Exclusive: Official Washington’s neocons hope they will finally get their wish to bomb Syria’s government, but the crisis of the Mideast – made worse by drastic climate change – won’t be solved by more war, explains Jonathan Marshall.

By Jonathan Marshall

While Washington decision-makers debate whether to launch U.S. military strikes against the government of President Bashar al-Assad, as if Syria suffers from a shortage of war and foreign intervention, the United States continues to ignore underlying issues that have helped trigger recent conflicts in the Middle East and threaten to create much bigger upheavals in decades to come.

Taking the long view, our number one enemy should not be Assad, or even ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, but climate change. Predictions by climate scientists that the Middle East will become nearly uninhabitable by the end of the century — barring decisive global action to curb carbon pollution — put all current conflicts into much-needed perspective.

Experts have been warning for years about the social and political implications of environmental stresses. Consider these cautionary words from the International Institute for Sustainable Development in 2009:

“Already the Middle East as a whole is the world’s most dependent region on wheat imports. . . . If climate change begins to reduce agricultural yields at the same time as international food prices rise, . . . food insecurity, both perceived and real, will increase. . . This, in turn, could alter the economic and strategic balance in every country in the region . . . As Canadian security analyst and journalist Gwynne Dyer notes, ‘Eating regularly is a non-negotiable activity, and countries that cannot feed their people are unlikely to be ‘reasonable’ about it.’”

One year later, a “perfect storm” made that warning come true. Record rainfall cut the wheat harvest in Canada — the world’s second largest wheat exporter — by almost a quarter. Severe drought and wildfires wiped out nearly 40 percent of Russia’s potential wheat harvest. Extreme weather in late 2010 also devastated crops in the United States and Argentina. A once-in-a-century drought led China, usually the world’s largest wheat producer, to begin buying up grain on the international market.

Spreading Chaos

As a result, global wheat prices doubled from the summer of 2010 to February 2011, reaching an all-time high. The spike hit the Middle East — home to the world’s nine top per capita wheat importers — like a plague of locusts. Protesters in Tunisia, the birthplace of the “Arab Spring,” waved baguettes to signal their anger over food prices.

Similar demonstrations struck Yemen and Jordan. In Egypt, where 40 percent of personal income is spent on food, and bread accounts for a third of the typical consumer’s calories, the food crisis fed popular discontent that spilled over into mass anti-government demonstrations on Tahrir Square that spring.

In Africa’s impoverished Sahel, drought and desertification drove hundreds of thousands of desperate migrants to Libya in recent years. The clash between indigenous Arabs and sub-Saharan black Africans helped trigger the uprising against Muammar Gaddafi. His opponents fueled the revolt by accusing black immigrants of taking jobs and becoming mercenaries to keep Gaddafi in power. As a result, Western-backed rebels brutally abused and slaughtered thousands of darker-skinned migrants.

In Syria, the worst four-year drought in its history drove hundreds of thousands of hungry families off their farms from 2006 to 2010. The mass migration overwhelmed the Assad government, which was already stressed by foreign economic sanctions and a huge influx of refugees from the U.S.-led war in Iraq. The tinder was laid for a revolt sparked by internal dissent, fanned by the regime’s overreactions, and stoked by foreign intervention [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Exploiting Global Warming for Geo-Politics.”]

Four years ago, the United Nations predicted that Egypt could become water scarce by 2025, in part due to population growth and upstream diversions of water from the Nile. Climate change has accelerated the timetable.

According to recent reports, “Drinking water shortages have left parts of Egypt going thirsty for up to two weeks in the run-up to Ramadan, with popular frustration over the failure of authorities to tackle the crisis spilling onto the streets. . . The water shortages have exacerbated an already difficult Ramadan in Egypt which saw food prices increase by 12.7 percent in April compared to the same month last year . . . The cost of rice, an Egyptian staple, has more than doubled compared to last year’s Ramadan.”

