Amid all the 50th anniversary commemorations of Apollo 11, As`ad AbuKhalil finds little mention of the pioneering contributions of the Soviet space program.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

It was Noam Chomsky who once said that NASA was the biggest propaganda scam of the 20th century, or words to that effect.

It was Noam Chomsky who once said that NASA was the biggest propaganda scam of the 20th century, or words to that effect.

When I was 10, my American school in Beirut took us on a field trip (it was a few steps from our school really) to a building at the American University of Beirut where small rocks from the moon were displayed behind a glass cover (this was shortly after the 1969 landing on the moon). The rocks were on their own international tour while the State Department arranged a separate global road show for the three returning astronauts.

When Michael Collins (one of the three astronauts of Apollo 11) retired, he joined the propaganda arm of the State Department, while both Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin joined the corporate world. (Armstrong first made full tenured professor at the University of Cincinnati but he was disillusioned when collective bargaining set in among the faculty).

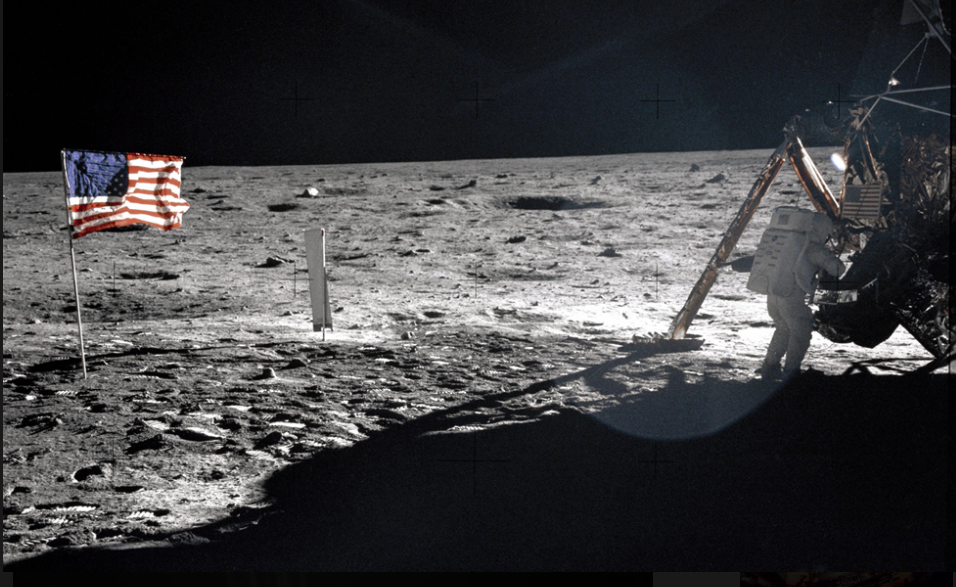

Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong in one of the few photos showing him during the moonwalk. (NASA)

The story of the moon landing entwines with the history of the Cold War. Amid all the self-congratulatory commemorations of Apollo 11 on its 50thanniversary this month, not much is being said in the U.S. about the pioneering contributions of the Russian space program. Few in the U.S. know the name of the first man to travel in space (a Soviet), the first person to walk in space (a Soviet), or the first female astronaut (a Soviet cosmonaut, the word “astronaut” was derived from the Russian term). The entire U.S. space program was set up to compete with, and defeat, the Soviet program.

The chronology of the moon landing project was solely launched in response to the Soviet space achievements. American exploration of space was about domination of the Earth. President Lyndon Johnson (a big advocate of space exploration) said: “control of space means control of the world.” And President John Kennedy’s famous speech at Rice University in 1962, mixed rhetoric of the moon program with the struggle against communism and even praise for Christianity. People forget that President Dwight Eisenhower threatened to nuke China in 1953, and U.S. lawmakers would casually threaten to drop atomic bombs on the U.S.S.R. at the time.

Yuri Gagarin, First Man in Space

Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, in 1964. (SAS Scandinavian Airlines via Wikimedia Commons)

The first space flight by Yuri Gagarin in April of 1961 triggered the U.S. moon landing project. Alan Shepard was sent into space (for a mere 15 minutes) less than a month after Gagarin’s trip. Internal government memos show tremendous agitation and nervousness about Soviet scientific successes. And it was in May of 1961, that Kennedy gave his speech in Congress in which he declared the U.S. plan to send a man (not women) to the moon and returning him safely to Earth. The moon landing project was enormous by any measure: it cost more than $20 billion (more than $200 billion in today’s value). More than 400,000 Americans were involved in the project.

