Murray recommends a spell there to any other middle-class person who, like himself, was foolish enough to believe that Scotland is a socially progressive country.

H.M. Prison Edinburgh. (Kim Traynor, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Craig Murray

CraigMurray.org.uk

In my second week in Saughton jail, a prisoner pushed open the door of my cell and entered during the half hour period when we were unlocked to shower and use the hall telephone in the morning. I very much disliked the intrusion, and there was something in the attitude of the man which annoyed me —wheedling would perhaps be the best description. He asked if I had a Bible I could lend him. Anxious to get him out of my cell, I replied no, I did not. He shuffled off.

In my second week in Saughton jail, a prisoner pushed open the door of my cell and entered during the half hour period when we were unlocked to shower and use the hall telephone in the morning. I very much disliked the intrusion, and there was something in the attitude of the man which annoyed me —wheedling would perhaps be the best description. He asked if I had a Bible I could lend him. Anxious to get him out of my cell, I replied no, I did not. He shuffled off.

I immediately started to feel pangs of guilt. I did in fact have a Bible, which the chaplain had given me. It was, I worried, a very bad thing to deny religious solace to a man in prison, and I really had no right to act the way I did, based on an irrational distrust. I went off to take a shower, and on the way back to my cell was again accosted by the man.

“If you don’t have a Bible,” he said, “Do you have any other book with thin pages?”

He wanted the paper either to smoke drugs, or more likely to make tabs from a boiled-up solution of a drug.

You cannot separate the catastrophic failure of the Scottish penal system — Scotland has the highest jail population per capita in all of Western Europe –- from the catastrophic failure of drugs policy in Scotland.

Ninety percent of the scores of prisoners I met and spoke with had serious addiction problems. Every one of those was a repeat offender, back in jail, frequently for the sixth, seventh or eighth time. How addiction had led them to jail varied. They stole, often burgled, to feed their addiction. They dealt drugs in order to pay for their own use. They had been involved in violence — frequently domestic — while under the influence.

I had arrived in Saughton jail on Sunday, Aug. 1. After being “seen off” by a crowd of about 80 supporters outside St Leonards Police Station, I had handed myself in there at 11 a.m., as ordered by the court.

A tearful farewell to Craig Murray with his supporters singing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ as he hands himself in to the police at St Leonards Police Station, Edinburgh to begin his 8 month sentence for reporting on the Alex Salmond case. Journalism under threat in Scotland and the UK. pic.twitter.com/X38Rf8opwA

— Ragged Trousered Philanderer (@RaggedTP) August 1, 2021

The police were expecting me, and had conducted me to a holding area, where my possessions were searched and I was respectfully patted down. The police were very polite. I had been expecting to spend the night in a cell at St Leonards and to be taken to jail in a prison van on the Monday morning. This is what both my lawyers and a number of policemen had explained would happen.

In fact, I was only half an hour in St Leonards before being put in a police car and taken to Saughton. This was pretty well unique – the police do not conduct people to prison in Scotland. At no stage was I manacled or handled and the police officers were very friendly. Reception at Saughton prison – where prisoners are not usually admitted on a Sunday – were also very polite, even courteous. None of this is what happens to an ordinary prisoner, and gives the lie to the Scottish government’s claim that I was treated as one.

[Background: Craig Murray Is a Free Man]

I was not fingerprinted either in the police station or the jail, on the grounds I was a civil prisoner with no criminal conviction. At reception my overcoat and my electric toothbrush were taken from me, but my other clothing, notebook and book were left with me.

I was then taken to a side office to see a nurse. She asked me to list my medical conditions, which I did, including pulmonary hypertension, anti-phospholipid syndrome, Barrett’s oesophagus, atrial fibrillation, hiatus hernia, dysarthria and a few more. As she typed them in to her computer, options appeared on a dropdown menu for her to select the right one. It was plain to me she had no knowledge of several of these conditions, and certainly no idea how to spell them

The nurse cut me off very bluntly when I politely asked her a question about the management of my heart and blood conditions while in prison, saying someone would be round to see me in the morning. She then took away from me all the prescription medications I had brought with me, saying new ones would be issued by the prison medical services. She also took my pulse oximeter, saying the prison would not permit it, as it had batteries. I said it had been given to me by my consultant cardiologist, but she insisted it was against prison regulations.

