On January 31, 1968, Viet Cong forces attacked the U.S. Embassy in Saigon as part of the Tet Offensive, a turning point in the Vietnam War. On the eve of the 50th anniversary, veteran war correspondent Don North takes us back to that momentous event.

By Don North

It was the eve of battle. Ngo Van Giang, known as Captain Ba Den to the Viet Cong troops he led, had spent weeks smuggling arms and ammunition into Saigon under boxes of tomatoes. Ba Den was about to lead 15 sappers, a section of the J-9 Special Action Unit, against an unknown target. Only eight of the unit were actually trained experts in explosives. The other seven were clerks and cooks who signed up for the dangerous mission mainly to escape the rigors of life in their jungle camp near Dau Tieng, 30 miles northwest of Saigon.

On the morning of January 30, 1968, Ba Den secretly met with U.S. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker’s chauffeur, Nguyen Van De, an embassy driver who was in fact an agent for the Viet Cong. De drove Ba Den in circles around the Embassy compound in an American station wagon. De revealed that Ba Den’s mission was to attack the heavily fortified Embassy. Learning the identity of his target, Ba Den was overwhelmed by the realization that he would probably not survive the attack. Pondering his likely death, and since it was the eve of Tet, Ba Den wandered into the Saigon market, had a few Ba Muoi Ba beers and bought a string of firecrackers to light as he had done for every Tet celebration since he was a child.

Ba Den and his team were about to play a small but critical role in what we now call the Tet Offensive, the coordinated attack by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops against dozens of cities, towns and military bases across South Vietnam. When the bloody fighting ended after 24 days, the Communist troops had been driven from every target and the U.S. declared a military victory. However, the attackers scored a significant political and psychological victory by demonstrating an ability to launch devastating and coordinated attacks seemingly everywhere at once, and by showing that a U.S.-South Vietnamese victory was nowhere in sight. The attack on the U.S. Embassy was a potent symbol of that success.

I’ve thought a good deal about that attack on the Embassy over the last 50 years. I was there as a television journalist – lying in the gutter outside the Embassy as automatic fire buzzed above my head. Here is what I knew then and what I know now.

Later that night of January 30, Ba Den joined the other members of the assault team at 59 Phan Than Gian Street, the home of Mrs. Nguyen Thi Phe, a veteran Communist agent who ran an auto repair shop next to her home, just four blocks from the Embassy. The 15 sappers unpacked their weapons and dressed in black pajamas with a red sash around one arm. They had trained to breach the Embassy’s outer perimeter with explosives and attack with rifle fire, satchel charges and rocket propelled grenades. They were ordered to kill anyone who resisted but to take prisoner anyone who surrendered.

The Embassy attack was to be the centerpiece of a larger Saigon offensive, backed up by11 battalions totalling 4,000 Viet Cong troops. The operation’s other five objectives were the Presidential Palace, the national broadcasting studios, South Vietnamese Naval Headquarters, Vietnamese General Staff Headquarters at Ton Son Nut Airbase, and the Philippine Embassy. The goal was to hold these objectives for 48 hours until other Viet Cong battalions could enter the city and relieve them. North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front leaders expected (or hoped) that a nationwide uprising to overthrow the government of South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu would take place.

Of all the targets, the U.S. Embassy was perhaps the most important. The $2.6 million compound had been completed just three months earlier. The six-story Chancery building loomed over Saigon like an impregnable fortress. It was a constant reminder of the American presence, prestige and power. Other key military and political targets were slated for attack in South Vietnam, like Nha Trang, Buon Ma Thout and Bien Hoa, but most Americans couldn’t even pronounce their names, let alone understand their importance. A successful attack on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, however, would instantly convey shock and horror on an American public already weary of the war, and could turn many of them against the war.

Public Relations Blitz

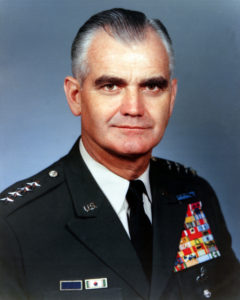

President Lyndon B. Johnson conducted a massive public relations blitz at the end of 1967 to convince Americans that the Vietnam War was nearing a conclusion. General William Westmoreland, the U.S. military commander in Vietnam, was ordered to support the President’s progress campaign. In November 1967, Westmoreland told NBC’s Meet the Press that the U.S. could win the war within two years. He then told the National Press Club, “We are making progress, the end begins to come into view.” In his most memorable phrase, Westmoreland (derisively known as “Westy” to many members of the press corps) claimed to see “some light at the end of the tunnel.”

