As`ad AbuKhalil says the last two years have been calamitous for the country.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

All is not well in Lebanon. The last two years have been calamitous for the country and its people.

All is not well in Lebanon. The last two years have been calamitous for the country and its people.

First a severe financial crisis in 2019 wiped out billions in Lebanese deposits (most of the wealthy managed to transfer their fortunes out of the country at various phases before and after the crisis), and then a massive blast hit the Beirut port in August of last year, and severely damaged homes in half of the city. Coronavirus has only worsened the economic woes of the people.

The crisis is partly due to the corruption and mismanagement of the sectarian leaders who have ruled Lebanon since the end of the civil war in 1990. Sharing most of the blame are the late Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri who designed the financial system and began debt accumulation as well as Western-Gulf policies of strangulating Lebanon to exert pressure to disarm Hizbullah.

The aim of the economic strangulation of Lebanon is to secure Israel from any Lebanese right of self defense—in light of regular Israeli violations of Lebanese territory, space, and sea. Arab guarantees of the security and safety of Israeli occupation of Arab lands have been an impudent demand by the U.S. and Israel for decades.

Lebanese social and political divisions are not new; Mount Lebanon was split into two regions in the 19th century, and foreign powers invested heavily in Lebanese segmentation. By the 19th century, different sects had different foreign patrons.

Protests in Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square, Oct. 18, 2019. (Cyrusiithegreat, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Russia was the patron of the Greek Orthodox, Britain of the Druzes, France of the Maronites and other sects scrambled to keep a low profile hoping to avoid being dragged into a civil war.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire didn’t end the foreign patronage system; in fact, it merely accentuated it with the heavy-handed entry of Western powers into the Arab East. France colonized Lebanon after WWI and created what a League of Nations “Mandate system” — which was supposed to be a softer level of colonization leading to eventual independence in comparison to Western brutal control of Africa.

Declared a Country

France proclaimed Greater Lebanon (including parts of Syria) a republic in 1920. Syria became part of the French mandate in 1923. Lebanon gained nominal independence from France in 1943 (with French troops, which had repressed independence, withdrawing in 1946.) Syria became independent from the French mandate in 1946.

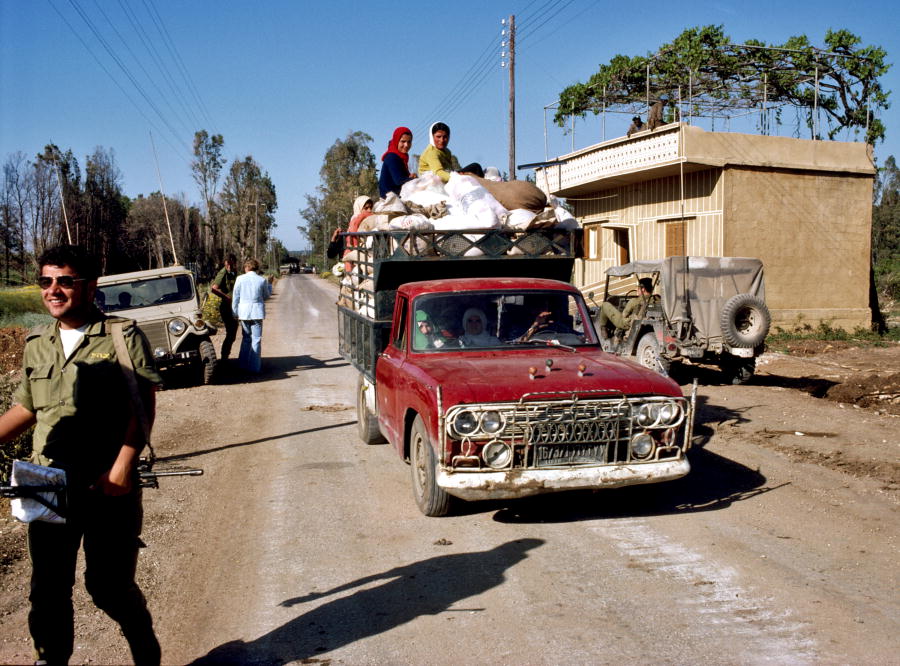

During the 1975-1989 civil Israel tried to tear the country apart by establishing in 1976 what it called “a buffer zone” in the south, a reference to a region it dominated with its army and a savage client militia, known as South Lebanon Army.

1978: Lebanese refugees entering the Israeli held town of Abbasiya after being cleared by Israeli soldiers. (UN Photo/John Isaac)

But Lebanon, as an entity, was not the product of a national will. The sects were not in agreement on the very creation of the country. Most Muslims (and many Christians and secularists) harbored aspirations of joining a larger Arab entity and they resented belonging to a political entity of political Maronite hegemony. (The hegemony favored the elite of the sect, and the elite of other sects also managed to profit from the system albeit in an inferior political position).