This was the most disconcerting encounter so far. I was then walked by three prison officers along an extraordinarily long corridor – hundreds of yards long – with the odd side turning, which we ignored. At the end of the corridor, we reached Glenesk Block. The journey to my cell involved unlocking eight different doors and gates, including my cell door, every one of which was locked behind me. There was no doubt that this was very high security detention.

12 Feet by 8 Feet

Once I reached floor 3 of Glenesk Block, which houses the admissions wing, we acquired two further guards from the landing, so five people saw me into my cell. This was 12 feet by 8 feet.

May I suggest that you measure that out in your room? That was to be my world for the next four months. In fact, I was to spend 95 percent of the next four months confined in that space.

The door was hard against one wall, leaving space within the 12 feet by 8 feet cell for a 4 feet by 4 feet toilet in one corner next to the door. This was fully walled in, to the ceiling, and closed properly with an internal door. This little room contained a toilet and sink. The toilet had no seat. This was not an accident – I was not permitted a toilet seat, even if I provided it myself. It was a normal U.K.-style toilet, designed to be used with a seat, with the two holes for the seat fixing, and a narrow porcelain rim.

The toilet was filthy. Below the waterline it was stained deep black with odd lumps and ridges. Above the waterline it was streaked and spotted with excrement, as was the rim. The toilet floor was in a disgusting state. The cell itself was dirty with — everywhere a wall or bolted-down furniture met the floor — a ridge built up of hardened black dirt.

Support CN’s Winter Fund Drive!

A female guard looked around the cell, then came back to give me rubber gloves, a surface cleaner spray and some cloths. So, I spent my first few hours in my cell on my knees, scrubbing away furiously with these inadequate materials.

The female guard had advised me that even after cleaning the cell I should always keep shoes on, because of the mice. I heard them most nights in my cell, but never saw one. The prisoners universally claim them to be rats, but not having seen one I cannot say.

A guard later explained to me that prisoners are responsible for cleaning their own cells, but as nobody generally stayed in a new admissions cell for more than two or three nights, nobody bothered. Cells for new arrivals will be cleaned out by a prisoner work detail, but as I had arrived on a Sunday, that had not happened.

So about 3 p.m. I was locked in the cell. At 5.20 p.m. the door opened for two seconds to check I was still there, but that was it for the day. There I was confused, disoriented and struggling to take in that all this was really happening. I should describe the rest of the cell.

A narrow bed ran down one wall. I came to realize that prison in Scotland still includes an element of corporal punishment, in that the prisoner is very deliberately made physically uncomfortable. Not having a toilet seat is part of this, and so is the bed. It consists of an iron frame bolted to the floor and holding up a flat steel plate, completely un-sprung. On this unyielding steel surface there is a mattress consisting simply of two inches of low-grade foam – think cheap bath sponge – encased in a shiny red plastic cover slashed or burnt through in several places and with the colour worn off down the centre.

“A narrow bed ran down one wall. I came to realize that prison in Scotland still includes an element of corporal punishment, in that the prisoner is very deliberately made physically uncomfortable.”

The mattress was stamped with the date 2013 and had lost its structural resistance, to the extent that, if I pinched it between my finger and thumb, I could compress it down to a millimetre. On the steel plate, this mattress had almost no effect and I woke up after a sleepless first night with acute pain throughout my muscles and difficulty walking. To repeat, this is deliberate corporal punishment – a massively superior mattress could be provided for about £30 more per prisoner, while in no way being luxurious. The beds and mattresses can only be designed to inflict both pain and, perhaps more important, humiliation. It is plainly quite deliberate policy.

It is emblematic of the extraordinary lack of intellectual consistency in the Scottish prisons system that cells are equipped with these Victorian punishment beds but also with TV sets showing 23 channels including two Sky subscription channels (of which I shall write more in another instalment). The bed is fixed along one long wall, while a 12-inch plywood shelf runs the length of the other and can serve as a desk.

At one end, up against the wall of the toilet, this desk meets a built-in plywood shelving unit fixed into the floor, on top of which are sat the television and kettle next to two power points. At the other end of the desk, a further set of shelves are attached to the wall above. There is a plastic stackable chair of the cheapest kind – the sort you see stacked outside poundshops as garden furniture.