The massive public relations campaign overwhelmed voices of other experienced American observers who foresaw disaster. General Edward Landsdale had been a senior American advisor to the South Vietnamese government starting in the mid-1950s; he was an expert on unconventional warfare and still senior advisor to the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. In October 1967, Landsdale wrote to U.S. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, “Hanoi policy makers saw the defeat of French forces in Vietnam as having reached its decisive point through anti-war sentiment in France than on the field of battle in Vietnam. [The battle of] Dien Bien Phu was fought to shape opinion in Paris, a bit of drama rather than sound military strategy.”

Landsdale warned that Hanoi was about to follow a similar plan to “bleed Americans” because it believed the American public was vulnerable to psychological manipulation in 1968. It was an accurate prediction; despite Landsdale’s inability to exert influence on policy iat that time, he had a better grasp on what was happening in Vietnam than Westmoreland or Bunker – or President Johnson.

Detoured to Khe Sanh

As an ABC News TV correspondent I was sent to the U.S. base at Khe Sanh, located in the northwest corner of South Vietnam, in the weeks before Tet.The base had been under siege by Communist forces and General Westmoreland was predicting a major offensive there, where the Communists would seek to repeat the French military loss at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Since 1968, a majority of U.S. military analysts have suggested the enemy attacks at Khe Sanh were part of a ruse to draw American military forces away from South Vietnam’s population centers, leaving them open to successful attacks at Tet. Khe Sanh became a metaphor for Westmoreland’s mismanagement of the war.

My cameraman and I were covering the ongoing battle at Khe Sanh. A massive attack on January 30 sent us diving into a trench for protection from incoming mortars and rockets; the effort saved our lives but broke the lens of our camera. We were forced to return to Saigon for a replacement. I thought we would miss the expected military push on Khe Sanhbut flying back to Saigon on the C-130 milk run, it seemed like all of South Vietnam was under attack. As we took off from Da Nang, enemy rockets fell on the runway. Flying south along the coast, we could see almost all the seaside enclaves under attack – Hoi An, Nha Trang and Cam Ranh Bay. It was a clear night, and as we passed over the besieged cities, we could see fires burning and hear on the military radio frequencies the calls of besieged U.S. troops.

The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army battle plan for the Tet Offensive called for coordinated surprise attacks throughout the country, but their plans were seriously compromised by a misunderstanding concerning the attack date. The Communist forces in the Northern provinces mistakenly planned the attack for January 30, whereas zero hour in the Southern provinces was understood to be January 31. As a result, I was in the unique position of watching the Tet Offensive unfold from the North to the South.

Convoy to the Embassy

At 2:30 AM, the Ba Den’s sapper unit loaded into a taxi cab, a Peugeot truck and an Embassy car. Guiding them to the target was Nguyen Van De, the Embassy driver, a long-time employee who Embassy staff had nicknamed “Satchmo.” Several of the sappers hid in his trunk. Driving with their lights out, the convoy approached the Embassy night gate on Mac Dinh Chi Street and fired their AK-47 assault rifles at two American sentries guarding the gate. Specialist 4 (SP4) Charles Daniel and Private First Class (PFC) William Sebast returned fire with their M-16 assault rifles, then ran through the steel gate and locked it. At 2:47 AM they transmitted “Signal 300” over the MP radio net to alert everyone that the Embassy was under attack. The sappers placed a 15 pound satchel charge against the eight foot high embassy wall, and the explosion created a hole three feet wide. The first two sappers crawled through the breach but were immediately killed by Daniel and Sebast’s rifle fire.

Daniel shouted into his radio, “They’re coming in! They’re coming in! Help me! Help me!” as more sappers came through the hole. In an exchange of gunfire, both Daniel and Sebast were killed, the first two Americans killed in the battle for the Embassy.

