The mounting fear as coronavirus spreads is reminiscent of poliomyelitis. It’s instructive to remember what it took to nearly eradicate polio and a reminder of what we can do when faced with a common enemy, says Carl Kurlander.

(www.apimages.com)

By Carl Kurlander,

University of Pittsburgh

The fear and uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus pandemic may feel new to many of us. But it is strangely familiar to those who lived through the polio epidemic of the last century.

Like a horror movie, throughout the first half of the 20th century, the polio virus arrived each summer, striking without warning. No one knew how polio was transmitted or what caused it. There were wild theories that the virus spread from imported bananas or stray cats. There was no known cure or vaccine.

For the next four decades, swimming pools and movie theaters closed during polio season for fear of this invisible enemy. Parents stopped sending their children to playgrounds or birthday parties for fear they would “catch polio.”

In the outbreak of 1916, health workers in New York City would physically remove children from their homes or playgrounds if they suspected they might be infected. Kids, who seemed to be targeted by the disease, were taken from their families and isolated in sanitariums.

In 1952, the number of polio cases in the U.S. peaked at 57,879, resulting in 3,145 deaths. Those who survived this highly infectious disease could end up with some form of paralysis, forcing them to use crutches, wheelchairs or to be put into an iron lung, a large tank respirator that would pull air in and out of the lungs, allowing them to breathe.

Ultimately, poliomyelitis was conquered in 1955 by a vaccine developed by Jonas Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh.

In conjunction with the 50th anniversary celebration of the polio vaccine, I produced a documentary, “The Shot Felt ‘Round the World,” that told the stories of the many people who worked alongside Salk in the lab and participated in vaccine trials. As a filmmaker and senior lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh, I believe these stories provide hope in the fight to combat another unseen enemy, coronavirus.

Pulling Together as a Nation

Before a vaccine was available, polio caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis a year in the U.S. It was the most feared disease of the 20th century. With the success of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk, 39, became one of the most celebrated scientists in the world.

He refused a patent for his work, saying the vaccine belonged to the people and that to patent it would be like “patenting the Sun.” Leading drug manufacturers made the vaccine available, and more than 400 million doses were distributed between 1955 and 1962, reducing the cases of polio by 90 percent. By the end of the century, the polio scare had become a faint memory.

Developing the vaccine was a collective effort, from national leadership by President Franklin Roosevelt to those who worked alongside Salk in the lab and the volunteers who rolled up their sleeves to be experimentally inoculated.

Sidney Busis, a young physician at the time, performed tracheotomies on two-year-old children, making an incision in their necks and enclosing them in iron lung to artificially sustain their breathing. His wife Sylvia was terrified that he would transmit polio to their two young sons when he came home at night.

In the Salk lab, a graduate student, Ethyl “Mickey” Bailey, pipetted by mouth – pulling liquid up thin glass tubes – live polio virus as part of the research process.

My own neighbor, Martha Hunter, was in grade school when her parents volunteered her for “the shot,” the experimental Salk vaccine that no one knew if it would work.

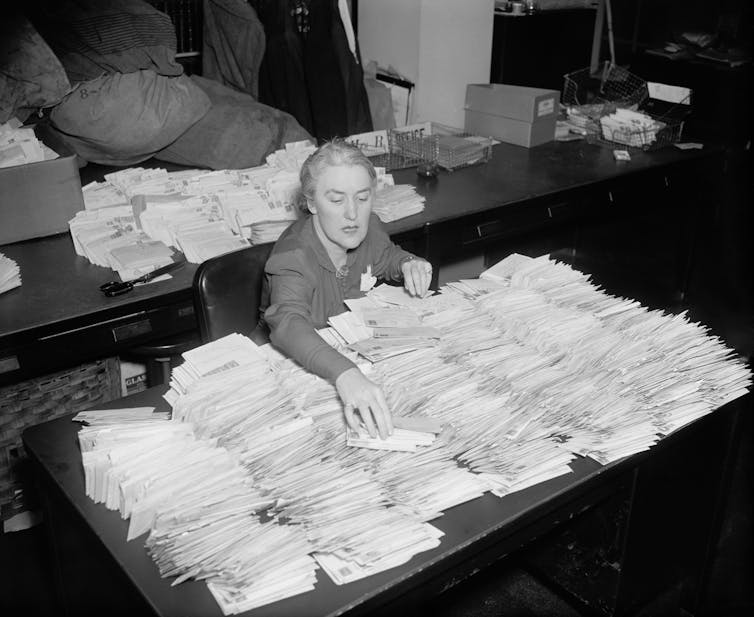

President Roosevelt, who kept his own paralysis from polio hidden from the public, organized the nonprofit National Institute of Infant Paralysis, later known as the March of Dimes. He encouraged every American to send dimes to the White House to support treating polio victims and researching a cure. In the process, he changed American philanthropy, which had been largely the domain of the wealthy.

(Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com)

That was a time, said Salk’s oldest son, Dr. Peter Salk, in an interview for our film, when the public trusted the medical community and believed in each other. I believe that’s an idea we need to resurrect today.

What it Took to End Polio

Jonas Salk was 33 when he began his medical research in a basement lab at the University of Pittsburgh. He had wanted to work on influenza but switched to polio, an area where research funding was more available. Three floors above his lab was a polio ward filled to capacity with adults and children in iron lungs and rocking beds to help them breathe.

There were many false leads and dead ends in pursuing remedies. Even President Roosevelt traveled to Warm Springs, Georgia, believing that the water there might have curative effects. While most in the scientific community believed that a live polio virus vaccine was the answer, Salk went against medical orthodoxy.

He pursued a killed virus vaccine, trying it first on cells in the lab, then monkeys and, next, young people who already had polio. There were no guarantees this would work. Ten years earlier, a different polio vaccine had inadvertently given kids polio, killing nine of them.

In 1953, Salk was given permission to test the vaccine on healthy children and began with his three sons, followed by a vaccination pilot study of 7,500 children in local Pittsburgh schools. While the results were positive, the vaccine still needed to be tested more widely to gain approval.

In 1954, the March of Dimes organized a national field trial of 1.8 million schoolchildren, the largest medical study in history. The data was processed and on April 12, 1955, six years from when Salk began his research, the Salk polio vaccine was declared “safe and effective.” Church bells rang and newspapers across the world claimed “Victory Over Polio.”

Vaccinations and Global Health

In adapting our documentary for broadcast on the Smithsonian Channel, we interviewed Bill Gates, who explained why the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation had made eradicating polio worldwide a top priority.

Vaccines, he said, have saved millions of lives. He joined the World Health Organization, UNICEF, Rotary International and others to help finish the job started by the Salk vaccine, eradicating polio in the world. This accomplishment will free up resources that will no longer have to be spent on the disease.

(AP Photo/K.M. Chaudary)

Up until now, smallpox is the only infectious disease we have ever eliminated. But the global infrastructure that the polio eradication effort has put in place is helping to fight other infectious diseases also, such as Ebola, malaria and now coronavirus. On Feb. 5, 2020, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced it would provide US$100 million to improve detection, isolation and treatment efforts and accelerate the development of a vaccine for the coronavirus.

These are frightening times as the coronavirus spreads in ways reminiscent of poliomyelitis. It’s instructive to remember what it took to nearly eradicate polio and a reminder of what we can do when faced with a common enemy. On Oct. 24, 2019, World Polio Day, WHO announced there were only 94 cases of wild polio in the world. The success of the polio vaccine launched a series of vaccines that negated many of the effects of infectious disease for the second half of the 20th century.

At the end of our film, Salk’s youngest son, Dr. Jonathan Salk, recounted how his father wondered every day why we couldn’t apply the spirit of what happened with the development of the polio vaccine to other problems, such as disease or poverty. In fighting coronavirus, perhaps the citizens and governments of the world will rise to the occasion and demonstrate what is possible when we work together.

Carl Kurlander, is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Great article. I published one on the fight against polio on my blog today, see: americansystemnow.com, which had the focus of FDR’s leadership in this fight. Your readers might find it interesting. see: americansystemnow.com/how-fdr-conquered-polio-twice/

Nancy Spannaus

Mr Kurlander: I am a political organizer with the LaRouche organization, Peter Bowen is a friend of mine. Before we got hit by the Corona virus, I kept running into people who are refusing the get their kids vaccinated. I have always thought this was wrong, not only because they can potentially can get and spread a disease, but if we stop vaccinations diseases like polio could come back. I’m sure you recall the big measles cases of the last several years. My cousin contracted polio. I contracted measles at the age of 6 and nearly died. Our neighbor, who was pregnant, contracted a mild case of measles and her child was born with a cleft palate. Now, we have a pandemic which can decimate millions of people, unless we pull together all our forces, in every country and knock it out. I believe we must take the whole world into our heart and do whatever is necessary to save people, as if they were our own family and friends. So, I think that Mr. Bowen’s note to you should be taken in earnest by everyone who comes in contact with it. We need to kill the disease, without killing the economy, and President Trump should shut down the Stock Market and begin to implement Glass-Steagall. More needs to be done, and people need this information. Thank you for your article and work on Polio, this history is important to know.

Best Regards and Stay safe,

Denise Bouchard Ham

Remember that the Salk vaccine was used in other countries too. I had it at 14 years old in Australia in 1955. In those days the USA actually had someone not interested in grabbing money as we see now, but Salk gave the vaccine to the world, free of patents. Quite a change from the present “keep up the sanctions and enmity to countries who dare to be sovereign”.

