As`ad AbuKhalil boils down what’s left of the U.S. president’s campaign promise to hold the Saudi crown prince accountable for the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi.

Joe Biden, at left, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in March 2016 during a visit by the U.S. vice president to Israel. (CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

After much anticipation, the U.S. government released a declassified, four-page report on the CIA’s conclusions about the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi.

After much anticipation, the U.S. government released a declassified, four-page report on the CIA’s conclusions about the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi.

The report squarely blames Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman (MbS), the actual ruler of Saudi Arabia, for the crime. The report clearly links the assassination of Khashoggi with other targeting of Saudi dissidents by MbS, but it gives no details at all —perhaps to provide extra political protection for the crown prince.

MbS’ responsibility for the murder (and for all crimes in Saudi Arabia during the reign of King Salman) has never been in doubt. But it is healthy to always exercise some skepticisms toward any U.S. intelligence reports which are released to the media for political reasons.

The report was hailed by the Biden administration and its supporters as evidence of its determination to link its foreign policy to human rights.

Carter’s Friends & Dictators

But this is not the first time a U.S. president has linked his foreign policy to human rights. Jimmy Carter hailed his own human-rights advocacy in office, while known for championing Anwar Sadat, Saudi Crown Prince Fahd, Pakistan’s Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq and the Shah of Iran, among many other dictators armed and supported by the U.S. government during the Cold War (and after).

Carter still lists Sadat as his best friend and source of inspiration, while Sadat was one of the worst dictators in Egyptian history (until the arrival of another pro-U.S. dictator, Gen. Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi, in Cairo in 2014).

The U.S., refreshingly, only dropped its human rights pretense under President Donald Trump. Trump was more honest than other presidents in conceding that U.S. foreign policies are determined by economic and political factors, and have little to do with human rights and democracy.

Even the right-wing Elliott Abrams, in his book Realism and Democracy, admitted that human rights did not play a role in shaping U.S. foreign policy — even under George W. Bush who made “freedom” his catch word.

Biden was a traditional realist in foreign policy as a senator. He supported all the pro-U.S. despots around the world and was known for championing Israeli occupation and aggression. He once described Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak as “family” and supported all U.S. Middle East wars.

But in Obama’s White House, Biden was in fact less hawkish and less pro-war than Obama and his aides (see the biography of Biden by Evan Osnos, Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now).

Biden’s Shifting Views

U.S. President Barack Obama at far left, with Jamal Khashoggi to his left, during a June 4, 2009, roundtable. (The White House, Wikimedia Commons)

Biden in the Obama White House was far more liberal than Biden as a senator. He supported same-sex marriage before Obama and most Democratic leaders, and he recommended diplomacy over war. It is possible that Biden has been freer as he has no more campaigns to run, and no special interests to attend to. Furthermore, his advanced age makes his lack of political ambition liberating.

Yet, Biden is part of a ruling establishment and his foreign policy team — with the possible exception of Robert Malley, the U.S. envoy to Iran —consists of people who represent the traditional foreign policy/war establishment.

When running for president, Biden expressed strong views about the Saudi regime and the murder of Khashoggi, the Washington Post columnist, which became a central preoccupation for the D.C. media elite.

Decades of Israeli killing of Palestinians was of no concern to the mainstream media, but they took the murder of Khashoggi personally, because he was writing for the Post, a main outlet of the media elite (regardless of the extent to which Khashoggi actually wrote his articles).

Biden promised to hold bin Salman accountable for the crime of killing Khashoggi and he even described the Saudi regime as “pariah” — a label that the U.S. reserves for its enemies.

But the Biden administration, unsurprisingly, failed to deliver on its promise. It not only failed to hold bin Salman accountable for the crime, but it has not treated the Saudi regime like a “pariah.”

