As`ad AbuKhalil says a new biography seems to introduce the reader to someone the Middle East scholar clearly was not.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Two books were published recently about Middle East scholar Edward Said: Edward Said: His Life as A Novel by Dominque Edde and Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said, by Timothy Brennan. Edde is a Lebanese-French writer whose book is a very personal — sometimes too personal — account of her love affair with Said. Her book was translated from French.

Two books were published recently about Middle East scholar Edward Said: Edward Said: His Life as A Novel by Dominque Edde and Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said, by Timothy Brennan. Edde is a Lebanese-French writer whose book is a very personal — sometimes too personal — account of her love affair with Said. Her book was translated from French.

We will review the book by Brennan, a professor of comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, who has written what has already become a definitive biography of the complicated man that Edward Said was.

It is not easy to write about Edward Said; the man was multi-dimensional and his life and mind were both rich. A biographer has to contend with his work in comparative literature and literary criticism; his politics, diplomacy and activism in Palestinian affairs; his writings on classical music; and the person Said was.

Brennan does a masterful job charting the personal life, aided by Said’s family, who opened his private papers and letters to him. Much work went into the book to take the reader on a journey of Said’s full life. In comparative literature, Brennan is supremely qualified to talk about writers and philosophers who he has written about. Yet, there are major problems in this biography.

Brennan does a masterful job charting the personal life, aided by Said’s family, who opened his private papers and letters to him. Much work went into the book to take the reader on a journey of Said’s full life. In comparative literature, Brennan is supremely qualified to talk about writers and philosophers who he has written about. Yet, there are major problems in this biography.

So much of the personal and political life of Said intersected with the political turmoil of the Arab world and the history of Palestinian struggle for liberation.

No Arab Expert

Brennan, while diligent in research, is not an expert on Arab politics —and it shows. Furthermore, he does not know Arabic, and the life of Said was increasingly Arab and Arabic, especially after 1967, though the book does show Said was very much alert to Arab politics and identity long before 1967.

Said increasingly spoke to Arabs exclusively in Arabic and would consume Arabic media as much as Western media. For instance, he would watch Aljazeera Arabic service in his later years. That is a world that is very unfamiliar ground for Brennan.

Worse, while Brennan concedes that he is not an expert on the Middle East, he informs us that he relied on the views of a certain Syrian opposition figure in Beirut, Muhammad Ali Atassi, whose politics are clearly different from — if not diametrically opposed to — those of Said.

Brennan also relied on Sadiq Jalal Al-Azm, one of Said’s most bitter enemies.

Al-Azm was a leftist Syrian intellectual and polemicist who was known for his sharp criticism of other Arab intellectuals with whom he disagreed, for calling them spies for the Americans or the Israelis, or both. He basically called historians Walid Khalidi and Hisham Sharabi traitors because they met in the 1970s with Harvard Professor Roger Fisher (See Al-Azm’s book, Ziyarat As-Sadat and Bu’s As-Salam Al-`Adil.)

But like many of his contemporaries, Al-Azm underwent a major ideological transformation in his later years, and became a rather conservative critic who called for Western military intervention in Syria and who — a man known for his avowed atheism — would make sectarian statements about the war in Syria.

To constantly take Al-Azm’s side, or to reference him in criticism of Said, as Brennan has done, is a betrayal of Said and his legacy, given the bitter feud between the two men.

Meeting Al-Azm

Sadiq Jalal Al-Azm in 2006. (Bgadsby, Wikimedia Commons)

I recall when I was frequently meeting with Al-Azm in Washington in 1992 when he was spending the year at the Wilson Center. Said heard of my meetings and was quite alarmed; he called me and warned me about him.

He told me about their years-long feud and said that Al-Azm was only invited to the U.S. (“by the Princeton Zionists”) in order to spite Said, or to use him against Said. I later learned that Said was right.

Al-Azm that year asked me to intercede with Said in order to reach reconciliation with him. When I brought this up to Said, he was furious and adamant against any reconciliation and told me that Al-Azm’s positions were then in line with Zionist interests.

There was no Arab intellectual who Said despised and detested more than Al-Azm, with the possible exception of Fouad Ajami. And just like Adam Shatz, in his review of Brennan’s book in the London Review of Books, Brennan treats Al-Azm’s book, Self-Criticism After the Defeat favorably. (The book was recently translated into English with a forward by the late Lebanese reactionary, Ajami, who was awarded a medal by George W. Bush for his propaganda services during the Bush years).

There was no Arab intellectual who Said despised and detested more than Al-Azm, with the possible exception of Fouad Ajami. And just like Adam Shatz, in his review of Brennan’s book in the London Review of Books, Brennan treats Al-Azm’s book, Self-Criticism After the Defeat favorably. (The book was recently translated into English with a forward by the late Lebanese reactionary, Ajami, who was awarded a medal by George W. Bush for his propaganda services during the Bush years).

Al-Azm’s book is, in fact, a racist catalogue of Arab personality flaws, disorders and illnesses. Such racist work is described by Shatz as a “blistering anatomy of the Arab military failure.” It was not. It was a character assassination of every Arab human on this planet.

