Traditional U.S. history downplays Native people who settled the land and Africans enslaved to cultivate it while glorifying European whites and ignoring when the “other side” won, as on Christmas Day 1837, writes William Loren Katz.

By William Loren Katz

On Christmas Day in 1837, Africans and Native Americans who formed Florida’s Seminole Nation defeated a vastly superior U.S. invading army bent on cracking this early rainbow coalition and returning the Africans to slavery. The Seminole victory stands as a milestone in the march of American liberty.

Though it reads like a Hollywood thriller, this amazing story has yet to capture public attention

Despite its significance, it does not appear in school textbooks and social studies courses, Hollywood and TV movies.

This daring Seminole story begins around the time of the American Revolution of 1776 as 55 “Founding Fathers” were writing the Declaration of Independence with its noble words about all people being “created equal [and] endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

About the same time, Seminole families, suffering ethnic persecution under Creek rule in Alabama and Georgia, fled south to seek independence. African runaway slaves who earlier had escaped bondage welcomed them to Florida. The Africans did more than offer Seminole families a haven; they taught them methods of rice cultivation the Africans had learned in Senegambia and Sierra Leone in Africa.

Then the two peoples of color forged a prosperous bi-racial nation and a military alliance strong enough to withstand European invaders and slave-catchers. The Seminoles were led by such skilled military figures and diplomats as Osceola, Wild Cat and John Horse.

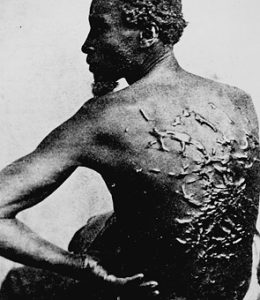

This alliance drove U.S. slaveholders to sputtering fury since these armed Black and Indian communities lived a stone’s throw from what was then the southern U.S. border. The slaveholders claimed that the Seminole unity – along with the community’s relative prosperity and guns – posed a lethal threat to the plantation system. After all, here was a beacon that enticed more Africans to escape from bondage and offered them a military base for protecting their freedom. Further, these peaceful and successful agricultural communities destroyed the slaveholders’ myths claiming Africans required white control.

The U.S. Constitution of 1789 embraced slavery and protected slaveholder interests, even letting them count their slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of representation in Congress, thus enhancing the political power of slave states. From George Washington to the Civil War, slave owners sat in the White House two-thirds of the time, the same proportion of time that slaveholders were Speakers of the House of Representatives and Presidents of the U.S. Senate. Further, 20 of 35 U.S. Supreme Court Justices owned slaves.

The War on Freedom

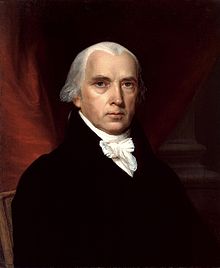

With the support of their Northern trading partners – merchants and businessmen, and the politicians who served them – slaveholders directed U.S. foreign policy, keeping up a drum-beat of demands for U.S. military intervention in Florida. In 1811, President James Madison, himself a slave owner, authorized covert U.S. invasions by slave-catching posses called “Patriots.”

Then in 1816, General Andrew Jackson ordered General Gaines to attack the Seminole alliance and “restore the stolen negroes to their rightful owners.” A major U.S. assault began on hundreds of people of color living in “Fort Negro” on the Apalachicola River.

As U.S. Army Colonel Clinch sailed down the Apalachicola he wrote: “The American negroes had principally settled along the river and a number of them had left their fields and gone over to the Seminoles on hearing of our approach. Their cornfields extended nearly fifty miles up the river and their numbers were daily increasing.”

When a heated U.S. cannon ball hit “Fort Negro’s” ammunition dump, the explosion killed most of its more than 300 defenders. The survivors were marched back to slavery. Then in 1818, General Jackson invaded and claimed Florida. The United States “purchased” it [$5,000,000] from Spain in 1819, and sent a U.S. army of occupation for “pacification.”

But suddenly the U.S. faced the largest slave revolt in its history, its busiest “underground railroad” station, and the strongest African/Indian alliance in North America. The multicultural Seminoles carefully moved families out of harm’s way from 1816 to 1858 as they resisted the U.S. through three “Seminole wars.” Today many Seminoles still claim they never surrendered.

In June 1837, Major General Sidney Thomas Jesup, the best-informed U.S. officer in Florida, described the danger posed by the Seminole alliance: “The two races, the negro and the Indian, are rapidly approximating; they are identical in interests and feelings. … Should the Indians remain in this territory the negroes among them will form a rallying point for runaway negroes from the adjacent states; and if they remove, the fastness of the country will be immediately occupied by negroes.”

A Disputed ‘Victory’

Then on Christmas Day of 1837, 380 to 480 Seminole fighters gathered on the northeast corner of Florida’s Lake Okeechobee ready to halt the armies of Colonel Zachary Taylor, a Louisiana slaveholder and ambitious career officer. He was building a reputation as an “Indian killer.” Taylor’s troops included 70 Delaware Indians, 180 Tennessee volunteers, and 800 U.S. Infantry soldiers.