On the outside wall there is a small double-glazed window with heavy, square iron bars two inches thick running both horizontally and vertically, like a noughts and crosses grid. The window does not open, but had metal ventilation strips down each side, which were stuck firmly closed with black grime. At the other end of the cell, next to the toilet, the heavy steel door is hinged so as to have a distinct gap all round between the door and the steel frame, like a toilet cubicle door.

Above the desk shelf is fixed a noticeboard, which is the only place prisoners are allowed to put up posters or photos. However, as prisoners are not permitted drawing pins, staples, sellotape or blu tak, this was not possible. I asked advice from the guards who suggested I try toothpaste. I did – it didn’t work.

There is a single neon light tube.

Massive Overcrowding

Apartment block in Muirhouse, one of the places in Edinburgh that is “heard over and over” inside the prison. (Ian S, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The admissions unit has single-occupancy cells, of which there are very few in the rest of the jail. All the prison’s cells were designed for single occupancy, but massive overcrowding means that they are mostly in practice identical to this description, but with a bunk bed rather than a single bed.

The prison is divided into a number of blocks. Glenesk block had three floors, each containing 44 of these cells. Each floor is entered by a central staircase and has a centrally located desk where the guards are stationed. Either side of the desk are two heavy metal grills stretching right across the floor and dividing it into two wings. Within the central area is the kitchen where meals are collected (though not prepared), then eaten back locked in the cell.

The corridor between the cells either side of each wing is about 30 feet wide. It contains a pool table and fixed chairs and tables, and is conceived as a recreational area. There are two telephones at the end of each wing from which prisoners may call (at 10p a minute) numbers from a list they have pre-registered for approval.

The various cell blocks are located off that central spine corridor whose length astonished me at first admission. I did not realise then that this is a discreet building in itself rather than a corridor inside a building – it is like a long concrete overground tunnel.

I should describe my typical day the first ten weeks. At 7.30 a.m. the cell door springs open without warning as guards do a head count. The door is immediately locked again. At 8 a.m. cereals, milk and morning rolls are handed in, and the door is immediately locked again. At 10 a.m. I was released into the corridor for 30 minutes to shower and use the telephone. The showers are in an open room but with individual cubicles, contrary to prison movie cliche. At 10.30 a.m. I was locked in again.

At 11 a.m. I was released for one hour and escorted under supervision to plod around an enclosed, tarmac exercise yard about 40 paces by 20 paces. This yard is filthy and contains prison bins. One wing of Glenesk block forms one side, and the central spine corridor forms another; the wall of a branch corridor leading to another cell block forms a third and a fence dividing off that block a fourth. The walls are about 10 feet high and the fence about 16 feet high.

In the non-admissions, larger area of Glenesk block the cells had windows with opening narrow side panels. It is the culture of the prison that rather than keep rubbish in their cells and empty it out at shower time, the prisoners throw all rubbish out of their cell windows into the exercise yard. This includes food waste and plates, newspapers, used tissues and worse. At meal times, sundry items (bread, margarine, etc.) are available on a table outside the kitchen and some prisoners scoop up quantities simply to throw them out of the window into the yard.

“It is the culture of the prison that rather than keep rubbish in their cells and empty it out at shower time, the prisoners throw all rubbish out of their cell windows into the exercise yard.”

I believe the origin of this is that this enclosed yard is used by protected prisoners, many of whom are sexual offenders. Glenesk house has a protected prisoner area on its second floor. “Mainstream” prisoners from Glenesk exercise on the astroturf five-a-side football pitch the other side of the spine corridor. (For four months that pitch was the view from my window and I never saw a game of football played. After three months the goals were removed.) New admissions exercise in the protected yard because they have not been sorted yet – that sorting is the purpose of the new admissions wing. New prisoners therefore have to plough through the filth prepared for protected prisoners.

At times large parts of this already small exercise yard were ankle deep in dross – it was cleaned out intermittently, probably on average every three weeks. Only on a couple of occasions was it so bad I decided against exercise. After exercise getting the sludge off my shoes as we went straight back to my cell was a concern. I now understood how the cell had got so dirty.

