Vijay Prashad raises deep questions about the exhaustion of the global capitalist system in a time of great human suffering.

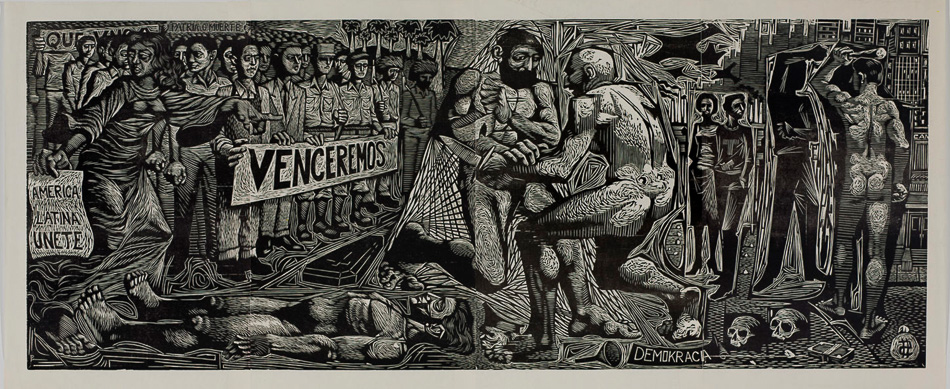

Luis Peñalver Collazo (Cuba), America Latina, Unete! 1960.

Here Not Death but a Frightful Future

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has released its June 2020 update. The prognosis is bleak. Global growth for 2020 is projected at -4.9 percent, 1.9 percent below the IMF’s forecast from April. “The Covid-19 pandemic has had a more negative impact on activity in the first half of 2020 than anticipated,” acknowledges the IMF.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has released its June 2020 update. The prognosis is bleak. Global growth for 2020 is projected at -4.9 percent, 1.9 percent below the IMF’s forecast from April. “The Covid-19 pandemic has had a more negative impact on activity in the first half of 2020 than anticipated,” acknowledges the IMF.

Forecasts for 2021 are somewhat optimistic, sitting at 5.4 percent, which is higher than the 3.4 percent the IMF predicted in January 2020.

“The adverse impact on low-income households is particularly acute,” says the IMF. Poverty reduction is effectively off the agenda. The World Bank’s recent report takes a dim view, with 2020 growth forecast at -5.2 percent, predicting the deepest global recession in eight decades. The World Bank’s expectation of growth for 2021 is at 4.2 percent, lower than the IMF’s 5.4 percent prediction.

This is the season of annual reports, and each one of them seems to be more depressing than the other. The IMF had earlier called the world economic situation the “Great Lockdown;” now, in, their new report, the Bank of International Settlements calls it a “global sudden stop.” Either way, they indicate the convulsion of large parts of the world economy.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) had predicted a 32 percent decline in global trade volume, but it now seems to have only fallen by 3 percent (global commercial flights decreased by 74 percent from January to mid-April and have since risen by 58 percent as of mid-June, while container port traffic has recovered in June as compared to May). “It could have been much worse,” says WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo.

Dikó, Cacri Photos (Venezuela), Chess in the time of COVID, Caracas, 2020.

The International Labour Organisation cannot be as glib; the situation is as bad as predicted, or even worse. In a concept note for a conference in early July on Covid-19 and the world of work, the ILO says that the pandemic has resulted in the loss of at least 305 million jobs, with the impact slowly but surely striking the Americas.

This is a conservative figure; a more radical number is that half of working-age people are without adequate income. The ILO writes that, in terms of work, the virus “has hit the most disadvantaged and vulnerable in the hardest and cruelest way, so exposing the devastating consequences of inequalities.”

Two billion workers are in the informal economy (six out of 10 working people); of them, the ILO report notes, 1.6 billion “face an imminent threat to their livelihoods as average income in the informal economy shrank by 60 percent in the first month of the pandemic. That has brought a dramatic increase in poverty, and the warning from the World Food Programme in April that the next pandemic could be a “pandemic of hunger,” a topic we have approached in our 20th newsletter of this year.

Shoppers pay to be disinfected at Rodríguez Market, La Paz, Bolivia, 2020. (Carlos Fiengo)

The unequal negative impact of the coronavirus recession needs to be foregrounded. In a recent interview, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said that a 3.2 percent contraction of the economies in Africa would be “the heaviest hit on Africa at least since the 1970s.”

South Africa’s economy had already begun to contract before the pandemic and is now in dire straits; Minister of Finance Tito Mboweni said that it would likely contract by more than 7.2 percent in 2020, the country’s most significant downturn in a hundred years. As an antidote, Mboweni has chosen the path of austerity, which, economist Duma Gqubule writes in New Frame, “will result in collapsing public services and rising levels of unemployment, poverty, and inequality that will turn the country into an economic wasteland.”

‘Can’t Breathe’

Faced with pressure from the IMF and from international creditors, Ghana’s Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta said that while the rich countries were being permitted to grow debt to stimulate the economy, countries like Ghana were being told to stick to the rules, make their debt servicing payments, and drive an austerity agenda. “You really feel like shouting: ‘I can’t breathe,’ Ofori-Atta said, deliberately echoing the last words of George Floyd.

