Diana Johnstone’s newly-published memoir offers an incisive, gritty, politically alert, and expansive account of post-war Europe, reports Patrick Lawrence in this interview with the author.

By Patrick Lawrence

Special to Consortium News

Diana Johnstone first sojourned in Paris during the early postwar years, as France and the rest of Europe were coming back to life—and as America set out to build an empire amid the Cold War frenzies of the McCarthy years.

Diana Johnstone first sojourned in Paris during the early postwar years, as France and the rest of Europe were coming back to life—and as America set out to build an empire amid the Cold War frenzies of the McCarthy years.

Nearly seven decades later, Johnstone’s place among the distinguished Europe correspondents of our time lies beyond dispute. A Minnesota native, she is a French citoyen now and remains a Parisienne. “If I must claim a label,” Johnstone, 89, writes in her just-published personal and political memoir, “it would be that of an independent truth-seeker.”

Circle in the Darkness (Clarity Press) —Johnstone takes the title from Einstein—is a moving, incisive, gritty, politically alert, and always humane account of Johnstone’s long decades as a Europeanist. In the interview that follows, we touched on many of the topics she has long covered in her news reports, commentaries, and books: the trans–Atlantic rift, the fate of the European Union, Europe’s search for an independent voice and the Continent’s relations with Russia. She told me: “I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.”

decades as a Europeanist. In the interview that follows, we touched on many of the topics she has long covered in her news reports, commentaries, and books: the trans–Atlantic rift, the fate of the European Union, Europe’s search for an independent voice and the Continent’s relations with Russia. She told me: “I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.”

I conducted this interview via email over the course of several months, during which the spread of the Covid–19 virus confined Johnstone to her Paris apartment. Per usual, she had a take on the political ramifications of this global calamity. “The Covid–19 crisis makes it just that much clearer that the European Union is no more than a complex economic arrangement,” Johnstone said toward the end of our exchange, “with neither the sentiment nor the popular leaders that hold together a nation.”

P.L. You’ve known France and Europe through all sorts of phases—postwar reconstruction, the so-called trente glorieuses [1945–75], the ’68 “events” and their aftermath, the drift away from a native social democracy toward Anglo–American neoliberalism. How would you describe this arc? What has propelled Europe in the direction it has taken—which, maybe you agree, is an unfortunate trajectory? I suppose I’m looking for historical context and causality.

D.J. That’s a very big question, which is hard for me to answer without going on and on. I suppose you could describe this arc in terms of the Americanization of France, which has risen over the decades and may be declining mainly because America’s attractiveness as a model is declining, not only in France.

Shall we look at the history?

French soldiers guarding a Metro entrance in Paris, France at the beginning of World War I.(Bain News Service/Wikimedia Commons)

You have to go back to the First World War to understand the process. The war of 1914 to 1918 bled the youth of the nation—over half the armed men were casualties, with heavy losses among the young officers. France came out of that horrendous bloodbath among the victors, got back Alsace–Lorraine, and was exhausted, more than willing to consider that one “war to end all wars” was enough. Germany was also bled but came out bitterly resentful, with the results we all know: a second war meant to correct the first. What I’m getting at is that the French reluctance to fight another war with Germany cannot be explained—as some do—by latent sympathy for Nazi ideas, although such sympathy existed throughout Europe at the time—more so, surely, in Britain. It’s simply that in France, the feeling of being eager to die for a righteous cause had been used up 20 years earlier.

France’s rapid surrender to the German blitz in 1940 was a trauma whose scars have never been healed. The role of “the Resistance,” with a capital “R,” was mainly to salvage what could be salvaged of national pride. It also prepared for the social democracy of the postwar period, with the program of the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR, National Resistance Council), accepted across the political spectrum as necessary for national unity. It called for universal social security, nationalization of banks and key industries, women’s suffrage—finally!—and other social measures.

Interesting. These connections are not much appreciated in the U.S. How does your own experience fit with this history, “an American in Paris”?

I first made acquaintance with Paris in the mid–1950s. It was not in ruins like Germany or damp and dreary as London, but my impression was that morale was not high. You could feel an underlying resistance to America’s whopping shadow, in some ways a continuation of the passive resistance to Nazi occupation, as most resistance is always passive. The more tangible resistance came from more or less the same players as the Resistance against Nazi occupation: the French Communist Party and conservative patriots.

In Eastern Europe, the new Russian occupation was military and political. In France, the American occupation was only slightly military but primarily cultural. Its beginnings showed the happy face of American jazz. You could even be a bit anti–American and love jazz thanks to the black musicians.

And jazz by no means drove out the internationally popular French singers who provided part of the background music of the era: Georges Brassens, Edith Piaf, Juliette Greco, Charles Trenet, Yves Montand, many more. Although vaguely demoralized, Paris still aspired to the role of vanguard of intellectual life, thanks to “existentialism”—not only the worldwide prestige of Jean–Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but a lifestyle appropriate to recovering from a bad illness.

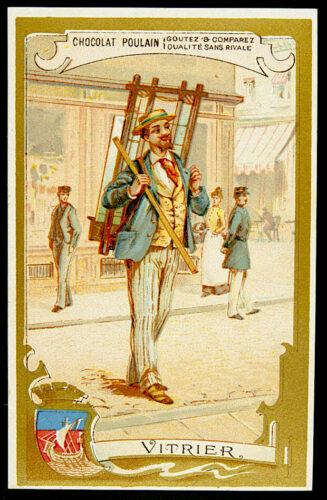

In those days you could open your window to street singers and throw them a little money. And there were the men who walked through the city with sheets of glass on their backs crying “Vitrier! Vitrier!” [Glazier! Glazier!] on the chance that your windowpane was broken and you needed to have it fixed.

In those days you could open your window to street singers and throw them a little money. And there were the men who walked through the city with sheets of glass on their backs crying “Vitrier! Vitrier!” [Glazier! Glazier!] on the chance that your windowpane was broken and you needed to have it fixed.

And there were the movies, black-and-white but never Manichean. Without putting the word on it, that was what first won me over: the absence of the emphatic moral dualism of American movies. Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête, the wistful amoralism of young Gérard Philippe in Le diable au corps—no actor was showing off how good he was, and there was no one to hate.

Meanwhile in the ’50s, France was losing colonial wars in Indochina and North Africa, and its politics were like the game of pick-up-sticks.

