We have returned to Franklin Roosevelt’s one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished, writes John Buell.

What does it mean to have wealth approaching six-figure billions? Sen. Everett Dirksen once famously quipped “a billion here and a billion there and pretty soon you are talking real money.” I think it is helpful to translate these highly abstract big numbers into the real goods and services one could command with this money.

A state-of-the-art naval destroyer costs about one billion, about the cost of an NBA franchise. One can add a few luxury homes and still have spent only a small fraction of one’s wealth. Clearly possession of an ever-growing stream of goods seems to be an unlikely motivator of the mega wealthy.

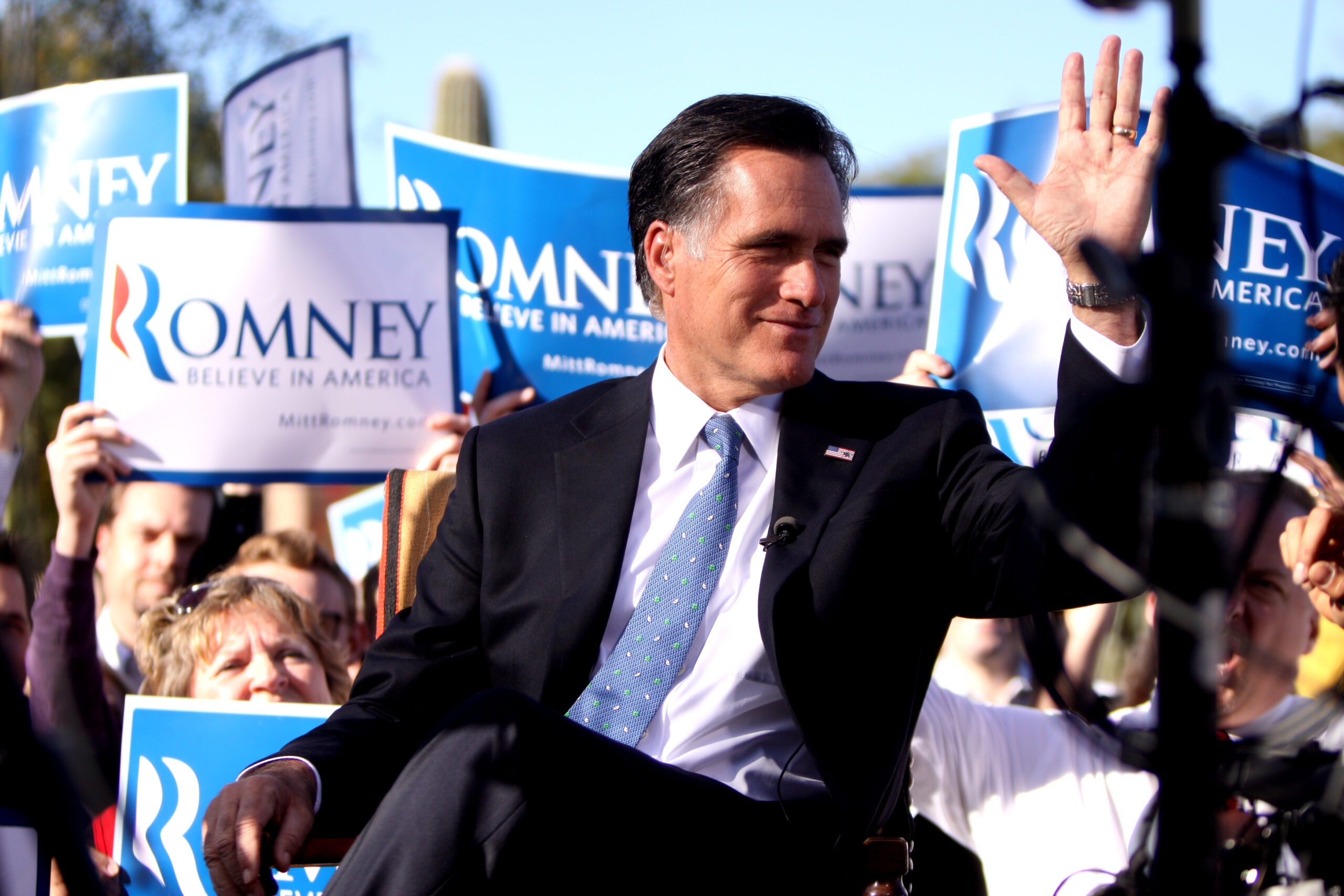

Even Thorstein Veblen’s notion of conspicuous consumption must confront the fact that there are only so many hours in a day and thus limits to what can display. In this regard, I am always amused by Mitt Romney’s inability in the course of a presidential debate to remember how many houses he owned.