Gemayyel’s Partition Plan

Ideas about the partition of Lebanon were first floated early in the 1975-76 phase of the protracted civil war. The right-wing militia leader, Bashir Gemayyel and his allies, pursued the partition plan and were influenced by the Swiss canton system.

Right-wing figure, Musa Prince, of the Ahrar Party (headed by former president, Kamil Sham`un, whose insistence on extending his term in office in 1958 trigged a civil war), was the first to promote the idea of the cantonizaton of Lebanon.

Toward that vision, the right-wing militias of Gemayyel, led — with direct Israeli assistance — a campaign of sectarian and ethnic cleansing from all East Beirut regions. Palestinian refugee camps were razed to the ground, and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, Kurds and Muslims were evicted by force from the area through a series of massacres and military eviction raids.

The plan was to separate the predominantly Christian areas from the rest of Lebanon. The rival area (of West Beirut, the South and the mountains) maintained religious and sectarian diversity up until the Israeli invasion of 1982, which spawned various Islamist organizations that rejected the secular ideologies of either the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) or its ally, the Lebanese National Movement, which controlled West Beirut region and the South until the invasion.

The Lebanese Forces under Gemayyel tried to achieve complete independence from the rest of Lebanon; he established his own ports, his own army, his own media (he was about to launch his own TV station when TV broadcasting was a government monopoly), and was working to inaugurate a new airport before he was killed in September 1982.

He also tried in 1975-76 — but failed — to control the area in which the Central Bank was located. But the rise of Israel’s Likud Party in 1977 aborted his plans for partition. His patrons in Tel Aviv, especially Ariel Sharon, had other plans for Lebanon.

The PLO-Left alliance in Lebanon knew of Gemayyel’s partition plan and even tried in 1976 to defeat the Lebanese Forces and reunite the country, but the Syrian regime intervened in the spring of 1976 to prevent a PLO victory. Damascus did not want a radical change in Lebanon for fear of altering the quiet front with Israel in the occupied Golan Heights.

The Rise of Likud

The rise of the Likud raised Gemayyel’s ambitions. He started dreaming of controlling all of Lebanon through an Israeli invasion (the idea of making Gemayyel president was Sharon’s plan according to a transcript of a meeting between Bashir and Sharon, published in George Furayhah’s book, Ma`a Bashir).

The plan almost succeeded but Gemayyel was killed in September 1982, before assuming the presidency, and the Israeli occupation army was forced to humiliatingly withdraw (gradually) from Lebanon in the face of growing resistance movements. These included communists, nationalists and Islamists — Sunni and Shiite alike, although later Hizbullah emerged as the most effective group fighting Israel in Lebanon.

Hezbollah fighters on parade in Lebanon in undated photograph. (khamenei.ir, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Not since 1976 has Lebanon again faced the specter of partition. There is no single party or group calling for it today. But the financial collapse of 2019, and the decline of popularity and national legitimacy of sectarian zu`ama’ (political bosses), has changed politicians’ calculation.

The state treasury can’t no longer afford to provide patronage to political bosses to dispense with. The state is bankrupt and foreign benefactors are less generous and less interested in propping up traditional leaders.

Western governments and Gulf despots are now funding “civic groups” and new media. For that, each za`im is now focusing on his own constituency, trying to provide assistance to the community, but only at the local level, where one sect predominates.

This is taking place as political and sectarian polarization are at an all-time high: not only Sunni vs Shiite but also Christian vs Shiite, etc. Predominantly Christian areas (like Hadat and Kahhale) now openly advertise for home rentals and sales with the stipulation that buyers or renters must be Christian.

Sunni and Shiite tensions have never been more acute since the founding of modern Lebanon in 1920, and ideas of Christian separatism have emerged in the past few years. Lebanese Forces often speak about “self-security” in reference to their desire for private militias. Of course, militias never disappeared from Lebanon, they just went underground.

While those militias don’t have the heavy weapons they had during the civil war, they have managed to preserve enough arms to stand in a new civil conflict.

UN Interim Force in Lebanon on patrol, 2007 (UN Photo/Jorge)

In response to economic distress and repercussions of the Coronavirus, zu`ama have been distributing food aid packages to their local supporters. Regional hospitals are often run as a private possession of the local leader, and the state accommodates the needs of leaders for favoring their constituents even at the expense of the central government.

Some Christian leaders, like the Lebanese Forces, are now discussing the opening of another airport in predominantly Christian areas, and people in Tripoli have been calling for shifting the country’s main port to Tripoli from Beirut, in the wake of the Beirut port blast. Meanwhile, the Amal-Hizbullah alliance has tightened its grip on he South and the Biqa`, where the Shiite population is concentrated.