Eisenhower was faulted for not exhibiting enthusiasm for the space program. It is possible that his attitude was influenced by his critique of the military-industrial complex. The moon project was a mega illustration of that complex: corporations in different fields around the U.S. were involved as were departments of physics, chemistry, engineering and medicine in the big research universities. The entire military was utilized by the program, as were intelligence agencies. The CIA was instrumental in monitoring and stealing Soviet space secrets, including the theft of the design of their satellites.

The genius of the American plan was in organization and management. NASA was run like a military institution; factionalism and squabbles were not permitted. The U.S. was able to quickly catch up and then surpass the U.S.S.R. in the space race due to many factors.

Factors Favoring the U.S.

No. 1) The Soviet space program was more democratic than the American counterpart, and splits and feuds between various scientists were common there, as Assiri Siddiqi describes in his book “The Soviet Union and the Space Race.” NASA had a centralized leadership which issued commands that had to be obeyed. Obedience was made easier by the recruitment of astronauts from the military services (all three members of Apollo 11 served in the military and Armstrong and Aldrin fought in Korea). The Soviet political leadership did not respond to the demands and needs of the brilliant Soviet scientists, especially its chief rocket scientist, Sergei Korolev.

No. 2) The U.S. invested heavily in the space program after Kennedy’s speech about the project, while Soviet political support, in a couple of years, had begun to waver.

