Exclusive: While the gridlocked U.S. political process freezes progress in the fight against global warming, Canada is considering a national tax on carbon emissions to give a boost to renewables, writes Jonathan Marshall.

By Jonathan Marshall

Canada can take credit for many great innovations, from insulin and peanut butter to Trivial Pursuit and basketball (Dr. James Naismith was Canadian). But one of its best may be a bold new nationwide policy of taxing carbon emissions to fight global warming.

The new plan, applauded by environmentalists, requires provinces and territories to begin imposing a tax of at least $10 (Canadian) a ton on carbon emissions by 2018, rising to C$50 by 2022. (In the United States, a tax of $20 per ton of emissions would raise the price of gasoline by about 20 cents per gallon.)

It’s a tried-and-true — if highly controversial — means of creating market incentives to shift consumer behavior and promote innovations that are needed to rescue humanity from the dire prospects of climate change.

More than a dozen leading Canadian CEOs — including a former president of Shell Canada — endorsed the proposal, calling it “the most economically effective way to reduce emissions and stimulate clean innovation – which will be critical to Canada’s success in a changing global economy.”

The United States has ducked the issue ever since anti-Obama Republicans and industry-funded lobbyists killed national legislation to develop a “cap-and-trade” system to limit unsustainable emissions from the burning of fossil fuels for electricity, transportation, industry and other sectors of the economy. House Republicans followed up in 2013 by voting to prohibit the government from putting any kind of price on carbon emissions.

Instead, President Obama has had to fall back on clumsy regulatory initiatives, still tangled up in the courts, to press states to reduce their carbon emissions by unspecified means.

Many experts across the political spectrum, including conservatives, business leaders and environmentalists, agree with four former Republican heads of the Environmental Protection Agency that “A market-based approach, like a carbon tax, would be the best path to reducing greenhouse-gas emissions.” They lamented that such an efficient policy was “unachievable in the current political gridlock in Washington.”

Like them, President George W. Bush’s former chief economic adviser, Harvard University’s Greg Mankiw, declared that taxing carbon emissions to curb global climate disruption is “largely a no-brainer.”

“One of the beauties of a carbon tax, for me, is that it makes a lot of other policies [and regulations] less necessary,” Mankiw told an interviewer last year. “You let the market work it out. . . A carbon tax automatically incentivizes low-carbon forms of energy, so . . . wind and solar and technologies we haven’t even heard of yet are going to have an advantage relative to coal. People will automatically start thinking that electric cars are better than gas-powered cars. . . [But] the private market won’t do the right thing unless we put the price on this scarce resource.”

Carbon emissions are now priced, one way or another, in Finland, Great Britain, Ireland, Sweden and the state of California. Carbon taxes also had a brief but effective life in Australia, until repealed in 2014.

Success in British Columbia

Canada is home to one of the greatest success stories for carbon taxes. In 2008, British Columbia, the country’s third-largest province, introduced a tax on carbon dioxide of C$10 per ton, which rose to C$30 by 2012. It covers all major fuels, including natural gas, coal and gasoline.

To make the tax political palatable, even popular, the provincial government cut business and personal income tax rates and provided tax credits for many low-income residents. By 2012, British Columbia had the lowest personal income tax rate and one of the lowest corporate income tax rates in Canada.

The environmental results were striking. Over the period 2008 to 2013 (the last year for which data are available), per capita carbon emissions plummeted 13 percent compared to the baseline period 2000 to 2007. That drop was three-and-a-half times greater than the reduction across the rest of Canada.

Following introduction of the tax, British Columbia enjoyed slightly faster economic growth than the rest of Canada as well. And a team of economists concluded in 2015 that the net impact of the tax on income distribution in the province was “highly progressive.”

For the 10 years that Canada was ruled by the Conservative Party, which drew much of its funding from Alberta’s oil and gas industry, the national government rebuffed every call to emulate British Columbia’s success.

Since the Conservatives were trounced in the last national elections, however, “ever-wide cracks” have developed “in the Conservative facade of opposition to a proactive climate change strategy,” according to Toronto Star columnist Chantal Hébert.

Ontario’s conservative leader, Patrick Brown, told a congress of party delegates in March, “Climate change is a fact. It is a threat. It is man-made. We have to do something about it, and that something includes putting a price on carbon.”

