Exclusive: Under growing economic and political pressure, the new Saudi leadership is showing a dangerous impulse toward military interventions, raising prospects for a direct and destructive confrontation with its regional rival Iran, writes Daniel Lazare.

By Daniel Lazare

Now that Saudi Arabia has severed diplomatic ties with Iran and reportedly bombed Iran’s embassy in Yemen, the big question is whether the Saudis are desperate and unhinged enough to launch an attack across the Persian Gulf. While Saudi leaders insist they have no such intent, there are mounting pressures pushing them in that direction.

The ruling family is under unprecedented strain. Its economy is shrinking; it’s bogged down in a seemingly endless war in Yemen; and its human-rights policies are an international scandal. If countries could have nervous breakdowns, Saudi Arabia would be well on its way. And when breakdowns occur, nations do crazy things.

King Salman the President and First Lady to a reception room at Erga Palace during a state visit to Saudi Arabia on Jan. 27, 2015. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Of course, there is always the possibility that sanity will suddenly descend upon the Saudis. But reason seems to be in increasingly short supply. Here’s a quick rundown of the reasons why Saudi Arabia is in such dire straits that war with Iran might appear to Saudi leaders as the best remaining option.

Reason #1: Economic collapse.

The 70-percent crash in oil prices since mid-2014 is not unprecedented. Crude plunged some 70 percent during and after the 2008 financial crisis, though it quickly bounced back once central bankers began cutting interest rates. But this time around the realization is growing that the prices will not be coming back anytime soon.

The reason is simple: a classic crisis of over-production straight out of Das Kapital as shale drillers grow more adept, sidelined producers such as Iran go on-stream, and demand continues to slide due to the collapse of the Chinese economy and ongoing listlessness in Japan and the West. Too many goods are chasing too few customers, a problem affecting not just energy but raw materials in general.

As The New York Times recently warned: “The commodities hangover, the dark side of a decade-long boom, could last for a while.”

This doesn’t bode well for Saudi Arabia. When a country’s fortunes are bound up with a single commodity the way the Saudis’ are with oil, the result is not just a business reversal, but an existential crisis. Leaders wind up discredited, while government as a whole enters into a crisis of legitimacy.

Saudi Arabia would be in better straits if it had used its income to diversify. But faced with a gusher of oil wealth seemingly without end, the Saudis preferred to spend rather than invest. By 2013, they were more dependent on oil revenue than 40 years earlier.

Thus, the kingdom’s choices are severely limited. The military card is one of the few left in the deck.

Reason #2: The United States.

U.S.-Saudi relations nearly collapsed after the attack on the World Trade Center in September 2001, but thanks to a compliant Congress and a supine press, President George W. Bush was able to cover up evidence of high-level Saudi complicity and put the alliance back on track. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “The Secret Saudi Ties to Terrorism.”]

But things were never the same. Bush’s invasion of Iraq upset the delicate balance in the Persian Gulf by tossing out Saddam Hussein, a Sunni, and replacing him with a series of pro-Shi‘ite governments increasingly beholden to Iran.

Obama worked hard at repairing the damage. But his decision to withdraw support from Egyptian dictator Husni Mubarak in the middle of the Arab Spring left the Al Saud wondering whether he would toss them overboard when the going got rough. Obama’s demand that Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, an Alawite (a variant of Shia Islam) and a Saudi bête noire, “must go” pleased the Saudis, who joined with the Qataris and other “friends of Syria” to contribute $100 million to anti-Assad rebels.

But the Saudis were taken aback when the White House began complaining that the money was going to ferocious Sunni Islamists whose atrocities against Shi‘ites, Christians and other religious minorities wound up driving the population into the arms of Assad’s secular Baathist government.

A similar pattern followed the Saudi decision to send troops across the 16-mile King Fahd Causeway to crush democratic protests in Shi‘ite-majority Bahrain. When Obama ventured a few words of mild criticism, the Saudis made no effort to hide their annoyance.

Then, when the U.S. entered into nuclear talks with Iran, the Saudis expressed alarm that the Americans might be switching sides. Feeling alone and abandoned, they concluded that they had no choice but to act on their own when Shi‘ite Houthi rebels seemed to be at the point of gaining control of Yemen. Fed up with White House dilly-dallying, the Saudis launched an air war against the Houthis after giving the U.S. only an hour’s notice.

