s will launch a crewed spacecraft and lunar lander separately to the moon where they will dock and carry out a landing in the late 2020’s. The US is planning to return to the moon by 2025, although this will require SpaceX’s Starship to work as advertised and launch numerous times over a short period, alongside the SLS/Orion system that finally completed its first mission recently which should have taken place in 2016! In comparison, China is well set up to resist US plans to extend its empire beyond the earth.

You are spot on in your concise yet circumspect comments. Absolutely right, as an extension of its rather overt agenda to prevent ANY potential rival from upstaging the US even on Earth, the US pro-actively moved to create legal obstacle via the Wolf Amendment to restrain rivals in space too. This keeps to the long US techno-tradition of cold-shouldering the French on Concorde in the past and again the French via AUKUS in recent times. The Chinese are good learners from the experiences of even others not to mention their direct samplings of Anglo-Saxon intrigues along their littorals and via their “security” pivoting to Asia. They are also quite cautious to the privatized space trappings promoted and collaborations offered by American billionaires to which the Russians sometimes succumb to ! So, it is quite doubtful if the Chinese would easily welcome Americans into their Tiangong whenever the ISS is decommissioned despite their open invitation to all nations.

I hope space research replaces war-war-war in US priorities!

The US has not been playing nice with Russia in space for a long time now – since well before the whole US/EU fomented coup in 2014.

The US doesn’t play nice with most countries – including its so-called friends & allies!