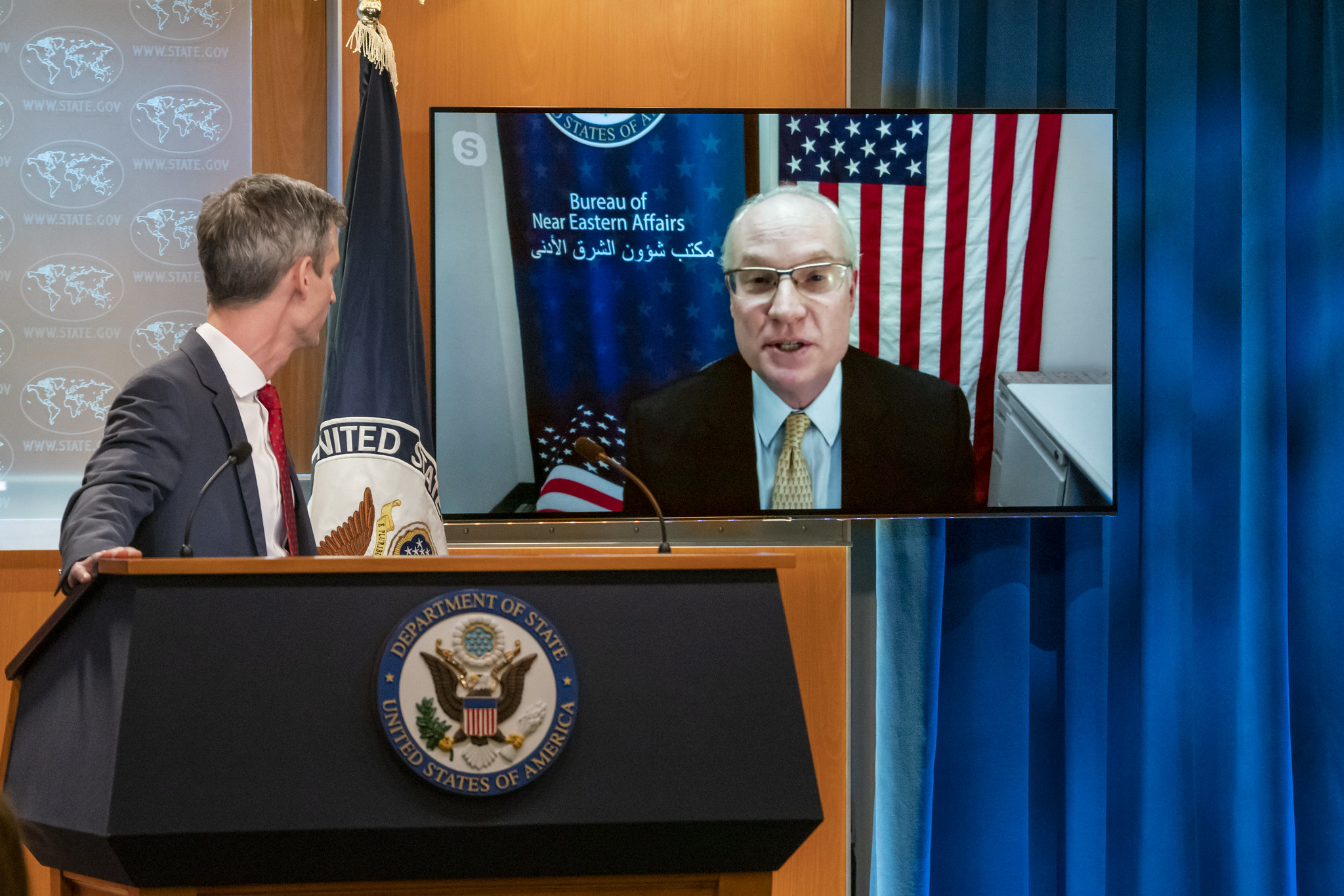

Saudi newspapers have been filled in recent days with stories of meetings and phone conversations between Saudi and U.S. officials. Central Command reassured the Saudi regime of the alliance between the two countries and the Near East Bureau of the State Department hailed the Saudi government for its generous help to the people of Yemen (actually, U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen Tim Lenderking delivered that message of American gratitude to the Saudi finance minister).

U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen Tim Lenderking, on screen, at State Department daily press briefing on Feb. 16, 2021. (State Department, Ron Przysucha)

Lloyd Austin III, the new secretary of defense, spoke with MbS and stressed U.S. commitment to defend the regime, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke with his Saudi counterpart (a cousin of MbS and a member of the royal family).

Biden’s toughness on MbS has been reduced to a reluctance to speak directly to him, although he did speak with his father, the king, who is something of an MbS hostage. We are told that Biden firmly insisted that the crown prince not be present during the phone call. But how could Biden know whether MbS was in the room or not? It’s most likely that he was there, coaching his father.

The Biden administration is simply following in the footsteps of the previous administration: prioritizing arms sales, regional domination and services to Israel in its policies in the Middle East. At the same time, it preserves the myth of U.S. concern for human rights by taking up violations in a handful of countries that don’t follow U.S. dictates.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, left, with U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, 2016. (Wikimedia Commons)

Thus, the U.S. is concerned over human rights in Russia and Venezuela but not in the UAE where the prison sentence for the “wrong tweet” reaches 15 years. Biden is, like all Democratic and Republican presidents, trying to have it both ways: to preserve the U.S. regional tyrannical order while claiming — merely rhetorically — that his foreign policy upholds human rights.