In 1958, de Gaulle took over, going on to end both American military occupation and French colonialism, choosing to seek independent relations with the whole world. Culture Minister André Malraux returned the blackened façades of Paris buildings to their original cream color, industry flourished, French “New Wave” cinema excelled.

Thank you. Wonderful context. Let’s keep going into the ’60s.

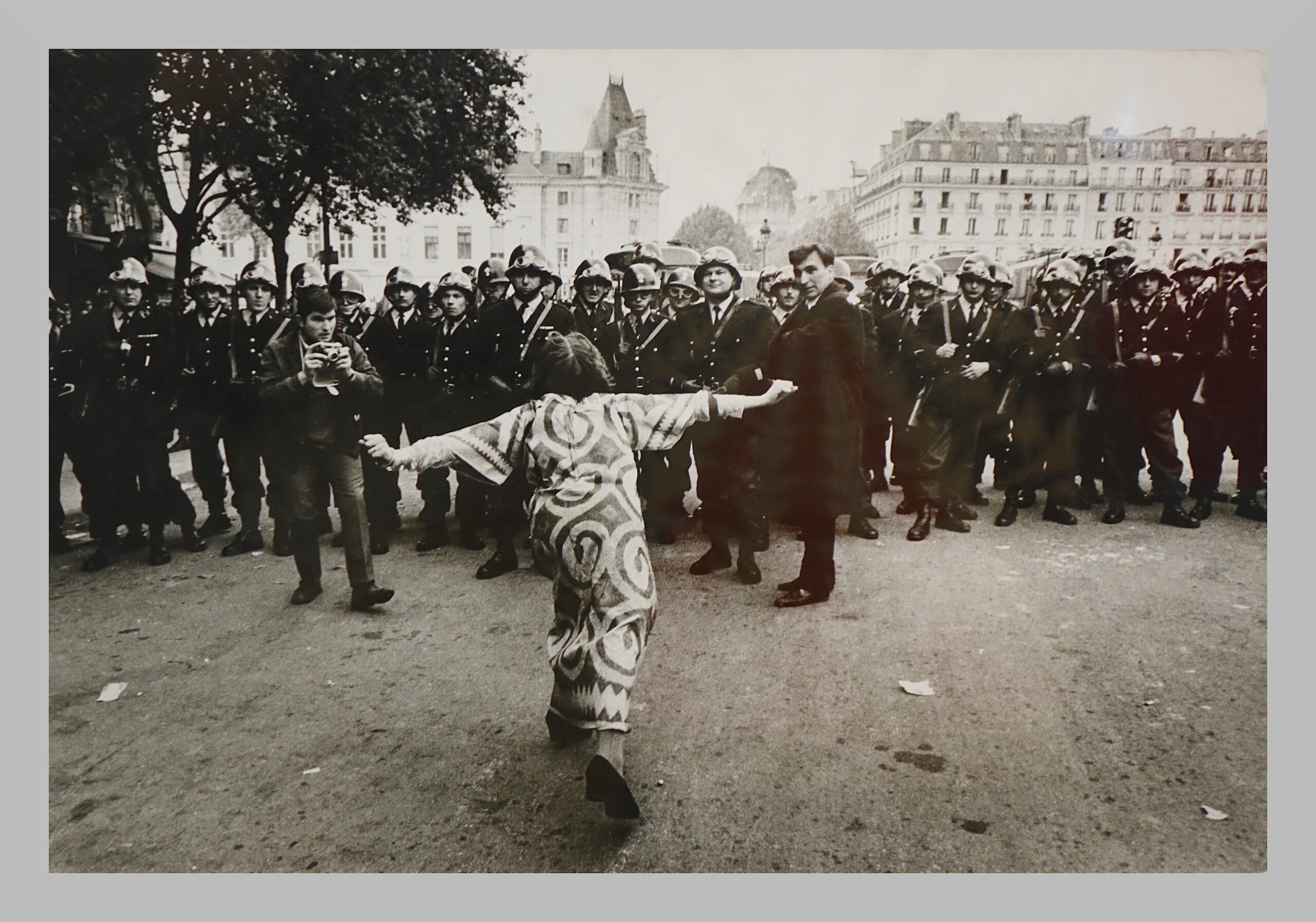

The paradox of the ’60s was that just as de Gaulle was de–Americanizing France on the geopolitical level, the totally baby-boom postwar generation was Americanizing in its own peculiar way. As the country prospered, a squeaky-clean new generation clumsily Americanized with the “YéYé” singers, “surprise parties,” “flirts”, and “standing” (instead of the good French word prestige).

The celebrations of Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six Day War were closely followed by a fresh focus on the crimes of the Occupation, notably the deportation of Jews. This plunged the nation into guilt—a guilt the young generation avoided by dissociating from the nation.

You’re talking about that period when the export of American culture was turned into a Cold War weapon.

America was innocent. The fascination with a mythical America, spread worldwide by the U.S. entertainment industry, often with government sponsorship, still prepares people to despise their own country as backward. This sets the stage for fatalistic acceptance of U.S. pressure to conform to the U.S. concept of American exceptionalism even in world affairs. This was only temporarily set back by the war in Vietnam—the Americans themselves were against the war, weren’t they? I was one of those who helped make it seem that way.

Please Donate to CNs’ 25th

Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

The May ’68 generation, which had grown up as things got steadily better, rejected both the authority of Gaullist paternalism and the discipline of the Communists. The result was a hedonistic individualism, intellectualized by Foucault [Michel Foucault, the late philosopher and theorist] and others as “resistance” to ubiquitous “power.” In this respect, by its “theorists,” French philosophy actually hastened the Americanization of France, and even of America itself. By constantly attacking, deconstructing, and denouncing every remnant of human “power” they could spot, the intellectual rebels left the power of “the markets” unimpeded, and did nothing to stand in the way of the expansion of U.S. military power all around the world.

The “anti-power” generation ended up condemning its own country, France, for its colonial past, while showing scant concern over the overwhelming current power of the United States as it destroys one country after another—sometimes with France taking part, as in Libya. There is also the fact, hard to demonstrate in detail, that through networks like the Young Leaders program of the French–American Foundation, United States officials get a crack at indoctrinating, selecting, or at least vetting up-and-coming French political personalities.

So well explained, Diana. And we come to the neoliberal phase, which has always struck me as odd, given it derived from the Anglo–American tradition, not the Continent’s.