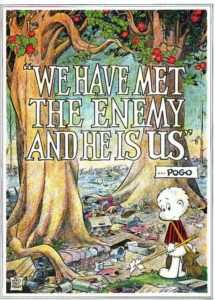

Beholden to the oil, gas and coal industries, and billionaire petrochemical producers like the Koch brothers, U.S. Republican leaders continue to insist, with Donald Trump, that global warming is a “hoax” or a matter of natural weather changes. The overwhelming consensus of climate scientists, of course, refutes their toxic disinformation and discredits their political obstructionism.

Scientific facts may not sway Washington, but if Canada makes as great a nationwide success of carbon taxes as British Columbia achieved, its example may yet trickle down south to the United States. Then, if history is any guide, Americans will embrace the policy as a smart innovation that was invented in Canada first. Just like basketball.

Jonathan Marshall is author or co-author of five books on international affairs, including The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War and the International Drug Traffic (Stanford University Press, 2012). Some of his previous articles for Consortiumnews were “Obama Flinches at Renouncing Nuke First Strike,” “Dangerous Denial of Global Warming,” “How Arms Sales Distort US Foreign Policy,” “The US Hand in the Syrian Mess”; and “Hidden Origins of Syria’s Civil War.”

Here is an good summary article about Trudeau’s carbon tax proposal, published in DeSmog Canada. It expresses a similarly hopeful view to Jonathan’s article that the tax can be built upon and something good will come of it.

http://www.desmog.ca/2016/10/03/canada-s-new-carbon-price-good-bad-and-ugly

I just found an article at a site which I had formerly respected. The Dissident Voice has provided me with some very nice essays about this and that, and it was moving up in my Bookmark listing. That was before I read this excerpt and added UNTRUSTWORTHY to the link name:

This means that “alternatives” burn more fossil fuel than the fossil fuel technologies themselves. It ain’t rocket science. Logic beats bias. “Alternatives” burn more fossil fuel than conventional energy. But it does not matter, because of “religion”.

I’ve seen this utter nonsense before from people trying to dump on nuclear power. Those people actually claimed that more energy was used in mining and refining the uranium than was produced by nuclear fission. They were well-meaning morons. Nuclear energy is extremely dangerous and impossibly expensive, but it’s not a net-negative-energy item.

The fellow who wrote that “Alternatives” burn more fossil fuel than conventional energy” presumably isn’t an idiot – he was working as a Physics Professor before he was fired from that job. Why was he fired? Because he supported the Palestinians against their mistreatment by Israel. So he wasn’t a moral leper, at least not then. So I must assume that losing his job caused him to stop doing the most basic reading/research for his articles.

Producing photovoltaic cells in the old days was a tedious and expensive procedure. Silicon had to be purified, formed into crystals, then a large chunk of these were wasted when they were sawed into wafers. One story spoke of $286/watt in the mid Fifties right after getting invented. Adjusted for inflation, that’s over $2500! Prices dropped rapidly, but in 1977 they were still $76/watt. Solar electricity generation was useful only for very special applications. I’ve got to assume the former Professor was educated in the days when these numbers were Facts, and never bothered to catch up. So he has turned into a Denier, and has published many articles about the Global Warming Religion.

Another Zachary Rule: Just because you’re totally right about one thing doesn’t mean you can’t be a damned fool in something else.

BTW, for the current situation with photovoltaic cells after more than 60 years of engineering and scientific work, there is this brief read.

http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2013-04/solar-panels-now-make-more-electricity-they-use

Jonathan, the days of outright denial of climate change are over in Canada, as is the case in much of the rest of the world. Now we live in the era of ‘deflect and delay.’

The Liberal government has maintained the Harper government’s risible carbon emissions targets. It is undertaking a slick public relations effort (cheap talk and a modest carbon tax) to win approval of pipelines and gas fracking projects following the failure of the Harper government’s crude, blustering methods to win these. Harper-style bluster no longer passes muster in a population becoming increasingly aware of the global warming emergency. But the majority of Canadians are unfortunately still willing to be soothed with lesser-evil options that can avoid the wrenching, radical downsizing of climate-wrecking emissions which science demands. The very modest emission reductions that a Liberal carbon tax will achieve will be offset by highly damaging deflection and delay. I see no progress in this, but I understand your point that this is a debatable political judgement.

