This story of seeming failure is surprisingly hopeful for the future of labor, writes Steven C. Beda.

(Museum of History & Industry, CC BY)

By Steven C. Beda, University of Oregon

The Conversation

It shut down a major U.S. city, inspired a rock opera, led to decades of labor unrest and provoked fears Russian Bolsheviks were trying to overthrow American capitalism. It was the Seattle General Strike of 1919, which began on Feb. 6 and lasted just five days.

By many measures, the strike was a failure. It didn’t achieve the higher wages that the 35,000 shipyard workers who first walked off their jobs sought – even after 25,000 other union members joined the strike in solidarity. Altogether, striking workers represented about half of the workforce and almost a fifth of Seattle’s 315,000 residents.

Usually, as a historian of the American labor movement, I have the unfortunate job of telling difficult stories about the decline of unions. However, in my view, the story of this particular strike is surprisingly hopeful for the future of labor.

And I believe it holds lessons for today’s labor activists – whether they’re striking teachers in West Virginia or Arizona, mental health workers in California or Google activists in offices across the world.

Low Wages, Soaring Living Costs

The Seattle General Strike had its origins in the city’s many shipyards.

During World War I, workers flocked to Seattle to take jobs as welders, pipefitters, riveters and other dozens of jobs in the early-20th century shipyard. In 1918, there were about 16,000 shipyard workers in Seattle. Just a year later, their numbers had swelled to 35,000.

While work in the shipyards was plentiful, it wasn’t exactly lucrative. Throughout World War I, workers continually demanded wage increases, and employers routinely ignored them. As rents and the cost of living climbed, the workers finally announced that, absent higher wages, they were going on strike on Feb. 6.

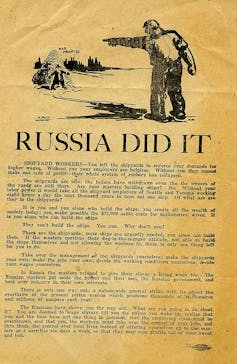

(Tothebarricades.tk, CC BY)

A few days before the deadline, the shipyard unions made a then-unprecedented request: They asked the Seattle Central Labor Council – which oversaw most of the city’s unions – to issue orders for a general strike, which brought out 25,000 cooks, waitresses, factory workers, store clerks and many others to join the 35,000 shipyard workers already striking.

Despite the usual divisions within unions along lines of race, gender, skill and citizenship, the majority of the locals belonging to the council voted to join the strike.

‘No One Knows Where’

Perhaps it was the rising cost of living that motivated workers across the city to walk off their jobs. Maybe it was a new culture of working-class solidarity emerging in post-World War I America.

Most certainly, it had much to do with the words of Anna Louise Strong.

A pacifist, feminist and welfare advocate, Strong made a name for herself reporting for Seattle’s Union Record, the major union newspaper in the city.

An editorial she authored on Nov. 4 encouraged Seattle’s workers to put aside their differences and embrace a new future in which all workers were united. Her editorial ended with what would become iconic lines in American labor history: “We are starting on a road that leads – NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!”

Strong’s point was to promote unity among Seattle’s workers, not advocate revolution, though that’s not how many politicians interpreted it. The Russian Revolution two years earlier still weighed on the minds of the city’s elite and many worried that Strong’s editorial was the opening salvo in a war to overthrow American capitalism.

(The Town Crier Newspaper, CC BY)

The Violence That Never Came

Fearing violence, anti-labor organizations and the city’s politicians peppered the streets with pamphlets warning that Bolsheviks were behind the strike. Newspapers as far away as New York picked up Strong’s editorial and ran sensational stories of the strike that stoked alarm over a rising tide of radicalism.

While Seattle did lurch to a halt, the violence that Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson and others feared never came. Hanson called on the police force to maintain order in the city, through violence if necessary, and asked the governor to mobilize the National Guard. He even paid students from the University of Washington to patrol the streets.

But in the words of Earl George, a striking dockworker who went on to became the first African-American president of Seattle’s longshoremen’s union, “Nothing moved but the tide.”

What George and workers remembered as they walked away from their jobs was the peacefulness of the city. And with shops and restaurants closed due to the strike, the workers themselves pitched in to provide essential services, such as stocking food banks and washing sheets at hospitals.

(AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

The Power of Solidarity

What ultimately ended the strike, on Feb. 11, was the very thing Strong warned against in her editorial: divisions among workers.

Unions representing skilled workers began to fear that the general strike was undermining their prestige and began ordering members back to work. Other unions succumbed to the threats being made by Hanson and returned to their jobs.

In purely material terms, the strike was a failure. It also directly contributed to a new wave of repression and the “red scare” of the post-World War I era.

Yet, the strike was not without meaning. It’d proven to workers, both in Seattle and elsewhere, that there was power in unity, however fleeting. For five days, workers had shut down the city and then run it themselves.

For today’s workers tired of decades of wage stagnation and fleeting benefits in the gig economy, the Seattle General Strike offers an important lesson about the power of organized laborers: When united, workers can take on the most powerful foes.

