The U.S. has long had a love-hate relationship with international norms, having taken the lead in forging landmark human rights agreements while brushing off complaints over its own abuses, Nat Parry explains.

By Nat Parry

American exceptionalism – the notion that the United States is unique among nations due to its traditions of democracy and liberty – has always been the foundation of the nation’s claim to moral leadership. As a country founded on ideals that are today are recognized the world over as fundamental principles of international norms, the U.S. utilizes its image as a human rights champion to rally nations to its cause and assert its hegemony around the world.

Regardless of political persuasion, Americans proudly cite the influence that the founding principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights have had on the rest of the world, with 80 percent agreeing that “the United States’ history and its Constitution … makes it the greatest country in the world” in a 2010 Gallup poll. Respecting these principles on the international level has long been considered a requisite for U.S. credibility and leadership on the global stage.

Regardless of political persuasion, Americans proudly cite the influence that the founding principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights have had on the rest of the world, with 80 percent agreeing that “the United States’ history and its Constitution … makes it the greatest country in the world” in a 2010 Gallup poll. Respecting these principles on the international level has long been considered a requisite for U.S. credibility and leadership on the global stage.

Much of this sentiment is an enduring testament to U.S. leadership following World War II, a period in which international legal principles of human rights and non-aggression were established, as well as the four decades of the Cold War, in which the “free world,” led by the United States, faced off against “totalitarian communism,” led by the Soviet Union.

During those years of open hostility between East and West, the U.S. could point not only to its founding documents as proof of its commitment to universal principles of freedom and individual dignity, but also to the central role it played in shaping the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Fourteen Points and Four Freedoms

While the U.S. didn’t fully assume its position as moral arbiter until after the Allied victory in World War II, its role in these matters had already been well-established with Woodrow Wilson’s professed internationalism. As expressed in his famous “Fourteen Points,” which sought to establish a rationale for U.S. intervention in the First World War, the United States would press to establish an international system based on “open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.”

British Vickers machine gun crew wearing PH-type anti-gas helmets during the Battle of the Somme in WWI.

Wilson had seen the First World War as evidence that the old international system established by the Europeans had failed to provide necessary security and stability, and sought to replace the old diplomacy with one based on cooperation, communication, liberalism and democracy.

Speaking on this issue throughout his presidency, he consistently advocated human rights and principles of self-determination.

“Do you never stop to reflect just what it is that America stands for?” Wilson asked in 1916. “If she stands for one thing more than another, it is for the sovereignty of self-governing peoples, and her example, her assistance, her encouragement, has thrilled two continents in this Western World with all the fine impulses which have built up human liberty on both sides of the water.”

These principles were expanded upon by subsequent American administrations, and especially by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In his January 1941 State of the Union address, Roosevelt spelled out what he called “the Four Freedoms,” which later became the foundation for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“In the future days,” he said, “which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.”

He continued: “The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want – which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants – everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear – which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor – anywhere in the world.”

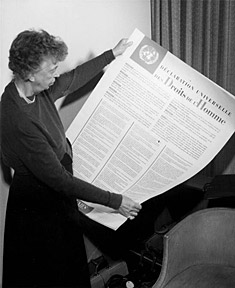

Following the Allied victory over the Axis powers, FDR’s widow Eleanor Roosevelt took her late husband’s vision and attempted to make it a reality for the world through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Chairing the Commission on Human Rights, a standing body of the United Nations constituted to undertake the work of preparing what was originally conceived as an International Bill of Rights, Eleanor Roosevelt pushed to ensure that FDR’s “four freedoms” were reflected in the document.

Under Roosevelt’s leadership, the Commission decided that the declaration should be a brief and inspirational document accessible by common people, and envisioned it to serve as the foundation for the remainder of an international bill of human rights. It thus avoided the more difficult problems that had to be addressed when the binding treaty came up for consideration, namely what role the state should have in enforcing rights within its territory, and whether the mode of enforcing civil and political rights should be different from that for economic and social rights.

As stated in its preamble, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.”

Much of the language in the Declaration echoed language contained in the founding documents of the United States, including the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. Whereas the U.S. Declaration of Independence articulates the “unalienable right” to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.”