The sappers made a concerted effort to break into the Chancery firing rocket propelled grenades through the heavy wooden doors and following up with hand grenades. Several U.S. Marines were wounded by shrapnel and fell behind the Chancery door. Few of the Marine or MP guards were armed with M-16’s or other automatic weapons. One Marine fired a shotgun from the roof at the next wave of sappers entering through the hole in the wall. When the shotgun jammed, he continued to fire his .38 caliber revolver. Other American troops began to take up positions on nearby rooftops, giving them some control of the streets and the sappers inside the compound. Now trapped in the compound and being shot at from multiple directions, the attackers hunkered down behind large concrete flower pots on the Embassy lawn.

At about 3 AM, chief U.S. Embassy spokesman Barry Zorthian, at home a few blocks from the attack, started calling news bureaus; he had few details but told them the Embassy was under attack and there was heavy fire. ABC News bureau chief Dick Rosenbaum then called me around 3:30 and told me – just back from Khe Sanh – to find out what was happening. The ABC bureau, located at the Caravel Hotel, was only four blocks from the Embassy. We headed there in the ABC News jeep but did not get far. Just off Tu Do (now renamed Dong Khoi) Street, three blocks from the embassy somebody opened up on us with automatic weapons. It was impossible to tell who it was – Viet Cong, South Vietnamese Army, Saigon police, or U.S. MP’s. A couple of rounds pinged off the hood of the jeep. I killed the jeep’s lights and reversed out of range. We returned to the ABC News bureau to await dawn.

At 4:20 AM, Military Assistance Command-Vietnam (MACV) issued an order instructing the 716th Military Police Battalion to retake the compound. When the MP officer in charge arrived at the scene, he concluded that U.S. forces had the Embassy surrounded and the sappers trapped inside its walls. He was unwilling to risk lives of his men in a dangerous night assault against an enemy he knew could not escape, so he ordered his men to settle in and wait for morning.

At about 5:00 AM, a U.S. Army helicopter carrying reinforcements from the 101st Airborne Division attempted to land on the Chancery roof. As the chopper hovered before touching down, the surviving sappers opened fire. Afraid of being shot down, the helicopter chief aborted the mission and flew quickly away from the building. Lieutenant General Frederick Weyand, the Commander of III Corps (one of the four major military sectors designated by MACV), was monitoring the Embassy fight and agreed there was nothing to be gained by risking another night helicopter landing into a hot landing zone. He ordered a halt to air operations until daylight.

At first light, my cameraman and I walked to the Embassy. As we approached, I heard heavy firing and saw green and red tracer bullets cut into the pink sky. Near the Embassy, we joined a group of U.S. MPs moving toward the Embassy front gate. I started my tape recorder for ABC Radio as the MPs loudly cursed the South Vietnamese troops for running away after the first shots. Lying flat in the gutter that morning with the MPs, we didn’t know where the Viet Cong attackers were holed up or where the fire was coming from, but we knew it was the “big story.”

Several MPs rushed past, one of them carrying a Viet Cong sapper piggy-back style. The sapper was wounded and bleeding. He wore black pajamas and, strangely, had an enormous red ruby ring on his finger. I interviewed the MPs and recorded their radio conversation with colleagues inside the Embassy gates. There was no doubt they believed the Viet Cong were in the Chancery building itself. Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett crawled off to find a phone and report the MPs’ conversation to his office.

Just One Mag

Sporadic gunfire continued around the Embassy and one by one the sappers were either wounded or killed. I lay flat on the sidewalk in front of the Embassy as bullets ricocheted around. I found I was lying next to a seriously wounded sapper wearing black pajamas and a red arm band and bleeding from multiple wounds. Years later after reading declassified interrogation reports of the three prisoners, I discovered the wounded sapper lying next to me was Captain Nguyen Van Giang, alias Ba Den, who had lit firecrackers in the Saigon market the night before his mission and was one of the first through the hole blasted in the wall. Giang spent the remainder of the war as one of three prisoners of the Embassy attack in the infamous French-built prison on Con Dao Island just off the Southeast coast of South Vietnam.