As Taylor’s army approached, Seminole marksmen waited perched in trees or hiding in tall grass. The first Seminole volley sent the Delaware fleeing. Tennessee riflemen plunged ahead until a withering fire brought down their commissioned officers and then their noncommissioned officers. The Tennesseans fled.

Then Taylor ordered the U.S. Sixth Infantry, Fourth Infantry and his own First Infantry Regiments forward. Pinpoint Seminole rifle fire brought down, he later reported, “every officer, with one exception, as well as most of the non-commissioned officers” and left “but four . . . untouched.”

On that Christmas Day, Colonel Taylor counted 26 U.S. dead and 112 wounded, seven dead for each slain Seminole, and he had taken no prisoners. After the 2½-hour battle, the Seminoles took to their canoes and sailed off to fight again.

The battle of Lake Okeechobee became the most decisive U.S. defeat in more than four decades of Florida warfare. But after his survivors limped back to Fort Gardner, Taylor declared victory – “the Indians were driven in every direction.” The U.S. Army promoted him and he later became the 12th president of the United States.

The battle of Lake Okeechobee was part of the Second Seminole War that took 1,500 U.S. military lives, cost Congress $40,000,000 (pre-Civil War dollars!) and left thousands of American soldiers wounded or dead of disease. Seminole losses were not recorded.

The truth of what happened at Lake Okeechobee remained buried. When President Taylor died in office, former Congressman Abraham Lincoln memorialized him on July 25, 1850. “He was never beaten,” Lincoln said, adding, “in 1837 he fought and conquered in the memorable Battle of Lake Okeechobee, one of the most desperate struggles known to the annals of Indian warfare.”

A century and a half later, noted Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote in The Almanac of American History: “Fighting in the Second Seminole War, General Zachary Taylor defeats a group of Seminoles at Okeechobee Swamp, Florida.”

The United States needs to face its past. Americans of all ages have a right to know and to celebrate the freedom fighters who built this country, all of them. Our schools, children, teachers and parents deserve to learn about a daring Christmas Day battle that has been too long buried in lies and distortions.

This 2016 copyrighted essay is adapted from William Loren Katz, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage [Atheneum, 2014 revised edition]

Who woulda believed – Dishonest Abe.

Propaganda is propaganda. Propaganda, when written and placed in record is not history. It becomes part in history, but it does not become history because it is bullshit. However much it may be asserted history, or may be believed by any to be historically ‘true’, it is, and remains, bullshit added to history.

It makes no difference whether blathered bullshit is “white” narrative, “black” narrative, “people of color” narrative, “rainbow” narrative, or any other group-focus narrative. Narrative is story, is “us-inflating” bullshitting, is propagandizing. It adds crap to history. It adds more garbage that must be dug through, turned over and thrown out to uncover the factual kernals of event that provide solid record elements useful to defining historical records for events.

Whether it is lying about Columbus discovering the Americas, or setting foot on them (which he did not), or having any but negative and destructive influence, or beginning from nineteenth century propaganda scare-narrative to build a narrative of the bogey-specters of that propaganda narrative being “real” and “real” “opponents” in a war they were only scary phantasms of the propaganda of, the result is a load of crap dumped in the historical stream. More flotsam and pollution muddying the historical record.

“people of color”? Not much of real importance ever changes in the united states of america.

Thanks very much for that piece, Mr. Katz. I observe from your admirable Amazon author page – https://www.amazon.com/William-Loren-Katz/e/B000APFPWI/ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1?qid=1482809312&sr=1-1 – that you have had decades of experience garnering reactions to the telling of hidden/repressed histories. And I wanted to ask you about good thoughts or references you might have in relation to that.

I am interested in trying to cultivate more explicit discussion of the true reasons many people have, and the reasons they give, for often desiring that these histories stay hidden. I mean to include things someone might say like “For the sake of our national image & unity….” or variations on that, and other unstated attitudes. My hope is that more explicit discussion can help people to see recurrent patterns, and re-examine their validity. At the same time, folks who like to turn over dark corners often work from the assumption that priority for truth is a strong, shared value….and that assumption may often be wrong, in practice. Maybe more needs to be said about accurate historical awareness being good for people at large, even if they feel like their tribe is enjoying the sunny mainstream.

Dec 25, 2016 The 12 Days of Anarchist Christmas

Song featuring: Jordan Page, Luis Fernando Mises, Jeffrey Tucker, Jeff Berwick, Macey Tomlin, Dayna Martin & family, Nathan Freeman & family w/ Erika Harris and Juan Galt, Eric July, Roger Ver, Dan Dicks & Molly Poepoezeezoe, Adam Kokesh and Charlie Shrem

https://youtu.be/CxMmO9X6E3M

February 23, 2015 America Has Been At War 93% of the Time – 222 Out of 239 Years – Since 1776 The U.S. Has Only Been At Peace For 21 Years Total Since Its Birth

Below, I have reproduced a year-by-year timeline of America’s wars, which reveals something quite interesting: since the United States was founded in 1776, she has been at war during 214 out of her 235 calendar years of existence. In other words, there were only 21 calendar years in which the U.S. did not wage any wars.