While the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits Congress from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,” the UDHR provides that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression” and that “everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.” Whereas the Eighth Amendment forbids “cruel and unusual punishments,” the UDHR bars “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Although the United States made it clear that it could not support a legally binding UDHR, it readily endorsed the final document as a political declaration, one of 48 nations to vote in favor of the Declaration at the UN General Assembly in December 1948. With no votes in opposition and just eight abstentions – mostly from Eastern Bloc countries including the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Poland – the Declaration served as a defining characteristic of the contrast between East and West in those early days of the Cold War.

A Small Problem

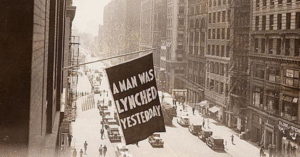

There was of course one small problem. Despite the United States formally embracing “universal human rights” on the international stage, its respect for those rights domestically was considerably lacking. Throughout the country and especially in the South, African Americans endured racist segregation policies and were routinely denied the right to vote and other civil rights.

Lynching, while not as pervasive as its heyday earlier in the century, was still a major problem, with dozens of blacks murdered with impunity by white lynch mobs throughout the 1940s.

In 1947, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed an “Appeal to the World” petition in the United Nations that denounced racial discrimination in the United States as “not only indefensible but barbaric.” The American failure to respect human rights at home had international implications, argued the NAACP. “The disenfranchisement of the American Negro makes the functioning of all democracy in the nation difficult; and as democracy fails to function in the leading democracy in the world, it fails the world,” read the NAACP petition.

The NAACP’s appeal provoked an international sensation, with the organization flooded with requests for copies of the document from the governments of the Soviet Union, Great Britain and the Union of South Africa, among others. According to NAACP chief Walter White, “It was manifest that they were pleased to have documentary proof that the United States did not practice what it preached about freedom and democracy.”

The U.S. delegation to the UN refused to introduce the NAACP petition to the United Nations, fearing that it would cause further international embarrassment. The Soviet Union, however, recommended that the NAACP’s claims be investigated. The Commission on Human Rights rejected that proposal on December 4, 1947, and no further official action was taken.

According to W.E.B. DuBois, the principle author of the petition, the United States “refused willingly to allow any other nation to bring this matter up.” If it had been introduced to the General Assembly, Eleanor Roosevelt would have “probably resign[ed] from the United Nations delegation,” said DuBois. This was despite the fact that she was a member of the NAACP board of directors. While Roosevelt’s commitment to racial justice may have been strong, it was clear that her embarrassment over the U.S.’s failures to respect the “four freedoms” at home was even stronger.

It was in this context that the United States endorsed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. That year also marked the beginning of tentative steps the U.S. began making towards respecting basic rights within its borders.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which ended segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces. The next month, the Democratic Party included a civil rights plank in its platform. “The Democratic Party,” read the platform adopted at the 1948 Democratic National Convention, “commits itself to continuing its efforts to eradicate all racial, religious and economic discrimination.”

While there was clearly a domestic motivation for embracing the cause of civil rights (presidential adviser Clark Clifford had presented a lengthy memorandum to President Truman in 1947 which argued that the African-American vote was paramount for winning the 1948 election), there was also a strong international component to the Democratic Party’s support for civil rights.

UN Bragging Rights

In addition to its civil rights plank, the 1948 Democratic platform included a wholehearted endorsement of the recently established United Nations, and expressed “the conviction that the destiny of the United States is to provide leadership in the world toward a realization of the Four Freedoms.” But the Democrats recognized that the U.S. had a long way to go to realizing those four freedoms at home.

“We call upon the Congress to support our President in guaranteeing these basic and fundamental American Principles: (1) the right of full and equal political participation; (2) the right to equal opportunity of employment; (3) the right of security of person; (4) and the right of equal treatment in the service and defense of our nation,” the platform stated.

The Democratic platform also proudly pointed to the accomplishment of organizing the United Nations: “Under the leadership of a Democratic President and his Secretary of State, the United Nations was organized at San Francisco. The charter was ratified by an overwhelming vote of the Senate. We support the United Nations fully and we pledge our whole-hearted aid toward its growth and development.”