After exercise, at noon I collected my lunch and was locked back in the cell. Apart from two minutes to collect my tea, I would be locked in from noon until 10 a.m. the following morning, for 22 hours solid, every single day. In total I was locked in for 22-and-a-half hours a day for the first 10 weeks. After that I was locked in my cell for 23 hours and 15 minutes a day due to a Covid outbreak.

At 5 p.m. the door would open for a final headcount, and then we would be on lockdown for the night, though in truth we had been locked down all day. Lockdown here meant the guards were going home.

Now I want you again to just mark out 12 feet by 8 feet on your floor and put yourself inside it. Then imagine being confined inside that space a minimum of 22-and-a-half hours a day. For four months. These conditions were not peculiar to me – it is how all prisoners were living and are still living today. The library, gym and all educational activities had been closed “because of Covid.” The resulting conditions are inhumane – few people would keep a dog like that.

It is also worth noting that Covid is an excuse. In September 2017 an official inspection report already noted that significant numbers of prisoners in Saughton were confined to cells for 22 hours a day. The root problem is massive overcrowding, and I shall write further on the causes of that in a future instalment.

Shouting All Around

The long concrete and steel corridors of the prison echo horribly, and after lockdown for the first time I felt rather scared. All round me prisoners were shouting out at the top of their voices. That first evening two were yelling death threats at another prisoner, with extreme expressions of hate and retribution. Inter-prisoner communication is by yelling out the window. This went on all night into the early hours of the morning. Prisoners were banging continually on the steel doors, sometimes for hours, calling out for guards who were not there. Somebody was crying out as though being attacked and in pain. There were sounds of plywood splintering as people smashed up their rooms.

It was unnerving because it seemed to me I was living amongst severely violent and out of control berserkers.

Part of the explanation of this is that for most prisoners the new admissions wing on first night is where they go through withdrawal symptoms. Many prisoners come in still drugged up. They are going through their private hell and desperate to get medication. I can understand (though not condone) why the prison medical staff are so remarkably bad and unhelpful. Their job and circumstances are very difficult.

On that first evening I was concerned that I did not have my daily medicines, and by the next morning my heart was getting distinctly out of synch. I was therefore relieved to receive the promised medical visit.

“For most prisoners the new admissions wing on first night is where they go through withdrawal symptoms. Many prisoners come in still drugged up. They are going through their private hell and desperate to get medication.”

My cell door was opened and a nurse, flanked by two guards, addressed me from outside my cell. She asked if I had any addictions. I replied in the negative. I asked when I might receive my medicines. She said it was in process. I asked if I might get my pulse oximeter. She said the prison did not allow devices with batteries. I asked if my bed could somehow be propped or sloped because of my hiatus hernia (leading to gastric reflux) and Barrett’s oesophagus. She said she didn’t think that the prison could do that. I asked about management of my blood condition (APS), saying I was supposed to exercise regularly and not sit for long periods. She replied by asking if I would like to see the psychiatric team. I replied no. She left.

The Prison Governor

I was taken out to exercise alone, with four guards watching me. I felt like Rudolf Hess. In the lunch queue I met my first prisoners, who were respectful and polite. The day passed much as the first, and I still did not get my medicines on the Monday. They arrived on the Tuesday morning, as did the prison governor.

I was told the governor had come to see me, and I met him in the (closed) Glenesk library. David Abernethy is a taciturn man who looks like a rugby prop and has a reputation among prisoners as a disciplinarian, compared to other prison regimes in Scotland. He was accompanied by John Morrison, Glenesk block manager, a friendly Ulsterman, who did most of the talking.

I was an anomaly in that Saughton did not normally hold civil prisoners. The governor told me he believed I was their first civil prisoner in four years, and before that in 10. Civil prisoners should be held separately from criminal prisoners, but Saughton had no provision for that. The available alternatives were these: I could move into general prisoner population, which would probably involve sharing a cell; I could join the protected prisoners; or I could stay where I was on admissions.

Oxgangs, 2007: another of the places in Edinburgh often heard inside the prison. (Wikimedia Commons)

On the grounds that nothing too terrible had happened to me yet, I decided to stay where I was and serve my sentence on admissions.