Around 7:00 AM, Army assault helicopters land thirty-six heavily armed paratroopers from the 101st Airborne on the Embassy roof. The troopers quickly started to clear the building from top floor down searching each office for possible Viet Cong infiltrators. On the ground, MPs from the 716th stormed the front gate. My cameraman and I followed them onto the lawn which was littered with the bodies of dead and dying Viet Cong. I stepped over the Great Seal of the United States which had been blasted off the Embassy wall. We rushed into the once elegant Embassy garden where the battle had raged. It was, as UPI’s Kate Webb later described, “like a butcher shop in Eden.”

We paused to assess our film supply. “Okay, Peter how much film have we got left,” I shouted to my cameraman. “I’ve got one mag,” he replied. “How many do you have?” I had no mags left. “We’re on the biggest story of the war with only one can of film,” I groaned. “So it’s one take of everything including my stand-upper” – a TV reporter’s closing remarks.

VC green tracer bullets still stitched the night sky as red tracers from the U.S. weapons arced down from the Embassy roof and from across the street. The MPs took three wounded sappers prisoner and marched them off for interrogation. Nguyen Van De, the Embassy driver who had aided the sappers, lay dead on the lawn along with another armed Embassy driver. Two other Embassy drivers died as well. Orders crackled over a field radio from an officer inside the Chancery. “This is Waco, roger. Can you get in the gate now? Take a force in there and clean out the Embassy, like now. There will be choppers on the roof and troops working down. Be careful not to hit our own people. Over.”

Colonel “Jake” Jacobson, the CIA chief-of-station assigned to the Embassy occupied a small villa adjacent to the Embassy. He suddenly appeared at a window on the second floor. An MP threw him a gas mask and a .45 caliber Army pistol. Surviving sappers were believed to be on the first floor and would likely be driven upstairs by tear gas. The last VC still in action rushed up the stairs, firing blindly at Jacobson but missed. The colonel later told me, “We both saw each other at the same time. He missed me and I fired one shot at him point blank with the .45, taking him down.” The battle was over.

At 9:15 AM, the U.S. officially declared the Embassy grounds secure. Scattered about the grounds were the bodies of 12 of the original 15 sappers, two armed Embassy drivers who were considered double agents and two drivers killed by accident. Five Americans were dead, including four Army soldiers: Charles Daniel, Owen Mebust, William Sebast, Jonnie Thomas; and one U.S. Marine, James Marshall.

Westmoreland Briefs

At 9:20 AM, General Westmoreland strode through the gate in his carefully starched fatigues, flanked by MPs and Marines who had been fighting since 3 AM. Standing in the rubble, Westmoreland held a briefing for the press. “No enemy got in the Embassy building. It’s a relatively small incident. A group of sappers blew a hole in the wall and crawled in. They were all killed.” He cautioned us, “Don’t be deceived by this incident.” Westmoreland’s relentless optimism struck most of us reporters as surreal, even delusional. Most of us there had seen much of the fighting. The General was still spinning that everything was just fine. In the meantime, thousands of U.S. and South Vietnamese troops were fighting hard to take back the four other Saigon targets the VC had occupied – as well as the City of Hue and other targets of the offensive around the country.

Also, contrary to Westmoreland’s briefing, it was not correct that all of the 15 sappers were killed. Three were wounded but survived. Army photographers Don Hirst and Edgar Price, and Life Magazine’s Dick Swanson took dramatic photos of the wounded sappers being led away by 716th Battalion MPs, before being turned over to the South Vietnamese – and never heard from again during the war. No one admitted that some sappers survived, and it was a closely guarded secret that at least two of the dead Embassy drivers were Viet Cong agents.

The Embassy siege showed the effectiveness of U.S. Marines and Military Police, non-tactical troops fighting as infantry without benefit of heavy weapons or communication to overcome an enemy.

A TV Report Stand-Upper

Using our last 30 feet of film, I recorded my “stand-upper.”

“Since the Lunar New Year, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese have proved they are capable of bold and impressive military moves that Americans here never dreamed could be achieved,” I said. “But whatever turn the war now takes, the capture of the U.S. Embassy here for almost seven hours is a psychological victory that will rally and inspire the Viet Cong.”

