The very act of the U.N. Secretary General accepting a Palestinian membership application was an acknowledgement from the U.N. that Palestine is already a state, since only states can apply, wrote Joe Lauria.

As a U.N. observer state, Palestine became a member of the International Criminal Court on April 1, 2015. As an article by Ilan Pappé that appears today on Consortium News says, Britain (and the United States) don’t recognize Palestinian statehood, having lost the General Assembly vote on its observer state status on Nov. 29, 2013 (by 138 in favor to nine against with 41 abstentions). This article, written on Oct. 4, 2011, argues that Palestine had already qualified as a state as it campaigned for that status at the U.N. It was the first article written for Consortium News by now Editor-in-Chief Joe Lauria.

By Joe Lauria

Special to Consortium News

A combination of mistakes, whether through ignorance or design, and significant omissions of fact have left the American public misinformed about why the Palestinians have gone to the United Nations and what they are trying to achieve.

The biggest error repeated across the media in hundreds of headlines and stories is that the Palestinians are seeking statehood at the U.N. In fact, Palestine is already legally a sovereign state and is seeking membership of the United Nations, not statehood. [It eventually opted for observer state status after the U.S. blocked membership.]

The United Nations does not grant or recognize statehood. Only states can recognize other states bilaterally. The U.N. can only confer membership or non-member observer state status to already existing states. The U.N. Charter is clear. Article 4 says that only existing states may apply for U.N. membership.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon accepted an application for U.N. membership from PLO Chairman and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas on Sept. 23. Ban sent the application to the Security Council, which began deliberating last week.

The very act of the Secretary General accepting the membership application is an acknowledgement from the U.N. that Palestine is already a state, since only states can apply.

The Montevideo Convention of 1933 lays out the requirements for statehood: a population living on a defined territory with a government that can enter into relations with other governments. The Palestinians have all three.

Though its borders with Israel are not set, other countries with border disputes have been admitted as U.N. members, such as Pakistan and India. Trygve Lie, the first U.N. Secretary-General, also wrote a 1950 memo that states do not need universal recognition to apply.

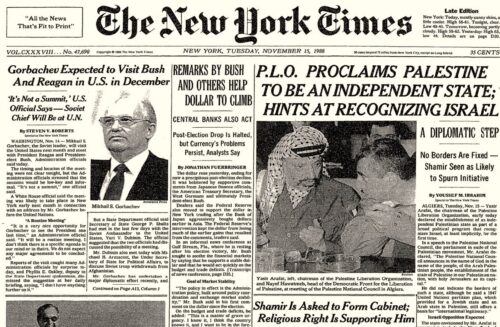

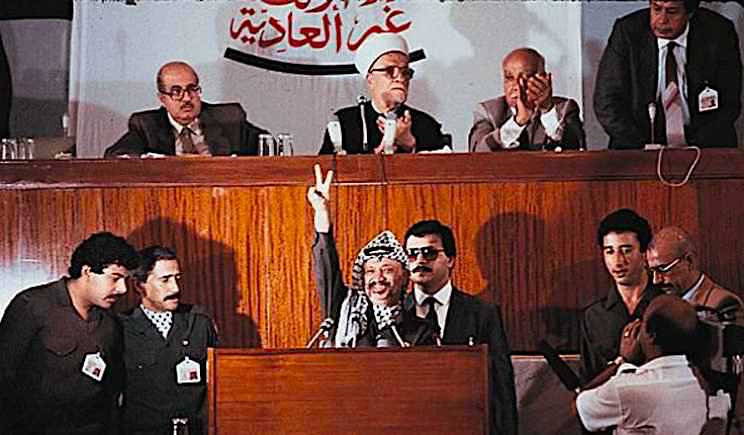

Palestine declared its independence on Nov. 15, 1988, a fact found nowhere in the American mainstream reporting of the past week. A Palestinian walked out of the Al Asqa Mosque that day in Al Quds/Jerusalem and read the declaration aloud, much as someone read the American Declaration of Independence to a crowd in the courtyard of the Philadelphia State House on July 4, 1776.

Almost immediately one hundred nations recognized an independent Palestinian state. Since then 30 more nations have recognized Palestine, some having opened Palestinian embassies in their capitals. This crucial fact too was not reported in the U.S. media. For Palestinians and those countries that recognize them, Israeli troops are occupying a sovereign nation.

It was the same as when Morocco and then France and other nations recognized an independent United States years before the war against Britain was won. For Americans and those nations recognizing America, British troops became an occupation force, not an army defending British territory.

The problem for the Americans then and for the Palestinians now is that the occupying nation and the world’s biggest power are not among the 130 who’ve recognized them.

If there were a United Nations in 1777 the Americans could have applied for membership. And if Britain had a veto on the Security Council then as it does now, it would have blocked that membership.

Today neither the occupying power, Israel, nor the world’s biggest power, the U.S., recognizes Palestinian statehood. Thus the U.S. has vowed to veto the Palestinians’ membership resolution in the Security Council.

The U.S. had furiously lobbied to prevent the Palestinians from coming to the U.N. at all, including Congress threatening to cut off all aid. Having failed, Washington is now trying to delay a vote as long as possible while lobbying the several non-permanent members of the Security Council to abstain, or vote against.

But the Palestinians knew from the start the U.N. process would take weeks and have so far not backtracked on their plan one inch.

Membership in the U.N. requires a recommendation from the 15-member Security Council, secured with nine votes in favor and no vetoes. If the recommendation passes, the 193-seat General Assembly must approve with a two-thirds majority. Eight votes in favor or less would kill the Security Council membership resolution, sparing the U.S. from a veto that would cost them dearly on the Arab street.

Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and Lebanon are among the Security Council members who have formally recognized Palestine and are firm about voting in favor. The U.S. isn’t bothering with them. But Nigeria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Colombia and Gabon have also recognized Palestine and are under extreme American, and in the case of Gabon, French pressure to at least abstain.

Falling short of eight votes would be an embarrassment for the Palestinians, but the Security Council route is only the first step. After a sure defeat in the Security Council (since the United States has vowed to use its veto if necessary), two options in the General Assembly remain.

President Abbas told reporters on his plane back home from New York that the Palestinians are willing to wait two weeks for the Security Council to act before going to the next step for membership. That step is to try to circumvent either a U.S. veto or less than nine votes in the Security Council in the General Assembly, employing a Cold War-era resolution known as Uniting for Peace.

It was introduced by the U.S. in 1950 to get around repeated Soviet vetoes on the Korean War. Francis Boyle, a legal adviser to Abbas, told me he has advised the Palestinian president to take this step.

But the Palestinians would have to convince two-thirds of voting Assembly members that Palestinian membership would be a response to a “threat to peace, breach of the peace or an act of aggression” from Israel.

The U.S. and Israel would fight to keep this off the General Assembly agenda. But Boyle, who cautioned that he does not speak for the Palestinians, told me he thinks the Palestinians have the votes to overcome this.

Nevertheless, there seems to be a split in the PLO leadership on whether to use Uniting for Peace. Hanan Ashrawi, a PLO executive committee member, says it is still a viable option. But the Palestinians’ U.N. observer, Riyad Mansour, believes any membership bid must legally go through the Security Council first and there’s no getting around it.

Abbas’ position on this is not clear. It will be interesting to see if the Palestinians try to use Uniting for Peace and what happens if they do.

If they decide against it or fail, their third option is to try to become a non-member observer state, which needs only a simple majority of 97 votes in the General Assembly which the Palestinians clearly have. [They did not use Uniting for Peace and instead gained observer state status.]

Becoming an observer state would be more than symbolic. It could reshape the balance of power between Israel and the Palestinians. As an observer state, Palestine could participate in Assembly debates, but could not vote, sponsor resolutions or field candidates for Assembly committees.

But more importantly, it would allow Palestine to accede to treaties and join specialized U.N. agencies, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the Law of the Sea Treaty, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the International Criminal Court (ICC), officials said.

Switzerland joined the ICAO in 1947 when it was still an observer state before becoming a U.N. member in 2002. Denis Changnon, an ICAO spokesman in Montreal, told me the treaty gives members full sovereign rights over air space, a contentious issue with Israel, which currently controls the airspace above the West Bank and Gaza.

The Palestinians could bring claims of violation of its air space to the International Court of Justice.

If Palestine joins the Law of the Sea Treaty it would gain control of its national waters off Gaza, a highly contentious move as those waters are currently under an Israeli naval blockade. Boyle said he has advised Abbas to accede to treaties, including the Law of the Sea. If they do, the Palestinians could challenge the Israeli blockade at the ICJ as well as claim a gas field off Gaza, currently claimed by Israel.

Even more troubling for Israel and the U.S. would be Palestine joining the International Criminal Court [which it eventually joined on April 1, 2015.]

Ambassador Christian Wenaweser, president of ICC Assembly of State Parties, said in an interview a Palestine observer state could join the ICC and ask the court to investigate any alleged war crimes and other charges against Israel committed on Palestinian territory after July 2002, including Israel’s 2008-2009 Operation Cast Lead war against Gaza that killed 1,400 Palestinian civilians, [which Palestine has since done.]

Ashrawi says Israeli settlements in Palestine can be challenged as war crimes in the court as a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The Palestinians know they must still negotiate borders, refugees, settlements, the occupation and Jerusalem. Abbas said pushing for U.N. membership did not mean he no longer wants to negotiate. Rather gaining membership or observer state status would give the Palestinians more leverage in those talks, he said.

In an effort to upstage and derail the Palestinians’ membership drive, just minutes after Abbas and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had finished addressing the General Assembly last Friday the so-called Quartet, the U.S., U.K., Russia and the U.N., announced its vision of a one-year plan for a comprehensive settlement.

The Quartet dropped its repeated call for a settlement freeze and called for no preconditions for talks. The Palestinians, who are demanding a freeze before negotiations based on the pre-occupation 1967 borders, rejected the Quartet’s plan. Israel then announced 1,100 new settlements in occupied East Jerusalem.

The Quartet has failed again. Westerners cannot solve this problem. Maybe it’s time to make it the Quintet by adding the Arab League, to give voice to the Palestinians. How to get the U.S. media to become interested in more accurately reporting the Palestinian’s side of the story is another matter.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional work as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

Please Support Our

Fall Fund Drive!

When Joe Lauria wrote this article in 2011, he didn’t probably think that Israelis would turn “negotiating borders, refugees, settlements, and occupation of Jerusalem” into such a nightmarish tangled web that would be impossible to untangle it again. The two state solution is dead. As Ilan Pappe in his article put it, the two state- “solution has been in the Morgue for quite a while, but nobody dares to have a funeral”.

This purely a legal look at what constitutes a state and that Palestine met those requirements. The situation on the ground is another matter.

The independent state of Palestine ,recognized by all , is inching it’s way into reality ,regardless of US / Israel blocking .

This issue ,I would submit ,is and has been the main wedge preventing world peace from being realized .Gods speed on making it happen.