Another useful commentary to explain the very modest outcomes of the Liberals’ proposed carbon tax is in today’s Toronto Star: https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/10/07/lisa-raitts-math-on-carbon-taxes-doesnt-add-up-paul-wells.html.

Roger, thanks for the link. It really illustrates both of our points: the carbon tax is very modest, and even so, it generates lots of political opposition. It would be a much tougher sell in the United States. It will be interesting to see how the vote on a carbon tax in Washington state turns out.

I respect Jonathan Marshall’s writings very much, but I’m afraid he is way off the mark in this article on Canada and climate change. Canada is proportionately one of the world’s leading climate vandals and the proposed carbon tax guideline by the new Liberal government in Ottawa does not change that by one iota.

Here is columnist Thomas Walkom writing in the Toronto Star (Canada’s largest daily newspaper) on October 2, 2016:

And there’s the problem: The carbon-price minimums Trudeau announced are just too low to work on their own.

“Not even close,” York University environment professor Mark Winfield said in an email. Winfield and other climate change experts calculate for Canada to meet its promised emission target through carbon prices, it would have to impose one of $30 a tonne now, rising to $200 a tonne by 2030.

As well, there is the question of the target itself. First enunciated last year by Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, it would have Canadian emissions reduced to 30 per cent below 2005 levels by the year 2030. (End Walkom citation.)

The carbon tax guideline by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government is a public relations exercise that is part of a broad promotion effort to significantly expand fossil fuel production and export in Canada. The government has just approved a Malaysian consortium’s proposal to build a liquefied natural gas complex on the northern coast of British Columbia to be fueled by expanded natural gas fracking in the northeast of the province. Should that LNG plan not materialize (current economics militate strongly against it), there is talk of using the same fracked gas to fuel increased tar sands production in Alberta (in the name of bogus theory that burning fracked gas is less environmentally damaging than burning oil).

In Alberta, the social-democratic provincial government elected in May 2015 is pushing for expanded tar sands production, by up to 43 per cent. The Trudeau government shares that goal. Both governments want more pipelines for expanded export of tar sands bitumen. There are such four proposed pipelines. U.S. readers will be familiar with one of those–Keystone XL. The three others are Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain to the Pacific coast, and Energy East to the Atlantic coast (some 4500-plus kilometers away!). To the great consternation of industry and the two governments, all four proposed pipelines face continued, stiff opposition.

I have long felt that Consortium News should be reporting on the U.S.’ northern neighbour. This article confirms that, albeit by way of negative example.

With those enormous mines extracting oil from the tar sands, Canada has not been one of the good guys. Those operations will have to close – pronto. Coal mines everywhere must be shut down. No new oil wells.

https://newrepublic.com/article/136987/recalculating-climate-math

Roger, I’ve never claimed that Trudeau’s plan will be sufficient; for that matter, nothing Canada does by itself will solve this global challenge. Rather, I consider it a good start and an example for other countries to follow. We have to start somewhere; don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Trudeau is simply delivering for his sugar daddies: migrants and carbon tax. Reuters is happy, the Thomsons will get richer. Soros is happy and a partner of the Canadian government.

Consortium News should know better… hence no soup for your money drive.

If Trudeau sells out on the TPP, and on the Harper-negotiated CETA it will negate any progress he has made on global warming, since the corporate tribunals will enable global warming. The Canadian legal system needs to correctly find that any of these so-called “trade agreements” run counter to the Canadian Charter repatriated by Trudeau senior and restore Canada to the real rule of law contrary to corporate parasitic power.

Trudeau is not a thinker. He’s being led by world leaders and corporate interests. He seems impressed with Obama, goes right along with whatever NATO wants. His father, who was well-read even before he became Prime Minister, who was a thinker, would have been I think on Syria and Russia’s side. No way Trudeau Sr. would have gone along with what happened in Libya, Ukraine, Iraq, nor would he have signed the TPP. He was a lawyer who would have seen right through this crap.

I don’t hold out much hope for Justin Trudeau’s leadership, too easily bamboozled. I see him as wanting to be the first to bring something in without questioning it, without thinking it through. He’s probably been told that TPP will create jobs and, without thinking again, probably believes it.

