Alexander Mercouris takes us through the blow-by-blow of the first four months of the crisis in Britain, and it’s not a pretty picture.

By Alexander Mercouris

in London

Special to Consortium News

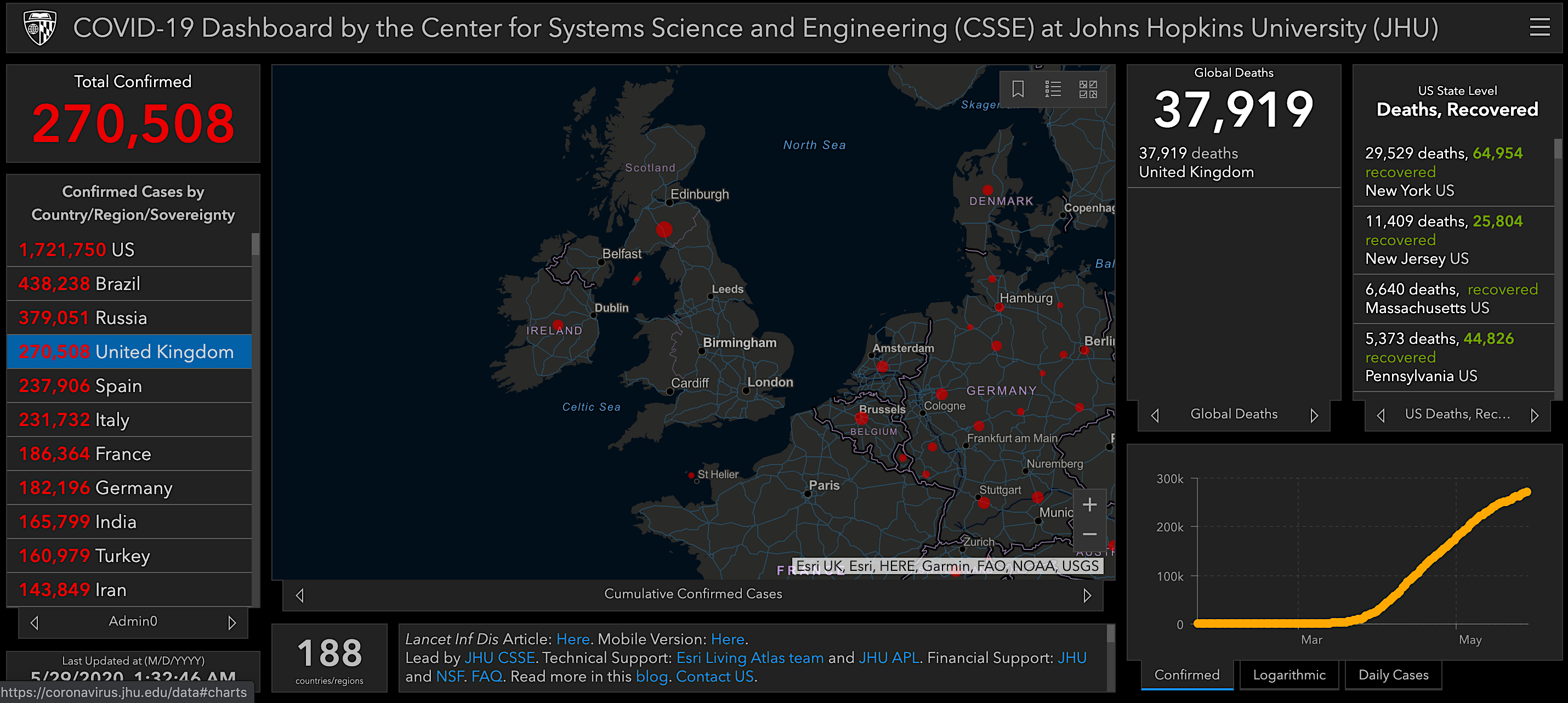

The United Kingdom has had over 270,000 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection as of Friday morning, of whom the great majority have been ill with Covid-19. Of these 37,919 are dead.

The United Kingdom has had over 270,000 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection as of Friday morning, of whom the great majority have been ill with Covid-19. Of these 37,919 are dead.

These are the official figures. It is universally acknowledged, including by the British government, that the true number of SARS-CoV-2 infections, of people ill with Covid-19, and of deaths caused by Covid-19, is much greater than the official figures show.

The Financial Times estimates the true number of deaths caused by the pandemic up to May 1 was more than 50,000. More recent estimates put the total number of deaths in Britain during the Covid-19 epidemic higher still. An article in the FT puts the number of ‘excess deaths’ (that is deaths more than would normally be expected over the same period in an average year) at close to 60,000 in the period since March 20.

However even the official British figure of 37,919 deaths, gross underestimate though it most probably is, is still higher than the official numbers of deaths as of Friday morning reported by Italy (33,142) and Spain (27,119). The official Italian and Spanish numbers of deaths are almost certainly also gross underestimates.

Comparisons with Italy and Spain, bad as they already are, may actually understate the extent of British failure.