Pummeling Iraq

Climate change is battering war-torn Iraq as well. As three experts warned in Foreign Affairs magazine last year, “The Tigris-Euphrates river basin, which feeds Syria and Iraq, is rapidly drying up. This vast area already struggles to support at least ten million conflict-displaced people. And things could soon get worse; Iraq is reaching a crisis point. . . In Karbala, Iraq, farmers are in despair and are reportedly considering abandoning their land. In Baghdad, the poorest neighborhoods rely on the Red Cross for drinking water.”

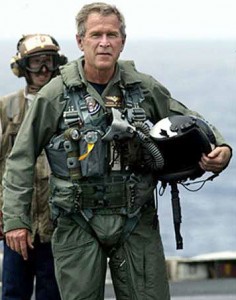

President George W. Bush in a flight suit after landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln to give his “Mission Accomplished” speech about the Iraq War.

Further south, Iraq’s famous marshes are drying up. What a recent report on NBC News called “a catastrophe in the making for one of the world’s most important wetlands,” is evolving into a human emergency. Besides wiping out the livelihood of herders and fishermen, it has contributed to a sharp rise in the frequency and intensity of sand and dust storms, extending deep into Iran and Kuwait. Many inhabitants report severe respiratory problems as a result.

Competition over fresh water supplies is aggravating conflicts within the region. Turkey, which lies upstream from Syria and Iraq, has radically reduced water flows to those neighbors since 1975 to serve its urban and farm needs and is building new dams to take even more, in the face of international protests and even threats of military action from its neighbors.

Meanwhile, in Iraq, the Kurdish regional government has threatened to withhold irrigation water as part of its power struggle with Baghdad. And ISIS, which controls major dams in the country, last year put farmers in four predominantly Shiite Iraqi provinces at risk by cutting flows down the Euphrates River.

The social, economic, and political challenges to the region of coping with heat, drought and related ills are certain to grow. As one climate scientist at Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory said recently, “The Mediterranean is one of the areas that is unanimously projected [in climate models] as going to dry in the future [due to man-made climate change].”

The World Bank estimated last month that future water shortages could slash the region’s GDP by 14 percent by the middle of this century unless countries in the Middle East undertake major investments and radically improve their water management practices to cope with drought. Such dry statistics likely portend further political upheavals, civil wars, and refugee migrations.

As President Obama said in 2014, “If you look at world history, whenever people are desperate, when people start lacking food, when people are not able to take make a living or take care of their families, that’s when ideologies arise that are dangerous.” Scientific studies prove him right.

More War Is Not an Answer

If we take his common-sense insight seriously, then sending more anti-tank rockets to insurgent rebels and bombing a continuously shifting array of opponents from Iraq to Yemen is unlikely to provide lasting solutions for the region. Washington should instead be providing technical assistance, aid to strengthen critical infrastructure, and encouragement for regional collaboration.

Saudi King Salman bids farewell to President Barack Obama at Erga Palace after a state visit to Saudi Arabia on Jan. 27, 2015. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

As two researchers at the Center for American Progress declared in 2013, “Given the shape of these challenges, a new approach is necessary. The United States, its allies, and the global community must de-emphasize traditional notions of hard security more suited to the Cold War, and should focus on more appropriate concepts such as human security, livelihood protection, and sustainable development.”

That lesson, of course, will apply increasingly around the world as droughts imperil food and power production, as rising sea levels swamp island nations and coastal cities, and as increasing heat spreads disease vectors.

If the United States want to act like an “indispensable” nation, it’s time for Washington to demonstrate greater leadership on combating climate change and helping other nations cope with the enormous stress it brings.

Jonathan Marshall is author or co-author of five books on international affairs, including The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War and the International Drug Traffic (Stanford University Press, 2012). Some of his previous articles for Consortiumnews were “Risky Blowback from Russian Sanctions”; “The US Hand in the Syrian Mess”; “Hidden Origins of Syria’s Civil War”; and “Israel Covets Golan’s Water and Now Oil.”]