With Emmanuel Macron, France seems to have the anti–de Gaulle, the most American president ever. And that may help trigger a change of course. Donald Trump is also, in his way, the most “American” president in recent times, in ways that do not appeal to people in Europe. The United States looks more and more like a madhouse, and its foreign policy threatens the interests and even survival of Europe, so the time has come for the arc to descend.

At what point and why did Europe surrender its independence within the Atlantic alliance—or did it never, during the early postwar years, achieve any independence to speak of?

The whole point of the Atlantic alliance was to institutionalize Western Europe’s surrender of its independence. And that was decided at Yalta—where Western Europe was not represented, not even by France, to the great chagrin of de Gaulle. There was an attempt at independence in the decade of President de Gaulle. But this bold course did not gain overwhelming domestic support. The only other independent European leader was Olof Palme [Swedish prime minister, 1969–76; 1982 until his assassination in 1986], but Sweden was not part of the Atlantic alliance and Palme’s relative neutrality was always heartily disliked by most of the Swedish upper classes and military leaders.

Can you reflect upon de Gaulle in this context? He is not much understood among Americans—not for his insistence on French independence and certainly not for his economic and industrial policies—his conception of society altogether. Can you say a little about this, and de Gaulle’s idea of French, and by extension European independence? Should we think of his domestic program as of a piece with his thoughts on the international side?

Not much understood? I’d say he has been totally and willfully misunderstood. There are relatively few Americans who can begin to understand a leader determined to maintain his country’s independence from America, and those few have generally had to live abroad to get the point. De Gaulle was a conservative, not a free-market liberal, who saw social reforms benefiting the working class as necessary for national coherence. The mixed economy he favored is not altogether unlike “socialism with Chinese characteristics”—a strong state role to encourage rapid industrial growth, with the rest left to free enterprise. It was a most successful formula. Of course, the political system was quite different.

Having a sense of history, de Gaulle saw that colonialism had been a moment in history that was past. His policy was to foster friendly relations on equal terms with all parts of the world, regardless of ideological differences. I think that Putin’s concept of a multipolar world is similar. It is clearly a concept that horrifies the exceptionalists.

De Gaulle had an organic concept of the nation, a living thing that develops its own identity, and in this view each nation needs to be able to live its own life. This is a conservative, not an aggressive nationalism. The United States is an ideological nation, whose “values” and institutions should be welcomed or imposed everywhere. France has tried that, with Napoleon Bonaparte. The retreat from Moscow [ending Bonaparte’s Russian campaign in 1812] is a lesson to be learned in Washington.

Is there any Gaullist streak in French or European discourse today? He certainly left his mark elsewhere—there is a self-consciously Gaullist strain in Japanese thinking, for instance—often submerged but ever there, the impulse to break free of the suffocating embrace, let’s call it. Any such thing in France or elsewhere in Europe today?

President Kennedy and President De Gaulle at the conclusion of their talks at Elysee Palace, Paris, France, June 2, 1961. (John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston)

Fifty years after his death, just about everyone in France claims to be “Gaullist.” They certainly aren’t, but this indicates that there is deep dissatisfaction with the way things are going. I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.

Do you think “the right moment” is upon us or approaching? There are certainly signs of it—all the dissatisfaction Trump has provoked, the extraordinary “declarations of independence” that followed the disastrous NATO and G–7 summits in 2017. What is your reading of “the moment”?

Amazing. Just as you were asking about the big moment, here comes a big moment that is not what any of us were expecting. This sudden disruption of our lives by a virus is a reminder that the future is always unknown and predictions are vain.

The dissatisfactions that were building up before the pandemic hit are all there, many of them exacerbated by the health crisis—but also overshadowed by the new problems it creates. During months of Yellow Vest protests and strikes against government austerity measures, nurses were in the forefront, braving violent repression to protest against their deteriorating working conditions. The Covid–19 crisis has shown just how right they were! They are now popularly regarded as heroes.

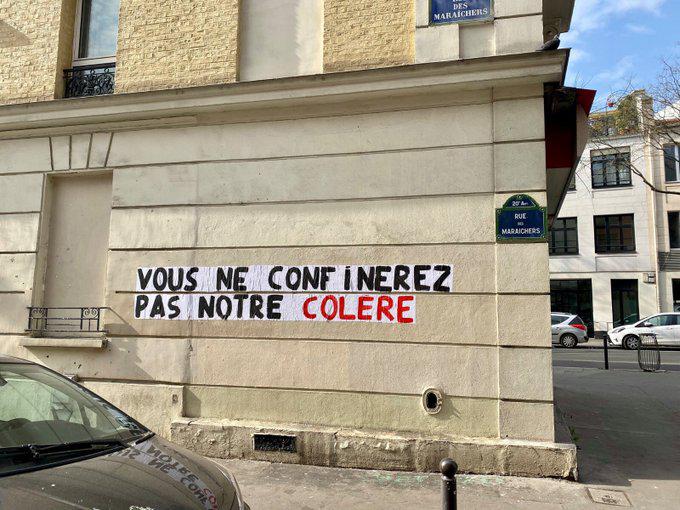

So long as we’re on the subject, what has been the general response to officially ordered confinements during the Covid–19 crisis? Over here we’re seeing mounting protests against them—people demanding that restrictions ease.

In France, confinement has been generally well accepted as necessary, but that does not mean people are content with the government—on the contrary. Every evening at eight, people go to their windows to cheer for health workers and others doing essential tasks, but the applause is not for President Macron.

Macron and his government are criticized for hesitating too long to confine the population, for vacillating about the need for masks and tests, or about when or how much to end the confinement. Their confusion and indecision at least defend them from the wild accusation of having staged the whole thing in order to lock up the population.

What we have witnessed is the failure of what used to be one of the very best public health services in the world. It has been degraded by years of cost-cutting. In recent years, the number of hospital beds per capita has declined steadily. Many hospitals have been shut down and those that remain are drastically understaffed. Public hospital facilities have been reduced to a state of perpetual saturation, so that when a new epidemic comes along, on top of all the other usual illnesses, there is simply not the capacity to deal with it all at once.

The neoliberal globalization myth fostered the delusion that advanced Western societies could prosper from their superior brains, thanks to ideas and computer startups, while the dirty work of actually making things is left to low-wage countries. One result: a drastic shortage of face masks. The government let a factory that produced masks and other surgical equipment be sold off and shut down. Having outsourced its textile industry, France had no immediate way to produce the masks it needed.