Behind the Curve

Britain reported 3,403 new cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection on May 13. On May 26 Britain reported 4,043 new cases, and the next day, 2,013 new cases. By contrast, the number of new cases reported in Italy on May 13 was 888 and on Wednesday it was 584. Spain reported 1,551 on May 13 and 859 on Wednesday.

Comparisons of numbers of cases between countries are problematic to say the least since they may reflect more the intensity and extent of testing than the actual number or growth in the number of infections.

However it is widely accepted, even by the British government, that Italy and Spain are further ahead in the curve of infections than Britain. If so, then that suggests that whilst Italy and Spain may be past the worst, Britain still has some way to go.

In that case the gap between the number of deaths in Britain and the number of deaths in Italy and Spain will grow further.

Overall, Britain now has the highest number of reported deaths during the pandemic of any country in Europe, and the second highest in the world after the United States (100,047? as Friday morning). Note that the United States has a population (331 million) more than four times greater than Britain’s (68 million), whilst the U.S. reported death toll is less than three times greater than Britain’s.

At its simplest, the debacle in Britain is the product of a catalogue of extraordinary mistakes and failures by Britain’s recently re-elected Conservative government and its leader Boris Johnson. A short account of events in Britain since the start of pandemic in January shows that this is so.

Celebrating Brexit in January; Inaction in February

Despite denials, it is now clear that Johnson, the British prime minister who not only leads the Conservative government but who politically completely dominates it and its senior ministers, did not initially take the danger from Covid-19 seriously.

Though by Jan. 21 it was known in London that Chinese authorities had confirmed human to human transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and though authoritative articles about the potential danger from Covid-19 were appearing in the British medical press by the second half of January, the government’s principal focus during this period remained preparing for the celebration of Brexit Day on Jan. 31.

As The Sunday Times revealed in a shocking article on April 19, Johnson skipped the first meeting of Cobra – the British cabinet’s national crisis subcommittee – convened on Jan. 24 to discuss the Covid-19 situation. In the lead up to Brexit Day he chose to attend the Chinese Lunar New Year Celebrations instead.

Brexit Day followed shortly after, with fireworks, a rousing speech from Johnson – in which he promised the “beginning of a new era for an energetic Britain” – and an argument about whether Big Ben (the bell of the clock in the main tower of the British Parliament building) should strike the hour at the moment when Britain did finally leave the European Union.

February: Ousting a Chancellor and going on Holiday

With Brexit “done”, Johnson’s first order of business was not the looming Covid-19 crisis but resolving a bitter power struggle between his finance minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Sayid Javid, and his all powerful special adviser and chief of staff, Dominic Cummings. Johnson predictably sided with Cummings, and on Feb. 13 Javid resigned.

The remaining weeks of February are best characterised as drift, with no purposeful action being taken by the government on any issue.

Throughout February the government’s scientific advisers were raising ever more urgent alarms about Covid-19. However Johnson and the government paid little attention.

Though four more Cobra meetings to discuss the Covid-19 situation did take place during February, Johnson skipped every one, choosing instead to spend the last two weeks of the month away from London with his family in the British Prime Minister’s country retreat in Chevening.

In Johnson’s absence no decisions of any importance to prepare Britain for the onset of the pandemic were taken.

Early March: A ‘Moderate Illness’ and ‘Business as Usual’

After Johnson returned to London from Chevening, with news of the rapidly deteriorating situation in Italy causing growing alarm, and with criticism from the opposition Labour Party that Johnson was a “part time prime minister”, the pace of government activity briefly picked up.

Johnson chaired a Cobra meeting on March 2, the first time he had done so since the start of the pandemic. An action plan involving stepped up testing was supposedly agreed.

Johnson then gave a press conference on March 3 with the government’s top scientific adviser (Sir Patrick Vallance) and its chief medical officer (Chris Whitty) standing alongside him.

Johnson’s tone during this press conference was determinedly upbeat. With hindsight it was extraordinarily complacent.

Johnson spoke of Covid-19 as a “moderate illness” for the great majority of people, and said, “I wish to stress that, at the moment, it’s very important that people consider that they should, as far as possible, go about business as usual.” He advised the British people to wash their hands, as Johnson appeared to do of the crisis.

It turned out that the ‘action plan’ supposedly agreed at the March 2 Cobra meeting was in reality no such thing. Instead it was an outline of a series of contingency measures, which the government said it might take depending on how the situation developed.

Early to Mid-March: Principal Focus: The Budget and the Economy

In reality Johnson’s and the government’s main concern at this time was not the Covid-19 pandemic but the government’s first post-election budget, unveiled by the newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak on March 11.

That budget did acknowledge the Covid-19 pandemic, and did allocate funds to mitigate its effect. However its primary purpose was to provide funds to meet the massive spending commitments Johnson had made to the British electorate during the December general election.

Sunak’s budget received glowing praise from the British media. However it became almost immediately out of date.