I remember polio. I have an orthopoedic disability, and my doctor was one of the people who developed the field of pediatric orthopoedics, mostly to treat kids who had polio. It was in the early 1960s–I would have been 11 or 12–when the mass vaccination campaign came to my hometown in northern California. A couple who lived next door had lost their small son to polio. The father went door-to-door on our street, talking to dads, telling about his son, and urging all the men to take their families and get vaccinated. A woman named Mary, who lived down the street, had contracted polio in her early 30s. She had 4 kids, the oldest about my age (5th grade.) Mary’s oldest son pushed her wheelchair up and down our street, ran up to our doors, and asked moms to come talk to Mary. She urged them to get vaccinated and to make sure all their kids were too. Mary’s kids talked to every class in our school about polio, their mom, and the vaccination campaign, and told all us kids to get ourselves and our parents and friends vaccinated. The vaccination campaign involved going to the school auditorium three times, for three months in a row. My parents and siblings and I, along with everyone on our street, walked to the school together. At the door to the auditorium, the parents of that little boy from next door stood, welcoming all of us. The boy’s mother had tears pouring down her face, as her friends and neighbors told her they’d come to be vaccinated in memory of her son, who had died of that terrible disease.

It may have been the first time that she and her husband had been able to grieve for their son, with the support of their community. When the vaccination campaign was over, our street had a 100% vaccination rate. At the end of the campaign President Lyndon Johnson got on the radio (we didn’t have a TV) and declared that polio had been conquered, that never again would our children die and be paralyzed by this horror. Church bells rang, factory whistles blew. On my block, people organized an impromptu potluck celebration in the middle of the street. People hugged and cried. We, the American people, had done this together. In the years since I’ve come to know many polio survivors who are about my age: my first college roommate, my fellow orthopoedics patients, my next-door neighbor. All of them are in their mid- to late-60s or older now. Most younger people have never even seen pictures of iron lungs, never mind seen wards of them, as I’ve done. I guess most American doctors have never seen a case. But that doesn’t mean we can forget Dr Salk, the vaccination campaign, or the polio survivors. That doesn’t mean that we can forget what we Americans can do, when we come together, and when we have the leadership we need.

How different America is today, with drug makers trying to make as much money as possible, as quickly as possible—and with such little concern for the lives of victims. Maybe the fact that polio came so close to the end of WW II, maybe that helped people to gather and help more readily. Nowadays, it is so confusing to see parents afraid of vaccines and willing to pollute the world again, with diseases that were once thought to be eradicated.It seems that as awful as WW II was, it somehow brought the nation together——-I wish that gathering together would happen with the coronavirus——people supporting and working together ( and with no thought of a money reward) to make the world safe from the current hypocrisy.

I am old enough to vividly remember the polio epidemic that closed schools, swimming pools et al and resulted in my sister and my aunt both getting polio. What I do not remember is a war between the administration and reality, sanity and progress.

Have we fallen this far?

I was a three year old living in a Pittsburgh suburb when the Salk vaccine was approved. My brother was an infant. I have a vague memory of sitting with my parents, or a parent, in the waiting room of our doctor awaiting our turn. My father, a 1949 Pitt grad on the GI bill, looked at Jonas Salk as the American hero he truly was. It would be like “patenting the sun.” That kind of ethical stance is impossible to even imagine today. Thank you for keeping this history alive. And, thank you Dr. Salk, and your colleagues are the University of Pittsburgh, then a private institution that could have used the revenue from a patent on that vaccine- it became a state university in the mid 1960s for financial reasons. The Greeks sing of the dead, May your memory be eternal. Yours will be.

I recall those iron lungs. When you see one, you never forget it. A much more tear jerking time than this current virus. So if it took a daring scientist then to come up with a solution, with the people naive although not quite ignorant as now, can’t we stop and think straight to come up with a handle on COVID-19? It usually takes someone like an Assange to come up with innovation.

Thank you Mr. Kurlander for this summary of the campaign against polio. No doubt the reason that “we couldn’t apply the spirit of … development of the polio vaccine to other problems, such as disease or poverty” is that the public was less indoctrinated then by the scoundrels who rise in our unregulated market economy to power in government and mass media. The scoundrels are aggrandized by broad suffering of others, and respond only when afraid of public rejection, rebellion, or the disease itself. If they did not have elderly relatives they would doubtless do nothing at all about Covid19, and will protect the poor last if at all.

Let’s hope that this time broad immunization doesn’t take 7 years, after the 2 years expected to develop and test a vaccine.

Mr. Kurlander,

The solution to the crisis is already available, although a vaccine still is needed as is the rebuilding of health infrastructure and the building of real health infrastructure is all underdeveloped countries. But that is not done because the financial resources of the world are, in large part, controlled by maniacal speculators who have no interest in defending human life. The solution is to suspend trading on the financial markets, sort out the retirement savings and investments of citizens to protect them, impose GlassSteagall legislation again, create a national banking structure that can emit credit for actual physical development (hospitals, medical equipment, and other long overdue vast infrastructure (flood control, high speed rail, etc.), and drive it all forward with the spin offs from nuclear fusion research and space exploration. In other words, do what Mr. Lyndon LaRouche has be advocating for the past 50 years!

Stay safe,

Peter Bowen