Declassified files show that Britain conducted a covert propaganda offensive to stop Allende from winning two democratic presidential elections, John McEvoy reports.

Chilean workers marching in 1964 to support electing Salvador Allende as president. (James N. Wallace, U.S. Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)

By John McEvoy

Declassified UK

Almost 50 years after the September 1973 coup that overthrew the democratically-elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, declassified Foreign Office documents reveal Britain’s role in destabilising the country.

Almost 50 years after the September 1973 coup that overthrew the democratically-elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, declassified Foreign Office documents reveal Britain’s role in destabilising the country.

Under the Labour government of Harold Wilson (1964-1970), a secret Foreign Office unit initiated a propaganda offensive in Chile aiming to prevent Allende, Chile’s leading socialist figure, winning power in two presidential elections, in 1964 and 1970.

The unit – the Information Research Department (IRD) – gathered information designed to damage Allende and lend legitimacy to his political opponents, and distributed material to influential figures within Chilean society.

The IRD also shared intelligence about left-wing activity in the country with the U.S. government. British officials in Santiago assisted a CIA-funded media organization which was part of extensive U.S. covert action to overthrow Allende, culminating in the 1973 coup.

Anyone but Allende

A Foreign Office planning document written in 1964 had noted that Latin America was “a vital area in the Cold War and checking a Communist takeover here is at least as important a British national interest as negotiating trading and stepping up exports.”

The report added that the U.S. was “anxious for the United Kingdom to do as much as possible in the propaganda field” in Latin America.

Several months before Chile’s 1964 presidential election, a British Cabinet Office unit called the Counter-subversion Committee’s Working Group on Latin America, advised the IRD that “it will be important to prevent significant gains by the extreme left” in Chile, “now and later”.

At this time, Allende was a presidential candidate in the election running as leader of the Frente de Acción Popular (Popular Action Front) against the Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei, who eventually won with 56 percent of the vote against Allende’s 39 percent.

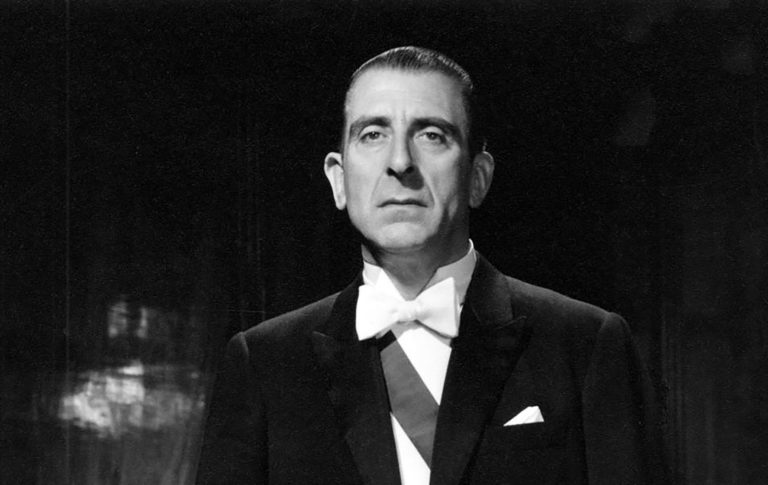

Eduardo Frei was president of Chile from 1964-70. (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, Creative Commons)

The IRD initiated its propaganda offensive in Chile by covertly supporting Frei in the months leading up to the election. As Elizabeth Allott, a longstanding IRD officer, wrote shortly after Frei claimed victory, the unit had focused on “the distribution of our more serious material to reliable contacts and to securing the publication of certain press articles” critical of Allende, and favourable to Frei.

Allott had also proposed “SPA [special political action] with supporting action from the U.S.” to split the left vote.

British planners viewed the 1964 election as a landmark success. “In Chile we surely have a rare opportunity,” wrote Allott: “If we believe our work in Latin America to be important, then there are surely few places which have a better claim on our resources and where there is such scope for us in both our negative and constructive roles.”

Leslie Glass, assistant under-secretary for foreign affairs and former director-general of British Information Services, agreed. Writing days after the election, he noted that this was “a victory against the communists to press home” adding that there was now “a government to support whose policies, if carried out effectively, offer what is probably the best chance we have had in the continent of robbing the communists of their raison d’être.”

Frei ruled Chile for the following six years until the country went to the polls again in 1970. By this time, Allende was leader of a coalition grouping known as Popular Unidad (Popular Unity), which pledged to redistribute economic power in Chile.

Allende’s platform proposed to transform “the present economic structure, doing away with the power of foreign and national monopoly capital and of the latifundio [large agricultural estates] in order to initiate the construction of socialism.”

Allende’s policies of nationalisation posed a considerable threat to British and U.S. interests, particularly in Chile’s major industry, copper, whose mines were substantially owned by U.S. companies.

Chuquicamata, a state-owned copper mine in Chile, in 2016. By excavated volume it is the largest open pit copper mine in the world. (Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

As Allende looked increasingly likely to win power, British propaganda operations intensified. “Chile is in the front line as far as communism in South America is concerned,” one IRD planner noted in 1969.

The IRD deployed a specialist field officer to Santiago during the late 1960s, whose operations focused directly on thwarting an Allende victory.