On March 6 a crisis meeting of OPEC (the oil producers’ cartel) together with Russia broke up in acrimony when Russia refused a Saudi demand for an oil production cut.

On March 8 Saudi Arabia reacted by launching an oil price war.

Shortly after, and in response to the oil price war, which plunged prices into negative territory for the first time, financial markets around the world entered a tailspin. Only massive intervention by Western governments and central banks – including the British government and the Bank of England – was able to bring it under control.

On March 18, just one week from his budget, Sunak was obliged to announce a further £330 billion spending plan to support the British economy, which dwarfed the £30 billion of extra spending he had announced just a week before in his budget.

The dizzying pace of these events, with Sunak obliged to transform his spending plans over the course of a single week, mirrored the frenetic pace of events in March.

The key fact, however, remains: in the week between the announcement of Sunak’s budget on March 11 and the announcement of Sunak’s rescue package on March 18, it was the crisis in the economy and the implosion of the financial markets, not the Covid-19 pandemic, which were the main area of Johnson’s and the British government’s interest.

Early to Mid March: Shake Hands

On the subject of the Covid-19 pandemic one member of the British government appeared, at least in public, to be largely unconcerned. That person was Boris Johnson.

During his press conference on March 3 Johnson openly bragged that he was defying scientific advice by shaking hands: “I’m shaking hands. I was at a hospital the other night where I think there were a few coronavirus patients and I shook hands with everybody, you’ll be pleased to know.”

On March 5, the day of the first reported British death from Covid-19, Johnson appeared on ITV’s This Morning programme, where he again ignored scientific advice by shaking hands with the TV anchor Philip Schofield.

Despite the fact that the first government minister (Nadine Dorries) fell ill with Covid-19 the next day (March 6) Johnson continued to ignore the advice of his medical officers and scientists over the following days by continuing to shake hands.

On March 7, together with 81,000 other sports fans, he attended an England versus Wales rugby match in Twickenham, where he publicly shook hands with five female rugby players. He even posted on Twitter a video of himself doing it.

Mid-March: Let Sports Fixtures and Rock Concerts Continue

The rugby match at Twickenham was in fact only one of several sports events which, without any interference or objection from the government, continued to take place during this time.

On March 8, French rugby fans travelled to Scotland to watch their team play Scotland.

On March 10, a four day horse-racing festival drawing 60,000 people began in Cheltenham.

On March 11, 3,000 Spanish football fans travelled to Liverpool to watch Liverpool play Atlético Madrid.

In addition, on March 14 and 15, the Welsh rock band the Stereophonics performed at a packed stadium in Cardiff for two nights in a row.

Mid-March: Adopt the Mitigation Strategy and Aim for ‘Herd Immunity’

It is now generally acknowledged, though not formally admitted, that behind the outward facade of insouciance, the Conservative government’s policy during the first two weeks of March was a variant of the mitigation strategy, which is currently still being practised by Sweden.

This amounts to letting the SARS-CoV-2 spread gradually through the population in the hope that this will eventually lead to “herd immunity”, which will bring the epidemic to an end.

Though the mitigation strategy seems to have been the strategy the British government was implicitly following in the first weeks of March, the policy only seems to have fully crystallised at a Cobra meeting chaired by Johnson on March 9.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ 25th Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

Following that meeting the government’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, basically confirmed that the government was following a mitigation strategy when he said publicly that the “next step” would be “to ask” anyone with respiratory symptoms or a fever to self-isolate. However he also said that the government would only “ask” people to do this in “about 10 to 14 days”.

The government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, finally admitted that the government’s policy was indeed the mitigation strategy when he said during a broadcast on BBC radio on March 13 that the government’s intention was to “build up some degree of herd immunity” within the population.

Mid March: Stop Testing

One particularly unfortunate consequence of the British government’s drift into a mitigation strategy was that it resulted in Britain’s testing programme being quietly abandoned.

In the absence of effective drug treatments for Covid-19, a well organised testing and tracing system is essential in order to identify and isolate virus carriers in order to provide early treatment.

Britain had in fact been reasonably quick to get a testing programme off the ground, and was carrying out around 1,500 tests a day in the first days of March.

However, as Britain quietly drifted into a mitigation strategy the number of tests stagnated, so that as numbers of SARS-CoV-2 infections grew, the testing system became overwhelmed.

Ignoring advice from the World Health Organisation, on March 12, shortly after the Cobra meeting three days earlier, the British government halted community testing altogether, re-directing its, by now, inadequate testing resources to checking patients for Covid-19 in hospitals.

In the absence of community testing, no tracing system could be set up, and Britain does not have a properly functioning tracing system to this day.

Mid-March: Warn of Danger, But Take No Action

By March 12 the deteriorating situation in Britain was in fact becoming impossible, even for Johnson to ignore.

By March 12 the deteriorating situation in Britain was in fact becoming impossible, even for Johnson to ignore.

Accordingly, standing in front of two British flags, he delivered a televised statement that day in which he admitted for the first time the gravity of the situation: “This is the worst public health crisis for a generation . . . I must level with you, level with the British public — more families, many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time.”