They wished to make plain to me that it was their job to hold me and it was not for them to make any comment on the circumstances that brought me to jail. I told them I held no grudge against them and had no reason to complain of any of the prison officers who had (truthfully) so far all been very polite and friendly to me. I asked whether I could have books I was using for research brought to me from my library at home; I understood this was not normally allowed. I was also likely to receive many books sent by well-wishers. The governor said he would consider this. They also instructed, at my request, extra pillows to be brought to prop up the head of my bed due to my hiatus hernia.

That afternoon a guard came along (I am not going to give the names except for senior management, as the guards might not wish it) with the pillows, and said he had been instructed I was a VIP prisoner and should be looked after. I replied I was not a VIP, but was a civil prisoner, and therefore had different rights to other prisoners.

He said that the landing guards suggested that I should take my exercise and shower/phone time at the same time as other mainstream new admission prisoners (sexual offender and otherwise protected new admission prisoners had separate times). I had so far been kept entirely apart, but perhaps I would prefer to meet people? I said I would prefer that.

A Community

Houses in Granton, Edinburgh 2010: another pipeline to the prison. (Kim Traynor, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

So, the next day I took my exercise in that filthy yard in the company of four other prisoners, all new arrivals the night before. I thus observed for the first time something which astonished me. Once in the yard, the new prisoners (who on this occasion arrived individually, not all part of the same case), immediately started to call out to the windows of Glenesk block, shouting out for friends.

“Hey, Jimmy! Jimmy! It’s me Joe! I am back. Is Paul still in? What’s that? Gone tae Dumfries? Donnie’s come in? That’s brilliant.”

The realisation dropped, to be reinforced every day, that Saughton jail is a community, a community where the large majority of the prisoners all know each other. That does not mean they all like each other – there are rival gangs and enmities. But prison is a routine event in not just their lives, but the lives of their wider communities. Those communities are the areas of deprivation of Edinburgh.