The more the White House resisted being drawn into the Saudis’ paranoid worldview, the more mistrustful the Saudis became and the more aggressive their behavior grew, a pattern that would repeat itself in the months ahead.

Reason #3: The logic of sectarianism.

From a Western perspective, the Sunni-Shi‘ite conflict makes no sense. In the final analysis, a war of succession among Muhammad’s followers that has raged on and off since the Seventh Century, it is as if the heirs of the Merovingians and Carolingians were still blasting away at one another in the rubble of Brussels. But where few Westerners can even remember who the Merovingians and Carolingians were or which one came first, Muslims behave as if their civil war occurred just yesterday.

The explanation is actually rather simple. As the self-appointed “custodian of the two holy mosques,” i.e. Mecca and Medina, the Saudi royal family bases its claim on Muslim law, the notion that its rule is legally valid according to shari‘a and that it is therefore incumbent upon all Muslims to accede to its legitimacy.

But Shi‘ites view the Saudis as merely another pack of illegal Sunni usurpers with zero legitimacy. For the Saudis, this is no laughing matter. The more insecure the regime grows, the more it sees such slights as fighting words.

When you’re a theocracy, in other words, fine points like these are all-important. This is why the 1979 Iranian revolution filled the Saudis with such dread; it was the first time Shi‘ites had taken state power in centuries. It is why the Arab Spring protests that nearly toppled the Sunni ruling family in neighboring Bahrain were equally as frightful.

If Bahrain’s 70-percent Shi‘ite majority had succeeded, it would have brought Shi‘ite state power to within a few miles of Saudi shores. From there, it would have been a hop, skip and jump to Saudi Arabia’s oil-rich Eastern Province where the local Shi‘ite majority is equally unhappy with Sunni rule.

All too aware that Shi‘ites outnumber Sunnis nearly two to one in the nations bordering on the Persian Gulf, the Saudis feel increasingly isolated on their own home turf. Their only option, they believe, is to gather Sunni forces from afar and use them to counter the Shi‘ite threat at home.

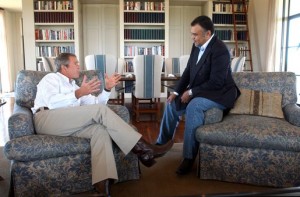

Prince Bandar bin Sultan, then Saudi ambassador to the United States, meeting with President George W. Bush in Crawford, Texas, on Aug. 27, 2002. (White House photo)

As Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan once told Sir Richard Dearlove, head of the British intelligence service MI6, “The time is not far off in the Middle East, Richard, when it will be literally ‘God help the Shia.’ More than a billion Sunnis have simply had enough of them.”

The war against Shi‘ite Alawites in Syria, Shi‘ite protesters in Bahrain, Shi‘ite Houthis in Yemen, and Shi‘ite dissidents like Sheik Nimr al-Nimr in the Saudis’ own Eastern Province could be just a prelude to the real war against the center of Shi‘ite power in Iran.

Reason #4: Implementation Day.

Like Israel, Saudi Arabia was overjoyed when the United Nations Security Council imposed trade sanctions on Iran in 2006 for refusing to suspend its uranium enrichment program. Not only did the measures isolate Iran politically and economically, but it had the added benefit of cutting off a fellow oil exporter from the markets, thereby helping to insure that prices would remain high for years to come.

But with sanctions about to expire in the wake of last year’s nuclear accord “implementation day” could be just days away all those emotions are now running in reverse.

Ironically, sanctions were not entirely negative for Iran. While the Saudis succumbed to the lure of easy money, Iran facing a shutdown of exports didn’t fall into the trap of total dependency on oil production. Instead, Iran had no choice but to build up other sectors.

As Foreign Affairs points out, Iran’s economy is highly diversified as a consequence, with oil and gas accounting for less than a fifth of GDP. At roughly $17,000, per-capita GDP is ahead of China and Brazil. With some 4.4 million young people enrolled in universities, 60 percent of them women and 44 percent majoring in the so-called STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and math, Iran is clearly an emerging powerhouse.

So Iran is far less vulnerable to the ups and downs of the energy markets, which means its relative weight within the region will likely grow. The Saudis can practically feel the ground moving beneath their feet as the economic center of gravity shifts to the other side of the gulf.