The contrast was stark with Johnson’s advice given in his March 3 press conference—that for the vast majority of people Covid-19 would be no more than a “moderate” illness and that they should “as far as possible, go about business as usual”.

His dramatic words nine days later came with the belated introduction of the first concrete measure to limit the spread of the infection.

Whereas on March 9 Chris Whitty, the government’s chief medical officer, had said that in about 10 to 14 days time the government might “ask” anyone with respiratory symptoms or a fever to self-isolate, on March 12—just three days later—the government asked people with respiratory symptoms to do precisely that.

The government however failed to ban mass gatherings, or order the isolation of households where one person had symptoms, though it did say that it would do so “at the right time”.

Unsurprisingly, this strange combination of dramatic language and inadequate non-measures – produced derision.

Mid-March: Agree to Lockdown, But Don’t Announce It

By this point events were finally catching up with Johnson.

Over the course of an informal meeting with his senior advisers in Downing Street on Saturday, March 14—just two days after his address to the nation—Johnson finally accepted the need for a full, legally-enforced lockdown.

There has been much debate about why he did so.

Mostly it is said that Johnson and the government were persuaded to change course by two scientific studies, one from Imperial College and one from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Each of these studies predicted tens or even hundreds of thousands of deaths if the government stuck with its mitigation strategy instead of moving towards a legally-enforced, suppression strategy, which included a lockdown.

In my opinion, the story that Johnson changed course because of these two studies is a myth propagated by Johnson’s spin-doctors as they searched for ways to explain away his sudden shift in strategy by attributing it to some sudden change in the “scientific advice”.

In fact the two studies simply re-stated the advice the scientific community had been consistently giving Johnson and the government ever since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in January.

In my opinion what caused the policy to change was not the two scientific studies. It was the dramatic deterioration of conditions in the country, and the darkening of the public mood.

Not only was the government receiving increasingly alarming information about an explosion in the number of Covid-19 cases, but the British public was starting to make decisions by itself without waiting for the government to take action.

Business people were closing their workplaces, laying off workers or telling them to work from home. Panic buying, especially for food, was taking hold in the shops.

Facing the prospect of a massive surge of Covid-19 cases, alarmed by the growing signs of panic and the signs of collapse in the economy, confronted with growing demands for financial support from the business community (which at this time was lobbying intensively for a lockdown, which would release financial aid) and reeling from the hostile reaction to Johnson’s March 12 broadcast, Johnson and the government had little choice but to back down and agree to a lockdown.

Even at this late stage, however, Johnson prevaricated.

In a televised address to the nation on Monday, March 16 the prime minister still balked, despite the decision he had supposedly made two days earlier to impose a lockdown, from actually imposing a lockdown.

Instead he announced further advisory measures, advising Britons to work from home where possible, to avoid restaurants and bars, and to self-isolate at home if someone in their home fell ill.

Late-March: Announce a Lockdown and Blame the People

Not until Monday, March 23, nine days after the decision to impose a legally enforced lockdown was supposedly made, and only amidst rumours of a cabinet revolt, did Johnson in a further broadcast finally announce a lockdown.

Not until Monday, March 23, nine days after the decision to impose a legally enforced lockdown was supposedly made, and only amidst rumours of a cabinet revolt, did Johnson in a further broadcast finally announce a lockdown.

Disingenuously, Johnson’s spin-doctors blamed it on the public, saying it had become necessary because of the failure of a part of the public to heed Johnson’s advice by congregating in parks.

Late March: Release 15,000 Untested Hospital

Patients into Care Homes & the Community

One important decision was, however, made over the course of the week between the March 14 decision to impose a lockdown and the eventual announcement of the lockdown on March 23.

That was a decision, announced by the Health Department on March 19, that 15,000 people would be discharged from hospitals into the community and care homes in order to free up hospital beds for Covid-19 patients.

This was done without any mandatory requirement that they be tested to see if they were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

It is widely believed that this action resulted in the further spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the community and in particular in care homes. Indeed some people, especially amongst those who oppose the lockdown, blame this action as the major cause for Britain’s high Covid-19 death rate.

In the absence of widespread testing it is impossible to say to what extent this is actually true. However what this remarkably ill-judged decision does show is the extent of the chaos and panic at the heart of government during this crucial week.

Late March: The Prime Minister Falls Ill with Covid-19

By this point it was not just events in the country that were catching up with Johnson. It was Covid-19 itself.

On March 27—just three days after he announced the lockdown—Johnson tested positive for Covid-19 and was forced to self-isolate. By April 5 he was seriously ill and had to be taken to hospital. On April 6 he was moved into intensive care.

It is now admitted that for a time Johnson’s life hung in the balance, but he survived and was discharged from hospital on April 9. After a fortnight’s rest at the British prime minister’s official country residence at Chequers he finally returned to work on April 26.

Johnson was not the only member of Britain’s governing elite to fall ill with Covid-19. The first to do so was the junior health minister Nadine Dorries on March 10.