A rush to judgement? Perhaps, but I was on an hourly deadline and ABC expected the story as well as some perspective, even in the early hours of the offensive – a first rough draft of history. Still my instant analysis never made it onto ABC News. Worried about editorializing on a sensitive story, a senior producer in New York killed the on-camera close. Ironically, my closer ended up in the Simon Grinberg library of ABC out-takes and was later discovered by director Peter Davis and used in his film “Hearts and Minds.”

The rest of our story package fared better. The film from all three networks arrived on the same plane in Tokyo for processing and editing, causing a mad scramble to be the first film on the satellite for the evening newscasts in the U.S. Because we only had 400 feet to process and cut, ABC News made the satellite in time and the story led the evening news. NBC and CBS missed the satellite deadline and had to run catch-up specials later in the evening.

An Information Curtain Falls

Our group of 50 journalists in the Embassy compound were then escorted out and the gates were locked. An information curtain descended around the Embassy for the following weeks. No interviews were allowed with Marines or MP’s who had fought the Embassy battle and won. Journalists were told the only comment on the Embassy battle would come from the State Department or White House, and that an investigation was under way and would be released in due course. That report – if there was ever such a report – has yet to be declassified. Without access to the stories of the American defenders of the Embassy, their heroism went largely unreported, thus increasing the public perception that the Tet Offensive had been a U.S. defeat instead of the military victory it actually was.

In March 1968, just two months after Tet, a Harris poll showed that the majority of Americans, 60 percent, regarded the Tet Offensive as a defeat for U.S. objectives in Vietnam. The news media was widely blamed for creating the antiwar sentiment. Reseach by a senior U.S. officer in Vietnam, General Douglas Kinnard, found 91 percent of U.S. Army generals expressed negative feelings about TV news coverage. However, General Kinnard concluded that the importance of the media in swaying public opinion was largely a myth. That myth was important to the U.S. Government to perpetuate, so officials could insist it was not the real war situation to which Americans reacted, but rather the media portrayal of that situation.

Embassy Demolished, Memorials Remain

The imposing U.S. Embassy that withstood the attack fifty years ago was demolished in 1998 and replaced with a modest one story Consulate. In a garden closed to the public is a small plaque in honor of the five American soldiers who died defending the Embassy that day: Charles Daniel, James Marshall, Owen Mebust, William Sebast, and Jonnie Thomas. A few steps away, on the sidewalk outside the Consulate, is a gray and red marble monument engraved with the names of Viet Cong soldiers and agents who died there on January 31, 1968.

Three Surviving Sappers Imprisoned on Con Dao Island

The fate of the three surviving Viet Cong sappers was a closely held secret by the U.S. Embassy. Following a hot dispute between U.S. Army MPs and the South Vietnamese military as to who should have custody, the POWs were turned over to the South Vietnamese and imprisoned in the infamous old French prison on Con Dao island. U.S. Army interrogators questioned them and in 2002, the reports were declassified. If the three POWs were a fair indication of the 15 sappers who conducted the siege, it would seem they were not a highly trained elite force, but rather older soldiers of low rank, some holding down clerical and cooking duties for their units.

Ba Den, 43, was the senior survivor of the attack and among the first through the hole blown in the Embassy wall. He had been born in North Vietnam and migrated south to join a Viet Cong cadre in Tay Ninh.

A second sapper prisoner was Nguyen Van Sau, alias “Chuck,” the third man through the wall hole. Shot in the face and buttocks, the 31 year-old Buddhist was captured by MPs at first light. Sau was born on a small farm near Cu Chi and was forced to join the VC when a recruiting raid entered his village in 1964 and seized 20 men. Sau’s main complaint was that he didn’t get enough to eat but remained with the VC as most of the young men from his village were also members and had endured the same hardships. With information divulged by Sau, Saigon police raided the garage where the sappers mounted their attack and arrested the owner and ten others linked to the group.

The third sapper, 44 year-old Sergeant Dang Van Son, alias “Tot,” joined the Viet Minh in North Vietnam in 1947 and was sent down the Ho Chi Minh trail. He became cook for an infantry company in Tay Ninh. During the attack, Son was wounded in the head and leg, captured by the South Vietnamese and woke up in a Saigon hospital several days later.