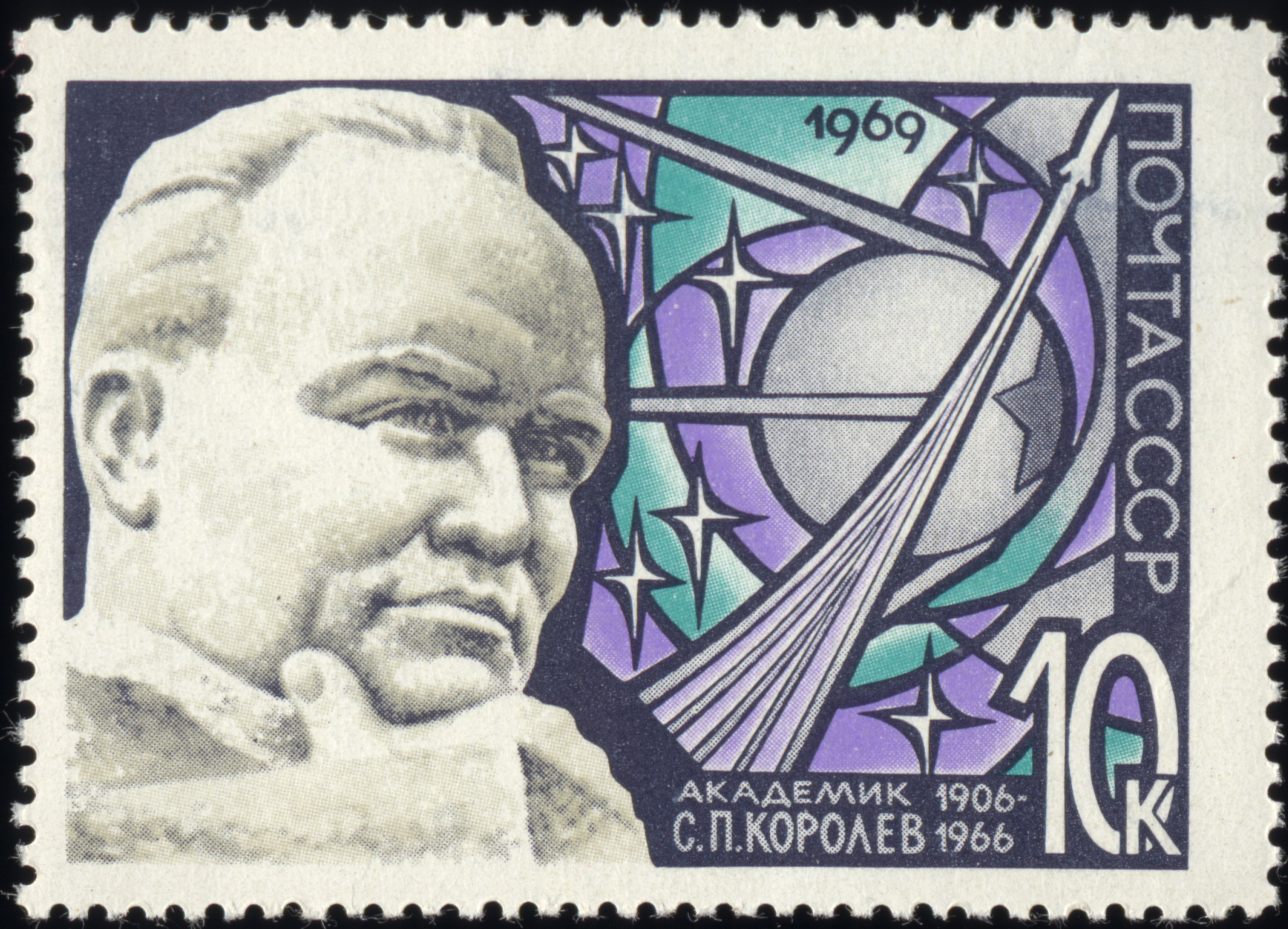

No. 3) Luck played a role. Korolev died from a heart attack in 1966 (he was so valuable to the Soviet Union that his real name was not released until after his death).

No. 4) The U.S. took risks in its development of the program, and even risked the lives of its men (like the faulty design of the hatch door which prevented the crew from opening it when a spark caused the oxygen to ignite, which caused the death of the three astronauts of Apollo 1.)

No. 5) The Nazi rocket scientist Wernher von Braun.

1969 Soviet Union postage stamp of Sergei Korolev. (Wikimedia Commons)

If the Soviet Korolev was the father of the Soviet space rocket program, the America rocket program had no American father. It was von Braun who played the leading role in the design of the space rockets (and he borrowed from Soviet designs when the U.S. was lagging far behind).

It is rather ironic that the U.S. and Israel raised a hue and cry in the 1960s about the presence of a few German scientists in Egypt, given a secret U.S. intelligence program to bring 1600 Nazi scientists, operatives and engineers from Germany and protect them from capture by Nuremberg war crimes prosecutors and later Nazi hunters. (For more on this, see Linda Hunt’s book, “Secret Agenda: The United States Government, Nazi Scientists, and Project Paperclip, 1945 to 1990.”)

Von Braun was not only a rocket scientist he was also an anti-communist propagandist who worked closely with Walt Disney. (Disney made a film about him and his background was purposefully forged: this former Nazi SS officer who worked under Heinrich Himmler, was made into an anti-Nazi dissident. The truth would have been too embarrassing). Disney and von Braun helped to mold public opinion, and the latter had a key role in putting pressure on the government to keep funding the program. U.S. newspapers such as The New York Times made the space program into a national matter of survival, as Douglas Brinkley covers in his book “Moonshot.” Von Braun also helped to make the moon landing into an essential element of defeating communism.

Military Moon Base

But U.S. plans for the moon were far more sinister. Project Horizon of 1959 centered on the feasibility of constructing a military base on the moon. And there were even discussions about whether the country that reached the moon first had the right to own it (very much like the race between colonial powers). The U.S. seriously talked about taking the military confrontation between the two superpowers into outer space. It was argued that causing destruction in space would have been better than battling it out here on Earth.

President John F. Kennedy and Wernher von Braun in 1962. (Marshall Space Flight Center/NASA)

One analyst in Business Week explained the economic and political benefit of the moon project: “… a means of giving employment to our scientists and engineers and, at the same time, of giving entertainment to the masses, just as the Middle Ages invented the tournament to give employment to warlike knights” (Leonard Silk, “John Q. Public and the Space Age,” p. 64 of “Reflections on Space: Its Implications for Domestic and International Affairs.”). There was also a plan by the Air Force in New Mexico to detonate an atomic bomb on the moon to study the effects of moonquakes.