On March 27—the same day Johnson tested positive for Covid-19—Matt Hancock, the health secretary, who is a senior member of the cabinet, did so also, as did the United Kingdom’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty.

On March 28 Cummings, Johnson’s special adviser and chief of staff, who the previous day had driven his wife and son on an extraordinary 264 mile dash from London to the north of England in circumstances which are currently the subject of a major political crisis, also apparently fell ill with Covid-19, though the government did not disclose the fact until March 30. [At a press conference last Monday Cummings said he had never been tested for the disease.]

Earlier, on March 25, Charles, the prince of Wales and heir to the throne, had also tested positive for Covid-19.

The sudden removal from the scene of so many important people, one so soon after the other, shook public confidence. It also created a leadership vacuum at the heart of government, which led to further confusion and chaos.

Late March: Create a Leadership Vacuum and Set the Scene for a Succession Crisis

Johnson made the situation worse by failing to appoint a deputy properly empowered to make decisions in his absence and who might become his successor if he was not able to return.

This decision probably reflected Johnson’s unease about the underlying strength of his political position. He had only recently consolidated his position as prime minister after a bitter factional battle within the Conservative Party, and an election victory brought about more by his Labour opponents’ mistakes than by his own merits.

Inevitably he had made many enemies along the way, with one of the most dangerous being the cabinet office minister, Michael Gove, who makes little secret of his belief that he would make a better prime minister than Johnson. Gove’s position at the heart of government moreover puts him in a strong position to make a bid for power should Johnson disappear from the scene.

Gove, judged purely on ability and position, was in fact the obvious person to be appointed to deputise for Johnson whilst Johnson was ill. However Gove’s position as a potential rival to Johnson automatically ruled him out.

In place of Gove, Johnson designated Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab as the senior minister chairing the cabinet and its subcommittees whilst he was absent.

Raab, who few rate highly or take seriously as a possible future prime minister, was, however, granted only very limited powers by Johnson. He was not authorised to appoint or dismiss officials or ministers, or to make changes to existing policy. His role was in effect that of a glorified government spokesman and temporary chair of the cabinet and its subcommittees.

The British system has no conception of either a deputy prime minister or of an acting prime minister. A number of politicians in previous governments have been called ‘Deputy Prime Minister’ but the title has always been essentially honorific, and has been in the Prime Minister’s gift.

As for an ‘acting prime minister’, the only person in Britain who, according to British constitutional theory, can “act” as prime minister is the prime minister himself.

That meant that the only way someone would have been able to run the government like a prime minister in Johnson’s absence would have been if Johnson had appointed them to that task. Johnson’s failure to do so deprived the government of effective leadership during the harshest period of the lockdown.

Johnson’s decision did not just leave the government leaderless at a crucial time. It also created conditions for a major political crisis had he failed to recover.

Short of a general election or a party leadership election – neither possible during a lockdown – there is no clear constitutional mechanism in Britain to replace a prime minister who dies or becomes indisposed without designating a successor.

In the absence of a clearly designated successor, who the Queen, with the consent of the cabinet, could appoint prime minister to hold office until a general election or a party leadership election were held, the scene would have been set, in the event of Johnson’s failure to return, for a ferocious political battle with no clear rules to determine its outcome.

Fortunately Johnson’s recovery spared Britain that calamity.

April Drift: Fail with Testing and Protective Clothing

In Johnson’s absence the government drifted, in much the same way that it had done whilst he had been away in Chevening in February.

Efforts to restart the community testing programme, abandoned on March 12 at the time when the government was still following the mitigation strategy, ran into bureaucratic and logistical obstacles, which in the absence of someone exercising the functions of the prime minister at the heart of the government, proved difficult to overcome.

An ambitious target of 100,000 tests a day by April 30 was announced, but was only achieved by cutting corners, with the number of tests rapidly falling back to much lower numbers afterwards.

The number of daily tests has fluctuated widely since, with apparently some degree of double counting and administrative confusion.

As of Friday morning, the total tally stands at 3,458,905??, which is in line with the total number of tests done in Germany, Italy and Spain, and is more than double that in France.

However unlike in Germany, the British testing programme only really got underway after the epidemic had already begun to abate. Moreover, it has never been accompanied by a contact tracing system to identify and isolate carriers. As of the time of writing attempts to set up such a contact tracing system are still running into problems. Inevitably that has reduced the overall value and effectiveness of Britain’s testing effort.

The failure to get Britain’s community testing programme underway in an efficient and timely way has been matched by an equal failure to provide Britain’s hospital staff and key workers with proper protective clothing and equipment.

Much of the media reporting in Britain in April centred on this issue, with lurid stories of the failure of the health system’s procurement system and of critical shortages of essential equipment.

These culminated in a fiery BBC TV Panorama documentary broadcast on April 28, which catalogued the failures in unsparing detail, but whose emotional reporting and reliance on the testimony of NHS doctors who turned out to be Labour supporters in turn attracted controversy.