For its part, the Republican Party also embraced the fledgling UN, stating in its 1948 platform that “Our foreign policy is dedicated to preserving a free America in a free world of free men. This calls for strengthening the United Nations and primary recognition of America’s self-interest in the liberty of other peoples.” While the Democrats pointed to the president’s leadership for helping establish the UN, the Republicans also wanted to make sure that they received due credit. Their party platform listed “a fostered United Nations” as one of the main accomplishments of the Republican Congress, despite “frequent obstruction from the Executive Branch.”

As “the world’s best hope” for “collective security against aggression and in behalf of justice and freedom,” the Republicans pledged to “support the United Nations in this direction, striving to strengthen it and promote its effective evolution and use.” The UN “should progressively establish international law,” said the Republicans, “be freed of any veto in the peaceful settlement of international disputes, and be provided with the armed forces contemplated by the Charter.”

As a major component of the progressive establishment of international law, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was to be codified into legally binding treaties.

Although the Declaration was endorsed by the U.S. and 47 other countries in December 1948, the two corresponding legally binding covenants to define the obligations of each state required another two decades of work. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights were ready for ratification in 1966, some 18 years later.

The United States became a signatory to both covenants on Oct. 5, 1977. It ratified the ICCPR on June 8, 1992, but to this date has not fully subscribed to the ICESCR, one of just seven countries in the world not to ratify the agreement.

Cold War Context

Throughout those years, the U.S. was engaged in an intense ideological battle with the Soviet Union, in which human rights were used as a rhetorical weapon by each side against the other. While American leaders chastised the Soviets for their failures to respect fundamental liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of speech and freedom of association, the USSR could readily point to the blatant institutionalized racism that plagued American society.

Racial discrimination belied America’s rhetoric about democracy and equality, making the U.S. cause of freedom look like a sham especially to people of color in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The Soviets enthusiastically exploited the issue, imbuing their anti-capitalist propaganda with tales of horrors suffered by African Americans.

So, in 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Brown v. Topeka Board of Education that segregated schools were unconstitutional and ordered that school integration proceed “with all deliberate speed,” the case was trumpeted by the American establishment as evidence of the great strides being made toward full equality for all citizens.

At times, racial discrimination in the United States caused such international embarrassment that the State Department would pressure the White House to intervene. In 1957, for example, when a Federal District Court ordered the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, to allow African-American students to attend, Governor Orval Faubus declared that he would refuse to comply with the decree. Several hundred angry and belligerent whites confronted nine African-American students who attempted to enter the school on September 4, 1957.

National Guardsman prevents four black students from entering Little Rock Central High School; September 4, 1957.

The National Guard, called up by Faubus, blocked the students from entering the school. Pictures of the angry mob, the frightened African-American students, and armed National Guardsmen were seen all over the world, and the Soviets eagerly seized on the propaganda.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles informed President Dwight Eisenhower that the Little Rock incident was damaging the United States’ credibility abroad, and could cost the U.S. the support of other nations in the UN. Eisenhower attempted to negotiate a settlement with Faubus, but when that failed, he sent in federal troops. The nine African-American students were finally allowed to attend Central High under the armed protection of the United States military.

The developing international human rights project led to deep ideological divisions in the United States, with some conservatives, especially in the South, concerned that the national government would use international human rights law to promote national civil rights reforms. Arguing that the civil rights question was beyond the scope of Congress’s authority and concerned about the constitutional power of treaties, conservatives launched several attempts in the 1950s to amend the U.S. Constitution to limit the government’s ability to subscribe to treaties.

Those failed efforts to amend the Constitution were based on the premise that the federal government had no say in the matters of states and localities in regulating race relations, and that since Article VI of the Constitution provides treaties the status of “supreme law of the land,” the U.S. would find itself subjected to the whims of the international community on these matters.

Those fears would prove unfounded, since the U.S. didn’t formally subscribe to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights until 1977, long after most of the relevant domestic civil rights legislation had been adopted, but the right-wing opposition to U.S. submission to international norms had become thoroughly established as American conservative orthodoxy.

Nat Parry is co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush.

As always, with the US it’s “do as I say, not do as I do.”

Excoriating Iran for a supposed lack of democracy after overthrowing the democratically elected government of Iran and propping up the most repressive regimes on the planet, like Saudi Arabia.

Trumpeting human rights as a pretext for wars of aggression and regime change, while institutionalising torture in a global gulag of secret prisons and torture chambers.