Former Gov. Mitt Romney at a presidential campaign rally in Paradise Valley, Arizona, December 2011. (Gage Skidmore, Flickr)

If unfathomable levels of wealth are often sought for something other than mere possession, what is the motivation and are these billionaires justified in the steps taken to these acquisitions?

Conventional economics construes great wealth as the market’s reward for patient investment in those goods and services that most benefit society. And the same market that bestows rewards on the skilled and innovative shows no mercy to those who squander vast resources on overly ambitious or misjudged schemes.

Adam Smith, generally regarded as the father of market economics, had a more jaundiced view of the origins of great wealth: “People of the same trade seldom meet together but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public or in some diversion to raise prices.” Or as Balzac famously put it, “behind every great fortune lies an equally great crime.”

Those attentive to recent news from D.C. could provide Smith some current examples of anti-competitive maneuvers. Antitrust activist Sarah Miller cites the tech giants as blatant and unashamed practitioners of this strategy.

Bezos describes his strategy similarly, asserting that “the stronger our market leadership, the more powerful our economic model…we will make bold rather than timid investment decisions where we see a sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages.” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has conveyed the same approach, but more to-the-point; for many years, he allegedly ended staff meetings shouting, “Domination!”

Miller concludes, “The best way to get astronomically rich in America is to acquire monopoly power to extract wealth from workers, consumers, entrepreneurs, small businesses, and, through tax breaks, subsidies, and contracts, our government itself. Monopolies are powerful generators of the inequality that progressives decry.”

Packing food boxes at a Covid response warehouse, April 23, 2020 in Seattle. (Air National Guard, Tim Chacon)

During the pandemic, as during the world finance crisis, power has been both the means and the end of domestic and international economic policy. During the early stages of the global economic crisis, government responded by creating a $700 billion facility to purchase troubled assets from banks, but only about 10 percent of these expenditures went to lowering mortgage interest rates.

Federal Reserve treatment of the big finance center banks was much more generous. It lowered the interest rate charged member banks to near zero, a figure it held for almost a decade. The effects of this policy were not neutral.

Lower rates in the financial sector were supposed to encourage new investment in the real economy but instead did little more than stimulate a bull market in stocks and cheap money to finance stock buybacks and leveraged mergers and acquisitions. (Yves Smith , founder of the blog Naked Capitalism, points out that the only industry for which cheap money is a resource that might encourage further investment is finance. So much for restoring the productivity of main street.)

Monopoly power and concentrated wealth do immense harm to the bottom third of the wealth spectrum. We have returned to Franklin Roosevelt’s one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished. Late last year The Los Angeles Times reported:

“New research establishes that after decades of living longer and longer lives, Americans are dying earlier, cut down increasingly in the prime of life by drug overdoses, suicides, and diseases such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, and obesity… the authors of the new study suggest that the nation’s lifespan reversal is being driven by diseases linked to social and economic privation, a healthcare system with glaring gaps and blind spots, and profound psychological distress.”

The moral case for egalitarian reforms is overwhelming. Obscene wealth disparities are a product of political and economic power, not virtue or extraordinary talent. On the center Left the most popular proposals are various versions of a wealth tax. Such proposals should surely be part of any reform package.

A wealth tax would begin to redress the damage inflicted by four decades of socialism for the rich. And it should be framed that way in order to counter in advance the inevitable carping that tax reformers are motivated by envy. Nonetheless more needs to be promoted in order to address the causes as well as consequences of this inordinate wealth concentration.

Miller correctly argues: “Trying to address wealth inequality without addressing monopoly power is like trying to stop a boat with a hole in the bottom from sinking by bailing out the water, but not plugging up the hole.” She emphasizes the role that a reinvigorated antitrust policy that attacked the anti-democratic and anti-competitive aspects of economic concentration.

I would advocate, in addition, policies that give working-class citizens more voice in designing the economic instruments that will produce future wealth for us all. Antitrust law, cooperatives, labor rights to organize, and democratization of the Fed would all be parts of such reform packages.

John Buell has a PhD in political science, taught for 10 years at College of the Atlantic, and was an associate editor of The Progressive for 10 years. He lives in Southwest Harbor, Maine, and writes on labor and environmental issues. His most recent book, published by Palgrave in August 2011, is “Politics, Religion, and Culture in an Anxious Age.” He may be reached at jbuell@acadia.net

This article is from

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News

on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Show Comments