March to May: Leave the Airports Open

The government’s inability to get a grip on the situation was also demonstrated by its failure to impose restrictions on airline flights into the United Kingdom.

The government’s inability to get a grip on the situation was also demonstrated by its failure to impose restrictions on airline flights into the United Kingdom.

Flights continued to arrive from all over the world throughout April, and continue to do so as of the time of writing, including from known Covid-19 hotspots such as Italy, China and New York.

Cursory checks at airports were gradually abandoned over the course of March, with no requirements that airline passengers arriving in Britain should self-isolate or go into quarantine.

As it happens, the worldwide collapse in air travel means that the actual number of air passengers arriving in Britain in April probably slowed to a trickle. A good guess is that a sizeable proportion of those who did come were British citizens, who were obviously entitled to return home anyway.

However the government’s failure to place limits on air passengers’ arrival or to require them to self-isolate or go into quarantine, made a poor impression on a British public living through a lockdown.

There has never been a convincing explanation for this failure, and amidst much acrimony there continues to be debate about it to this day.

Face Masks: Nothing to Say

The government also failed to provide clear guidance on the issue of wearing face masks, despite strong circumstantial evidence from Asian countries that face masks are effective in slowing the spread of the virus and of other infectious diseases.

As a result the wearing of face masks in Britain, where there appears to be a cultural bias against facial covering, has never been widespread.

My guess, based purely on personal observations, is that in my part of London no more than 15-20 percent of people were wearing them at the height of the epidemic, and far fewer are doing so now.

March: A Surge in Infection Rates

Ultimately however, the explanation for Britain’s inordinately high number of deaths during the pandemic must lie with the government’s failure to act decisively during the early stages of the pandemic in February and March, and in its inordinate delay in imposing a lockdown, which did not happen until March 23.

In the absence of proper community testing, any estimate of the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Britain during March can be no more than a guess.

However one study – by Imperial College – estimates that there may have been no more than 11,000 SARS-CoV-2 infections in Britain at the time of Johnson’s press conference on March 3.

On the assumption that the number of infections was doubling every three days, this study estimates that the total number of infections increased to 200,000 by March 14 (the day when Johnson took the decision to impose the lockdown) and increased further to 1.5 million infections by March 23 (the day when he finally imposed the lockdown).

Other studies put both the total number of infections and their rate of increase during this period much lower, with a different study estimating just 3,000 infections on March 3, 43,000 infections on March 14, and 286,000 infections on March 23.

Whatever the precise number of infections, there is little doubt of an explosion of their numbers in March, and it is this, rather than the release of 15,000 hospital patients into the community and into care homes on March 19 that almost certainly accounts for Britain’s very high death toll.

The fact that April 2020 recorded Britain’s highest monthly death toll on record seems to confirm this fact.

April: Order a Lockdown; Don’t Enforce it

The lockdown was erratically enforced across Britain, with it being more lightly enforced and observed in London by comparison to other places in the United Kingdom, where it was enforced and observed far more rigorously, despite London being very much the epicentre of the epidemic in Britain.

The lockdown was erratically enforced across Britain, with it being more lightly enforced and observed in London by comparison to other places in the United Kingdom, where it was enforced and observed far more rigorously, despite London being very much the epicentre of the epidemic in Britain.

The British lockdown was also significantly less rigorous than those imposed in some other countries.

Characteristically, when Johnson announced the lockdown on March 23, legislation had not been passed to enforce it, leaving the police confused about whether they even had the power to do so.

Even after legislation was eventually passed, government guidance on enforcing the lockdown continued to be unclear and inconsistent, causing police forces across Britain to enforce the lockdown in different ways.

One person who has attempted to use ambiguities in the legislation to his advantage, as he has sought to justify his flouting of the government’s advice during the lockdown, is Johnson’s own chief of staff, Cummings.

Nonetheless, the lockdown, after it was eventually imposed, does seem to have significantly slowed the growth in the number of infections, as shown by the steady reduction in the daily numbers of deaths after mid-April.

That appears to confirm that many more lives would have been saved if it had been imposed earlier.

An Incompetent Prime Minister

The individual who had it in his power to impose the lockdown sooner, but who chose not to do so until the situation had almost spiralled out of control, was Boris Johnson.

As Britain’s Prime Minister, and as the undisputed victor of Britain’s long Brexit war, Johnson’s political authority at the start of the year was beyond challenge. The decision whether or not there would be a lockdown therefore depended entirely on him.

Moreover the British political system depends heavily on the prime minister exercising tight control during a crisis. It is the prime minister, and only the prime minister, who is able to give leadership and direction to the cabinet, and who during a crisis must make the various parts of Britain’s complex government structure work together efficiently, and in unison.

It has long been known in British political circles that Johnson, ruthless and clever political tactician though he undoubtedly is, is also lazy, inattentive and easily bored, and that he is a poor manager.

The Covid-19 crisis has exposed the extent to which this is so in the starkest way.