Meanwhile, in early April, Vietnam donated hundreds of thousands of antimicrobial face masks to European countries and is producing them by the million. Employing tests and selective isolation, Vietnam has fought off the epidemic with only a few hundred cases and no deaths.

You must have thoughts as to the question of Western unity in response to Covid–19.

In late March, French media reported that a large stock of masks ordered and paid for by the southeastern region of France was virtually hijacked on the tarmac of a Chinese airport by Americans, who tripled the price and had the cargo flown to the United States. There are also reports of Polish and Czech airport authorities intercepting Chinese or Russian shipments of masks intended for hard-hit Italy and keeping them for their own use.

The absence of European solidarity has been shockingly clear. Better-equipped Germany banned exports of masks to Italy. In the depth of its crisis, Italy found that the German and Dutch governments were mainly concerned with making sure Italy pays its debts. Meanwhile, a team of Chinese experts arrived in Rome to help Italy with its Covid–19 crisis, displaying a banner reading “We are waves of the same sea, leaves of the same tree, flowers of the same garden.” The European institutions lack such humanistic poetry. Their founding value is not solidarity but the neoliberal principle of “free unimpeded competition.”

How do you think this reflects on the European Union?

Member states flags outside European Parliament, Strasbourg. (© European Union 2017 – European Parliament)

The Covid–19 crisis makes it just that much clearer that the European Union is no more than a complex economic arrangement, with neither the sentiment nor the popular leaders that hold together a nation. For a generation, schools, media, politicians have instilled the belief that the “nation” is an obsolete entity. But in a crisis, people find that they are in France, or Germany, or Italy, or Belgium—but not in “Europe.” The European Union is structured to care about trade, investment, competition, debt, economic growth. Public health is merely an economic indicator. For decades, the European Commission has put irresistible pressure on nations to reduce the costs of their public health facilities in order to open competition for contracts to the private sector—which is international by nature.

Globalization has hastened the spread of the pandemic, but it has not strengthened internationalist solidarity. Initial gratitude for Chinese aid is being brutally opposed by European Atlanticists. In early May, Mathias Döpfner, CEO of the Springer publishing giant, bluntly called on Germany to ally with the U.S.—against China. Scapegoating China may seem the way to try to hold the declining Western world together, even as Europeans’ long-standing admiration for America turns to dismay.

Meanwhile, relations between EU member states have never been worse. In Italy and to a greater extent in France, the coronavirus crisis has enforced growing disillusion with the European Union and an ill-defined desire to restore national sovereignty.

Corollary question: What are the prospects that Europe will produce leaders capable of seizing that right moment, that assertion of independence? What do you reckon such leaders would be like?

The EU is likely to be a central issue in the near future, but this issue can be exploited in very different ways, depending on which leaders get hold of it. The coronavirus crisis has intensified the centrifugal forces already undermining the European Union. The countries that have suffered most from the epidemic are among the most indebted of the EU member states, starting with Italy. The economic damage from the lockdown obliges them to borrow further. As their debt increases, so do interest rates charged by commercial banks. They turned to the EU for help, for instance by issuing eurobonds that would share the debt at lower interest rates. This has increased tension between debtor countries in the south and creditor countries in the north, which said nein. Countries in the eurozone cannot borrow from the European Central Bank as the U.S. Treasury borrows from the Fed. And their own national central banks take orders from the ECB, which controls the euro.

What does the crisis mean for the euro? I confess I’ve lost faith in this project, given how disadvantaged it leaves the nations on the Continent’s southern rim.

The great irony is that “a common currency” was conceived by its sponsors as the key to European unity. On the contrary, the euro has a polarizing effect—with Greece at the bottom and Germany at the top. And Italy sinking. But Italy is much bigger than Greece and won’t go quietly.

The German constitutional court in Karlsruhe recently issued a long judgment making it clear who is boss. It recalled and insisted that Germany agreed to the euro only on the grounds that the main mission of the European Central Bank was to fight inflation, and that it could not directly finance member states. If these rules were not followed, the Bundesbank, the German central bank, would be obliged to pull out of the ECB. And since the Bundesbank is the ECB’s main creditor, that is that. There can be no generous financial help to troubled governments within the eurozone. Period.

Is there a possibility of disintegration here?

The idea of leaving the EU is most developed in France. The Union Populaire Républicaine, founded in 2007 by former senior functionary François Asselineau, calls for France to leave the euro, the European Union, and NATO.

The party has been a didactic success, spreading its ideas and attracting around 20,000 active militants without scoring any electoral success. A main argument for leaving the EU is to escape from the constraints of EU competition rules in order to protect its vital industry, agriculture, and above all its public services.

A major paradox is that the left and the Yellow Vests call for economic and social policies that are impossible under EU rules, and yet many on the left shy away from even thinking of leaving the EU. For over a generation, the French left has made an imaginary “social Europe” the center of its utopian ambitions.

“Europe” as an idea or an ideal, you mean.

Decades of indoctrination in the ideology of “Europe” has instilled the belief that the nation-state is a bad thing of the past. The result is that people raised in the European Union faith tend to regard any suggestion of return to national sovereignty as a fatal step toward fascism. This fear of contagion from “the right” is an obstacle to clear analysis which weakens the left… and favors the right, which dares be patriotic.

Two and a half months of coronavirus crisis have brought to light a factor that makes any predictions about future leaders even more problematic. That factor is a widespread distrust and rejection of all established authority. This makes rational political programs extremely difficult, because rejection of one authority implies acceptance of another. For instance, the way to liberate public services and pharmaceuticals from the distortions of the profit motive is nationalization. If you distrust the power of one as much as the other, there is nowhere to go.

Such radical distrust can be explained by two main factors—the inevitable feeling of helplessness in our technologically advanced world, combined with the deliberate and even transparent lies on the part of mainstream politicians and media. But it sets the stage for the emergence of manipulated saviors or opportunistic charlatans every bit as deceptive as the leaders we already have, or even more so. I hope these irrational tendencies are less pronounced in France than in some other countries.

I’m eager to talk about Russia. There are signs that relations with Russia are another source of European dissatisfaction as “junior partners” within the U.S.–led Atlantic alliance. Macron is outspoken on this point, “junior partners” being his phrase. The Germans—business people, some senior officials in government—are quite plainly restive.

