Part of the work is going back to go forward, writes Vijay Prashad. Returning to the sources of tradition advances present struggles.

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

In 2011, the Swedish novelist Henning Mankell travelled to India to deliver the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Lecture in New Delhi. Mankell recounted an incident from Mozambique, where he lived for part of each year.

In 2011, the Swedish novelist Henning Mankell travelled to India to deliver the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Lecture in New Delhi. Mankell recounted an incident from Mozambique, where he lived for part of each year.

In the 1980s, after Mozambique won its independence from Portugal in 1974, the South African apartheid regime and the settler-colonial army of Rhodesia backed an anti-communist faction against the government of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). The point of the war was to destroy the bases of the South African and Zimbabwean national liberation forces that had been given permission to operate by Mozambique’s FRELIMO government.

The war imposed on Mozambique was brutal, the destruction immense. Mankell visited a border region, where the invading troops and their anti-communist allies had burnt down villages. He was walking on a path towards a village. He saw a young man coming towards him, a thin man in ragged clothes.

As he came close, Mankell saw his feet. “He had in his deep misery,” Mankell told his Delhi audience, “painted shoes on his feet. In a way, to defend his dignity when everything was lost, he had found the colours from the earth, from herbs, and he had painted shoes on his feet.”

For Mankell, this man’s act was a form of resistance against the fading light of hope; although this man could very well have been on the way to a meeting of his FRELIMO branch, where they would discuss the current situation of their struggle and plan to defend their land.

In 1981, when South Africa attacked Mozambique, President Samora Machel of FRELIMO embraced Oliver Tambo of South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) at a public rally in Maputo’s Independence Square and said, “We don’t want war. We are peacemakers because we are socialists. One side wants peace, and the other wants war. What do we do? We let South Africa choose. We are not afraid of war.” These might have been the words that rang in the ears of the man that Mankell had seen.

During the national liberation struggle, Machel had said that the revolutionary process was not only about victory over the Portuguese — or the South African apartheid state or the Rhodesian settler-colonial state — but it was about the “creation of a new human, with a new mentality.” It was that struggle against colonialism that produced a society where people were proud, even if they did not, as yet, have necessary goods, such as shoes.

The Struggle for Dignity

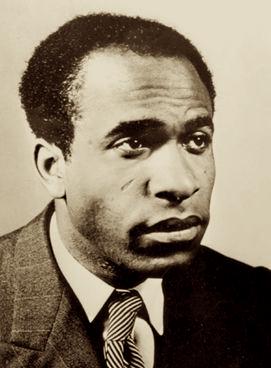

Frantz Fanon. (Wikimedia Commons)

The struggle for dignity is elemental, and it formed a core part of the ideology of national liberation. This was the premise of the work of two thinkers — Frantz Fanon and Paulo Freire — whose writings emerged out of the national liberation and socialist traditions, which impacted those struggles in turn.

It is no surprise that our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research office in Johannesburg (South Africa) has produced two dossiers on these two important figures: Frantz Fanon: The Brightness of Metal in March 2020, and now Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa in November 2020.

Part of our work in the Institute is to go back to go forward; to return to the sources of our tradition, study them carefully for their important lessons, and then draw from them in order to advance our struggles in the present. Both Fanon and Freire — the latter influenced by the former’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961) as he drafted his classic Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) — emphasized the importance of collective study and struggle as the lever to develop a critical consciousness amongst the masses.

Their general orientation towards the integral relationship between collective study and struggle informs our own approach in the Institute, as we laid out in our dossier The New Intellectual in February 2019.

