Issa Sikiti da Silva reports on the struggles for many in the Sahel, the area between the Sahara in the north and the Sudanian Savanna in the south where temperatures are rising faster than anywhere else on Earth.

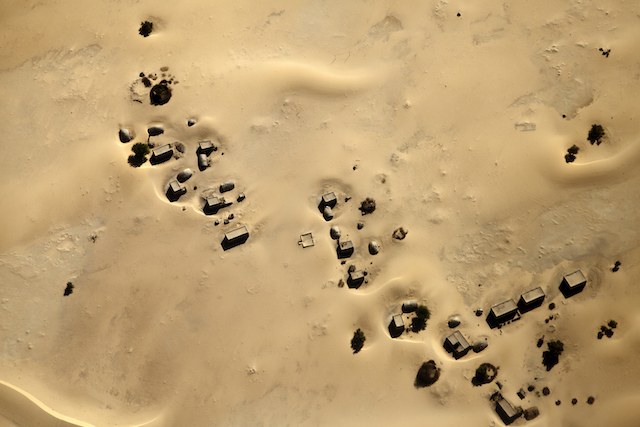

Aerial view of settlements in area of desert near Timbuktu, north of Mali. (UN/Marco Domino)

By Issa Sikiti da Silva

in Bamako, Mali & Cotonou, Benin

Inter Press Service

Abdoulaye Maiga proudly displays an album showing photos of him and his family during happier times when they all lived together in their home in northern Mali. Today, these memories seem distant and painful.

“We lived happily as a big family before the war and ate and drank as much as we could by growing crops and raising livestock,” he tells IPS.

“Then the war broke out and our lives changed forever, pushing us southwards, finally settling in the region of Mopti. Then we went back home in 2013 when the situation stabilized,” Abdoulaye explains.

In 2012, various groups of Tuareg rebels grouped together to form and administer a new northern state called Azawad. The civil strife that resulted drove many from their homes, with communities often fleeing with their livestock, only to compete for scarce natural resources in vulnerable host communities, according to the United Nations.

- In Mali, three-quarters of the population rely on agriculture for their food and income, and most are subsistence farmers, growing rainfed crops on small plots of land, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the UN.

After the security situation began to improve in 2013, many returned home to rebuild their lives and livelihoods.

But soon it was the turn of the expanding Sahara Desert, drought and land degradation that became the next driver of their displacement.

“As time went by, the land became useless and we found ourselves having no more land to work on. Nothing would come out that could feed us, and our livestock kept dying due the lack of water and grass to eat,” Abdoulaye recalls.

>>Please Donate to Consortium News’ Fall Fund Drive<<

“Drought across the Sahel region, followed by conflict in northern Mali, caused a major slump in the country’s agricultural production, reducing household assets and leaving many of Mali’s poor even more vulnerable,” FAO says.

“We used to move up and down with our livestock, looking for water and grass, but most of the times we found none. Life was unliveable. The Sahara is coming down, very fast,” Abdoulaye says emotionally.

In the end, the Maiga family had to leave their home and broke up; Abdoulaye and his brother Ousmane heading to Benin’s commercial capital Cotonou in 2015, after a brief stint in Burkina Faso, as the rest of their family headed for Mali’s capital, Bamako.

Malian girls in Kidal, North of Mali. (INUSMA/Marco Dormino)

Creeping Desertification

The UN says nearly 98 percent of Mali is threatened with creeping desertification, as a result of nature and human activity. Besides, the Sahara Desert keeps expanding southward at a rate of 48 km a year, further degrading the land and eradicating the already scarce livelihoods of populations, Reuters reported.

The Sahara, an area of 3.5 million square miles, is the largest ‘hot’ desert in the world and home to some 70 species of mammals, 90 species of resident birds and 100 species of reptiles, according to DesertUSA. And it is expanding, its size is registered at 10 percent larger than a century ago, LiveScience reported.

The Sahel, the area between The Sahara in the north and the Sudanian Savanna in the south, is the region where temperatures are rising faster than anywhere else on Earth.

The cost of land degradation is currently estimated at about $490 billion per year, much higher than the cost of action to prevent it, according to UNCCD recent studies on the economics of land desertification, land degradation and drought.

Roughly 40 percent of the world’s degraded land is found in areas with the highest incidence of poverty and directly impacts the health and livelihoods of an estimated 1.5 billion people, according to the UN.

In a country where 6 million tonnes of wood is used per year, reports say Malians are mercilessly smashing their already-fragile landscape, bringing down 4,000 square kilometres of tree cover each year in search for timber and fuel.