The propaganda thrust of the program was clear from the beginning. Government documents expressed alarm, even in Western Europe, about the rising “prestige” of the U.S.S.R. due to its space accomplishments. Many meetings were held over how to boost U.S. prestige through the space program. The PR was as important as the science; “medical standards” for excluding crews included such factors as “extreme ugliness” or “any deformity which is markedly repulsive” (see the second chapter of “Shoot for the Moon,” by James Donovan). The Soviet program was more scientific, and that also made the U.S. propaganda task easier.

Neil Armstrong was less jingoistic about his trip to the moon: and the mission insignia of Apollo 11 (designed by the crew) significantly excluded an American flag (unlike patches of other missions) but the bald eagle sent a patriot message. The planting of the U.S. flag was NASA’s order (there were talks of planting a UN flag — there are now six U.S. flags on the moon, but their colors have been faded by sunshine). Armstrong did not invoke God (unlike Apollo 8 when members of the mission read from Genesis). But Armstrong was a deist and he watched in silence as Buzz Aldrin performed communion before stepping on the moon.

Neil Armstrong was less jingoistic about his trip to the moon: and the mission insignia of Apollo 11 (designed by the crew) significantly excluded an American flag (unlike patches of other missions) but the bald eagle sent a patriot message. The planting of the U.S. flag was NASA’s order (there were talks of planting a UN flag — there are now six U.S. flags on the moon, but their colors have been faded by sunshine). Armstrong did not invoke God (unlike Apollo 8 when members of the mission read from Genesis). But Armstrong was a deist and he watched in silence as Buzz Aldrin performed communion before stepping on the moon.

As soon as the U.S. beat the Soviets, interest in moon landings faded and space exploration is no longer a national priority. The scientific aspects of the space missions were highly exaggerated (just as the military and intelligence purposes were classified). And the moon, since human feet have stepped upon it, has become less romantic and seems to have inspired less poetry.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive language toward other commenters or our writers will be removed.

Thanks for this piece of revisionsist tripe. The battle for space was a battle between the our German rocket scientists and their German rocket scientists. The fact that their leader happened to be Russian simply hid the fact that they maintaind a little colony of German roscket scientists that they had managed to kidnap from Germany.

This attempt at glorifying the greatest catastrophe of the last century, the soviet union and all its usefull idiots throughoout the world is simply unbelievable.

I abhor people who maintain an admiration for Communism in all its forms and pity all the shitty little countries they manage to dupe into following in its disastrous path. You are worse than the neo Fascists, with a buther’s bill that far exceeds anything Hitler ever did.

Mostly BS. I like how you refer to ‘the theft of the design’ link to article that if you read it says, “Did it make a difference to the outcome of the Space Race? Probably not.” Even it they did steal something from the Soviets it pails in comparison to the what the Soviets stole from the US in WW2 (ie. A-Bomb and B29 designs and technology).

But I suppose the part you prefer then is the one referring to Wernher von Braun and Operation Paperclip…

Most serious US rocket scientists declared, in public, that without the inventor of the Nazi rocket bomb V2 (on which design the first NASA rockets were based; the V2 killed about 9,000 people, in cities like London, Antwerp, mostly civilians, during WW2, while it killed about 12,000 workers used as slaves on the V2 construction sites in Germany… Well worth a death sentence in Nuremberg at the time.) the US would have taken many more years to get to their objective of landing on the moon.

While, in private, the same US rocket scientists acknowledge that, without the Nazi scientist contribution, they would NEVER have succeeded.

The ultimate irony is that von Braun’s researches that led him to conceive the V2 were based on the ground-breaking works in ballistics … by a Russian scientist, of whom a copy of his theories were found covered with annotations by young von Braun’s hand.

Happy Birthday, US Military-Industrial Complex in Space!! Ugh!!

I just want to point out that the Russians have been maintaining the space station as a global resource since the U.S. more or less lost interest in the space program.

Also, It seems like NASA lost its support base NASA while private companies originally restrained from experimenting with space technology were to eventually become the keepers of the dream. Weapons manufacturers could buy up satellite manufacturers and form a basis for weapons in space, I suppose. But that isn’t the same as scientific exploration.

If they really work at it, they will create a shield around the earth which will prevent real space travel for a very long time.

