Ashley Poust and Daniel Varajão de Latorre say the answer highlights the degree to which the fossil record is incomplete.

(1Ado123/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

By Ashley Poust and Daniel Varajão de Latorre

The Conversation University of California, Berkeley

During 2.4 million years of existence on Earth, a total of 2.5 billion Tyrannosaurus rex ever lived, and 20,000 individual animals would have been alive at any moment, according to a new calculation method we described in a paper published on April 15, 2021 in the journal Science.

During 2.4 million years of existence on Earth, a total of 2.5 billion Tyrannosaurus rex ever lived, and 20,000 individual animals would have been alive at any moment, according to a new calculation method we described in a paper published on April 15, 2021 in the journal Science.

To estimate population, our team of paleontologists and scientists had to combine the extraordinarily comprehensive existing research on T. rex with an ecological principle that connects population density to body size.

From microscopic growth patterns in bones, researchers inferred that T. rex first mated at around 15 years old. With growth records, scientists can also generate survivorship curves – an estimate of a T. rex‘s chances of living to a given age. Using these two numbers, our team estimated that T. rex generations took 19 years. Finally, T. rex existed as a species for 1.2 to 3.6 million years. With all of this information, we calculate that T. rex existed for 66,000 to 188,000 generations.

From the fossil record alone, we had generated a T. rex turnover rate. If our team could estimate the number of individuals in each generation, we would know how many T. rex ever lived.

Sara Volz, CC BY-ND

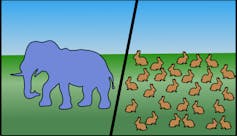

In ecology, there is a well-established relationship between body mass and population density called Damuth’s law. Larger animals need more space to survive – one square mile of grassland can support a lot more bunnies than elephants. This relationship is also dependent on metabolism – animals that burn more energy require more space.

Paleontologists have come up with a range of good estimates of T. rex’s body mass and have also estimated its metabolism – slower than mammals but somewhat faster than a large modern lizard, the Komodo dragon. With Damuth’s law, we then estimated that the ancient world held about one T. rex every 42.4 square miles (109.9 square km). That’s about two individuals in the entire area of Washington, D.C.

Now we had all the pieces we needed. Multiplying the population density by the area in which T. rex lived gives us an estimate of 20,000 individuals per generation.

(Franz Anthony, CC BY-ND)

Why It Matters

Once we figured out the average population size, we were able to calculate the fossilization rate for T. rex – the chance that a single skeleton would survive to be discovered by humans 66 million years later. The answer: about 1 in 80 million. That is, for every 80 million adult T. rex, there is only one clearly identifiable specimen in a museum.

This number highlights how incomplete the fossil record is and allows researchers to ask how rare a species could be without disappearing entirely from the fossil record.

Beyond calculating the T. rex fossilization rate, our new method could be used to calculate population size for other extinct species.

What Still Isn’t Known

Estimates about extinct animals always include some amount of uncertainty. Our estimate of T. rex population density ranges from one individual for every 2.7 square miles (7 square km) to one for every 665.7 square miles (1,724 square km). But surprisingly, the largest source of this uncertainty comes from Damuth’s law. There is a lot of variation in modern animals. For example, Arctic foxes and Tasmanian devils have similar body mass, but devils have six times the population density.

Further study of living animals could tighten up our estimates on T. rex.

We also don’t know fossilization rates of other long extinct dinosaurs. If we have many fossils of one species, does that mean they were more common than T. rex, or do we simply recover their fossils more often?

(Evolutionnumber9/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

What’s Next

This study might lead to other hidden facts about T. rex biology and ecology.

For instance, we might be able to learn whether T. rex populations fluctuated up and down with Triceratops – similar to wolf and moose predator and prey relationships today. However, most other dinosaurs do not yet have the incredibly rich data from decades of careful fieldwork that allowed our team to tally up T. rex.