If there were prizes for hypocrisy, the US would het the gold medal every time.

Thanks for reminding us that postwar history is the story of US government bureaucrats fighting tooth and nail to keep human rights out of our reach.

Like other commenters, in an otherwise good posting, I take issue with the soft euphemism ‘complicated’ in the title — that’s something I would expect to read in a MSM think-piece, ala the NYT, WaPo, etc where the author doesn’t want to offend the delicate sensibilities of his readers and hence the advertisers. Far closer would be a phrase like ‘hideously hypocritical’ since we’re not talking about a romantic relationship here, but a country that has fomemented so many wars, invasions and coups in foreign countries that numerous books and articles (including one by Nat Parry here in CN recently) have been written about the MILLIONS of deaths that were caused, most recently by the Iraq War, and then has the audacity to lecture other countries about ‘human rights’.

Martins: I was going to stay with him, but he died Thursday.

Crabbin: Goodness, that’s awkward.

Martins: Is that what you say to people after death? “Goodness, that’s awkward”?

( from the movie “The Third Man”)

The US of A’s “complicated” relationship with International Human Rights norms is not complicated at all—it is called expediency. Shame on you for blaming “America” for the crimes of the USA. In any case, we are the world’s greatest hypocrites (apartheid Israel a possible exception,) everyone else commits war crimes except the USA. This holds true even for horrific, atrocious crimes that would make the Nazis blush: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, the saturation bombing of Dresden and Tokyo, My Lai and the hundreds of other hamlets that were destroyed Nazi-style in Vietnam, Abu Ghraib, Bagram AFB, Obama and his targeted killings, the Invasion of Iraq and Mosul and Fallujah in particular, the use of depleted uranium, agent orange, white phosphorous, the genocide we perpetrated in Indonesia, Guatemala. Guantanamo is an unspeakable house of horrors that not even Dante could imagine. Keep in mind that the three largest bombs ever dropped on human beings have all been dropped by the USA (not America) and they have all been dropped on Asians. Exceptionalstan uber alles.

I do not comprehend why the author uses the word “complicated” in the title of the article; I think the US relationship with international human rights norms have been pretty straight forward. I will use Woodrow Wilson as an example. According to author Tom MCnamara, ” during President Wilson’s time in office, the United States would intervene in Latin America more often than at any other time in her history. In addition to the invasion of Haiti, the US would send troops to Mexico in 1914, the Dominican Republic in 1916, again to Mexico in 1916 ( the US would send troops to Mexico 9 more times before Wilson left office), Cuba in 1917, and finally Panama in 1918. Wilson would also maintain US armed forces in Nicaragua, using them to influence Nicaragua’s president and ensure the passage of a treaty that was favorable to the United States. He also invaded Russia, supporting the “White” or anti-Bolshevik side in Russia’s civil war. It is difficult to believe that these were the actions of a man moved by the lofty ideals of democracy and free choice, or by someone concerned with “the children … the next generation.”Albeit different presidents have occupied the white house, US foreign policy has been crystal clear when it comes to “international human rights norms.” My way or the highway, so to speak.

The article leaves out the important fact that ICCPR is not self-executing, because Congress made that a ratification condition. In addition, the AMerican Bar Association opposed the ICCPR because the treaty would require “anti-lynching” laws.

Finally, dictionaries in the US once had the Four Greedoms set out in their inner front covers. Few people can recite the Four Freedoms, let alone defend them, today.

There is no such thing like the “USA relationship with International Human Rights norms”, since the USA “make their own reality”!

Dear Padre: even though you use one single sentence in your post, you hit the nail in the head. US has demonstrated that when it comes to abiding by the laws, it simply violates them or concocts them to fit its needs. And to top it all off, it accuses others when certain law is violated.

A few people in power may have sincerely believed the America as beacon for democracy and human rights rhetoric but this notion was quickly turned onto a cover for American Empire (which is just a continuation of Europe’s global imperialist legacy). And, as the piece points out, the glaring contradiction between rhetoric and reality was always there.

Today we are to believe a nation which does not even enshrine basic health care for all citizens as a fundamental human right goes to war not for the usual reasons empires fight but because it seeks to bring liberty and democracy to the oppressed masses. Riiiight…and I have a bridge and a great little plot of land in the Everglades I am willing to sell you for a very reasonable price.