Al-Azm does not think that Arabs lost the war in 1967 for the obvious reasons: that the West ensured the military superiority of Israel against any combination of Arab armies. Instead, he proposes that Arabs lost the war due to shortcomings in their personality.

Ghassan Kanafani wrote a blistering attack on Al-Azm’s book in Al-Anwar in 1968, and sarcastically asked Al-Azm how those Arab personality disorders have escaped him since he believed in the personal or mental inferiority of Arabs. Al-Azm’s book is in the same genre as the notorious racist book by the Israeli anthropologist Raphael Patai, titled The Arab Mind.

Coddling Harkabi

The attempt by Brennan to reconcile the legacy of Sadiq Al-Azm with that of Said does not do justice to Said (nor to Al-Azm for that matter).

Not only does Brennan not criticize Al-Azm’s work, but he goes further by giving favorable treatment to Israeli war criminal Yehoshafat Harkabi, a former head of Israeli military intelligence, whose “clever innovations,” according to Noam Chomsky, were “the letter bombs in the Gaza Strip in the 1950s.”

The Israeli delegation to the 1949 Armistice Agreements talks, with, from left: Yehoshafat Harkabi, Aryeh Simon, Yigael Ladin, Yitzhak Rabin. (Israeli GPO photographer, Wikimedia Commons)

To be fair, Brennan does cite that reference in his book. But Brennan fawns over Harkabi, describing him as “deeply cultivated, a lover of Arabic poetry” and “fabulously literate.” This is like talking about Hitler saving candy for Goebels’ children.

Harkabi published his famous book Arab Attitudes to Israel in 1971 and it became a classic in Zionist propaganda, distributed by Israeli embassies worldwide. Brennan describes Harkabi’s book as a “political dissection of the Arab psyche.” This academic legitimization of Harkabi’s notorious work is divergent from Said’s important legacy.

Long before MEMRI (which specialized in unearthing grotesque statements by every Arab on earth), Harkabi established the practice of collecting only hateful speech by Arabs in order to undermine the legitimate grievances of the Palestinian people. He wanted to argue that Arabs are just like Nazis and that they opposed Israel because they don’t like Jews.

Kind to Malik Too

Brennan’s ignorance of Arab politics and culture is also revealed in his treatment of Charles Malik, who was related to Said and who influenced Said in his early years. Malik was a notorious right-wing reactionary who was known in the U.S. in the 1950s due to his propaganda efforts against communism and leftism in general.

Malik advised Said on his education early in life but Said broke with Malik and bitterly opposed his role in the Lebanese civil war, during which Malik was one of the key advisers to war criminal Bashir Gemayyel, who was a tool of the Israeli government. Malik advocated for the alliance between the fascistic Lebanese Forces militia and Israel.