At the same time, the Foreign Office dispatched a labour attaché to Chile in order to monitor trade union activity, although the attaché was withdrawn before the 1970 election.

On 13 July 1970, with just weeks until the election, Allott informed British Ambassador David Hildyard that “the IRD operation… has been concentrating on preventing an extreme left alliance from gaining power in the 1970 presidential elections, and on helping suitable organisations which are likely to continue in existence whatever happens at the elections.”

She added: “The IRD field officer… has very close contacts with specialist officials in the [Chilean] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, [redacted], and certain student organisations. As elsewhere in Latin America we can cover areas closed to the Americans.”

Allott also proposed to IRD chief Kenneth Crook that Britain train the Chilean military in “counter-subversion.” Notably, she referred to Britain’s previous training of the Brazilian dictatorship’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was later revealed to include lessons in torture techniques.

British efforts to stop Allende failed, and the Chilean presidential election in September 1970 brought to power the country’s first avowed socialist ever elected to office.

The Washington Connection

British covert action in Chile was undertaken in collaboration with the U.S., whose role in destabilising the country has emerged in the decades since. Between 1962 and 1970, the CIA “undertook various propaganda activities” including “placements” of material “in radio and news media” in support of Frei and against Allende.

It also organised “spoiling operations” against Allende and engaged in a three-year campaign between 1970 and 1973 to politically “assassinate” him by funnelling “millions of dollars to strengthen opposition political parties”, according to a U.S. Senate report.

IRD files show how, during the late 1960s, British planners shared strategic advice and intelligence with U.S. officials. Though IRD planners cautioned the U.S. against “possibly taking a too extreme line” in its anti-communist propaganda, they nonetheless provided U.S. officers with a list of Chilean journalists who could produce desirable content.

The U.K. and U.S. also shared information on left-wing activity in Chile, an arrangement which continued until at least March 1973, the declassified British files show.

Allende was overthrown in a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, the head of the Chilean military, on 11 September 1973, to widespread international condemnation. His regime quickly became one of Latin America’s most repressive in modern history as thousands of political opponents were herded into Chile’s national football stadium or secret detention centres.

Salvador Allende in 1972. (Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons)

Alongside much more extensive U.S. covert action, British officials played a covert role in preparing the ground for Pinochet’s takeover in alliance with the U.S.

In October 1970, British officers in Santiago had covertly facilitated a CIA-funded news agency, Forum World Features (FWF), “to arrange for special coverage of the Chilean situation.” One month after Allende’s election, British Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home had instructed the embassy in Santiago to “respond to any approach” from FWF after its chief, Brian Crozier, requested assistance for a series of “behind the scenes” articles on Allende’s programme.

FWF played a significant role in the propaganda onslaught against Allende. In December 1973, three months after Pinochet’s coup, FWF journalist Robert Moss published Chile’s Marxist Experiment – a CIA-commissioned book which denied Washington’s role in the coup, and laid the blame at the feet of Allende.

The Pinochet regime purchased 10,000 copies of the book “to be given away as part of a propaganda package” and Crozier later recalled that Moss’ work “played its part in the necessary destabilisation of the Allende regime.”

Foreign Office official Hugh Carless agreed, writing in December 1973 that the book “helped us to strike a balance” on Chile.

Rory Cormac, professor of international relations at the University of Nottingham, told Declassified: “These recently declassified documents are significant because they reveal British special political action outside of traditional areas of priority. As its material capabilities declined, Britain turned to covert action to help maintain its global role.”

Pinochet: ‘Staunch, True Friend’ of Britain

General Augusto Pinochet in 1982 motorcade. (Ben2, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Conservative government under Edward Heath (1970-74) rushed to give diplomatic recognition to Pinochet’s new regime. Foreign Office files show that British planners in Santiago and London immediately set about conducting good relations with the military rulers as their repression increased.

By 1974, and under public pressure due to Pinochet’s human rights abuses, the Wilson government, which had returned to power, applied sanctions on Chile, involving an arms embargo and the removal of the British ambassador in Santiago. These were continued by the subsequent Labour government under James Callaghan.

After Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979, however, Britain resumed friendly relations with Chile, selling arms that could be used for internal repression while training hundreds of Chilean soldiers. Thatcher went on to call Pinochet a “staunch, true friend” of Britain.

After the fall of Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1990, a truth commission confirmed that during his 17-year rule more than 40,000 people were tortured, 3,200 were killed or “disappeared” and more than 200,000 fled into exile.

Though Labour and Conservative policy differed towards Pinochet, the recently declassified record sheds a new light on the claim that Labour sought to promote an ethical foreign policy towards Chile. It was under Wilson’s first administration that Britain’s covert propaganda offensive against Allende began.

British officials not only welcomed Chile’s dictatorship in 1973 – they spent a decade helping to create the conditions that brought it to power, and played a material role in destroying Chilean democracy for a generation.

John McEvoy is an independent journalist who has written for International History Review, The Canary, Tribune Magazine, Jacobin, and Brasil Wire.

This article is from Declassified UK, an investigative journalism organisation that covers the UK’s role in the world. Follow Declassified on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Sign up to receive Declassified’s monthly newsletter here.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’

25th Anniversary Fall Fund Drive

Donate securely with

Click on ‘Return to PayPal’ here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Show Comments