Political bosses do not seem worried about the prospect of partition. Druze leader Walid Jumblat is reverting to his old, civil war model, when he established his own sectarian canton, and named it “civil administration.”

The U.S. opposed partition back in 1975-76 according to declassified U.S. diplomatic dispatches and the partition scenario does not fit with U.S. interests because it will give South Lebanon total autonomy. The U.S. has invested in a heavy diplomatic, military, and intelligence presence in Lebanon and partition would jeopardize its plans.

The fragmentation of Lebanon would allow Hizbullah to roam more freely in South Lebanon and the ability of the state to maintain its army and security presence would diminish. Furthermore, the U.S. and UK are investing heavily in creating the Lebanese Army, not as an effective fighting force, but as a militia that answers to Western embassies in Beirut. They want the Army to extend its authority—on behalf of those Western patrons—all over Lebanon.

But the Lebanese population is suffering like never before from economic distress and the state is unable (due to its corruption, incompetence and bankruptcy) to aid the Lebanese. For that reason, it is easier for Lebanon’s political bosses to manage the affairs of each region on their own, with the help of immigrants from their sect.

Jumblat has been holding zoom conferences with American Druzes toward that effect. But Lebanese regions are not purely of one sect demographically. A mixture of sects is especially found in the capital. Because of that, partition plan could not be implemented peacefully.

Short of officially breaking up, Lebanon may descend into a de facto partition where the flag and national anthem remain as the last symbol of a once existent Lebanese “nation.”

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Lebanon Was No Accident

hXXps://youtu.be/YXOHVkLEkgo

Syria 7 months ago

hXXps://youtu.be/XKY4QcgxYTQ

“where the flag and national anthem remain as the last symbol of a once existent Lebanese “nation.”

kind of like the old #USofA then?

I appreciate the history and insights presented in this essay. As a Canadian I wonder how citizens of Lebanon are explaining their need to ‘leave’ a country and elderly family members’— to those they meet in their new ‘homes/countries’? As a citizen who has not even contemplated leaving my home country, I wonder why so many leave but never mentally leave, and the consequences they deal or don’t deal with—and the possible long term affects the new country may end up dealing with (but should never have-if not involved politically or militarily)?

Generally, I would suggest, that those who leave any and all of the so-called 3rd world countries, societies are almost always those who have been thoroughly westernized, usually via “International/American School” education then very often western university education. In other words they are the (mainly) Bourgeoisie…They feel, understand zero cultural, social connection to their working class, poor compatriots, who more often than not, are more religiously adherent, more linked to their ancient, long lasting heritage, culture than the very comfortably off….And the latter seek emigration to the west because, hey, the west offers nice salaries, money making ops, while helping those lower, much lower down the ladder in your culture, society of origin cannot do so…so let them (those in lower socio-economic levels) live with it…

Are you saying people leaving Lebanon are bringing with them to their ‘new’ countries the sectarian tensions of their ‘old’ country? That’s what it sounds like. Canada has many problems but emigrants from Lebanon destabilizing the country’s social fabric isn’t one of them.

It’s easy to proclaim that you’ve never even thought of leaving your country of birth when you live in a peaceful, stable and reasonably prosperous nation. You might see things differently if you had to deal with violence, war and severe economic deprivation on a regular basis.

That said, most people do not leave their home countries even when conditions are bad. They have no desire to leave in the first place or they are unable to afford to leave. The issue you are raising here is a massive straw man.

If you are genuinely concerned about the plight of Lebanon and its people you might want to consider how your country, Canada, unfailingly supports the many nefarious ways the United States, Israel and the GCC states undermine Lebanon and collectively punish its population in a bid to undermine Iran and Hezbollah.

Great comment

Reunite with Syria!

Especially Southern Lebanon…Without Hizbullah, Lebanon would have grabbed by guess who????

Thanks for the history lesson

Another brilliant and objective analysis by Professor AbuKhalil. I can only hope his views reach wider circulation and consideration.

Outside interests own and control the north of Lebanon, but cannot get control of the South along Israel’s border. The dividing line is basically along the old line of 20 years of Israeli occupation of Lebanon.

If it partitions, then Israel and the US would lose the last control they’ve got over the part they care about most, along the Israeli border. So they won’t let it partition.

Whose country is it? Who gets to decide what partitions?

~

If anybody is first in line, I’m guessing it is the citizens of the country.

~

Does somebody have a better idea or does somebody else get to be the “decider”?

~

Those are all very serious questions that also deserve consideration.

~

I think the answers are kindergarten simple, so what the hell, I’ll answer one of them.

~

It is up to the citizens of the country to decide their own fate.

Not the business of the US or their close human rights’ abuser colleagues and $ beneficiaries, the OAP (Occupiers of All Palestine)..And more much more power to Hizbullah’s elbows…