The show pony will do no such thing, we have been sold down the river. Incidentally in exactly the same manner as our friends were to the south with Barry. Your best to put YOUR house in order best as you can, at least that way there is at least a glimmer of a chance for change.

“Following introduction of the tax, British Columbia enjoyed slightly faster economic growth than the rest of Canada as well.” That “faster economic growth” is almost totally due to the fact that B.C. has SOLD THE PROVINCE TO THE CHINESE! Lock, stock and barrel, baby! Suitcases of cash flooding in from China, no questions asked. Corrupt Communist Party members laundering their ill-gotten money in B.C. real estate.

I’m torn on climate change. Of course we must be causing tremendous damage with our lifestyles (that’s a given), but there is also the other question of cyclical climate change.

http://phys.org/news/2012-01-orbits-ice-ages-axis-shifts.html#nRlv

B.W.E., your link refers to a THEOREM meant to explain The Glacial-Interglacial Cycle. Although it has intriguing correlations related to changes in Average Worldwide Temperature during a Glacial Cycle, it does not account for the approx.100,000 year length of a Glacial, nor can it explain the sudden and large rise and fall in temperature at the beginning and end respectively of an Interglacial(we are currently 12,000 years into an interglacial, all but three of the last 17 Interglacials have been 10,000-12,000years duration, two were 8,000yrs, one was 14,000). Finally the theorem does not account for the variation in Interglacial length. Most importantly for our present situation, the theorem you cite can be reduced to “amount of insolation” and so cannot explain the present warming as for the past 20 years the insolation received by the Earth is the lowest in three centuries. We are in a “cool cycle” but we are heating catastrophically. The one variable that accurately tracks warming is CO2, and to deny this is idiotic. Using a 1880-1910 Average as a baseline(worldwide instrument readings began 1880, as well as industrial CO2 emissions were at a low level) we are in 2016, so far, at 1.26C over baseline, nearly all this warming has occurred in the 21st. Century. Warming is accelerating, using past decadal rate is foolhardy. For example, 2015 was 1.01C over 1880 baseline, 0.11C over 2014, a full decade’s worth of warming in a single year. The Dec2015-Dec2016 average could be 1.28C over 1880 baseline, a 0.17C increase over 2015, that is 50% more warming than the unprecedented 2015 increase. 2020 could see 2.0C over 1880, and that’s game over for humanity.

David – you’re probably right, but I did read another article (which I’ll endeavor to find) that did a great job of describing the effect that axis tilt might have on climate change. It was fascinating. I’m still not sold that these carbon credits aren’t just a way for the people to be milked a little more. Trudeau strikes me as a kumbaya kind of guy, not bright enough or inclined enough to do his own research, but happy to follow what’s “trendy”. Not like his father, who was far more skeptical, a deeper thinker.

Methane is going to be the real killer, 20 times worse than CO2. The permafrost up north – look out!

Over-population, shortage of clean water, CO2, methane, Fukushima – could we have done any better job of fuc*ing up the planet?

B.W.E., I agree with you on Carbon Tax, although “revenue neutral” for the rich and middle class, it will just dump costs on the poor. I too greatly fear the methane.

The Milankovitch theory of ice age cycles has been accepted as a fact for at least a quarter of a century, and probably longer. Only the finer details remain to be worked out.

Human changes in the atmosphere are another subject altogether, IMO. There is an outside chance your library still has a copy of Isaac Asimov’s book Fact and Fancy – my local libraries have been dumping his materials for quite a while. A 1959 essay titled “No More Ice Ages?” was the first glimmer I had of climate change. As Asimov said, the human CO2 contributions to the atmosphere were bound to completely overwhelm the delicate doings of the Earth’s positioning as described by Milankovitch. But in 1959 man-caused climate change was not considered interesting except for such exotic things as squelching ice ages. We’ve learned a lot since then, and have totally ignored that knowledge. That’s why things are becoming so desperate.

The Eemian Interglacial ended in a Super-Interglacial of elevated CO2 and temps, followed by a crash to Ice Age in about ten years, cause unknown. Our present Interglacial has entered Super-Interglacial conditions similar to Eemian at the same time(+12,000yrs) as the Eemian, and we do know the cause: fossil fuel burning by humans. No natural mechanism can explain the crash to Ice Age, so may I suggest a human mechanism? Imagine an Eemian human technological civilization, that caused a Super-Interglacial by fossil fuel burning, then destroyed itself in a nuclear war that produced nuclear winter triggering an Ice Age.