The Saudis do have one advantage. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, their military expenditures exceed Iran’s by as much as seven to one. Although Iran would almost certainly prevail in a drawn-out war of attrition since it has nine times as much active and reserve military personnel, the Saudis might believe that could deal a harsh blow to their rivals by deploying high-tech air power and that Iran’s ability to retaliate would be limited. After all, as sectors of the ruling family are probably asking themselves, why spend billions on a high-tech offensive capability if you don’t use it?”

Reason #5: Islamic State.

Saudi attitudes toward the Islamic State (also known as ISIS, ISIL and Daesh) are ambivalent. While vowing undying enmity toward these extremists, the Saudis are aware that the group enjoys significant popular support among the region’s Sunnis.

When Karen Elliott House, former publisher of The Wall Street Journal, visited Saudi Arabia in November 2014, she encountered a “Saudi imam [who] told me that his son is begging to go to Syria to join ISIS. While the imam says he is discouraging the teenager, he acknowledged that he finds the ISIS call for a caliphate ‘exciting.’ Like all too many Saudis, he sees the Al Saud as too worldly.”

For those repelled by Saudi royal greed and corruption and what member of the Saudi rank-and-file is not? ISIS is thus the logical alternative. Frederic Wehrey, a scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, makes a similar point.

“Sunni clerics,” he notes, “have always said, ‘Well, ISIS is kind of bad, but at least ISIS is standing up to the Shias in Iran.’”

This puts the Saudis in the hotspot since not only are they fighting against ISIS, but they are also allied with the U.S., which, from a Sunni perspective, now appears to be tilting toward Iran. That makes the Saudis doubly uncomfortable.

The only way the ruling family can redeem itself in the eyes of the Wahhabist ulema (as the mullahs are collectively known) is by escalating its own war against Shia Islam. This is why the Saudis have wound down participation in the U.S.-led effort against ISIS in Syria and Iraq in order to concentrate on the war in Yemen. The Saudi monarchy wishes to see ISIS beaten because it represents an eventual threat to the kingdom. But the mullahs are more comfortable fighting against Shi‘ism, and the royal family has no choice but to go along.

Reason #6: Internal Saudi dynamics.

The Al Saud are not only isolated internationally, but domestically. The late king Abdullah was a mild modernizer who encouraged young people to study abroad and built the King Abdullah University for Science and Technology, located in Thuwal on the Red Sea coast, as a center for co-education. His successor, the 80-year-old Salman bin Abdulaziz, is the opposite, a hardliner who doubled public executions after acceding to the throne last January, stepped up aid to Al Nusra, the Syrian branch of Al Qaeda, and then launched the air assault on Yemen.

Where Abdullah was a skilled consensus builder, Salman, a member of the so-called Sudairi Seven, a powerful faction within the royal family, apparently sees no need to work as hard at building support and is hence comparatively isolated.

For Saudi watchers, the results are evident from Salman’s appointments. He sidelined one crown prince after gaining the throne, put his nephew in his place, and then handed real power over to his favorite son, Muhammad bin Salman, who, at just 29 or 30, is now minister of defense, deputy crown prince, chief of the royal court, and chairman of the council for economic and development affairs.

The results have been disastrous. Brash, inexperienced, and ill-informed, Muhammad did not study abroad very unusual for scions of the Saudi elite but instead gained a bachelor’s degree from King Fahd University in Riyadh, a snake pit of racism, backbiting, and petty tyranny if confidential employee reviews are to be believed (“they cheat, steal your benefits, trap you, and have no respect for employees third circle of hell”).

A recent interview with The Economist was positively eerie. Over the course of five hours, the young prince insisted that everything in the kingdom was fine, that popular support for the royal family was firm, that the war in Yemen was going swimmingly, and so on.

When asked why, at 18 percent, the female labor participation rate is among the lowest in the world, he insisted that it has nothing to do with the fact that women can’t drive or can’t leave home without a male chaperone. Rather, it is the fault of the women themselves.

Muhammad said of the typical Saudi woman: “She’s not used to working. She needs more time to accustom herself to the idea of work. A large percentage of Saudi women are used to the fact of staying at home. They’re not used to being working women. It just takes time.”

Thanks to Muhammad’s efforts to strengthen his position in the line of success, the German spy agency BND complained in a report last month that “the careful diplomatic stance of older members of the Saudi royal family has been replaced by an impulsive policy of intervention” in Yemen, Syria and elsewhere and that the Al Saud were “prepared to take unprecedented military, financial and political risks to avoid falling behind in regional politics” meaning that more dangerous interventions were likely to follow.