Russia is a living part of European history and culture. Its exclusion is totally unnatural and artificial. Brzezinski [the late Zbigniew Brzezinski, the Carter administration’s national security adviser] spelled it out in The Great Chessboard: The U.S. maintains world hegemony by keeping the Eurasian landmass divided. But this policy can be seen to be inherited from the British. It was Churchill who proclaimed—in fact welcomed—the Iron Curtain that kept continental Europe divided. In retrospect, the Cold War was basically part of the divide-and-rule strategy, since it persists with greater intensity than ever after its ostensible cause—the Communist threat—is long gone.

I hadn’t put our current circumstance in this context.

The whole Ukrainian operation of 2014 [the U.S.–cultivated coup in Kyiv, February 2014] was lavishly financed and stimulated by the United States in order to create a new conflict with Russia. Joe Biden has been the Deep State’s main front man in turning Ukraine into an American satellite, used as a battering ram to weaken Russia and destroy its natural trade and cultural relations with Western Europe.

U.S. sanctions are particularly contrary to German business interests, and NATO’s aggressive gestures put Germany on the front lines of an eventual war.

But Germany has been an occupied country—militarily and politically—for 75 years, and I suspect that many German political leaders (usually vetted by Washington) have learned to fit their projects into U.S. policies. I think that under the cover of Atlantic loyalty, there are some frustrated imperialists lurking in the German establishment, who think they can use Washington’s Russophobia as an instrument to make a comeback as a world military power.

But I also think that the political debate in Germany is overwhelmingly hypocritical, with concrete aims veiled by fake issues such as human rights and, of course, devotion to Israel.

We should remember that the U.S. does not merely use its allies—its allies, or rather their leaders, figure they are using the U.S. for some purposes of their own.

What about what the French have been saying since the G–7 session in Biarritz two years ago, that Europe should forge its own relations with Russia according to Europe’s interests, not America’s?

I think France is likelier than Germany to break with the U.S.–imposed Russophobia simply because, thanks to de Gaulle, France is not quite as thoroughly under U.S. occupation. Moreover, friendship with Russia is a traditional French balance against German domination—which is currently being felt and resented.

Stepping back for a broader look, do you think Europe’s position on the western flank of the Eurasian landmass will inevitably shape its position with regard not only to Russia but also China? To put this another way, is Europe destined to become an independent pole of power in the course of this century, standing between West and East?

At present, what we have standing between West and East is not Europe but Russia, and what matters is which way Russia leans. Including Russia, Europe might become an independent pole of power. The U.S. is currently doing everything to prevent this. But there is a school of strategic thought in Washington which considers this a mistake, because it pushes Russia into the arms of China. This school is in the ascendant with the campaign to denounce China as responsible for the pandemic. As mentioned, the Atlanticists in Europe are leaping into the anti–China propaganda battle. But they are not displaying any particular affection for Russia, which shows no sign of sacrificing its partnership with China for the unreliable Europeans.

If Russia were allowed to become a friendly bridge between China and Europe, the U.S. would be obliged to abandon its pretensions of world hegemony. But we are far from that peaceful prospect.

Patrick Lawrence, a correspondent abroad for many years, chiefly for the International Herald Tribune, is a columnist, essayist, author and lecturer. His most recent book is “Time No Longer: Americans After the American Century” (Yale). Follow him on Twitter @thefloutist. His web site is Patrick Lawrence. Support his work via his Patreon site.

Please Donate to CNs’ 25th

Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

In response to OyaPola, one of the most dramatic moments in my year in Aix was my encounter with a harki (an Algerian who fought with the French army against the National Liberation Front). I was leaving my apartment as night was approaching and this very agitated young man asked if I could take him in for the night as he had seen people who were actively seeking to assassinate him as soon as it was dark. With his terrified look I did not doubt his word, and I had a spare bed, so I made it available. What he told me was that Moslems who killed other Moslems would have to forfeit their own lives, according to their religious teaching. So you had revenge-seeking Moslems methodically tracking down harkis in departmental France with a view to assassination. But I think we’re straying from Diana Johnstone’s excellent observations.

“This sudden disruption of our lives by a virus is a reminder that the future is always unknown and predictions are vain.”

Hence the opponents seek to restrict the agency of others to prediction/spectatorship since “the future” is predicated on inter-action.

Really interesting. Will seek out more work by this author.

Wonderful interview, rich, nuanced, so enticing I look forward to reading the memoir when it arrives. My thanks to Johnstone, Lawrence and CN for publishing this gem.

I once read a comment elsewhere saying that, back in 1989, both Britain (under Margaret Thatcher) and the US objected to German reunification. Since they could not stop the reunification, they insisted that Germany accept the incoming euro. A heap of German university professors jumped up and protested, knowing fully well what the game was: namely the creation of a banker’s empire in Europe controlled by private bankers.

France and Britain rejected the german reunification. The americans were supportive, even though they had their demands. Mainly privatisation of german public utilities. After agreeing to those demands the americans persuaded the british and pressured the french who agreed to german reunification after germany agreed to the euro.

So why did france want the euro?

The german central bank crashed the european economy after reunification with high interest rates. This was because of above average growth rates mainly in eastern germany. Main function of the Bundesbank is to keep inflation low, which is more important to them than anything else. Since germanys D Mark was the leading currency in europe the rest of europe had to heighten their interest rates too, witch lead to great economic problems within europe. Including France.

“namely the creation of a banker’s empire in Europe controlled by private bankers.”

Resort to binaries (controlled/not controlled) is a practice of self-imposed blindness.

In any interactive system no absolutes exist only analogues of varying assays since “control” is limited and variable.

In respect of what became the German Empire this relationship predated and facilitated the German Empire through financing the war with Denmark in 1864 courtesy of the arrangements between Mr. von Bismark and Mr. Bleichroder.

The assay of “control of bankers” has varied/increased subsequently but never attained the absolute.

It is true that finance capital perceived and continues to perceive the European Union as an opportunity to increase their assay of “control” – the Austrian banks in conjunction with German bank assigning a level of priority to ressurecting spheres of influence existing prior to 1918 and until 1945.

One of the joint projects at a level of planning in the early 1990’s was delevopment of the Danube and its hinterland from Regensburg to Cerna Voda/Constanta in Romania but this was delayed in the hope of curtailment by some when NATO bombed Serbia in 1999 (Serbia not being the only target – so much for honesty-amongst-theivesness.)

This project was resurrected in a limited form primarily downstream from Vidin/Calafat from 2015 onwards given that some states of the former Yugoslavia were not members of the European Union and some were within spheres of influence of “The United States of America”.