If scientists want to apply this powerful technique to other extinct animals, we’ve got some more digging to do.![]()

Ashley Poust is research associate in paleontology at the University of California, Berkeley and Daniel Varajão de Latorre is a Ph.D. student in paleontology at the University of California, Berkeley.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please Support Our

Spring Fund Drive!

Are there any calculations pertaining to the percentage of total creature fossils that may have been lost at plate boundaries…subducted under? How bout coastal sedimentary rock (which should have been pretty fossil rich?) having been broken up by waves? Get the feeling, though, there’s a bunch of gaps re evolution on dry land as well. Could more fossils be waiting down in the ancient land bridges (around SE Asia/Australia, or…down with the [less believable] sunken “continent” of Mu)?

The time lapse plate movement vid at the Cosmos Magazine site goes from 500 mil yrs to present, but moves too fast for me to think of what might have evolved where. It sort of looks like not much “land” was lost anywhere.

So how do we reconcile that with the human population density?

Well, given that they speculate the total numbers of T-Rex at any given moment could be counted in the the thousands, the fact they lived on for so long was due to stability in the planet’s conditions versus their ability to spread everywhere.

~

Then a big rock out of space came and it was too much for them and for so much of the other life on the planet.

~

Lucky for “us” this happened because if not, just like the baby in the story below, most of us probably would of been eaten just after we were born….or we would of never been born in the first place. So think about that if you want to think with a long term perspective. Still, after the dust settled we arose and we are so acclimated to this planet it is as if the two of us were meant for each other. We just need to realize that we are not alone. We need to realize that without all of the diversity, the planet will suffer and become like just the others in the universe that have no life at all. If we realize this, and we choose to take care, then maybe the future will be boundless.

~

Whatever, the take away message for me is we have got to figure out a way to live sustainably for the long-term and we should be smart enough to know how to do this. It might mean some ideas that have taken hold need to be exposed for how wrong they are or it might mean that we need to learn another hard lesson about what is really important. If nothing else, we should all respect the fragility of life and have some reverence for forces that are outside control of any conception.

~

That I think is why humility is the key for long-term survival. Otherwise, we will demonstrate that we were no better than T-Rex, and in fact, it would be worse. Think about it. Wouldn’t it be worse if we killed ourselves off consciously versus an outside event killing us all off. If that happens, then I hope the spiritual powers of the universe recognize that a species such as ours should never occur because we have no respect for life. If not for the big rock, a T-Rex might be meandering around where I’m at just now and it would think nothing of eating a little baby coming out of an egg.

~

BK

OK, consider this hypothetical.

~

You are a little baby – came from an egg and you just were born.

~

Your momma died when she birthed you – she just bled to death. The blood was all over you.

~

You look up in your helplessness and in your face is a T-Rex!

~

It eats you up and then you are dead as well.

~

Man, life on planet earth is a bitch.

~

Still, now you can with your momma again.

~

I’m glad that rock from space

killed all the T-Rex, cause if not I wouldn’t be typing this.

Predatory assholes they were – I doubt they would have ever gotten “smart”.

~

Now we are so smart the only thing left to learn is how to live in peace.

Seems like a 50/50 chance to me just now.

No wonder so many are depressed.

The chance should be so much

better, but they

ain’t.

~

end of hypothetical

BK

Very interesting article – it’s good to read about natural history for a change, as opposed to politics and foreign relations, which are though important increasingly depressing.

One quibble: The above picture of the T-Rex seems inaccurate, as I think these dinosaurs had feathers. In fact, they were something like gigantic, meat-eating chickens. (Actually, birds are the only surviving member of the dinosaur family.)

An average population of 20,000 individuals alive at any time, over a period of 1.2 to 3.6 million years, which presumably varied significantly depending on weather conditions, droughts etc., seems a bit low to ensure the survival of the species. But then I’m not a biologist, and the T-Rexes didn’t survive either, for that matter.

It’s intriguing to imagine how the American West looked back when the T-Rex lived there – much warmer, wetter, with far different animal and plant life. Living in innocent bliss until the meteor struck.