Biden is sounding firm about MbS while all his subordinates are reassuring Saudi regime officials — often cousins of MbS and even MbS himself — that the U.S. is committed to defending “the country” — which basically means defending the regime against domestic opposition and foreign threats.

Biden’s policies sound farcical: the U.S. is planning to punish subordinates of MbS, whom it knows did not plan those murders; they simply committed them on behalf of the one-man ruler. None of the 76 Saudis who are slapped with a ban are responsible for a decision that was taken by MbS. It is this one man who is spared any punishment by the tough administration of Biden.

Moreover, the Biden administration’s “calibration” of its policies toward the Saudi regime seem to mysteriously echo the recommendations of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (long considered the research arm of the Israeli lobby). One of the co-authors of the report was Dennis Ross himself, who was previously paid by Elliott Brody to write a pro-Saudi-regime article in The Hill. Ross delivered on many occasions and he urged the U.S. to stand behind the Saudi despot, who he dubbed as “revolutionary”.

Trump was correct: none of those Gulf emirates, sultanates, sheikhdoms and kingdoms would have lasted if it was not for Western (chiefly American after the 1960s) military and political support.

In the 1960s, many of those archaic regimes were tottering during the heyday of Nasserist Arab nationalism. Israel and the West threw their lot in with the most reactionary forces in the Arab world and invested heavily in the destructive 1962-70 war in Yemen. (Typically, the U.S. was on the side of the reactionary, conservative monarchy, while Nasser was supporting the progressive republican forces).

The fate of MbS is in Biden’s hands and the president has made a determination — most likely at the behest of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with whom Biden spoke for an hour — to keep MbS in power.

Had Biden declared MbS persona non grata, it would have made it easier for opponents of MbS to take over. Now, MbS has been saved and the man who saved him had falsely promised to hold him accountable for his crimes. That man called the regime that he is now pledging to defend a “pariah” — but that was when he was running for office. That was a very long time ago.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

The Angry Arab has hit another nail right square on the head. Every observation is backed up with solid facts. But it will be hard for the general American public to get access to his soft of analysis. Instead, they’ll hear how “political realities” are forcing Biden to make the moves, and non-moves, that characterize his response to the latest Saudi maneuvers.

The whitewashing hypocrisy was inevitable. Like the Egyptian dictator, MBS is our bitch not a designated enemy. The media will shortly move on back to fulminating about the crimes of the Iranians and Venezuelans.

Oh Mr Nichols, worry not. NPR has been on Russia’s, China’s, and to a lesser extent Iran’s, repeatedly over the past weeks. And NPR is the American version of VOA…

Moreover, NPR has begun to raise, that USian Orwellian machine, has begun to raise, slowly, quietly Venezuela again…NK will be just down the road a bit…

Meanwhile do we hear a dicky bird about Julian Assange’s treatment? About the UK-US treatment of the Chagos Islanders? the Us treatment of the Marshall Islanders? Gitmo? Those CIA torture set ups, actions? Nah……Nary a dicky bird. We are the whited sepulchers of the world…Ho ho…

The US serves Israel, and the Saudis when that is not inconsistent, but not the Washington Post, nor journalists’ outrage for their dead friends.

Right now, it is inconvenient to the anti-Iran project to admit this problem, so the US doesn’t.

When did Biden ever let a grizzly cold-blooded murder of an American citizen interfere with an arms deal? Surely Turkey will demand its cut.

That’s the trouble with this country. No one at the top stands on principle based on right and wrong.

Most sane people would say that murdering a journalist in cold blood for publishing findings is a crime.

Who can respect a government, a president, with feet of clay who doesn’t stand for anything.

A petulant immature ruthless child gets the better of him.

Who can trust such a government?

Especially when we know that vulnerable unconnected people in this country are jailed for years using three strikes and you’re out for a bit of marijuana (sometimes planted on them)?

It stinks.

“Principle based on right and wrong” is violated by “moral relativists” and assorted “X apologists”. The way it works in USA and allied countries is that a huge effort is spent on determining who is good and who is bad. Once X is duly determined to be very bad, that people objecting to that determination or to conclusions like “starving the country ruled by X is good” are “X apologists”.