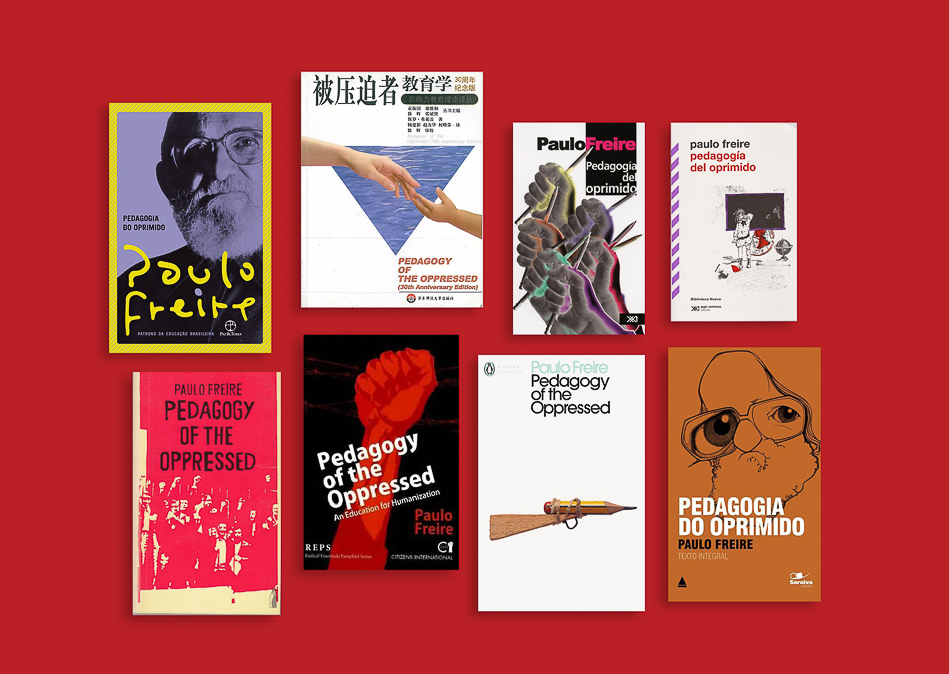

Book covers of Pedagogy of the Oppressed in different languages.

Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed was written while the Brazilian intellectual was in exile in Chile, where he had fled after having spent 70 days in a Brazilian prison during the early days of the U.S.-backed military coup of 1964. For the book, Freire drew not only from his own experience in the struggles in Brazil, but also from what he had read about the Algerian liberation movement (via Fanon) and from his engagement with the national liberation movements in Portuguese-colonized parts of Africa.

The oppressed, Freire wrote, did not want knowledge for its own sake; they expressed a range of desires for the world, including to create a world where they could live with dignity, including with shoes. Freire quotes Che Guevara’s powerful sentiment that “a true revolutionary is guided by strong feelings of love,” which forms the bedrock of Freire’s approach.

“The revolution loves and creates life,” Freire wrote, “and in order to create life it may be obliged to prevent some men from circumscribing life.” This was not “love” in the abstract but love in a very concrete way.

In Brazil, Freire wrote, there were “living corpses” or “shadows of human beings” who faced an “invisible war” of hunger and disease, illiteracy and indignity; their liberation from the structural domination of capitalism would require the defeat of the actual people who benefitted from the system which deprived the oppressed of basic needs.

The rising of the oppressed — in other words, the Revolution — was going to improve the life of the vast majority, but it would necessarily negatively impact the lives of the capitalists. There was no idealism in Freire — only the deeply practical appreciation of study and struggle within the actual world in which we live.

Paolo Freire in 1963. (Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons)

It is perhaps Freire’s firm grip on the actual processes of social life that influenced generations of South African freedom fighters. Our latest dossier, Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa, documents the influence of Freire’s ideas within the Black Consciousness Movement, the church, the workers’ movement, and in the heart of the liberation struggle.

In an interview for this dossier, Aubrey Mokoape, who founded the South African Students Organisation in 1968 along with Steve Biko, Barney Pityana and others, told Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research how Freire’s idea of “conscientization” advanced the socialist agenda of the Black Consciousness Movement:

“The only way to overthrow this government is to get the mass of our people understanding what we want to do and owning the process, in other words, becoming conscious of their position in society, in other words … joining the dots, understanding that if you don’t have money to pay … for your child’s school fees, fees at medical school, you do not have adequate housing, you have poor transport, how those things all form a single continuum; that all those things are actually connected. They are embedded in the system, that your position in society is not isolated but it is systemic.”

To live with dignity and with love would mean to transform a system that is incapable of solving the problems it creates. Education — or “conscientization” — is precisely about the interrelated process of study and struggle in forming a consciousness and a conscience that demands more than moderate reforms. It was not about being given shoes but fighting for a system where a lack of shoes cannot even be imagined.

