Muhammad Ali was a complex and imperfect hero who reflected the turbulence of his time, a reality lost in some eulogies after his death but that playwright Stephen Orlov recalls from a night with Ali 46 years ago.

By Stephen Orlov

There will never be another like him. And, in 1970, I had the good fortune of sharing a memorable night with the Champ, the greatest sports figure in modern history, at the height of his boxing prowess and controversial career.

Muhammad Ali was then out on bail for dodging the draft. He had been stripped of his heavyweight title, banishing him from the ring, and he needed money for his legal fees. The Champ was touring college campuses across America, lecturing mostly white students about his Muslim faith and the sins of racism at home and war abroad.

I was president of the Junior Class at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, and Ali was my top choice for our annual class speaker that March of 1970. From the moment I had first watched the young cocky boxer on the Ed Sullivan Show, skipping rope and brashly spouting in rhyme poetic victory predictions about his upcoming match, he became my sports idol.

His charisma on and off the ring was captivating. Ali’s stand against racism and the Vietnam War later inspired my activism as a leader of the anti-war strike at Colby, provoked six weeks after his visit to our campus by the National Guard shootings of students at Kent State.

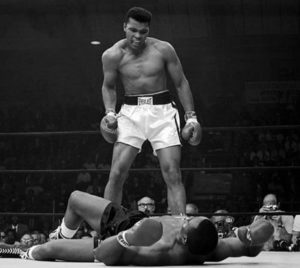

Ali first claimed the heavyweight title with his shocking technical knockout of Sonny Liston in 1964, the same year Dylan released his protest anthem, The Times They Are a-Changin’, and 15 months after, he beat Liston again in nearby Lewiston. By the time Ali came to Colby five years later, a tidal wave of counter-cultural rebellion had engulfed the country, empowering the great social movements of the day — civil rights and black power, anti-war and feminism; Native and Gay rights; the United Farm Workers’ boycott and Earth-Day environmentalism.

The college gym was packed that night, and a crowd of students, professors and town folks who couldn’t get a seat stood outside weathering the cold to hear his talk on outdoor loudspeakers set up for the event. The only problem was I couldn’t find Ali.

The Champ didn’t like flying, so I had been informed by his booking agent, who charged a thousand dollars for the speaking engagement, that Ali would arrive by car at the local Holiday Inn three hours before the evening speech. I went to the hotel, which had lit on its huge neon sign “Welcome Muhammad Ali!”

Thirty minutes ticked off my watch, then 45; finally an hour later, I called the only other hotel in town and sure enough the Champ had just arrived with his entourage of fellow Black Muslim men and women packed into two limousines. I rushed over and met Ali, just as he and his companions were sitting down for a meal at two large round tables.

Star-Struck

I must admit I was star-struck sitting across from my larger-than-life hero, barely muttering a few words to “Mr. Ali,” as we dined over a huge meal he ordered for all. When we finished eating, Ali stood up as the hotel manager came over with the bill and said proudly, “I can’t thank you enough for dining at our hotel. It’s been a great honor to serve you.”

The Champ replied with a gracious smile, “It’s been my pleasure,” and promptly walked out without paying the bill. As we departed, I glanced back at the dumbfounded manager, bill in hand, frozen on his spot.

When we arrived at the gym, the crowd was buzzing with anticipation. I knew exactly how I would introduce Ali. I began with a few rarely-quoted lines from Abraham Lincoln’s 1858 Senatorial debate speech in Charleston, Illinois, expressing emphatically that he never believed in equality between the white and black races, and then I simply added, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Muhammad Ali.”

The Champ rose to a rousing ovation and pulled out a speech from his suit pocket, which he never looked at during his hour-long oration, peppered with improvised commentary decrying white racism and preaching the Black Muslim cause.

When I stood up to chair the Q&A, I felt tiny next to the towering 6’3” Champ. After a half hour, with great trepidation I took the liberty of posing the last question. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, based on Alex Haley’s interviews with the dynamic Nation of Islam minister who allegedly had been assassinated on orders of its founder Elijah Muhammad, had a formative impact on my life, and I was determined to ask Ali what he thought of those murder allegations against his leader.

He turned toward me with a scowl and denounced white honky “this and that,” scolding me and the racist media for making such spurious charges. He said, “I loved Malcolm like a brother but he was wrong to turn against our esteemed spiritual leader.” I wasn’t exactly shaking in my boots, but I kept my eye on his clenched right fist.

The 20 or so Black students enrolled at Colby had requested front-row seats. Two weeks earlier, they had occupied the college’s chapel in protest, demanding more affirmative-action policies and the hiring of a Black professor to teach African-American History.

When Ali finished his speech, he agreed to meet with them in a private room. I accompanied the group and sat down among them, until I realized their prolonged silence signaled I didn’t belong. I left without saying a word and waited outside to say goodbye to the Champ.

Hero But No Saint

When they came out a few of the Black male students were visibly upset watching Ali embrace with warm hugs a few of their Black female classmates enamored with the Champ. Ali hopped into his limo and off he went without spending the night.

I never learned any details about their private chat with Ali, but when I later asked one of the more militant of those students how it went, he merely shrugged his shoulder, leaving the impression that it wasn’t quite what he had expected.

Ali went on to claim the heavyweight title a record three times and became a legend in and out of the ring. The man risked years of imprisonment for his beliefs and his principles, sacrificing his championship crown, the most glamorous in all of sports back then, and millions of dollars that came with it; a far cry from so many sports “heroes” today, who’d rather peddle their trademark shoes than comment on the pressing social issues of our day.

The young boxer who threw his Olympic Gold Medal into the river as a personal sign of protest against racism in his country became the greatest sports ambassador in American history. He was the most recognizable person on the planet, a champion of peace, justice and respect for the disabled, inspiring millions across the globe. Like all iconic activists, he provoked society to change toward his call.

Ali was not a saint; he was a complex hero, a product of turbulent times who dared put his career and his freedom on the line to challenge the powerbrokers of his day. Over the years, as his body and his voice deteriorated from Parkinson’s, his social activism continued, marked by a generosity of spirit that spoke eloquently to our humanity. And now in death, his legacy will live on, spanning generations to come.

I’ll never forget my night with Ali, my brief encounter with the greatest of our time.

Stephen Orlov is an award-winning playwright. His allegorical-comedy play, “Freeze,” has just been published by Guernica Press. And his comedy-drama, “Sperm Count,” will be published this September by Playwright Canada Press in a ground-breaking anthology, Double Exposure: Plays of the Jewish and Palestinian Diasporas, which he has co-edited with Palestinian playwright, Samah Sabawi.

Nice article. For another perspective, Brian Becker shares some of his recollections of Ali at: https://www.spreaker.com/user/radiosputnik/muhammad-ali-dont-let-them-bury-his-real and also at: https://www.liberationnews.org/muhammad-ali-hostage-release-trip-iraq-media-wrong/