The catalogue of bureaucratic blunders—the failure to create a proper community testing system, the release of 15,000 people without testing from hospitals into the community and care homes, the breakdown of the logistical system leaving front line NHS staff without proper protective clothing or equipment, the failure to impose proper restrictions on air passengers entering the country, and the delay and confusion in the legislation and government guidance which accompanied the lockdown—are all ultimately the result of Johnson’s failure as a manager.

Johnson the Covid-19 Skeptic?

Over and above Johnson’s managerial incompetence, his behaviour throughout the crisis has been marked by an extraordinary level of irresponsibility and recklessness, together with a complete inability to make decisions. That, more even than his incompetence, has been in my estimation, the cause of Britain’s failure during the crisis.

Though the government and the media in Britain prefer not to admit the fact, Johnson’s conduct in February and early March makes it obvious, at least to me, that he was at that time one of those people who discounted the danger of Covid-19. Quite possibly he thought of it as nothing more than a bad flu.

How else to explain his repeated failure to attend Cobra meetings throughout February, and his comments at his press conference on March 3 that Covid-19 was for the great majority of people nothing more than a “moderate illness”, and that they should carry on with “business as usual” so long as they took the precaution to wash their hands?

Moreover Johnson’s habit in the first weeks of March of flouting the advice of his own medical advisers and scientists by repeatedly and publicly shaking hands, can only be explained, at least in my view, as his way of indicating to the public that he did not take the advice about the danger of Covid-19 seriously, and thought that the claims being made about its dangers were alarmist and wrong.

Given Johnson’s openly expressed skepticism about the danger of Covid-19, it is not really surprising that for the first two weeks of March he hid behind the mitigation strategy as an excuse for doing nothing.

Even when the pressure of events began to force itself on him, so that on March 14 he appeared finally to accept the need for a lockdown, he still contrived to delay its introduction for a further nine days.

Even after Johnson tested positive for Covid-19 on March 27 he continued to act for a time as if he was suffering from nothing worse than a bad case of flu. Thus he went on pretending that he was working as usual, posting false statements that he was getting better, when he was actually getting worse.

Consistent with this refusal to take even his own grave illness seriously, Johnson, in the single most irresponsible action of his time as prime minister, refused to designate a properly empowered deputy and potential successor to run things whilst he was ill.

I have already explained how that left the government leaderless during the hardest period of the lockdown, and created the potential for a political crisis had Johnson failed to recover.

In the event, Johnson did eventually recover and returned to work. Descriptions of him, which I have heard, from that time speak of him, unsurprisingly, as a bewildered and exhausted man.

Mid-May: From ‘Stay at Home’ to ‘Stay Alert’

During the following two weeks Johnson, though in theory back in charge, seems to have done little of significance, even as the country continued to live through the lockdown.

During the following two weeks Johnson, though in theory back in charge, seems to have done little of significance, even as the country continued to live through the lockdown.

Gradually however, with the daily number of deaths falling, and with lockdowns being relaxed in continental Europe, pressure on Johnson to relax the lockdown began to grow.

Opinion in the country on whether or not to relax the lockdown was in fact divided. The libertarian wing of the Conservative Party, which had never been happy with the lockdown and which was becoming increasingly worried about its effect on the economy, was however becoming more outspoken.

Johnson, who had in the past relied on the support of the Conservative Party’s libertarian wing to win his factional battles, at first temporised. However, and unsurprisingly, in the end he appeared to do as they asked. In another extraordinary broadcast on Sunday, May 10 he appeared to signal a relaxation of the lockdown, changing the government’s advice from “stay at home” to “stay alert”.

In fact, as many people pointed out, Johnson’s broadcast actually left it unclear whether the lockdown was still in effect or not. The broadcast provoked almost as much derision as Johnson’s earlier disastrous one on March 12.

The response to the broadcast varied considerably depending on the region of the country.

In London, where opposition to the lockdown was strongest, many took Johnson’s remarks as a green light that they could henceforth ignore the lockdown rules entirely.

Elsewhere, for example, in working class communities in the north of England, where the lockdown is strongly supported and is taken very seriously, the lockdown seems to have continued much as before.

This patchy picture continues to this day, though, with the continued decline in the number of daily deaths, the latest word is that Johnson is preparing to ease the lockdown further.

Britain Now Exposed to a Second Wave?

Inevitably this has produced worries that with the SARS-CoV-2 virus still circulating in Britain (on Wednesday 2,013 new cases were reported), and with the government’s long promised contact tracing system still not in proper operation, the premature relaxation of the lockdown has left Britain dangerously exposed to a renewed outbreak of infections and cases.

I earnestly hope that this is not the case.

However, what seems to me to be indisputable is the extent of the failure that there has already been.

The Price of Johnson

Some will no doubt say that in discussing this failure I have focused too much on the failings of one individual – Boris Johnson – and have lost sight of Britain’s deeper structural problems, which are the ultimate cause.

I do not deny those problems. I accept that – as shown by the Blair government’s earlier mishandling of the 2001 foot and mouth crisis – Britain’s political and governmental system no longer works with the same efficiency as it once did.