Climate will do what climate will do, as it has for hundreds of millions of years. Meanwhile, policy needs to be based on hard fact.

There are some cucial, verifiable facts – with citations – abot human-generated carbon dioxide and its effect on global warming people need to know and understand at

hseneker.blogspot.com

The discussion is too long to poat here but is a quick and easy read. I recommend following the links in the citations; some of them are very educational.

What rubbish you are spreading here. Your climate denial claptrap is doing a great disservice to humanity and our planet home. Open your mind, your eyes and your heart, runaway climate change has probably already started and survival of consciousness is at risk. If those who currently are leading us into this mess are not replaced (forcefully if necessary) the displaced hungry millions displaced by crop failures etc will lead to unbelievable conflict world wide and humanity will shoot the hills clear of animals, fish the seas empty and the survivors will turn on each other like feral cats. Time for action is very short indeed. Come together in your communities and demand the wars cease immediately and the efforts of the military industrial complex be redirected from being a death industry to one trying to solve the huge problems we face. If we do not do this God help us and our children and grandchildren

The entity that calls itself “hseneker” is not a real person and has posted an identical comment months ago on another article. These “Fartland Institute” trolls use a type of “Megaphone” software that scans the web for “climate change” articles then swarm the comments. The entity “hseneker” is automated and will not respond. “Lolita” was another troll that did respond but has disappeared after I stomped “her” too many times.

In fairness to the poor dummy, he or she & and all the other deluded deniers aren’t doing a fraction of the damage as Obama, Hillary, the GOP, and the rest. Obama just loves to run his mouth about climate change, but is still doing less than nothing about it.

First a preface, Pres. George Bush was not the pilot when that two seat Navy aircraft made a carrier landing, Bush was merely a passenger. On the subject, this article is very important but needs to be expanded to the global scale, as The Emerging Climate Disaster is worldwide. Rising food prices are affecting everyone, I have noticed the price of two cuts of beef doubling since 2013. An 8kg. bag of rice that was $10 is now 6.8kg for $17. Many food items see multiple 10% jumps over a year. The rate of climate change is accelerating, the 2012-2016 change has been vastly greater than the 2000-2011 change(2000 was the first year of visible effects). In Toronto, we no longer have winter, and right now the heat is like Houston Texas in the 1960’s(the media posts false temperatures typically 10-20C(18-36F) LOWER than actual). The El Nino did not bring its usual rains to California, which is now in permnament drought, meaning the effects of global warming blotted out the El Nino effects. In the recent SE Texas floods, thunderstorm tops reached 70,000 feet(in the recent past 30,000 feet took aircraft over any weather). 2016, at minimum will be 1.2C over 1880’s(IF we go into LA Nina, Dec-May was 1.38C, and the model that has 100% accuracy says back to El Nino in Oct.). So “best case” has the planet at 1.5C by Jan.2020, but we could be there in 2018. Remember, 1.5C is “Game Over”. The American Propertied Class knows all this, although they hide it from us. They have always been “Planners”. Only a chump would believe their plan is to “Be Nice”.

Jonathan Marshall, thank you for this very helpful and progressive report!

True, above. but it is all very good for the military / industrialists, just having filled their order books around the 29 missile bases in Europe, on-going in the middle east and an expansion of sales in S E Asia as the US does its “pivot into Asia” program.

Now that’s the name of the game when added to the US (perceived) exceptionalism and uncontrollable hegemonic ambitions.

The combination is WW III, about the end of 2017, regardless of who occupies the White House. Just a puppet on an Israeli string.

The world domination dreamed of by Mammon’s high priests in Wall Street and the neocon philosophers in Washington looks like it will be another Pyrrhic victory characterized by a devastated world. For those of us who find our golden years are not all that great there is the consolation we will be out of here before the ultimate catastrophe. Ours is probably the luckiest generation ever despite many problems – the Great Depression, a hot world war followed by a long, needless cold war and many regional wars – and we have failed to leave the world in better shape than when we enjoyed it. Not only is ours the luckiest generation, it is probably also one of the most apathetic and pathetic ever.