As to France, “Vichy” and Europa also facilitated the ressurection of finance capital and increase in its assay of control after the 1930’s, some of the practices of the 1940’s still being subject to dispute in France.

In 1946, Charles De Gaulle ordered the military occupation of Damascus during which French troops destroyed the Syrian Parliament building and killed some 1,000 Syrians. During the war he was the head of the provisional government in Algeria, which in 1945 massacred thousands of Algerian independence protesters in the towns of Sétif and Guelma. The French Algerian government employed systematic torture to against the Arab population. In 1962, De Gaulle granted all French officers in Algeria amnesty guaranteeing they would never face justice for these barbaric, state-sanctioned crimes. In 1968, he extended that amnesty to pro-colonialist terrorist organizations like the OAS.

The French counter-insurgency campaign in Algeria was one of the bloodiest episodes in anti-colonial history, featuring everything from the air bombardment of villages and torture to the forced relocation of millions of people into camps. Charles De Gaulle played a significant role in all this, allowing the war to drag on four more years and only conducting the necessary negotiations belatedly and in secret. Even then, he tried first to retain the Sahara under French rule, but settled for the compromise of being allowed to test nuclear weapons there. Incidentally, it was De Gaulle who started the French nuclear weapons program. His “conservative nationalism” led him to the conclusion that France, too, must have the unilateral power to destroy the human species.

For a more critical perspective on De Gaulle, consider reading John Paul Sartre. “The Frogs who Demand a King” is a place good start.

I’ve always admired Diana Johnstone’s clear headed analyses of world/European/U.S./ China/Israel-Palestine/Russia/… interactions and the motivation of its “players”. She has given some credence to what as been known as French rationalism and enlightenment. (Albeit as an American expat) Think Descartes, Diderot, Sartre…, and She loves France in her own rationalist-humanist way.

I have admired Ms. Johnstone’s work for quite awhile. This enlightening interview spurs me to get a copy of the book and to contribute to Consortium News.

Others may be interested in the two-part video discovered yesterday featuring Douglas Valentine’s analysis of the CIA’s corporate backers and their global choke-hold on governments and their influencers in every region of the world.

Part 1

see:youtu(dot)be/cP15Ehx1yvI

Part 2

see:youtu(dot)be/IYvvEn_N1sE

Not many have the long distance perspective on the world, let alone Europe, that Diana Johnstone has. Great interview!

“Decades of indoctrination in the ideology of “Europe” has instilled the belief that the nation-state is a bad thing of the past. The result is that people raised in the European Union faith tend to regard any suggestion of return to national sovereignty as a fatal step toward fascism. This fear of contagion from “the right” is an obstacle to clear analysis which weakens the left… and favors the right, which dares be patriotic.”

Bingo! A marvelous point indeed!

Quick little example — Bernard Sanders should have worn an American flag pin on his suit during the 2020 Dem primary campaign.

Kudos to CN for featuring this intelligent interview with Johnstone.

A very good analysis. As an American who has relocated to Spain several years ago, I am always disappointed that discussions of European politics always assume that Europe ends at the Pyrenees. Admittedly, Spanish politics is very complicated and confusing. Forty years of an unreconstructed dictatorship have left their mark, but the country´s socialist, communist and anarchic currents never went away. I like to say that the country is very conservative, but at least the population is aware of what is going on. Perhaps what Ms. Johnston says about the French being just worn out, with no stomach for more violent conflict also applies to the Spanish since their great ideological struggle is more recent. The American influence during the Transition (which changed little – as the expression goes: The same dog but with a different collar) was very strong, and remains so. Even so, there is popular support for foreign and domestic policies independent of American and neoliberal control, but by and large the political and economic powers are not on board. I do not think Spain is willing to make a break alone, but would align itself with an European shift away from American control. As Ms. Johnston says, Europe currently lacks leaders willing to take the plunge, but we will see what the coming year brings.

Fascinating perspective from one who is on the scene. This interview over several months that Patrick Lawrence did with Diana Johnstone covers a lot of ground in a short amount of reading time. Well worth your time. From what I have gathered over the years, I tend to agree with almost all of it. I would have liked a comment on De Gaulle and the Algerian War if there was any time for it. I wish you well Ms. Johnstone and Mr. Lawrence.

Thank you Diana, these are valuable insights.

Since WWII the US has itself been occupied by tyrants, using Russophobia to demand power as fake defenders.

1. Waving the flag and praising the lord on mass media, claiming concern with human rights and “Israel”; while

2. Subverting the Constitution with large scale bribery, surveillance, and genocides, all business as usual nowadays.

In the US, the form of government has become bribery and marketing lies; it truly knows no other way.

It may be better that Russia and China keep their distance from the US and maybe even the EU:

1. The US and EU would have to produce what they consume, eventually empowering workers;

2. Neither the US nor EU are a political or economic model for anyone, and should be ignored;

3. Neither the US nor EU produces much that Russia and China cannot, by investing more in cars and soybeans.

It will be best for the EU if it also rejects the US and its “neolib” economic and political tyranny mechanisms:

1. Alliance with Russia and China will cause substantial gains in stability and economic strength;

2. Forcing the US to abandon its “pretensions of world hegemony” will soon yield more peaceful prospects; and

3. Isolating the US will force it to improve its utterly corrupt government and society, maybe 40 to 60 years hence.

“…French philosophy….By constantly attacking, deconstructing, and denouncing every remnant of human “power” they could spot, the intellectual rebels left the power of “the markets” unimpeded, and did nothing to stand in the way of the expansion of U.S. military power all around the world…”

Brilliant. Exactly right.

This was the progenitor to our contemporary I.D. politics which seems to be solely obsessed with vocabulary, semantics and non-economic cultural issues while rarely having a critique of corporate capitalism, militarism, massive inequality and Zionism. And it almost never advocates for robust economic populist proposals like Med4All, U.B.I., debt jubilee, and the fight for $15.

The book is phenomenal. I posted a customer review over on Amazon for this stupendous work. Below is a copy of my review:

(5 stars) One of the most important intellects pens her magisterial lasting legacy

Reviewed in the United States on March 31, 2020

Johnstone’s been an idol of mine ever since I started reading her in the 1990s. She’s clearly proved her worthiness over the decades by bucking the mainstream trend of apologetics for corporate capitalism, neoliberalism, globalism and imperialistic militarism her entire career and this astonishing memoir details it all in what will likely be the finest book of 2020 and perhaps the entire decade.

