The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 blasted apart the country’s political structure and left behind widespread chaos, but Iraqis may be slowly digging out of the wreckage, says ex-CIA official Graham E. Fuller.

By Graham E. Fuller

Iraqi politics are in turmoil — nothing new here. Not surprisingly, the post-invasion order is taking a long time to shake down, given the destruction of the old. Entirely new relationships had to be forged under the new, radically changed environment.

What Iraq requires above all is the painful creation of a new sense of national identity and unity. That poses demands on both Shi’a and Sunni. Ironically, much of the Shi’ite — and even Sunni — religious establishment seem to be closer to a national vision than politicians who are pursuing narrow party agendas.

The Shi’a have not handled the post-Saddam situation well. As the numerical majority, the Shi’a quickly moved to ensure their electoral dominance over the political order after Saddam Hussein and have sidelined the once-ruling Sunnis from a major voice in governance. Worse, Shi’ite militias have behaved harshly against Sunni communities in an effort to reduce Sunni power and even to avenge the past. This very Shi’ite heavy-handedness is one reason why some Iraqi Sunnis have lent support to the “Islamic State” (ISIS, or Da’ish) with its militantly anti-Shi’ite policies.

This anti-Sunni bias of two successive Shi’ite administrations is both unacceptable and damaging to the country. Regrettably, it is also understandable — partially. After centuries-long exclusion from any meaningful role in Sunni-dominated Iraq and suffering oppression at the hands of the Sunni state, the Shi’a seized the moment after the fall of Saddam to ensure that their newly-won power via elections could never again be taken away from them.

Their fear was real: large segments of the Sunni population have viewed recent Shi’ite rule in Baghdad — the seat of great Sunni power for long centuries — as somehow something illegitimate, perhaps even transient. Saudi Arabia refused to even recognize the new Iraqi government for six years (even though Riyadh also hated Saddam) because it perceived the new Shi’ite-dominated Iraq as some kind of an artificial creation propped up by Iran.

That view has to change. The Sunnis of the region, and particularly Iraqi Sunnis, are going to have to suck up the new reality and acknowledge that yes, this is a major geopolitical turning point in the traditional sectarian balance of power in the Gulf. But Iraq is still Iraq, and once it stabilizes, it will play a new, albeit more complex role in the region.

And to the extent that this new reality becomes accepted in the region, the grounds for Iraqi Shi’a paranoia and the sidelining of Sunnis in governance should diminish.

A Big Thing

This is a big thing — we’re talking about the very identity of the new Iraq — historically Sunni in the regional power equation. But now its Shi’ite element is strong. So what is it then that defines an Iraqi — or a Shi’ite? After all, like all human beings, Shi’a possess more identities than simply being Shi’a all day long.

When sectarian identity in Iraq has been a matter of life or death, or the denied Shi’a political or economic well-being over long periods, of course the sectarian identity has dominated. As things calm, however, other facets of identity will emerge.

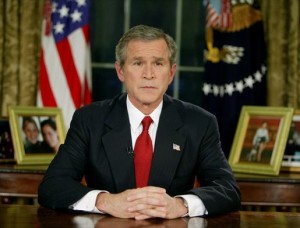

The U.S. military’s “shock and awe” bombing of Baghdad at the start of the Iraq War, as broadcast on CNN.

Shi’a themselves are diverse. They come from different regions of the country. Some are secular while some are religious, some are conservative, others are liberal or socialist, some are rich, some are poor, some are businessmen, some are laborers. Some favor Iran, some don’t. And personality clashes among them abound.

Sooner or later these multiple diversities should make up the natural stuff of Iraqi domestic politics like anywhere else. Sunni businessmen or bankers or socialists or engineers or farmers can make common cause with their Shi’ite counterparts — out of common interest. But we are not quite there yet.

Lately some interesting things have been happening. First, there have been strong demands from many Iraqis, and especially within the Shi’ite community itself, for a government of technocrats to replace the often incompetent and corrupt politicians currently in power.

Politicians can never be kept out of politics, but a more balanced and competent technocratic government would go a long way towards restoring confidence among many Iraqis, and especially among the Sunnis. And, if Shi’ite politicians think about it, they will want their voices to predominate over a united Iraq, not a partitioned Iraq. So they’ve got to run the country for the benefit of all Iraqis, or there will be no united Iraq to preside over. The country could even split apart.