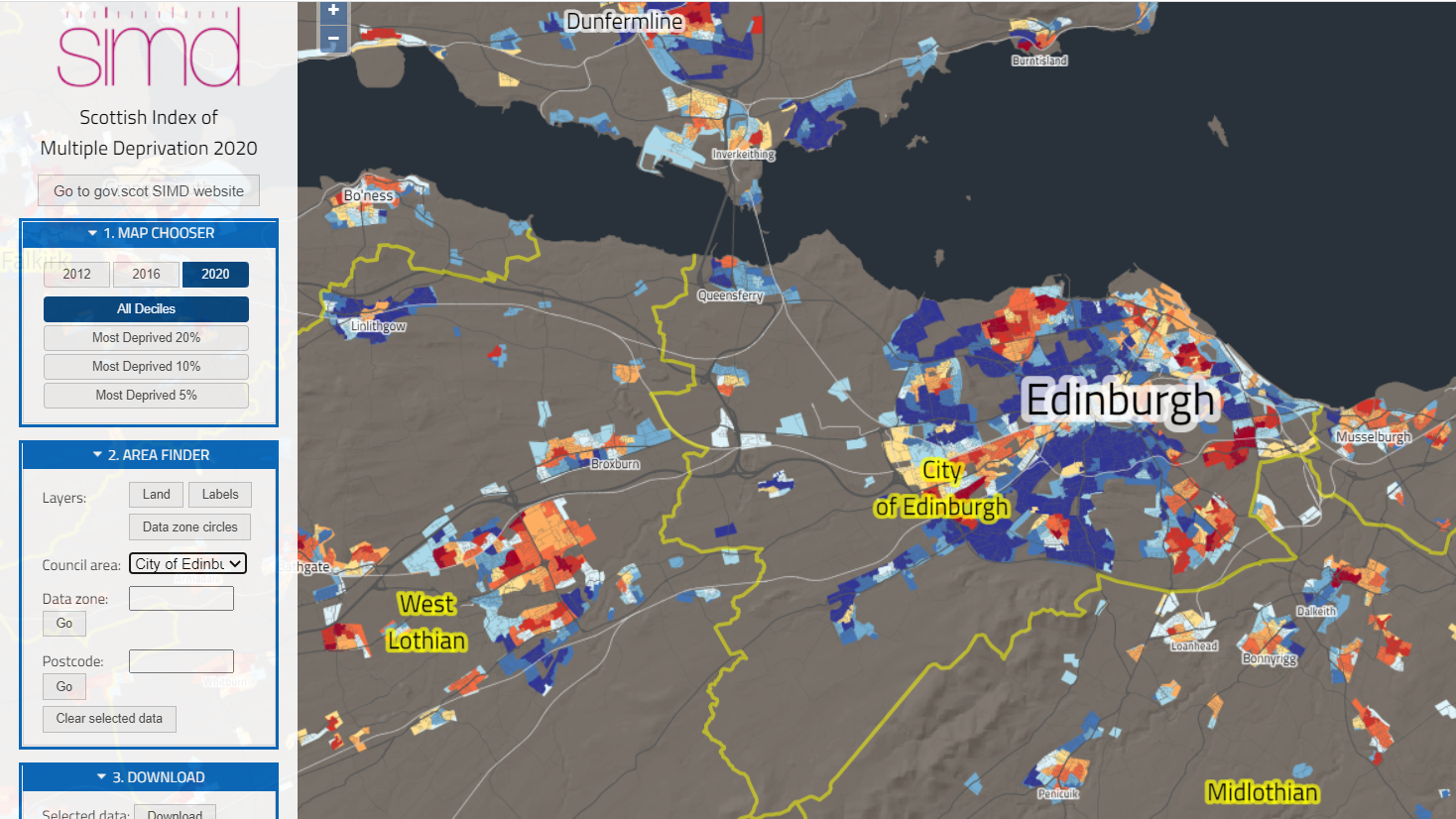

Edinburgh is a city of astonishing social inequality. It contains many of the areas in the bottom 10 percent of multiple social deprivation in Scotland (dark red on the map below). These are often a very short walk from areas of great affluence in the top 10 percent (dark blue on the map). Of course, few people make that walk. But I recommend a spell in Saughton jail to any other middle-class person who, like myself, was foolish enough to believe that Scotland is a socially progressive country.

The vast majority of prisoners I met came from the red areas on these maps. The same places came up again and again – including Granton, Pllton, Oxgangs, Muirhouse, Lochend, and from West Lothian, Livingston and Craigshill. Saughton jail is simply where Edinburgh locks away 900 of its poorest people, who were born into extreme poverty and often born into addiction. Many had parents and grandparents also in Saughton jail.

A large number of prisoners have known institutionalisation throughout their lives; council care and foster homes leading to young offenders’ institutions and then prison. A surprising number have very poor reading and writing skills. The overcrowding of our prisons is a symptom not just of failed justice and penal policy, but of fundamentally flawed economic, social and educational systems.

Of which I shall also write more later. Here, on this first day with a group in the exercise yard, I was mystified as the prisoners started going up to the ground floor windows and the guards started shouting “keep away from the windows! Stand back from the windows” in a very agitated fashion, but to no effect. Eventually they removed one man and sent him back to his cell, though he seemed no more guilty than the others.

By the next week I had learnt what was happening. At exercise the new admissions prisoners get drugs passed to them through the window by their friends who have been in the prison longer and had time to get their supply established. These drugs are passed as paper tabs, as pills or in vape tubes. There appears no practical difficulty at all in prisoners getting supplied with plentiful drugs in Saughton. Every single day I was to witness new admissions prisoners getting their drugs at the window from friends, and every single day I witnessed this curious charade of guards shouting and pretending to try and stop them.

My first few days in Saughton had introduced me to an unknown, and sometimes frightening, world, of which I shall be telling you more.

Craig Murray is an author, broadcaster and human rights activist. He was British ambassador to Uzbekistan from August 2002 to October 2004 and rector of the University of Dundee from 2007 to 2010. His coverage is entirely dependent on reader support. Subscriptions to keep this blog going are gratefully received.

This article is from CraigMurray.org.uk.

Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!

Donate securely with PayPal

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Barbaric compared to Norway or Germany.

Socially progressive?? Until the 17th December 2021. The Criminal Age of Responsibility in Scotland was 8 years of age. One of the lowest in the world. I watched Police Scotland try and frame up an 11 year old with an assault charge for allegedly throwing a pencil in a classroom. Scotland’s state agents are corrupt as any I’ve come across.