Debt cancellation, such a fundamental issue for our time, is simply not on the agenda. In fact, the U.S. Department of the Treasury has made it clear to the IMF that even the issuance of $1 trillion in special drawing rights (SDRs) to provide funds to cash-starved states hit by the coronavirus recession would not be possible. The U.S. Treasury has also made it clear that debt relief is a private-sector matter that should be left to the creditors. No wonder that Ofori-Atta used the highly charged expression “I can’t breathe” to indicate the suffocation of the economies and people in the Global South.

Herb and spice vendor, La Paz, Bolivia, 2020. (Carlos Fiengo)

Carlos Felipe Jaramillo, the Colombian economist and recently appointed World Bank vice president for the Latin America and the Caribbean, said that the region would likely lose 20 years of advances in poverty alleviation, with at least an additional 53 million people being driven into poverty. Latin America, he said, faces “its worst crisis since [modern] record-keeping began, at least 120 years or so ago.”

What Jaramillo says here is amplified with clarity by a new dossier from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research: “Latin America Under CoronaShock.” This dossier, prepared by our offices in Buenos Aires (Argentina) and São Paulo (Brazil), offers a comprehensive analysis of the health, social, and economic crises in the region.

Drawing on data from the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, the dossier shows that unemployment, poverty, and hunger will escalate out of control in the region. The IMF has said that Latin America might recover a growth rate of 3.7 percent in 2021, but even this is premised upon the stabilization of the pandemic and the return of higher commodity prices, neither of which are on the horizon.

Crucial to our dossier is the idea that any policy framework that is on the table now is merely repackaged neoliberalism (as is evident in Jaramillo’s insistence on Latin America’s need to “foster innovation and entrepreneurship and competition to address low productivity,” when the problem is an employment and hunger crisis of a magnitude that goes beyond Jaramillo’s empty verbiage and that is in fact largely a result of the kind of policies that he proposes).

In a previous study in June, (“Nuestra América bajo la expansión de la pandemia”) our office in Buenos Aires pointed out that the economic contraction that is taking place in Latin America cannot be reversed without a better monetary policy (rather than through cycles of devaluation) and the cancellation of debt (which in Argentina approaches 100 percent of the GDP).

Despite the crisis revealed by the pandemic, political forces that are wedded to the religion of neoliberalism continue to read from its catechism: austerity, sound money, deregulated capital markets, balanced budgets, privatization, and liberalized trade. For this reason, our dossier argues, governments in the region remain trapped within a neoliberal policy framework, which gives priority to “protecting the economy before protecting the people.”

There are Hungry and There is Food

To protect the economy is another way of saying to protect the idea of private property. There are hungry people, and there is food, and yet the food is not delivered to the hungry because they do not have money and because food is treated as a commodity rather than a right. Governments prefer to use social wealth to hire military and police forces to keep the people away from the food, a sure sign that the system has a desiccated soul.

Our dossier, although based on material from Latin America, raises deep questions about the exhaustion of the global capitalist system in a time of great human suffering; neither neofascist nor neoliberal governments, which uphold the capitalist logic of property over human needs, are capable of managing the scale of the human catastrophe that they in part created.

The pandemic and its impact: the Brasil de Fato interview, 2020 (in English with Portuguese subtitles)

Recently, the Brazilian media portal Brasil de Fato interviewed me about the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research studies on CoronaShock and on the post-Covid-19 landscape. In the interview, I summarize the work of our institute, especially of the impact of the pandemic on the developing world.

It is impossible to imagine that the miserable situation now will not be overturned by the capacity of human beings to find ways to gather together and transform our reality. This is not something theoretical. Already our popular movements are forging ways to provide relief and to push for alternative futures. The rot exposed by the pandemic augurs a future that is frightening. That is, unless we decide to take it into our hands to shape the world that we want to live in.

Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian, journalist and commentator, is the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the chief editor of Left Word Books.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium

News on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Any economic system based on scarce money will create an imbalance of wealth and amplify that maldistributed wealth like an amplifier with positive feedback until something breaks. It also provides the greatest rewards to psychopaths, who work tirelessly for wealth & power, without any conscience or human considerations.

We need a better system. We need to develop an economy that doesn’t lead to “Nice people finish last.” We all need to finish together.

The US military budget that assists the USA in maintaining world dominance, stands in stark contrast to the cash strapped IMF. Why can’t the USA ask China to forgive some of our debt in exchange for help? I really don’t know how realistic this is.

You want China to help the USA put more money into “defense” and illegal sanctions???

I don’t think China needs help from the U.S. Why doesn’t the U.S. lower it’s military spending and elevate the people?

That is the most wonderful film I have seen in a very long while! Hardly surprising from Vijay Prashad and very welcome. I recommend this to everyone!!!!

We need to rethink our whole existence since this pandemic, and try to get some benefit for the future for the MAJORITY of the people, not the few.

Indeed Rosemerry – the world needs to become non-neoliberal-non-capitalist, needs to cease the worship of and to Mammon and Moloch (the latter because of the former) and needs to care for all its peoples, not just the fortune, so-called meritocratic neoliberal greed-ridden ruling elites. Maintaining the existence of the IMF, World Bank and kindred institutions isn’t putting people before property, however. And the plutocratic ruling elites are not going to go quietly into any night.