Ba Den was released from prison in 1975 and returned to his village North of Saigon. There was no word of Dang Van Son or Nguyen Van Sau, who are believed to have died in Con Dao prison and are buried in the vast cemetery there.

Biet Dong Committee of Ho Chi Minh City

Now that the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive and the Embassy attack is here, Vietnamese who honor the dead according to traditional custom will remember the estimated one hundred thousand Communist soldiers who died and renew their efforts to identify the burial grounds of their comrades. So it’s surprising that even top North Vietnamese field commanders had little praise for the 15 sapper martyrs of the Embassy attack.

North Vietnamese General Tran Do, in communication with the Saigon command a few days after Tet, asked, “Why did those who planned the attack on the Embassy fail to consider the ease with which helicopters and troops could be landed on the roof?” However, their boldness and bravery against such overwhelming odds has made them heroes to be remembered in Vietnam. Although in recent years there has been U.S. cooperation in identifying burial grounds of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops, there has been no recognition of a possible mass grave for the sappers killed at the Embassy.

Something Truly Stupid

Washington military analyst Anthony Cordesman has often observed, “One way to achieve decisive surprise in warfare is to do something truly stupid.” As revealed in the interrogation reports of the sapper POWs, the planning and execution of the Embassy attack was “truly stupid” and carried out by poorly trained Viet Cong, but its effects marked a turning point of the war and earned a curious entry in the annals of military history.

Another Washington military analyst, Steven Metz, explains “counterinsurgency” and why Tet became a dramatic turning point in the war. “The essence of insurgency is the psychological. It is armed theatre. You have protagonists on the stage, but they are sending messages to a wider audience. Insurgency is not won killing insurgents, not won by seizing territory; it is won by altering the psychological factors that are most relevant.”

In Vietnam, this “truly stupid” attack on the U.S. Embassy changed the course of the war. It may have been “a small incident” as General William Westmoreland claimed, but seen through the political and psychological prism of insurgency warfare, it may have indeed been the biggest incident of the war.

Pray tell, what possible psychological excuse could have justified the American invasion of Vietnam? It was clearly a continuation of French colonialism. The toll was over a million Vietnamese casualties and tens of thousands of Westerners (French and American). It confirmed that “war is a racket”, so elequently phrased in 1935 by General Smedley Butler after his retirement and hinted at in 1960 by General (and President) Dwight Eisenhower when he warned of the “military/industrial complex”.

Thank you, Don.

Where did the other 4000 who were supposed to relive those sappers go too? Ghost figures I guess. I was in Tet 70/71 and only the bush experienced guys would be put on 30 nights guard duty in the small bases and it was OK duty since we had hot meals and a bed everyday. Charlie came earlier in the year and blew our ammo dump up so he was happy enough not to surprise us at tet time, which was OK by me. Thanks for the flashback Consortium.

Quisiera estos artículos en español.

Quisiera estos artículos en español. Gracias.

First hand replorting by an experienced correspondent whose work with me in Indonesia left no doubt of North’s skills and reliability.

Frank Palmos (Scarborough, Australia, Jan 31’18

Don, great story, well done.

hebat http://www.agens128.org

Thank you Don North for this review. Probably during our lifetime, the controversy of the Vietnam War will not be decided but now we’re in the phase of analysis where personal and classified documentation is coming to light so thank you Don North for this valuable remembrance.

I personally decided on my stance sometime in 1965 but here I want to point out to CN readers the mention of Edward Lansdale in this article, and I’ll provide a link that interested readers may look at that I would encourage to carefully follow.

I can’t think of a more influential individual on my generation than Edward Lansdale. If one looks carefully behind the scenes in nearly every controversial event, one will find Edward Lansdale. I first became aware of him when I read Col. Fletcher Prouty mention that he thought he could identify Lansdale on the scene at Dealy Plaza.