Her writing style is beyond superb, her grasp of the overarching politico-socio-economic issues that have rocked the world over the past 60 years is as astute and spot-on as you will find from any global thinker. She’s right up there with Michael Parenti, James Petras, John Pilger and Noam Chomsky as seminal figures who have documented and brought light to tens of thousands (millions?) of people across the globe via their writings, interviews and speaking engagements.

Johnstone has never been one to shy away from controversial topics and issues. Why? Simple, she has the facts and truth on her side, she always has. Circle in the Darkness proves all this and more, she marshals the documentation and lays it out as an exquisite gift for struggling working people around the world. From her groundbreaking work on the NATO empire’s sickening war on sovereign Serbia, the dead end of identity politics and trans bathroom debates, to her critique of unfettered immigration and open borders, and her dismissal of the absurd Russsiagate baloney, better than anyone else, Johnstone has kept her intellect carefully honed to the real genuine kitchen table bread and butter issues that truly matter. She recognized before most of the world’s scholars the perils of rampant inequality and saw the writing on the wall as to where this grotesque economic system is taking us all: down a dystopian slope into penury and police-state heavy-handedness, with millions unable to come up with $500 for an emergency car repair or dental bill.

Whenever she comes out with a new article or essay I immediately drop everything and devour it, often reading it twice to let her wisdom really soak in. So too Circle of Darkness is an extremely well written beautiful work that will scream out to be re-read every few years by those with a hunger to know exactly what was going on since the Korean War era through today regarding liberal thought, neocon and neoliberal dominance with its capitalist global hegemony and the take over of Western governments by the parasitic financial elite.

There will never be another Diana Johnstone. Circle in the Darkness will stand as her lasting legacy to all of us.

“As our circle of knowledge expands, so does the circumference of darkness surrounding it”

Albert Einstein

Many Thanks CN, Patrick Lawrence, and Joe Lauria. Once again I must commend CN for picking just the appropriate response to our contemporary dilemma.

The quote above leads Diana Johnstone’s new book and succinctly describes both the universe and our contemporary experience with our digital age. President Kennedy and Charles de Gaulle of France would agree that colonialism was past and that a new world (geopolitical) approach would become necessary, but that philosophy would put them against some great local and world powers. Each of them necessarily had different approaches as to how this might be accomplished. They were never allowed to present their specific proposals on a world stage. Let’s hope a wiser population will once again “see” this possibility and find a way to resolve it…

Well said, Bob

Many Thanks Bob H, it means a lot at this point!

Well over the span of all of those decades, the consistent, inexorable theme seems to be a trend of the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, a small number of individuals, not really states, gaining wealth and power, so everybody else fights over the crumbs, blaming this or that party, alliance, event or whatever, but behind it all there are two flower gardens, indeed the rich are all flowers of their golden garden, and the poor are all flowers of their garden. It’s like the Europeans and the 99 percent in America have all fallen for the myth of the American dream, that if we are just allowed more free, unfettered economic opportunity, it’s just up to us to pick ourselves up by the bootstraps and become a billionaire. The mask competition and fiasco shows the importance of a country simply making things in their own country, not on the other side of the world, it’s not nationalism it’s just a better way to logistically deliver reliable products to the citizens.

Diana Johnstone is brilliant, but has been unfairly and ignorantly condemned because she’s “pro-Putin,” another poisonous result of the entire fraudulent and dangerously stupid “Russiagate” fantasy.

Regarding French colonialism – as I recall the French were especially brutal in their forced withdrawal from Algeria, both toward Algerians in their homeland and to Algerians within France itself.

And the French were hardly willing, non-violent colonialists when being fought by the Vietnamese who wanted to be free of them (quite rightly so).

As for the French in Sub-Saharan Africa – they have yet to truly give up on their presumed right to have troops within these countries. They did not depart any of their colonies happily, willingly – like every other colonial power, including the UK.

And, as for WWII – she seems, in her reminiscences, to have mislaid Vichy France, the Velodrome roundups of French Jews, and so on…..

Ms Johnstone clearly has been looking backwards with rose-tinted specs on when it comes to France.

Reply to Ann,

The movement against the war in Algeria started when the leftist Catholic review La Croix condemned the use of torture by the French State. Public opinion grew rapidly against French Algeria, remained divided but De Gaulle understood that colonialism was a thing of the past (explicitly in famous speeches) so France’s experience in Algeria led to a change in how the French viewed colonialism. De Gaulle in a speech in Phnom Penh explained , based on French experience in Vietnam,that the Americans could not politically win the war in SouthEast Asia. So decolonisation, though a violent process, actually did make the French evolve towards anti colonialism and acceptance of loss of empire. The main social conflicts in France in the sixties and seventies were with Pieds Noirs – the French “citizens” (who had often never lived in France) who came “back” to France when they were ousted out of decolonized Algeria, not with Algerian workers. It is not a “pink lense” to say that France (as other European countries) accepted decolonization in the long term ) while the US has yet to accept to NOT be an imperial power.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a post/neo-colonial mess that is specific and can not be boiled down to the French “can’t give up” Africa – although that is true.

As for Vichy France, Anglo-Saxons who forgave many German industrialists, bankers and politicians who had completely and totally collaborated with their Nazi government, who never particularly condemned every single European governement that collaborated with the Nazis – put a huge emphasis on the Vichy governement. The French population saved more Jews per capita than any other occupied European country (note fascist Italy was not anti Semitic – a paradoxe developed in the book and film The Garden of the Finzi Continis). The Vichy governement was a reality that is condemend by a majority of the French population and De Gaulle did minimize collaboration to reconcile the nation and pull it back together. I think that Diana Johstone’s angle is not idealization of France but criticsm of the American myth that 1) they “saved” Europe when actually Russia did (and paid the price – and took the dividends – namely the occupation of Eastern Europe) 2) that the French were war losers and collaborationists, a portrayal destined to belittle the Gaullist desire for French independence after WWII.

Diana Johnnstone’s lifelong battle is to try to demonstrate that the reality of nations is not the black and white Hollywood movie Americans have fabricated (and often believe in) which amounts to imperial (and war) propaganda. It is for example irrelevant for Americans to call France out on its colonial past: no-one , right or left in France (less so than the British who have kept close ties with the Commonwealth and whose belief in special ties with the “old Empire” explain Brexit in part) still supports colonialism (not to be confused with the debate on whether colonialism was beneficial to populations or not). In other words, the American accusation of France for its imperialism that has totally declined is mainly a tool for its own domination.