How ironic it is that Disney would create anti-Nazi propaganda cartoons during WWII, and then try to rehabilitate one such Nazi after the end of WWII. Did you know they support abortion too?

Thank you for the article. I am from USSR. I know what space exploration had meant to us back then

Von Braun was a war criminal, he had used slave labor while working for Hitler.

Now USA rulers use Russian (Soviet) rockets to bring USA astronauts to the space station, by the way.

We have another space race in the offing with more nations: Japan, China, India, etc with more to follow in my opinion. and the race is on for a sustainable moon colony based on geological evidence of the abundance of water. The US may reconsider it’s manned mars mission in light of such information. And there is also the issue of the militarization of space with missile platforms, Laser platforms etc. Science fiction is starting to come true. Then there is the environmental change which could redirect all of our energies in a race for survival .

Sorry that I missed the point in part of the headline: The Angry Arab etc. Exactly why is the Arab angry?

‘The Angry Arab’ was Prof. As’ad AbuKhalil’s now defunct blog, great to have him here at CN. Plenty of his articles on this site that will probably make you ‘angry’ too.

The US Mars mission is now off, or 20 years away as it has been since the mid ’60s. The plan under Trump is to return to the Moon by 2024 with the Artemis program before it gets defiled by any ‘Sh*thole Countries” (India just launched a Lander last week). He has refused to fund the large ‘Exploration Upper Stage’ for NASAs SLS rocket, which would have allowed it to launch to Mars or carry cargo along with the Orion crewed spacecraft.

Instead he wants to build a small space station around the Moon, with the cargo sent by private space companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX. That way the US gets an overpriced and underpowered SLS, plus fat cargo contracts for the private space companies. A reusable Moon lander will shuttle between the Lunar Station and the Moon. Russia is very keen to participate, but in the current climate of craziness this seems unlikely.

China and Russia are both working on Saturn V class rockets, the Long March 9 and the Yenisei. But sanctions and an engine failure on the smaller Long March 5 (set to launch a mission to return samples from the Moon this year) have slowed progress. I hope they make it to the Moon & Mars before Trump & Elon Musk, I share AnneR’s trepidation about Capitalism spreading to other planets!

(Apologies if this is off-topic or irrelevant:)

In almost every debate I’ve come across discussing whether America should go metric, at least one commentator will say something about there being two different types of countries: one that uses metric/Celsius, and one that has landed man on the Moon. Some interpret this as American exceptionalism writ large, as if America is “too good” for metrication.

While much of the US moon mission was indeed done in customary units, von Braun designed the rocket in metric behind-the-scenes, which were then converted to customary. And even with that, it wouldn’t make much of a difference if it were done in metric. It does not show the superiority of either system any more than the widespread use of Macs in movies and TV shows makes Macs better than Windows PCs. It’s yet another excuse to justify American “superiority”, if not “exceptionalism”; the USSR’s use of metric certainly didn’t prevent them from launching the first man in space.

If China’s and/or Russia’s mission were to succeed, then hopefully it would put this long-standing dichotomy to rest.

Thank you Professor AbuKhalil for voicing my own views and perceptions so succinctly.

Frankly the weeks long “celebration” of this supposedly momentous occasion (of the first moon landing by humans) has bored the heck out of me. And its jingoistic, Orwellian nature has nauseated.

Neither on NPR, PBS nor the BBC World Service during all of the hours devoted to it – except for one brief time and that by an outside scientist/knowledgeable person on the latter – has there been *any* mention of the background to this moon venture. Not a single nod, even, in the USSR’s direction, not a whisper about Gargarin, Tereshkova, the little dog (which died in outer space), or about a space craft (no one on it) landing on the moon – *all* before the USA got their (stolen) act together. And of course, not a single mention of the fact that NASA’s Apollo program was a) led by von Braun nor b) that the US had stolen at least some of the USSR’s data on how to accomplish a space-worthy vehicle.

Indeed one person on the World Service even said that until the Americans (bien sur) no human had gone beyond the earth’s atmosphere.

We humans should be spending our time, money and mental efforts in cleaning up our own destructiveness here on this wonderful planet, not burning up billions on space ventures (with the prospect of f***ing up another planet).