It was Lansdale philosophy that Communism could only be stopped by Democratic Revolution. A major mistake in my estimation. He supported a clear bridge into civilian warfare that is unacceptable. Recently I read a review of a new book by Max Boot in The NY Times “The Road Not Taken” which seems to indicate that if a more “limited war” had been fought in Vietnam there might have been a better outcome which, for me, is a major misconception underlying most Neocon thinking so some lessons appear to never be learned…

http://spartacus-educational.com/COLDlansdale.htm

Another great article from Don North. To Mr. Van Noy: I also was going to comment on Lansdale and some of his shady doings and also how he had ingratiated himself with the Vietnamese. I once saw an interview with just him much later on in life and all I could think whilst watching was how much information he held close to the vest during it. I cannot recall for sure if it was on Daniel Ratican’s site (ratville.org) or elsewhere. And just what was he doing in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963?

I agree with your pointing out what Landsdale meant in history. Nice addition to the thread. I also agree that a more limited war might have been a better outcome. That is reduced to the logic that the best outcome would be no war at all. I fully support that idea. I see no reason we went to war in Vietnam except perhaps the Vietnamese nation had all the qualifications for a nation to be attacked chief among the reasons it had no nukes. The US has a single override to its schemes to wage foreign wars since WWII. The override is whether or not the nation being scouted as a combat theater has nukes. If the answer is yes then they put the brakes on the war. If the answer is no then the planned war is green-lighted.

If there are any questions at this point as to why North Korea is developing nuclear weapons capable of striking the US you must have not realized what message our foreign policy transmits to other nations. Any nation opposed to the US and also especially on our hit list such as Iraq and Libya which had no nukes were easy marks for the US war machine.

North Korea’s theatrical displays of nuclear might are motivated to project the notion that they have a vast array of nuclear weapons and will strike without warning any threat they perceive. They do this in the hope they will join the ranks of the untouchable rouge states like Pakistan which also has lots of Nukes and also is not a target of US military aggression.

Who knows? Perhaps North Korea’s Nuke program will land it a seat as one of the allies of America just like Pakistan.

If I were North Korea’s leader I would be building atomic bombs. So would you. We did it to protect ourselves as did many other nations.

The ability to inflict lethal damage on an enemy is a pure primal fantasy curbed by the realization that in doing so the pure primal fantasy of the attacker will shortly be showing its last appearance at a theater near you.

The nuclear balance of terror has worked since the beginning of the cold war and although many other nations have entered the nuclear club and the proliferation of nuclear states has been fought hard against in a somewhat losing way, there has not been a nuclear war.

Turns out every nation would really rather to slog on in their own way facing many enemies and mismanaging affairs at home but still existing and having a country to rule with an iron fist rather than engaging in suicide.

All the drama and hype over North Korea is just meant to drive spending in our nuclear arsenal to make a ton of cash and preserve the nuclear weapons industry which we actually need to keep being a credible threat.

Of course the problem is delivering that first strike and denying the target the means to retaliate.

But hey that is what the internet was meant for!

Everything you wrote CitizenOne is very true, but for all of what you said this is why China replacing U.S. bombs with OBOR infrastructure work, is a much better worldwide PR campaign. I digress that my whole life I have advocated for such Soft Foreign Policy mindsets to guide our American projects, but as I said I digress. Joe

Never underestimate the power, and dedication, of the indigenous to defend their homeland.

One of the things that has always amazed me about the average American is their inability to put themselves into someone else’s shoes. Who in the good ol’ USA would tolerate foreign troops on our soil? I doubt anyone- left, right, or center. The one thing that would unite our citizenry, even in these crazy times, would be an actual foreign invasion. Yet we have over 800 bases around the world, and the average American thinks we are welcomed, or just doesn’t think about it at all. It is just an unbelievable failure of imagination.

When I was stationed in Norfolk Virginia while in the Navy, I got the distinct impression that the good citizens of Norfolk didn’t want us there. To boot over half the town was, or is, Navy. So Skip, this unwantness May be happening whether we realize it or not. Joe

Well, I think one of the reasons most people have become so insensitive to our multiple wars is there’s no draft, so they don’t feel threatened on a personal level, since their sons and daughters will not be asked to put their lives on the line for their country, although they will stand and applaud those that do. Those that enlist in military service see it as the only way to move forward in their lives, with fewer options now for young adults then there was in the 60’s and 70’s. At the time of the Vietnam war many people had televisions at that point, and there was a significant amount of coverage portraying many aspects of the war in all it’s brutality that the American people could see, since their was “inadequate” government control on the media. I think the mainstream media, and various weekly publications also brought the war home. No doubt it was the key factor that made Johnson decide not to run for reelection.