Similar efforts determine good people. We can start with the obvious, if I recall, Senator Schumer said on TV “You must remember that we are the good guys”. People who cooperate with “the good guys” are good.

Thus MbS is a vexing case. An energetic monarch in the style of absolute rulers in European history, say, Henry the 8th or Ivan the Terrible, he embarked on an ambitious program to round up all possible opponents and squeeze them out of their money. At the start of this project I was doubting if it is possible, as the competing princes were fabulously rich with plenty of properties around the world and with plenty of influential friends, be it business, governments, think tanks, media, they had it all. But by torturing them a bit, he forced production of legal documents passing their properties away, some were killed for a good measure. Certain Lebanese president got caught in this melee for a short time.

Non-elite and infidels (heretics) in Yemen and eastern KSA got much harsher treatment. None of that caused any trouble for MbS, apparently all friends of other princes were mercenary, like think tanks that would laud anyone who funds them (with limits, Putin who is on the list of very bad people can forget about Western think tanks lauding him). But MbS did not deprive his opponents of ALL money and ALL friends, thus giving Khashoggi “Patkul treatment” (look up Johann Reinhold von Patkul) caused some hiccups.

So, on one hand MbS cooperates with “the good guys”, which makes him good, but then he treats “a good person” in a way that was somewhat disparaged even 300 years ago. That makes the balance close to zero, and thus requires actions that are close to nothing.

Amen to your article. It appears that our U. S. President is an opportunist? Shocking.

Quite! Just how bloody different is he than ANY previous occupant in that office….? Not all from this perspective…Hand out all the way.

Rat or slave

Open eyes and listen,

Yes you, you murderer,

Of course, you, Joe Biden.

Years ago, I wrote the

“Mutiny, Election.”

That was when Trump came,

Foresaw his arrival!

“He will win,” I confirmed,

“Not because of himself,

Only since the people,

Are tired, disgusted,

Of so much corruption!”

Result is visible,

In death of officer,

By Trump supporters!

Playing same old games?

Return to corruptions?

Think, enough are pranks,

Respect this given chance.

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

Months ago, in poem

Said what I say again:

“If you save murderer,

You become partners,

As leeches, vampires!”

You know that MBS,

Led brutal actions,

Of torture and murder!

You know he dismembered,

Used acid for solvent…

You know and know it well,

Let him go deep in hell.

Now, being some slave,

You mess and make mistake,

With same old dirty games…

What are we? Children?

You spoke with father?

You know if old man dies,

Next King is Mohammad!

We see same with Assange,

And bombing Syria…

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

Is this to teach lesson?

To Iran and others?

What about some manhood?

I see some defecate on your face!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

I warn you, Joe Biden!

Already are damaged,

These actions will further!

Be wise, make decisions.

Be caring and concerned,

Dignified with some sense.

The path you have chosen,

Is ugly, dangerous,

For the world and US,

For slaves and owners!

I don’t believe there ever was outrage.

Biden and Obama helped kill so many people, many hundreds of thousands, and create so many millions of refugees, I don’t see how outrage over one more death could possibly affect them.

And the truth is, we have learned nothing new about the murder.

From Turkey’s President Erdogan’s first revelations of the butchery with espionage recordings and photos, we really have known.

The people doing the grisly work were insiders, a privileged group in Saudi Arabia. There was no way the whole gang of them could just fly somewhere and kill someone without top-level authority.

Shortly later, Gina Haspel, Director of CIA, was reported to have told Trump the Crown Prince was responsible.

Stilt later, the truly sick Trump made a public joke about protecting the Crown Prince and being owed.

The hideous Crown Prince is central to the American Dark State’s intentions for the region.

No one was ever going to disturb that cozy, settled situation over the mere dismembering of a man while still alive, even a man with strong American connections.

The report means almost nothing.

America’s empire since WWII is a story gushing and dripping with blood – all the wars and coups and incursions and assassinations, none of them having anything to do with defense.

It has been estimated the US has killed 20 million through it all.

Joe Biden was around for nearly fifty years of that and supported everything.

Gee, he even got the Medal of Freedom, along with such American humanitarians as Madeleine Albright and Henry Kissinger.

Yep – such “humanitarians”….Gor Blimey, John, any culture, society that can consider Albright, Kissinger as “humanitarian” Obama, Biden as not murderous…and give at least two of those (well, Norway) “Nobel” Peace Prizes…is truly deficient in humanity, compunction, ethics, morals…Truly so…

Yep biden did say nothing was going to change and he has lived up to his word.

Yes, meet the new boss, same as the old boss.