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article41086.htm

Brian: Thank you very much for this history. I am working on a similar history and yours will be a great help.

You are very welcome Bill Bodden!

Another fine entry in the “people’s history” series is Williams’ “A People’s History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom” (New Press, 2006). It is especially interesting for its documenting of southern white resistance to the Confederacy, and the tyranny of the Richmond regime. The patroller system set up to catch runaway slaves was turned against whites who deserted the insurgent forces; the Home Guard was the closest thing ever to an American Gestapo, hunting down, torturing, even murdering dissidents.

The enormous output of “revisionist” American historians in the last six decades is a perhaps unintended consequence of the GI Bill. By its provisions a college education was available to millions of ordinary Americans for the first time. The study of American history in academia, formerly the self-congratulatory hobby of wealthy men of leisure, would now expand to include the contributions of the other 99%. At last their stories could be told, along the truths about those silenced by racism and attempted genocide. The study is still in its infancy, with exciting new material being published every year.

Right on about some southerners who were Pro Union aka anti confederate. Thousands of southerners joined the Union army. Thousands of southerners were draft resisters. Many became doctors teachers and ministers to avoid the draft

Thank you William Loren Katz for this remarkable history of the Seminole’s noble history and fight against slavery. And the courage of Seminole and escaped slaves who joined together to form a peaceful settlement and to fight against the predators.

The viciousness of the leaders written about so glowingly in American history books has been swept under the rug for too long. No wonder even today we tolerate mindless aggression and brutal regime change.

In one of his talks Andrew Bacevich said, if I recall correctly, that “American exceptionalism” is hard wired into the American psyche. I hope that’s not true. I hope that it’s merely been bred into the American psyche and rewriting history to tell the actual truth, might help loosen it a bit before it all “ends with a bang’.

The United States needs to face its past. Americans of all ages have a right to know and to celebrate the freedom fighters who built this country, all of them. Our schools, children, teachers and parents deserve to learn about a daring Christmas Day battle that has been too long buried in lies and distortions.

James Loewen has written several books exposing the lies that have been told to the American people for years. “Lies my teacher told me” is one of his books. Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States” is a classic eye-opener for people who might want to know the truth. Any books from the pop-historians and other hagiographers should be regarded with great skepticism.

The constant stream of lies told to the American people throughout history and continuing into the present must surely be one of the great debilitating factors influencing the nation.

Robert Dallek in “Flawed Giant” fails to tell of Lyndon Johnson’ complicity in the cover-up of the Israeli attack on the USS Liberty on June 8, 1967.

Behind the USS Liberty Cover-up: For decades, Israel has exercised strong influence over U.S. policies in the Mideast via its highly effective Washington lobby, but that power was tested in 1967 when Israeli warplanes strafed the USS Liberty killing 34 American crewmen, an incident revisited in a new documentary reviewed by Maidhc Ó Cathail. – https://consortiumnews.com/2014/11/12/behind-the-uss-liberty-cover-up/

Happy Holiday! I find it interesting that there is so much American history that was never taught in school. In my case it was very one-sided and nary a mention of all the native people that were slaughtered in the ‘building’ of the nation. I enjoyed this piece on a portion of the history of the country, a welcome relief from all the political dreariness the distresses me daily. Thanks for a excellent publication and happy new year.

So as an American you find it interesting to learn about your country that you were not taught half the history.

As a foreign student in American Universities I was constantly at odds with the American History Profs. either the history in the American history school books was erroneous and/or at times completely not there.

I.e. Columbus discovered America.

They conveniently left off the “S”. When brought to the Profs attention I was named a “nitpicker”. Well in my country in world history study I had learned that Columbus, and Italian and poor navigator, has discovered the AmericaS and had landed on the Island of Haiti, not once but twice, and taught he was in the Indies because that was what the queen of Spain had told him to go find a way to the Indies by going due West across the Atlantic. In the Atlantic is a gulfstream bringing you right at the coast of what is now called Florida, Portuguese Admiral Canaveral used that gulfstream, the place now goes by the name of Cape Canaveral which has the Kennedy Space Center which name the Washington lame heads had renamed to Cape Kennedy. It didn’t work because the residents of Cape Canaveral told Washington “go piss up a rope”. So the name was changed back to Cape Canaveral, because it was a place of historic value. Another guy looking for a shorter way to the Indies was Magellan who navigated further south and found the way around the bottom of South America which was then named Straight of Magellan. But the best route still remained the way the Dutch sailed around the bottom of Afrika with a stop at Kaapstad for rest and drinking water and food resupply. This route became shorter after Ferdinand de Lesseps completed the Sues canal.

History and Geography were my favorite subjects, and 70-years later they still are.

Ya, I had a problem at U of Wisc. St. in 69 with my history Prof. too – he was into telling what he thought was History also. After a 25 page final in which i told the Truth{ pravda} he gave me a D – It didn’t matter as months later i ended up seeing the real History in SE Asia with the US Army. After that i spent 33 years in Alaska and now I live in Russia. – where Americans – were never told the Truth about. Spasibo y Novi Goad