In these last 15 years I don’t see the brutality of these wars splashed across TV channels, and the media has actually become complicit in pushing our wars. The anti-war movement that swept the country after our entry into the Iraq war got little coverage. I remember, since I marched to protest that war, then looked in newspapers, and basically there was either a mere mention, or no coverage at all.

The media have been cowed.. Their newsrooms replaced with carefully scripted approved narrative which removes any negative coverage not favorable to the war department. In a sense, the media have become clones of General Westmoreland with his shiny starched shirt spouting official optimism for all things military.

The conservative echo machine also went into overdrive branding CNN the Communist News Network. Appearances by military leaders were carefully controlled and the phrase that revealing information as to strategies and tactics were off limits were used as a cover to dodge questions aimed at getting information about conditions in the field of battle.

In a real sense the argument that publishing information about what is going on is a bad thing has a logic to it. Certainly our enemy tuned in to CNN and was trying to glean as much information as possible and no spies planted in America were needed since telecommunications technology could transport CNN into every corner of the enemies territory far away in some foreign land. Technology was as much a reason for the clampdown as was the desire to deprive Americans of negative news coverage which might cause the type of psychological effects the generals feared in 1968.

Both reasons were and are still the main reasons we do not hear the kind of front line coverage which was possible in Vietnam. But it is likely the effect on depriving Americans of information has the greatest effect while the denial of secret plans to our enemy plays a significant but lesser part.

In a way this does make sense and the psychology of the crowd effect is real. It underlies the effect of home team advantage. The visiting team facing boos for every goal and jeers for every misstep coupled with the wild cheering for the home team for every gain no doubt has an effect on players. Reporters can run with stories they feel are important without regard for the psychological effects on the opposing forces. One can honestly ask that if a controlled media and press creates a real psychological advantage to the US forces by delivering a crafted message regardless of the factual accuracy of the story then as a member of our national interest why shouldn’t they be controlled to deliver that message. After the whole country is at war not just a part of it.

This thinking however runs afoul of history and which side will be ultimately judged as the justified side and the unjustified side of military actions and wars. If we all cannot be presented with facts and agree the war is justified then probably it isn’t. That may be bad news for the war department but it is a reality check on their battle plans and actions. If a population rises in protest against the government because they have been presented with the truth then perhaps the government is on a wrong course.

The key here is balance. Reporters must not side with one camp and must present the various positions and arguments equally and fairly and leave it up the the American People to decide which viewpoint is correct or which is the right course to follow. That is not to say that he said she said is what I am talking about. The story should never be just statements with no analysis. Reporters should investigate every position and call out when it is sound as well as unsound. The debate on Global Warming is a current hotbed of media control and stories which state some scientists are concerned but they are being challenged by other scientists who dispute the theory is a fine starting line but the article is only newsworthy if it goes further to explore the basis for the opposing claims and reports on the findings of that investigation.

That is what investigative journalism is meant to be. It is not supposed to be propaganda for one side. It is supposed to present the opposing arguments and explore them and to report the findings in an unbiased way.

Robert Parry did this his whole life and was dedicated to the profession of investigative journalism. He was an oasis in a desert of propaganda for one side of the story which our main stream media has become.

I hope the pendulum has reached an apex and will be damped and attenuated as it again closes in on neutrality and objective sound reasoned arguments stopping the swinging cycle from one extreme to the other.

Always been, the wars are against the “common man,’ for the “elites.”

Wars are always occurring at some level, most unseen or unacknowledged (as is the case with “sanctions,” an actual statement of war in other clothing). Visibility, or hotness, comes to be when internal pressures are rising; wars are, after all, the means for controlling and rallying the citizenry. These are mostly the aims of the aggressors (to help disguise/shield the sights of ugly aggression from their masses’ eyes); though on the other side of the coin, the defenders’, there’s also a push to unite, but this is for common protection, a vastly more moral standing (firmly recognized, but, sadly, less and less committed to by the “International Community” due to it being controlled by the aggressors themselves).