A telling and graphic reminder of the punitive penal system endemic in HM (Her Majesties) Prisons courageously described in detail by an ex diplomat unjustly convicted and imprisoned for contempt of court. His focus on the class nature of the prison population most of whom originate in the poorest neighbourhoods of Edinburgh and Glasgow spotlights the existential problem of the growing underclass in the UK whose exclusion from mainstream society is reflected in their often chaotic lifestyle of poverty, drugs and crime. Increasingly these populations of limited labour value are problematic for the ruling class

who necessarily resort to the legal system to manage impoverished communities and protect the social from political challenge.

This is just stunning. I had had no particular knowledge of Scotland, let alone Scottish prisons, aside from from the cliché kilt and bagpipe thing. For that matter, I know little of prisons in general, aside from old movies about Alcatraz. Mr. Murray’s account is enthralling–and sickening–and I’m anxious to read further communiques from him.

If you read Ian Rankin’s Rebus police procedurals, all of the names of the deprived areas around Edinburgh and Saughton prison itself would be familiar to you.

“The toilet was filthy. Below the waterline it was stained deep black with odd lumps and ridges. Above the waterline it was streaked and spotted with excrement, as was the rim. The toilet floor was in a disgusting state. The cell itself was dirty with — everywhere a wall or bolted-down furniture met the floor — a ridge built up of hardened black dirt.

A female guard looked around the cell, then came back to give me rubber gloves, a surface cleaner spray and some cloths. So, I spent my first few hours in my cell on my knees, scrubbing away furiously with these inadequate materials.”

That picture: AOC and Nicola Sturgeon hoisting their glasses of ale at COP 26. Starfckrz or Starfckees?

Doesn’t matter now, does it? Loathsome both is all that matters.

That dark, black hole whose nucleus is well hidden until a man like Craig Murray enters that evil world and exposes its darkness. The “synthetic powers that be” which prop up dying systems of “empire” around the world are beginning to awake to the realization that they are on the wrong side!

Sees like an OK place compared with U$ gulags.

I pretty much agree with you….That is why we are horrified by the frightening torture Julian Assange as bound to face.

Sadly, Charles Dickens times are alive and well in Scotland’s prisons for poor people and reporters caught in the trap of daring to question today’s political power structure/orthodoxy.

Punishing dehumanizing cruelty alive and well too.

To set up a punishing regime of grime and confinement is so depressing. To think of Scotland as a country being guilty of such dehumanising treatment is so dispiriting. Craig Murray’s confinement might shine a light on the backwardness of Scotland’s prison policy. It is obviously not a matter of the individuals involved but a matter of political neglect. I support Nicola Sturgeon but something has to change such inhumane treatment can’t be allowed to continue.

But of course, it will continue this way under Nicola Sturgeon. How many years has she been in power? And how much has it improved over that time? So why exactly do you support her?

Your last sentence: For Shame!

How can you support when she sends an upstanding citizen like Craig Murray to that place? She’s destroying what was and what could have been.

How can you support Nicola Sturgeon, who is responsible for Murray being in prison in the first place?

A fascinating glimpse into the purposely-hidden world that is the UK’s enormous prison estate. This writer spent six years in various English and Scottish prisons up to 2017 and much of what Mr Murray writes rings very true. I quibble about some details:

– HMP Edinburgh is the official name for the prison and, from my experience there in 2013 and as a correspondent with a prisoner there right now, most prisoners call it that, not Saughton.

– toothpaste does work tolerably well to affix paper or card to the wall. Sceptical readers should try it.

– any dirt in a cell is the responsibility of the person living in it, as there are cleaning materials issued on request and one day a week in which every cell is to be properly cleaned with a mop etc.

– I can attest to the mediocre quality of health care. Staff will rarely enter a cell, out of well-founded concern for their safety, so interviews are conducted either at or sometimes through the door. Privacy is not their concern.

– as for drugs, that depends on which part of a prison you are in. I spent most of my time in segregated sections, sometimes called vulnerable prisoner units. In my six years I was never offered a drug nor did I witness anyone taking any. Every morning I would see a line of men trooping to the dispensary for their methadone, which apparently is not available in US prisons.

I fully agree with Mr Murray’s general assessment. How many Scots think of the men banged up in such conditions? If they do think, I suspect they don’t care, and that applies across the political spectrum.

Similar to how in our great “Western” democracies, they try to hide the reality of their horrendously evil and punitive foreign policies.