Bill, I like you wish our generation could have done more to bring about a more peaceful world in our time. At least, if for nothing better, we seem to want to leave this world better off than how we found it. I worry more now in my sixties than I did in my thirties. I look at my grandchildren, and sincerely hope that war will be avoided, and that our environment will sustain itself somehow. Now, not to judge anyone, because I’m not here on earth to do that, but what may be said of a 69 year old grandmother of two who seems to be at the heart of every major controversial theater of conflict that the world has to offer, is our business and not a judgement call. Rather than for me to go on anymore I am leaving a link to just one of the many articles explaining what Hillary is up to these days, and her recent pass. Oh, and does she represent our whole generation? No, because your here, and me too.

http://www.globalresearch.ca/hillary-clinton-destroy-syria-for-israel-the-best-way-to-help-israel/5515741

Thank you for the very interesting link, Joe. Another reason why I’ll most likely be voting “none of the above.”

Bob, re NOTA, I think constructive pause is beyond our collective ken. More’s the pity.

“Think it’s time to STOP children what’s that sound everybody look what’s going down…”

I attended international climate change conferences in Geneva, Rio, and Berlin between 1989 and 1995. I was a powerless assistant to a Japanese civic group. At one point, I had the opportunity to sit down in a small group with a State Department functionary and tell him that I thought the problem is really serious and my country should take serious action. My impression then and now is that he looked at me with arrogant contempt. Anyway, he was wrong, 21 years ago and now. He probably knows it now, but it is a little too late. State Department = Catastrophic Fail.

To think that so many “lawmakers” in the USA do not even accept that man-made climate change is a factor at all, let alone a vital and determining one. War and violence are the only answers our leaders find for their treatment of disagreements with other parts of the world when genuine negotiations and real action need to be taken before it is too late. Bombing is not the way to go.

There must be 51, if not 5100, State Department employees that agree with the analysis and prescriptions of this article. They should write their own dissent memo and make sure the Washington Post and NPR either publish the memo or are shamed for not publishing it.

This is exactly why the Sanders campaign has this right: the hotbed in Syria is due to climate change and pushing more war in this region makes no sense. In fact, de-escalating war is what is needed to get the world on one page with our biggest threat. Coordinating efforts to put carbon as our number one enemy, dooming us all, is what our US agenda needs to be. Wake Up Americans on this, before it is too late.

de-escalating war…sign me up!

Exactly, Priscilla,

Full commitment to education instead of war leads to a gently declining population and ecological agriculture.

How many low-watt bulbs does it take to save the pollution of one bombing attack?

I picture there is a plan to stretch a metaphorical chain link fence all around the Shia Crescent, and make it one big killing field. To provide reference for this I point to the Yinon Plan, and there is of course the Colonel Raplh Peters plan, which is very similar. Increasing ownership of natural resources, while decreasing the excess starving population, I’m sure shows good on a profit and loss sheet. It’s all about the soon to be Tubman’s, and that’s a shame to say that, since Harriet was a great person in her own right, but it’s about the money. We made our oceans into sewage drains, and turned our land into asphalt radiators, and for this we call ourselfs an advanced species. Study any animal you like, maybe your dog or kitten, then tell me who is the advanced one. We should examine the deer, now there is an animal who has learned to adapt to our crazy thing called development. I just don’t know how they do it.

“Such dry statistics likely portend further political upheavals, civil wars, and refugee migrations.” Which, in turn, further aggravates and accelerates climate change – which, in turn, causes more upheavals and wars – which, in turn, further aggravates and accelerates climate change – and on, and on, and on ad infinitum, ad nauseum, ad absurdum.

So let’s go bomb Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, Russia, and everyone else so we can quickly get this show over with and leave the planet for some more intelligent form of life.