Lack of rain has also been making matters worse, especially for the cotton industry, of which the country remains the continent ’s largest producer, with 750,000 tonnes produced in the 2018 to 2019 agriculture season. Environmentalists believe Mali’s average rainfall has dropped by 30 percent since 1998 with droughts becoming longer and more frequent.

Conflict Over Resources

Paul Melly, Chatham House Africa consultant, tells IPS that desertification reduces the scope for agriculture and pastoralism to remain viable.

“And of course, that may lead a few disenchanted members of the population, particularly young men, to be attracted by alternative livelihood options, including the money that can be offered by trafficking gangs or terrorist groups,” he says.

Ousmane echoes Melly’s sentiments, saying: “The temptation is too much when you live in desertification-hit areas because you don’t get enough food to hit and water to drink.

“That’s where the bad guys start showing up on your door[step] to tell you that if you join them, you will get plenty food, water and pocket money. The solution is to run away, as far as you can to avoid falling into that trap.”

Consequently, Ousmane and Abdoulaye sold the few remaining animals the family had so they could leave the country.

In Burkina Faso they hoped to find work in farming.

However, they were not always welcomed.

“We could feel the resentment from locals, so I told my brother we should leave before it gets ugly because there were already some tensions between local communities over what appeared to be land resources,” he says.

Chatham House’s Melly confirms this: “There is no doubt that the overall context, of increasing pressure on fragile and sometimes degrading natural resources, is a contributory factor to the overall pressures in the region and, thus, potentially, to tension.”

Like elsewhere on the continent, severe environmental degradation appears to be among the root causes of inter-ethnic conflicts.

Using the Darfur region as a case study, the Worldwatch Institute says: “To a considerable extent, the conflict is the result of a slow-onset disaster—creeping desertification and severe droughts that have led to food insecurity and sporadic famine, as well as growing competition for land and water.”

What is Being Done?

Projects such as the UN Convention to Combat Desertification’s Land Degradation Neutrality project aimed at preventing and/or reversing land degradation are some of the interventions to stop the growing desert.

- Another large that aims to wrestle back the land swallowed by The Sahara is the Great Green Wall (GGW), an $8 billion project launched by the African Union (AU) with the blessing of the UNCCD, and the backing of organizations such as the World Bank, the European Union and FAO.

- Since its launch in 2007, major progress has been made in restoring the fertility of Sahelian lands.

- Nearly 120 communities in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have been involved in a green belt project that resulted in the restoration more than 2,500 hectares of degraded and drylands, according to the UNCCD.

- More than 2 million seeds and seedings have also been planted from 50 native species of trees.

Double Threats

But there remain gaps and many in Mali still remain affected.

Community leader Hassan Badarou spent several years teaching Islam in rural Mali and Niger. He tells IPS Mali has a very complex situation.

“It is not easy to live in these areas. People there face double threats. It is double stress to flee from both armed conflict and desertification. And such people need to be welcomed and assisted, and not be seen as a threat to locals livelihoods.

“That is why we used to preach tolerance and solidarity wherever we went, to avoid a situation whereby local communities would feel that their meagre resources are under threat from newcomers. There should be a dialogue, an honest and frank dialogue when communities take on each other over land and water resources,” he advises.

Against the expanding Sahara, all are equal. Fadimata, an internally displaced person from northern Mali, tells IPS that climate change is affecting everyone in the Sahel, including terrorists.

“I saw with my own eyes how a group of heavily-armed young men came to a village, looking for food.

“They said they wanted to do no harm, but wanted something to eat. Of course, we were very scared, but the villagers ended up putting something together for these poor young men. They sat down and ate, and drank plenty of water and left afterwards. I think it is better that way than to kill villagers and steal their food, livestock and water.”

Issa Sikiti da Silva is a correspondent for Inter Press Service.

This article is from Inter Press Service

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will be removed. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments.

>>Please Donate to Consortium News’ Fall Fund Drive<<

A good summary of the various forces at work in the region and their social consequences.

I think it important to emphasize the people’s consumption of their forests. That’s where perhaps outsiders could really help.

Wouldn’t it be nice if the United States worked on problems like this instead of killing people and destroying still more things in the Middle East?

It would be nice to have included information about the Great Green Wall project.

The reference link is dead.

The US has indeed consistently failed since WWII to rise to its humanitarian potential and responsibility.

We could have lifted half of humanity from poverty, instead of reducing regions to rubble on mad pretexts.

Had we built the roads, schools, and hospitals of the developing world, we would have no security problems.