Mongane Wally Serote, second from left; Nadine Gordimer, center; and Dennis Brutus, second from the right. (Courtesy of Amazwi South African Museum of Literature)

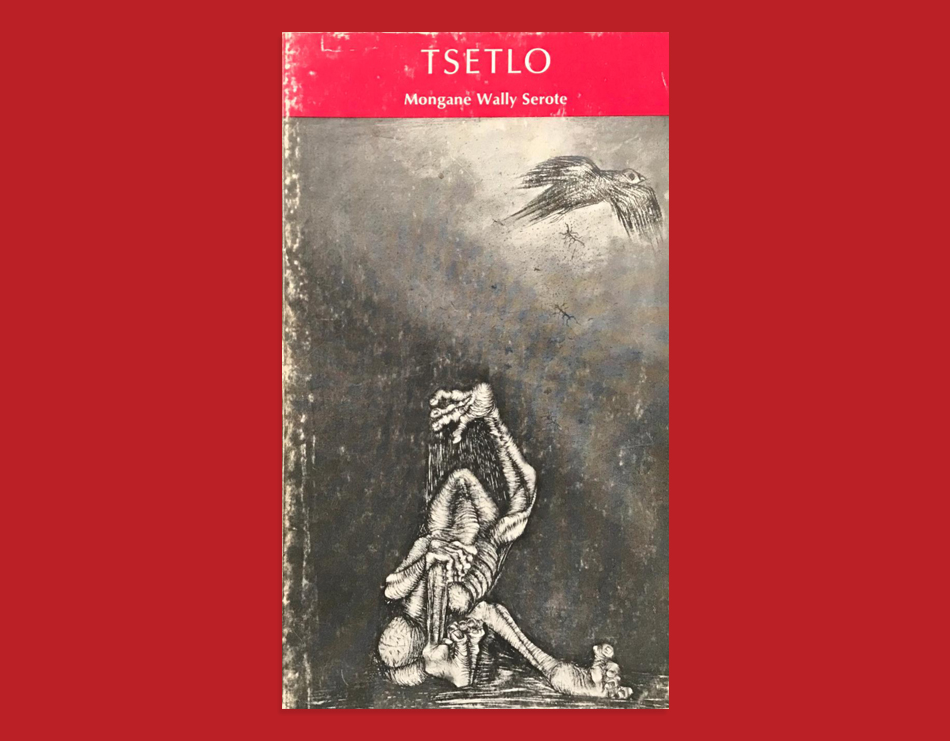

South Africa’s poet laureate Mongane Wally Serote underwent “conscientization” in the Black Consciousness Movement during his school years in Soweto, before he joined the African National Congress. In 1969, Serote was arrested and spent nine months in solitary confinement. He eventually went into exile: first to Botswana, where he joined the uMkhonto weSizwe, the military wing of the ANC, and then formed the Medu Arts Ensemble with Thami Mnyele and others. Later, Serote would go to London to work in the ANC’s Department of Arts and Culture. He returned to South Africa in 1990.

In 1977, Serote and others formed the Pelandaba Cultural Effort in Gaborone (Botswana) and published Pelculef. In the first issue of the journal, published in October 1977, Serote published his poem no more strangers. The rhythm of the poem is the pulse of the struggle to which Serote and his comrades had dedicated their lives. Here’s a brief extract, the impression of Freire’s ‘conscientisation’ imprinted in it:

it were us, it is us

the children of Soweto

langa, kagiso, alexandra, gugulethu and nyanga

us

a people with a long history of resistance

us

who will dare the mighty

for it is freedom, only freedom which can quench our thirst —

we did learn from terror that it is us who will seize history

our freedom.

…

remember the shattering despair to feel as worthless as debris

remember the shades of death we longed for

here we are now

…

it will be us

steel-taut to fetch freedom

and —

we will tell freedom

we are no more strangers now.

Cover by Thami Mnyele for Tsetlo by Mongane Wally Serote, 1974.

It has to be us. We are waiting for no-one else. It can only be us. We will make our own shoes. It will be us. We will walk with dignity. We will prevail.

Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian, journalist and commentator, is the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the chief editor of Left Word Books.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ Winter Fund Drive

I found this article very interesting as my sister was involved in all those events in Moçambique and South Africa. She married a Portuguese Moçambquan (?), an engineer, Armando.

When the revolution came – the independence of Moçambique from Portugal – she and her husband were on opposite sides; my sister on that of Samora Machel and her husband got involved in a putsch attempt to reimpose something like colonial power. Armando was jailed and was, I believe, on death row. If I am not mistaken, my sister knew Machel personally and wrote to him to plea for her husband’s life. My sister and I went to Amnesty International in Paris for the same reason.

Then came that historical moment when the so-called communist regimes decided that they needed the know-how of the capitalist world. Armando was released from prison and given comfortable accomodation in a hotel so as to continue his work as an engineer.

My sister had a tough time in Moçambique despite her support of Frelimo and at some point had to escape to South Africa where she sympathised with the ANC.