I didn’t know the glacial periods had names, but then that’s not something I’ve ever studied. Regarding the “Eemian”, none of my search finds suggested anything odd about it. Example

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Charles_Turner6/publication/27711152_The_Eemian_interglacial_in_the_North_European_Plain_and_adjacent_areas/links/544ee6050cf2bca5ce90c00e.pdf

As for the ten-years business, that sounds a whole lot like something out of “The Day After Tomorrow”, which on a scale of 1-10 was for me a “1”.

Z.S., your link describes the late-Eemian SuperInterglacial I mentioned(sea level rise leading to linking the Baltic and Arctic). “The ten year business” is not something I made up, but is the opinion of some, but not all scientists(“gradualism” being an older and largely arbitrary assumption). “The ten year business” comes from the latest research. As for the rest of my comment, I understand it sounds like a H.P. Lovecraft story, and I do not expect anyone to believe it. Topic for further reading: the current Glacial/Interglacial Cycle pattern began approx.1.7 million years ago, which correlates to the appearance of Homo Erectus in evolution(there is an opinion that H. Erectus and H. Sapiens are one species). Yes, more Lovecraft, but an entertaining line of speculation that does conform to Occam’s Razor.

“The ten year business” comes from the latest research.

I tried several searches last night, and it didn’t come up in any of them. Still, I’m a perfect novice regarding glaciers, and I’d welcome a link to this “latest research”.

Z.S., my apologies I cannot provide a link. I read a lot and note salient facts in order to gain a general understanding, all I can say is I did not make it up. I will say that investigating the Glacial/Interglacial Cycle, and Hunan Evolution by way of the internet is murky and confusing, I am glad I began my study in the late 1980’s using “books”, that gave me a good view of “the forest”, the internet is(perhaps purposefully?) a confusing display of “the trees”.

Torn on climate change? You need to check out robertscribbler.com.

“The great thing about science is that, whether you believe it or not, it’s still true.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

So-called “climate change” is just another elitist and government scheme for plunder and power. If that were not true, revenue from the the proposed “carbon tax” would be offset by lowering other taxes.

“History informs that government, being nothing but a criminal syndicate of theft and violence can only produce 4 things: poverty, misery, death, and lies.”

An American citizen, not US subject.

A “Carbon Tax” scheme is “revenue neutral”. That is government revenue from a carbon tax is offset 100% by lowering income tax. I shouldn’t have to be telling you this IISIS, since it is spelled out in the article, but as IISIS is an automated FartLand Institute troll, using software that scans the net for articles on global warming, and is very busy auto posting dozens of prewritten comments……..

Interesting. I read the Fartland piece and thought I detected some form of robotics. Thanks.

The positive results in British Columbia appear to be real validation of the idea of carbon tax over cap and trade.

Revenue neutral?

Lower corporate income tax for companies = energy tax on working and poor ordinary folks. The initial tax is just the camels nose under the tent. The tax will increase as well as the introduction of other taxes to change human behaviour. We will be discouraged from driving our own cars and traveling out of town. Get out of your home and into a new ‘sustainable’ 800 square foot apartment. All apartments will be ‘smart’ where your energy use as well as other behaviours monitored 24/7.

And there will be no discernible change in our “one hundred million year” weather cycles. But your freedom will be history.

Propaganda works though.

Agreed. The Climate Change used to be called Global Warming and in the 70s Government claimed we were on the way to another Ice Age. No evidence it is man made. Just indirection and implication.

None other than Psuedo intellectual Leonard Nimoy predicted Ice Age below:

https://youtu.be/1kGB5MMIAVA

The tax will be another funnel out of the middle class to global elites. And we won’t see one benefit…ever.

“Bill Nye”, your opinion that global warming is a hoax is 100% wrong. Your opinion on the Carbon Tax is nearly 100% correct. It will be “revenue neutral” for the middle class, business, and the rich; but the poor will bear all the costs, which like “residential rent” will increase yearly.

Cap and trade has been tried in several places. My impression is that it is an idea that has never worked.

A sales tax on carbon content might be better. That would definitely confront the major pollution from the beef industry.

A balanced budget would also help by pinching off funds for endless war and destruction of democracies by Canadian extraction industries.