Striking teachers, activists at Google and participants in the Women’s March, to name just a few examples, are today standing on the same road that Anna Louise Strong described 100 years ago.![]()

Steven C. Beda is assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thanks for mentioning the important role Anna Louise Strong played through her writing with the Union Record.

An excellent resource for further reading on avoiding the need to strike in a Capitalist economy, with Socialism / Marxist economic theory is available from Professor Richard Wolff rdwolff.com

His work shows how these theories were put into practice in the early 19th C and followed 2 primary paths. Communists, as in the USSR, and how it regressed into horrible govt tyranny and strikes could lead to prison/death; and Democratic Socialists, as in some Nordic nations, which still allowed capitalists / markets, but with Socialist regulations, but which unfortunately were not enough to prevent the capitalists from upsetting the system.

The lessons learned from Prof Wolff is that the economic framework must begin with worker controlled co-ops, to prevent govt or capitalist control.

Conditions are profoundly different today. By the 1980s, it was middle class workers that went all-out against unions, calling them “leftist organizations,” etc. Today, only some 11% of US workers still belong to unions. And liberals today seem numbly unaware of how deeply we’ve been split apart, pitted against each other over the past 20-some years — middle class vs. poor, workers vs. those who have been left jobless.

Interesting. I’m originally from Seattle but was not aware of this. My grandfather, Henry Stanley was instrumental in the early labor movement in Butte, Montana/Anaconda copper mine. The early labor movement was closely associated with the communist movement, until Labor distanced itself when folks realized what was actually going on in the Soviet Union. But my grandfather, idealist that he was, held a communist party card until 1998.

In 1919 wages were low, particularly for unskilled labor. How low? Well, how many loaves of bread could a worker buy with one days wage? Not many. Today, due to inevitable human nature, the unions can be at times corrupt, or at least self serving, and have insisted on wages beyond what the natural market will support. Ironically, my grandfather, carpenter house builder, and always a union supporter was cheated out of his pension by the very organization he supported all of those years.

Using carpenters as an example, in the USA, residential carpenters and union carpenters are two different animals. Their skill sets differ.

Union carpenters work mostly on commercial jobs in urban areas—office buildings, rebar, concrete. Their wages are stable, and so high one cannot afford to have them build a residential house. They receive typical benefits, pensions etc.

Residential carpenters typically work fast and hard, at much lower wage, with zero benefits or pensions. Why? Because that is what the market will bear. When there’s a building boom wages rise, during a slump wages decrease. Due to that, residential carpenter wages are a reasonable litmus test as to the health of the economy.

Today, it is likely the best time in all of the history of mankind to be a government worker, especially federal or state. Please correct me if I am wrong on this, but I read that over 22% of federal employees receive six-figure salaries + benefits. Today government workers in general get more than equivalent workers in the private sector. Teachers actually work hard for their salaries, but like the rest of them, when their salaries gradually allow them to buy fewer loaves of bread, they somehow think they should get standard of living increases.

Not so in the private sector. The private sector more competes in the international market. How many widgets can you build and market compared to widgets made and marketed by a foreign company? If you can’t compete, you go out of business. (Detroit) The auto workers unions pushed wages so high the companies cannot afford to build cars there.

The typical psychology of the worker mentality does not understand what I takes to dream up, start up, run and maintain a business. Dynamic, smart people can gain wealth in the USA. Worker psychology resentment of the business sector is rooted in envy, and yet the majority of workers have no interest or drive to have those dreams or take those risks. In the private sector, workers rely on the “man” to write their checks, but resent them because they have a better life style.

Communism, and it’s slightly cuter younger sister Socialism are both recipes for mediocrity in a society. Consider the old Soviet Union. Those poor people forgot how to do anything well.

A friend is from southern Germany, and had relatives in East Germany. I asked her what happened to all of those government people after the wall came down who were spying on every citizen . Incensed, she said, “They just went back to doing the same—working in government!”

There is no such thing as a “natural market”.

Steven C. Beda

Many Thanks Consortiumnews for selecting this timely piece. It’s enspiring to see young, accomplished teachers aspiring to get the stories of American Labor back in front of the reading public. Thanks too to Professor Beda.

“Workers Of The World, Unite,” probably as much as a truism as can be said. Locally we have a Suprmarket Chain founded by an owner that Also believed that, and though he fought mightily with them over each contract, he deeply appreciated “his” workers. That is the kind of work environment we need to bring back our workforce.

My best mentor over the years, who was a member of Patton’s Third Army, built one of our very best local construction companies around the concept of Union Trade Skills and stood by “his” workers through good and hard times. My point is, that it it will become more important through time that we regain this Lost History.

The mistake of this generation was in forgetting that the labor movements of the past were driven by the masses — poor and middle class, workers and their “brothers and sisters” who got phased out of the job market. That defines the deep split in today’s generation. Because only some 11% of US workers are in unions, and those unions have effectively been neutered and declawed, they are no longer particularly relevant.