Thanks for giving credit where credit is due to the Soviet space program. When I was an awkward kid in the ’80s who dreamed of space, I wanted to be a Cosmonaut, not an Astronaut. US astronauts seemed to be mostly square jawed, aggressive military types. Soviet cosmonauts on the other hand, looked like a bunch of slightly overweight science nuts like me.

I wanted to get my planetary science degree and emigrate to the Soviet Union, then train at Star City outside Moscow to ride their magnificent new Energia rocket. The Energia could carry a clone of the US space shuttle attached to its side, as the Brezhnev era military brass insisted on a vehicle with equivalent capabilities. They knew the hype about the US space shuttle radically reducing launch costs and flying once a week was BS, they thought the plan was to send it up with a payload bay full of X-ray lasers to cook the USSR’s ICBMs in their silos. But because the main engines were part of the Energia rocket, not the Buran shuttle, it could carry other heavy payloads (like space stations) to earth orbit. By adding an upper stage, it could send humans to the Moon and Mars. Nasa hopes to have this capability by 2020 with its much delayed SLS rocket, built from ’70s era Shuttle tech.

But with the end of the Soviet Union, Energia and its Buran Shuttle were left to rot, and the last flightworthy Energia and the only Buran to have flown in space were destroyed when their hanger collasped due to lack of maintenance. That was the end of my dreams of Space.

But it did pique my interest into human social systems. How did the Soviet Union achieve so much in Space, and at the same time provide a dignified life for its peoples? Why did the infinitely richer US lag behind in the early “space race” and abandon its ability to send humans beyond Earth orbit, while many of its citizens continue to go without the basics?

In his Memoir “Rockets and People”, Soviet Space designer Boris Chertok, whose experiences stretched from the crowds of the 1917 Revolution and Lenin’s funeral in 1924 to the assembly of the International Space Station in the 21st century, makes it clear that the experiences of his generation in building and defending a Socialist society were key to these achievements:

“I am part of the generation that suffered irredeemable losses, to whose lot in 20th century fell the most arduous of tests. From childhood, a sense of duty was inculcated in this generation – a duty to the people, to the Motherland, to our parents, to future generations, and even to all humanity.

…

Currently … it is ideological collapse that threatens the objective recounting of [Soviet] science and technology … motivated by the fact that its origins date back to the Stalin epoch or to the period of the ‘Brezhnev Stagnation'”

US accounts of the Soviet Space program always make snarky comments along the lines of “wow look what these primitives achieved in their Totalitarian, antisemitic hellhole.” No one likes to acknowledge that most of the US Moon program took place in the Jim Crow South under the command of Nazi war criminals. The designer of the Saturn 5 Moon rocket, Arthur Rudolph, was in charge of production of the V2 missile at the ‘Mittlewerk’ factory using slave labour from the Dora concentration camp. He had to be deported in 1984 when this became embarrassing.

In his book “Moon Lander” Grumman designer Thomas J. Kelly recounted his difficulties finding accomodation in Cape Canaveral for his engineers working in the Lunar Lander. The problem? Grumman was based in Bethpage NY and many of its engineers were Black. No hotel in Jim Crow Florida would take them! While the Jewish Chertok rose to the highest levels of the Soviet program in the ‘antisemitic hellhole’ of the USSR. You can download his memoirs for free here:

https://www.nasa.gov/connect/ebooks/rockets_people_vol1_detail.html

Thank you for the article

Why the iPhone 2019-20 is doomed: how would the iPhone 11 look: Analyst Min-Chi Kuo, predicted that all three models of the 2020 model iPhone will have support for 5G

Why the iPhone 2019-20 is doomed: how would the iPhone 11 look

Analyst Min-Chi Kuo, known for his accurate predictions for Apple, predicted that all three models of the 2020 model iPhone will have support for 5G. On the one hand, this is certainly an excellent marketing factor for next year’s Apple gadgets, but on the other, another nail in the coffin lid of models that will be released in 2019.

This is BS cubed. US went to the moon because it could. All the Cold War stuff was merely a sales pitch for the rubes (like this author) who are absolutely incapable of understand folks who are motivated by difficult projects. “We CHOOSE to go to the moon and do those other things, not because they are easy, but because they are HARD.” JFK—who really did understand. “I, for one, do not want to go to sleep by the light of a Soviet moon.” LBJ—king of the rubes. This was an expensive project and LBJ could pass large appropriations bills. Let him claim the “high ground” of space as long as he kept the project funded.