However in a crisis like the one caused by the Covid-19 epidemic the quality of political leadership matters a great deal, and it appears that on every important count Johnson failed.

Given the tens of thousands of deaths, many of which could have been prevented, it seems to me only proper to point to the responsibility of Johnson, who was the person who was ultimately in charge.

“Resolute to be Irresolute”: What Johnson’s Hero Churchill Might Have Said

This is especially so in the case of a political leader like Johnson, who likes to cut a heroic figure, and who goes out of his way to invite comparisons between himself and his hero Winston Churchill, whose biography he once wrote.

In reality, though having reactionary and imperialist views, which Johnson prefers to skate over, Churchill was, whilst leader of Britain’s wartime government, an effective and hardworking manager with a highly capable deputy (Clement Attlee) always ready if needed to step into his shoes.

Above all, Churchill possessed the power of decision, which is something which Johnson clearly lacks.

Speaking for myself, I cannot help but think that if Johnson’s hero Churchill were around today to assess the quality of Johnson’s leadership and of his government, he would assess them harshly, finding them less like his own, and more like the interwar government, which Churchill once harshly criticised:

“The government simply cannot make up their mind or they cannot get the prime minister to make up his mind. So they go on in strange paradox, decided only to be undecided, resolved to be irresolute, adamant for drift, solid for fluidity, all powerful for impotency. And so we go on preparing more months, more years, precious perhaps vital for the greatness of Britain for the locusts to eat.”

In Johnson, the price of his “resolution to be irresolute” is measured in tens of thousands of British lives.

Alexander Mercouris is a political commentator and editor of The Duran.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ 25th Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

The second paragraph sums it up – “The official figures are “officially” acknowledged to be not true.”

Nobody knows who or what they are counting, or why.

Trump and Johnson are two peas in a pod, they are both entertainers . . . If that is what the English speaking public wants then they will both be reelected . . .

Meanwhile reality interjects . . . Soaring rates of death in the US and riots by the disenfranchised . . .

But in Australia, where a caring leader led the country to 100 (??? Is this really true?) deaths.

Wow, what a contrast!!!

Thank you for a thorough diary and analytical perspective. I for one have never trusted Boris Johnson; as London’s mayor he was an utter buffoon. He may wish to emulate Churchill but as you state he is indecisive and lazy. Standing by Dominic Cummings will ultimately bring about his downfall. He is not listening to the scientists, he is not taking heed of the British public and by trying to silence the press as we recently witnessed this week will backfire on him. He is making a great many people angry by his dithering. Does he not realise the seriousness of the situation! How dare he ride roughshod over the lives of ordinary people and treat them as though they don’t matter.

Boris and Trump are two peas in the same pod.

I am posting a link below that will prove this and you’ll be able to see for yourselves how unfit for high office Boris is.

He got the gig with the help of a right wing complicit British media largely owned by Murdoch & the non domiciled (tax evading) Lord Rothermere; their combined efforts stitched up Jeremy Corbyn in an appalling unprecedented character assassination that spanned almost 4 years (similar to Sanders I guess).

Boris has been sacked a few times, he’s lied constantly throughout his privileged career, his old boss at the Daily Telegraph said:

“ I have argued for a decade that, while he is a brilliant entertainer who made a popular maître d’ for London as its mayor, he is unfit for national office, because it seems he cares for no interest save his own fame and gratification.”

No one knows how many illegitimate children Boris has had, I keep seeing 9 in various comments pages; he did force one woman to have an abortion and this is common knowledge here in the UK.

He also wasted £50m of taxpayers money on a garden bridge across the Thames that did not see a single brick laid, it was purely a vanity project during his disastrous tenure as Mayor.

The sad thing is that the masses will probably vote for him again if given the chance. It’s a messed up situation alright.

So Trump & Boris, same sh*t different shoe..

hXXps://www.mirror.co.uk/news/politics/37-lies-gaffes-scandals-make-18558695

Alex, if it makes you feel any better, the US totals are undoubtedly well under what is real, but our munted governments in many cases refuse to admit it. Our testing has been mainly a joke, and tracing non-existent. In Florida, where I reside, medical examiners were told to shut up regarding any public statements, and the woman who set up Florida’s system of identification of cases and deaths was sacked because she made public her lack of support for the obvious state policy of undercounting said cases and deaths. Then, she was maliciously smeared by the Governor and his party. And then, of course, Trump. I know it seems unlikely, but it actually could be a lot worse.

Thanks to Mr. Mercouris for this clear presentation. The decisions were difficult compromises. but too little was done too late, as in the US, which also has done almost no contact tracing, although that had succeeded marvelously in China, Hawaii and elsewhere.

That is likely worse than incompetence, and more than a bit suspect.

He ain’t no Churchill, that’s for sure.

Perceptive analysis as usual from Alex.

…except in the final paragraphs, which fail to note the one glorious hope that Johnson may yet rely upon, that like Churchill, his history may one day completely obfuscate and obliterate his criminal disregard for moral, ethical, humane, or even civilized concern for human life.