We used NATO and the UN to get bribes to US politicians, and neutered them as institutions of progress.

We could still re-purpose 80% of the MIC to foreign aid with no economic loss and far greater security.

That will not happen because all US politicians and mass media serve corrupt economic powers.

The world will have to completely embargo the US, forcing its oligarchy to steal directly from the People.

Only when the People see that they must pay for organized corruption, will they restore democracy.

That will take a century, but the black record of US exploitation and wars for bribes can never be expunged.

There is historical evidence that the Sarah and Sahel once the cradle of more modern human ancestors such as Homo erectus has experienced many cycles of humid and arid ecosystems. There is a theory that during Marine Isotope Stage 6 the region became uninhabitable due to a prolonged period of glaciation (ice age) lasting tens of thousand of years. Marine sediments show evidence that due to hostile environmental conditions the population of early humans was driven to near extinction during this time as they were driven southward to find food. We all share a common ancestor or ancestors dating to this bottleneck in the evolution of humans caused by environmental climate change.

This was in part exacerbated by the precession of the earth’s axis which has a 26000 year cycle. Think of it as a wandering polar axis like a spinning top that both spins on its axis and wobbles slowly around a central point.

Now add into the mix the global climate trend and the various forcing factors in the climate including the dimming of the solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface due to pollution as well as the buildup of greenhouse gasses and there lies the problem..

All of these scientific observations adds up to spell trouble for the Sahel with increasing drought and the unsustainable toehold for the people there.

What can be done? There is little that can be done as long as we keep on keeping on with our modern industrialized planet that is a slave to fossil fuels.

We are heading toward a new big crunch with human survival hanging in the balance on many fronts. What happens in Africa will tell the tale of today and tomorrow just like it did thousands of years ago. We surely do not collectively know what fate lies ahead but climate change in Africa will play a part in determining our survival into the future as one species that is ill equipped to handle the coming changes in our environment.

The Europeans, NATO, et al have a lot to answer for in their Libya campaign, since apart from destroying the most prosperous State and the highest standard of living of any in Africa – and the most beneficial welfare system for its citizens, whether in health, education, housing, or old age compensation – turning Libya into a failed State at war with itself, and with the West and the West’s foreign proxies, they also destroyed what would have been the larger water delivery system in the world (one built without U.S. contractors), just before it could be hooked up- a water system that would have allowed Libya and its neighbors to survive and prosper during the droughts, and would have enabled ‘the desert to bloom’, since it would have tapped into water aquifers under the Sahara said to contain 4 billion gallons of water. So much for the US’ and EU’ hypocritical application of “democracy, human rights and ‘Open Society’ “. What they did to Libya was an unspeakable war crime, just as what they’ve done to Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen.

It is very good to see CN confront this. The political causes and the political effects of desertification are worthy of our time in consideration.

Efforts in reclaiming places like Yemen, Libya, or Syria get vastly disrupted by violence that is overwhelmingly Western and by the black and grey market crime and violence that inevitably follow. Widening ecological destruction is a further cost of current Western foreign policy and of economic colonialism in general.

Efforts to plant trees are very good, but are mostly still in what might be called a learning stage. It costs more effort per acre to arrange that water stay in the soil and to arrange a livelihood for those who will tend the trees, but there is a big advantage to these as well: the trees thrive rather than dying.

This has been done in very dry lands (the interested may search for Geoff Lawton and Greening the Desert, where this is documented). It has been done on a very large scale in the source lands of China’s Yangtze River (and here the interested may search for John Liu and Lessons of the Loess Plateau). Great changes in agriculture have been done in the face of sudden economic emergency as well (and here the example is more difficult to track down, but a prime example is the Organoponics movement in Cuba after the fall of the Soviet Union, el moviemiento agroponico during what is called el period especial).

This involves productive trees, bushes, vines, gardens, and in the case of dry lands particularly carefully limited rotational grazing of grasslands to reduce fire fuel load and implement ecosystems that include and care for humans.

The methodology to do this exists, and the labor force would be adequate were it oriented to task.

As to orienting people to task, there are various ways forward and various political problems, as usual. But there are no real viable alternatives to accomplishing it.

The Sahel southward migration of pluviogenic structures had been observed since the climatic shift of the 1970s and correlated with the rise of average atmospheric pressures, consequence of stronger and more powerful expulsion of polar air masses.

But the situation is complex as per this article:

Analyse rétrospective de l’évolution climatique récente en Afrique du Nord-Ouest

The last paragraph says quite a lot. Thank you very much for this.