The MOST important factor in the success of Apollo, by FAR, was the army of young engineers who came through the programs of the public universities of the USA Midwest. Neil Armstrong wasn’t the only important aero engineer from Purdue. And it wasn’t just the giants like Michigan that contributed, arguably the best ground controller was a guy named John Aaron who was a physics grad from Southwest Oklahoma State. Werner von Braun did a splendid job but his team was only 1500 out of 400,000. Most of the rest were small-town kids and farmboys who grew up understanding what it takes to make hideously complex and difficult projects succeed. Their task was to build something that no one had built before, and make it work in front of 600,000,000 onlookers—most of whom had NO idea what was being accomplished.

In 1965, our family was visiting my father’s kin in Kansas. His cousin worked as a machinist for Boeing in Wichita and space-buff me got into an excited conversation with him about the space race. Boeing was tasked with building the first stage of Saturn V—lots of cool stuff to talk about. After awhile, his father piped up, “You two think the space race is a big accomplishment. It is not. It’s a stunt. If you really want to talk about this country doing difficult and important things, then we should be talking about the Panama Canal. We built that marvel after the French builders of the Suez Canal GAVE UP.”

Hard to remember that USA was once a country that could go to the moon as a mere manifestation of The Instinct of Workmanship. Personally, I would like to see that country come back—mostly because those instincts would come in very handy if we are ever to build the sustainable society.

jonathan larson is at least started with admitting that his comment was BS.

In order for my account to be wrong, I would have to ignore the efforts of over 400,000 dedicated, hard-working, virtuous people. But pay to attention to me. Here is Neil Armstrong’s account of why the moon landing was successful.

As’ad listed a lot of facts to prove his article. NA’s words are NOT a refutation of the article.

As I very quickly approach three score years and ten, my disillusionment with my own country is becoming unbearable. I believed the ideals and principles of my country that I was taught in school in the ’50s. My first disillusionment was Vietnam. It’s gone downhill from there. Does no one stand on principles and ideals? Did they ever? This may come as a surprise to some Americans but some other countries do stand on principles and ideals. Little Costa Rica, who has no military, did that while I was there on vacation. They arrested some muckety muck politician who had committed a crime in CR some years earlier and was now returning, got arrested when he arrived. They were quite proud of themselves.

Could there be the same kind of rot at the core of that arrest that you see in so many US efforts – like Vietnam, like the space program, like telling Bolsonaro not to refuel the cargo ships taking food to Iran, like the economic warfare we’re waging on Iran? Sure. But the buzz was on the street. People in the street were talking about it and taking pride in the thought that they were trying to follow the rules, as it were. We’re a democracy they were saying. It’s funny because Thump has spoken of “draining the swamp” and, right enough, Washington, DC was a swamp. But the end of the 14th street bridge is (or, at least, was) called the foggy bottom. That’s where all the deals got done.

I ‘spect that we got the government we deserved.

I don’t understand why Mr. Abu Khalil has such a rank attitude about America, but why don’t you just come out and say it: I hate America. I hate Americans. So what if America can’t remember Russian cosmonauts, geeze. The world is infinite shades of grey, Mr. Abu Khalil. You being from Lebanon should know that very well.

US Americans are ignorant and they seem to be proud of it, judging from your comment. They have this arrogant attitude that they don’t need to learn anything about other countries, because anything that is not from the United States is not worth of their attention. They don’t even know where Syria is.

jsinton, don’t be so sensitive ! Most people mistakenly take criticism of USA personally. America and Americans are not even vaguely one and the same thing.

Why jsinton is so full of ignorance (imperialist propaganda)?

Not another ‘if you don’t like it, go away’ moan. See the faults of your own people please. The USSR was (and Russia still is!!) far ahead of the USA in scientific ideas, education of students in science and also many other military matters (see Andrei Martyanov’s book “Losing Military Supremacy”) for details. Spending money and beating drums for war is not proof of intelligence/brains and useful achievement.

Nice little article but get ready for 99 comments about the moon landing being a dirty dirty hoax.