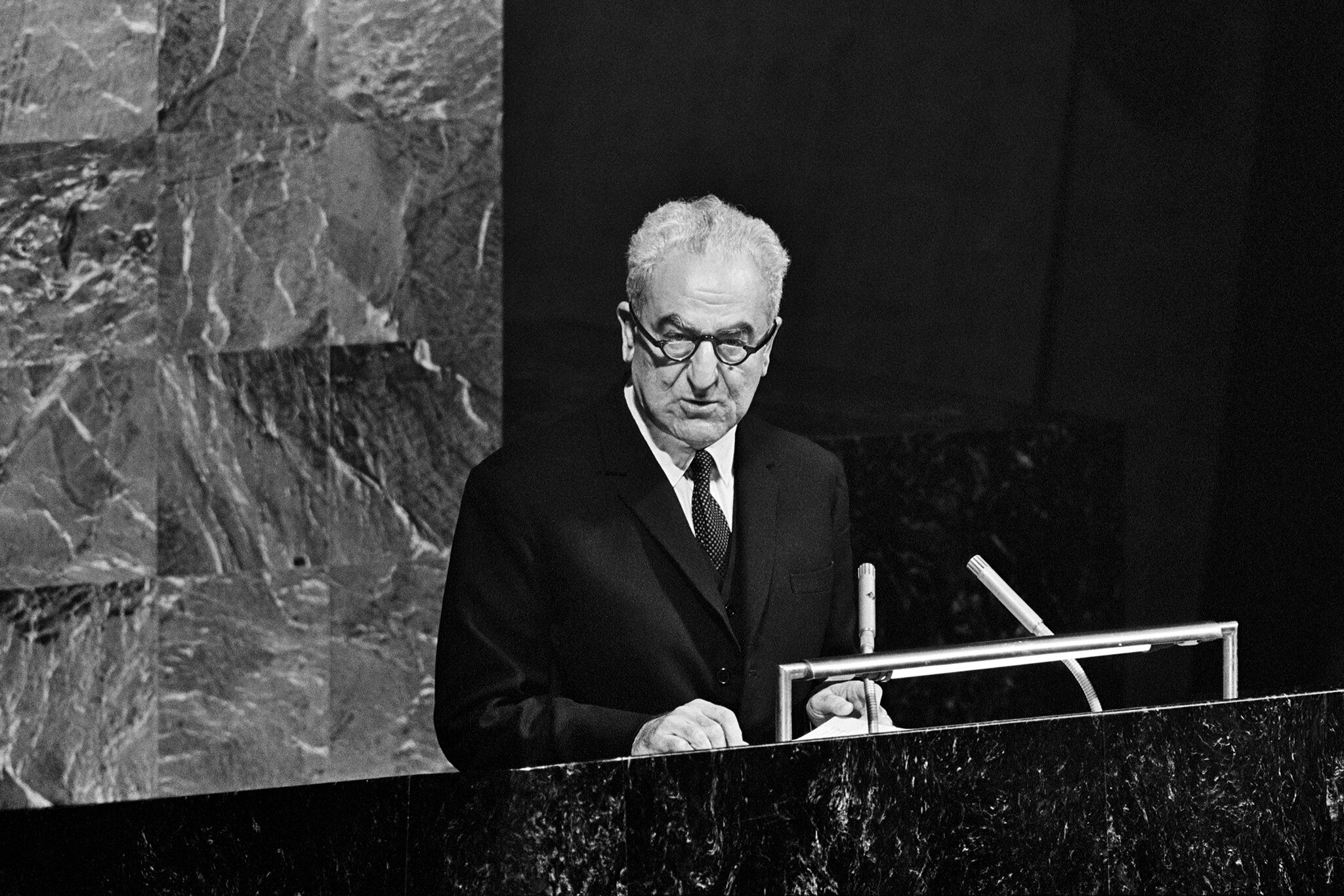

Dec. 9, 1968: Charles Habib Malik addressing the UN General Assembly. (UN Photo)

But Brennan insists that Malik was an Arab intellectual though the man was opposed to anything Arab, and whose ideology was based on the categorical rejection of the Arab identity of Lebanon. Moreover, Malik did not write much in Arabic (Brennan clearly does not know that) and his role was largely political in the 1958 civil war. (Brennan mentions that Malik served in parliament but he only served once in 1957 when the CIA rigged the Lebanese election to ensure majority support for the right-wing president, Kamil Sham`un.)

There are other problems in Brennan’s book. He talks about Said being afraid for his life in Lebanon in 1973 allegedly because he wrote against car bombs, as if Arabs are great champions of car bombs when the only perpetrators of car bombs at the time, and since the 1940s, were the Zionists. Israel was also the first to introduce car bombs in the Lebanese civil war, after which some Arab groups would adopt the tactic.

Said was not even known in 1973. But since the late 1970s he has remained one of the most widely admired Arab intellectuals — uniquely so by Islamists and secularists alike.

Transformation Missing

Brennan talks about Said losing friends to assassinations in Beirut, implying that they were assassinated by fellow Arabs. In fact, Said’s friends (like Kamal Nasser and Abu Omar) were assassinated by Israel or their surrogate militias. Omar was killed by pro-Israeli militias in Lebanon, but Brennan maintains that his murder was “assassination under obscure circumstances.” There was nothing obscure about the assassination: Omar and his comrades were traveling by boat from Beirut to Tripoli and the area was under the control of the Phalanges and their Israeli sponsors.

Also missing in Brennan’s biography is an account of Said’s political transformation. Said, who became known in the Arab world in 1977 — when then Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, of all people, recommended him as a president of a Palestinian government-in-exile — was a staunch advocate of the two-state solution, but later shifted to a one-state solution.

Said in the fall of 1992, after attending my debate in New York City with Judith Miller, walked with me outside and said: increasingly I am finding myself gravitating toward your side, in reference to the rejectionist front of George Habash.

There is no mention of Hizbullah leader Hasan Nasrallah in the book, though Said admired the Lebanese resistance model against the Israeli occupation, and sought after and met Nasrallah after the Israeli humiliating withdrawal from South Lebanon in 2000.

Although it was the Amal Movemnet that drew members away from leftist organizations, long before Hizbullah was established in the mid-1980s, I was by the 1990s, like most leftists who came out of the Lebanese civil war experience, embittered against Hizbullah. Clovis Maksoud and Said would speak to me about the historical significance of the model of resistance that Hizbullah was mounting in South Lebanon.

Those Arab aspects of Said’s personality are totally missing from Brennan’s biography and instead the reader is introduced to a man who seems like a typical white Western liberal — which he certainly was not.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002) and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He writes a twice monthly column for Consortium News and tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Thank you for the highly informative article about Edward Said. Please do write more about Said’s legacy (specially with regards to Palestine), as the new generation of people everywhere should know more about this great Palestinian born intellectual.

Thanks for this excellent article

Educational as usual. Thanks

Will you follow this up with a review of the autobiography written by Dominque Edde?

~

I really appreciate this and I’m going to study up on my own account regarding Edward Said. I suspect I will be able to find much information, but the challenge is always getting to the heart of the matter and that takes discretion. Discretion, if you want my opinion, which I will give, is in short supply these days.

~

Thanks and best to you,

BK

I reviewed it in Arabic alas

Wow. What a devastating review of Brennan’s book. What is so impressive is that this review is devoid of a single ad-hominem. Very simple dissection of the Brennan’s arguments and left at that. That is refreshing.