Second, some key elements of the Shi’ite clergy are often more enlightened that their political counterparts. The impassioned young cleric, Muqtada al-Sadr, bane of the U.S. occupation, is back yet again. Often mercurial, he also has a huge loyal following including a militia; his power and reputation rest particularly upon the impeccable clerical and nationalist credentials of his famed clerical father and uncle — both murdered by Saddam.

More to the point though, Muqtada has regularly demonstrated streaks of broader Iraqi nationalism even within his sectarian power base. He has spoken for all of Iraq against the U.S. occupation; he believes in a united Iraq and not just a Shi’ite Iraq. Lately he has made remarks critical of Iran, a country that has often offered him refuge in the past and has supported him with funding and weapons.

But Muqtada is his own man, and he is making it clear that Iraq, while grateful to Iran for all its help over the years, cannot let Iran run Iraq; Iraq must be independent and sovereign.

This development was in the cards. Indeed, in my book with Rend Rahim Francke (The Arab Shi’a, 2001), we underscored, even before Saddam fell, the latent tensions between Iran and Iraq. One country is Arab, the other is Persian; even their Shi’ite cultures demonstrate different colorations.

Iraq is historically the center of global Shi’ism, not Iran. Ayatollah ‘Ali al-Sistani in Iraq is the most important Shi’ite cleric in the world who has long spoken in the name of Iraq, not in the name of Shi’ite power.

And over the longer run Arab Shi’ia in the Gulf are more likely to look to Arab Iraq for support rather than to Iran. The two countries are destined to be rivals in the Gulf in the future; indeed the outlines of some of that rivalry are beginning to make themselves evident. Interestingly, the once very large Sunni Muslim Brotherhood, for the time being in momentary eclipse, also has a national Iraqi view more than a Sunni one.

An American soldier carries a wounded Iraqi child to a treatment facility in March 2007. (Photo credit: Lance Cpl. James F. Cline III)

What kind of a leadership role in the region will Iraq’s complex new mixed Shi’ite/Sunni character play? It will have to be an Iraqi outlook, and not a sectarian outlook. In the past Sunni-led Iraq played a powerful role in the pan-Arab nationalist movement. Even today Iraqi Shi’a will not cease being Arab. But where will their natural allies in the Arab world lie?

It’s still going to take a while for Iraq to shake down. ISIS alone is a deep source of conflict and instability. Worse, Saudi Arabia’s militant anti-Shi’ite campaign is highly destabilizing across the region. The Kurds are still negotiating their place in a new Iraq while Turkish foreign policies have now grown erratic. Syria is utterly unresolved. All these conflicts raging around Iraq make it hard for any country to settle down to stable politics.

Based on several of these straws in the wind though, Iraq may slowly be coming to acknowledge the lose-lose character of its present sectarian politics. Sadly, many of it political leaders are in it for themselves as much as for sectarian ideology.

But the Shi’a’s existential fears may now be slowly ebbing, especially if ISIS is defeated. And Iran itself may realize the need to tread cautiously in Iraq lest they lose major influence in a backlash against them.

Graham E. Fuller is a former senior CIA official, author of numerous books on the Muslim World; his latest book is Breaking Faith: A novel of espionage and an American’s crisis of conscience in Pakistan. (Amazon, Kindle) grahamefuller.com

You forget that the sunnis and kurds had more power then you and others suggest. They had and still have presidential posts, different ministerposts even though their % shouldnt have given them those positions,, so to say that they were mistreated isnt true, fact is since Saddam was overthrown, the sunnis supported terrorism in Iraq, (Al Qaidah and then Daesh) from 2003 bombings raged in shia areas, this lead to the shias giving back and it was the shia scholars like Sistani that stopped massacres on sunnis.

I didn’t know Shi’ites wanted Nouri-al-Maliki’s government replaced with technocrats. I knew the dictator was hated among Sunnis, but I thought he was liked by his own Shi’ites. He must have been a divisive figure. Nor did I think they wanted the current technocrats out due to their incompetence and corruption. They must be divisive too!