The moral : Whenever a powerful country starts talking about being exceptional or indispensable and gives itself the divine right to wage war on any other nation on earth…know that if it is not disabused of this dangerous notion by an active citizenry the world will suffer tremendously and many people will die violently because of it.

Unfortunately great ideals are also the best disguise for gangsters, and the US failure to regulate economic power after 1850 ensured oligarchy control of mass media and elections, with liberty and justice for gangsters.

In Plato’s dialog The Republic, the sophist Thrasymachus declares, “Justice is the interest of the stronger.” In other words, might makes right – words that could well be printed on our US currency, since they represent the operational viewpoint of America.

Dear Mike: It is hard to disagree with your post. That has been exactly the US position when it relates to foreign policy. This article reminds me of the evil witch in White snow fairy tale ” Mirror, mirror on the wall, tell me who is the biggest rogue off all?” well done Mike.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is certainly the proper template or framework from which to establish international “norms”. But within the U.S. and across the globe, such rights are much removed from reality and “America’s relationship” to bridging that gap is negative.

We boast about the First Amendment and political rights, but in reality freedom of expression is under attack and our political system is “bought”. We boast about our supposed Free Press, but that’s bought too–and the spectrum of issues, content, and opinion that gets wide play is confined and constrained to an extraordinary degree. Lights even get turned down on peace advocates at political conventions. “Groupthink” in America is the “norm”. We boast about due process–yet Guantanamo, extrajudicial drone killings abroad, and the legal undermining of habeus corpus at home is the reality. We boast about freedom of assembly, yet the OWS movement was met with efforts of dispersal and the spraying of mace. We have a history that includes COINTELPRO and now mass surveillance. Corporate culture and oligarchal control makes pursuit of economic justice in America a fading pipe dream with insecurity and wealth gaps widening by the day.

We reserve the “right” to “preemptive war”– which is just a fancy way of saying “what we say and do goes” and international law applies when and if we say it applies. The right of people to be “secure” is blasted to hell by bombs and missiles at horrific rates and the use of white phosphorus, cluster munitions, and depleted uranium is our “norm”.

I guess America’s relationship to human rights norms is complicated by the fact that human rights are so very often simply ignored.

Very well said Gregory. Joe

I second the motion. Well stated.

Yes Gregory,

Our ideology is much different then our actual implementation at home and abroad.

Tell Laos about US worries re: human rights…

Anyway

1) Declaration of Independence has never been law. It was a middle finger to England.

2) BOR has never meant anything. The rights had all been given away in Article 1 of the Constitution. The Anti-Federalists and states got rickrolled.

Look no further than profit/market share to uncover the daily dealings of the beast. The USA has been under that heavy handed control since the dollar became pegged to energy/oil. It’s not a complicated enterprise that controls the USA. No different from the inner city street gangs. All day long the sheep never realize the hook is in their nose……He said, she said, they said….this is the song the sheep follow.

Excellent essay by Nat Parry. The US has also refused to sign the Treaty of Rome accepting jurisdiction of the ICC International Criminal Court, and has even passed a law to militarily attack the Hague if any US military member is brought there for trial. It’s influence upon the UN is purely coercive, deceptive, and hypocritical.

Sam F-

Yes, yours is a very important appendage to Nat’s excellent history lesson.

I have nothing but contempt for the arrogant bigot Wilson. FDR was a better person, and a far better president, but he didn’t really care about Black Americans. At least not enough to stick his neck out for them. The man was generally a great politician though, and the Four Freedoms speech was an example of that.

h**ps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Four_Freedoms_1c_1943_issue_U.S._stamp.jpg

h**ps://arago.si.edu/media/000/027/629/27629_lg.jpg

I’d imagine we’ll see nothing like this again – our billionaire and neocon rulers are unlikely to permit such rubbish.

Rephrasing that, Eisenhower attempted to fold like a wet noodle if Faubus would allow him to do so without losing face. “Ike” was coasting at this stage of his life. “Been there, done that”, and he didn’t want any excitement. Besides, he was in all essentials a genteel racist himself in the sense that he cared even less than Roosevelt for Black Americans. But Faubus forced his hand, and he had to do something.

Interesting and informative essay.