That is Diana Johnstone’s angle – not pink lense idealism.

She has always been against American imperialism, which to be fair, since the Korean war has killed more people, committed more atrocities and wrecked havoc in more countries not only than any other country in that same period, but than France every did, Algerian atrocities and French Vietnam war notwithstanding.

In other words, she is trying to put a corrective lense on the way Americans just won’t see how much worse the US has been for decades.

I think her point is: leave other countries alone with their imperfections and tackle your own.

There may be some truth to AnneR’s claim that Ms Johnstone has been looking with rose-tinted specs when it comes to France, but it is highly misleading for her to talk about “the French” regarding Algeria. I spent 1963-64 in Aix-en-Provence teaching at the Institute for American Universities and talked with some of the “pieds-noirs,” (French born in Algeria). After French President Charles de Gaulle decided to relinquish French control over Algeria, having previously reassured the colonial population that “Je vous ai compris” (“I have understood you”), there followed death threats to many French colonizers who had to flee Algeria immediately within 24 hours or get their throats slit – “La valise ou le cercueil” (the suitcase or the coffin). In the fall of 1961, I saw Parisian police stations with machine-gun armed men behind concrete barriers, as an invasion by the colonial French paratroopers against mainland France was expected. The “Organisation Armée Secrète,” OAS, (Secret Armed Organization) of the colonial powers, threatened at the time to invade Paris. As an aside, giving a sense of the anger and passion involved, when the death of John F.Kennedy in November 1963 was announced in the historic, right-wing café in Aix, Les Deux Garçons, a huge cheer went up when the media announcer proclaimed “Le Président est assassinée. Only, that was because they thought de Gaulle was the president in question. A huge disappointment when they heard it was President Kennedy. To get a sense of the whole situation regarding France and Algeria I recommend Alistair Horne’s “A Savage War of Peace.”

“They did not depart any of their colonies happily”

Some hold that they never departed, but mutated tools including CFA zones and “intelligence” relations in furtherance of “changing” to remain qualitatively the same.

Just as “The United States of America” is a system of coercive relations not synonymous with the political geographical area designated “The United States of America”, the colonialism of former and present “colonial powers” continues to exist, since the “independence” of the colonised was always, and continues to be, framed within linear systems of coercive relations, facilitated by the complicity of “local elites” on the basis of perceived self-interest, and the acquiescence of “local others” for myriad reasons.

Despite the “best” efforts of the opponents and partly in consequence of the opponents’ complicity, the PRC and the Russian Federation like “The United States of America” are not synonymous with the political geographical areas designated as “The People’s Republic of China and The Russian Federation”, are in lateral process of transcending linear systems of coercive relations and hence pose existential threats to “The United States of America”.

The opponents are not complete fools but the drowning tend to act precipitously including flailing out whilst drowning; encouraging some to dispense with rose- tinted glasses, despite such accessories being quite fashionable and fetching.

“….. their colonies ……”

Perception of and practice of social relations are not wholly synonymous.

A construct whose founding myths included liberty, egality and fraternity – property being discarded at the last moment since it was judged too provocative – experienced/experiences ideological/perceptual oxymorons in regard to its colonial relations, which were addressed in part by rendering their “colonies” department of France thereby facilitating increased perceptual dissonance.

Like many, Randal Marlin draws attention below to the perceptions and practices of the pied-noir, but omits to address the perceptions and practices of the harkis whom were also immersed in the proselytised notion of departmental France, and to some degree continue to be.

This understanding continues to inform the practices and problems of the French state.

The analysis is very much inspired from “Comprendre l’Empire” by Alain Soral.

…which I never read.

Was Alain Soral inspired by me?

Do not fail to read this interview in its entirety. Ms Johnstone analyzes and describes many issues of national and global importance from the perspective of an USA expat who has spent most of her career in the pursuit of what may be termed disinterested journalism. Whether one agrees or disagrees…in whole or in part…the perspectives she presents, particularly those which pertain to the demise (hopefully) of the American Empire are worthy of perusal. Remember that this is not a polemic; it’s a memoir of a lifetime devoted to reporting and analyzing and discussion of most of the significant issues confronting global…and national…politics and their social ramifications. And a big thanks to Patrick Lawrence and Consortium News for posting the interview.

Brilliant insights and overview and marvelous interview.

Diana Johnstone is one of the most intelligent, clear-minded and honest observers of international politics today, and her book “Circle in the Darkness” – which expands on the topics and insights touched on in this interview – is certainly among the best and most compelling books I have ever read, putting the events of the last 75 years into objective context and focus (normally something which only historians can do, if at all, generations after the fact).

After reading Circle in the Darkness, I have ordered and am now reading her books on Hillary Clinton (Queen of Chaos) and the Yugoslav wars (Fool’s Crusade), which are very worthwhile and important. I would recommend that her many articles over the years, appearing in such publications such as In These Times, Counterpunch and Consortium News, be reprinted and published together as an anthology. Through Circle in the Darkness, we have Diana Johnstone’s “Life”, but it would be good also to have her “Letters”.

Interesting comparison between the aspirations of De Gaulle and Putin.

“Having a sense of history, de Gaulle saw that colonialism had been a moment in history that was past. His policy was to foster friendly relations on equal terms with all parts of the world, regardless of ideological differences. I think that Putin’s concept of a multipolar world is similar. It is clearly a concept that horrifies the exceptionalists.”

Agree with Johnstone.

“Having a sense of history, de Gaulle saw that colonialism had been a moment in history that was past. ”

Mr. de Gaulle like other “leaders” of colonial powers did understand that the moment of overt coercive relations of colonialism had passed and that colonialism to remain qualitatively the same, required covert coercive relations facilitated by the complicity of local “elites” on the basis of perceived self-interest.

The exceptions to such strategies lay within constructs of settler colonialism which were addressed primarily through warfare – “The United States of America”, Vietnam/Laos/Cambodia, Indonesia, Algeria, Kenya, Rhodesia, Mozambique, Angola refer – to facilitate such future strategies.

“I think that Putin’s concept of a multipolar world is similar.”

As outlined elsewhere the concept of a multi-polar world is not synonymous with the concept of colonialism except for the colonialists who consistently seek to encourage such conflation through myths of we-are-all-in-this-togetherness.