Instead of less war, in other words, the outlook is for more. For the moment, Muhammad is a popular figure. Poets and singers write songs about him, and friends depict him in various social media as a macho warrior surrounded by lions and fighter jets.

But that could change in a flash as gas taxes are raised and other revenue-raising measures kick in. In 2011, the regime was only able to save itself during the Arab Spring by spending $130 billion to pump up salaries, build housing, finance religious organizations, and otherwise buy social peace. But austerity means an unwinding of social benefits that could bring political discord back to the table. So the Al Saud have every reason to be nervous.

Bottom line: As the family business craters, the U.S. winds down its military commitments, sectarianism intensifies, and ISIS and Iran both grow more threatening, the House of Saud may see no choice but to mount a swift assault across the gulf.

As Muhammad bin Salman told The Economist, a Saudi-Iranian war would be “a major catastrophe.” But with its own catastrophic collapse looming, the kingdom may lash out at its prime enemy first.

Daniel Lazare is the author of several books including The Frozen Republic: How the Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy (Harcourt Brace).

Former Wall Street Journal reporter Ron Suskind found out as much in a meeting with a senior adviser to Bush. Recalling the incident in the Oct. 17, 2004, issue of The New York Times magazine, Suskind wrote:

“The aide said that guys like me were ‘in what we call the reality-based community,’ which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.’ I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore,’ he continued. ‘We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality – judiciously, as you will – we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors … and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.’â€

In effect, the neocons are saying to their duped supporters and anyone else foolish enough to listen: Don’t worry about the reckless spending, the bloody wars, the imperial overreach and the mounting burden on Americans. It’s all part of the plan. We create history. We create reality. And we can create a new historical reality where none of that matters.

Neoconservatism and Zionism

Neoconservatism is a political movement born in the United States during the 1960s. Neoconservatives peaked in influence during the presidency of George W. Bush, when they played a major role in promoting and planning the invasion of Iraq that left the country completely destroyed and divided. Neoconservatives frequently advocate the “assertive†promotion of democracy and promotion of “American national interest†in international affairs including by means of military force. Most neocons share unwavering support for Israel, which they see as crucial to US military sufficiency.

Zionism is a nationalist and political movement of Jews that supports the establishment of a “Jewish homeland†in the territory defined as the “historic Land of Israelâ€. Since the majority of Jews were not Zionists until after WWII, Zionists used an array of misleading strategies, including secret collaboration with the Nazis and false flag terrorist attacks, to push immigration. This growing violence culminated in Israel’s ruthless 1947-49 “War of Independence,â€in which at least 750,000 Palestinian men, women, and children were expelled from their homes by Israeli forces. This massive humanitarian disaster is known as ‘The Catastrophe,’ al Nakba in Arabic. In 1975, the General Assembly defined Zionism as a form of racism or racial discrimination. Today, over 7,000 Palestinian men, women, and children are imprisoned in Israeli jails under physically abusive conditions (many have not even been charged with a crime) and the basic human rights of all Palestinians under Israeli rule are routinely violated.

Chris Moore – The Politics of ‘Creative Destruction’

The author makes one big mistake. The Houthis are not Shiite. They are Zaidi Sunnis which is very close to the majority Sunnis than Shias. I mean they are not Wahabi Sunnis. More than 90% of the population of Yemen stands with them. Iran too, supports them. Iran supports Sunni Palestine and Sunni Syria as Well. The Saudi propaganda insists that the Houthis are Shiite because they are supported by Iran. Nonsense. The war on Yemen is because of the Houthis drive for independence from the dominating Saudi influence in Yemen. Nothing more.

Zaidi is cosidered Shia. The first sect of Shia, historically, was Zaidi.

Zaidi is cosidered Shia. The first sect of Shia, historically, was Zaidi.

The Arabian desert, Hejaz, never had a significant role in the civilization and governance and rules over Muslim population, except the Arabic language , turned out to a holy language by emergence of Quran ( literary it means “ recitationâ€). By commercial production of paper in late 8 century ( needed for the new emerging states), the oral Quran, was written down as a Book and spread as the holy book of Muslim . Arabic language roots was linked to the unaccessible Hejaz desert, but the language was flourished and developed in fertile lands of Sham ( Syria) and Mesopotamia ( Iraq). Figh ( Islamic jurisprudence) and rule of governance developed in fertile lands however the roots was attributed to the remote deserts.

Mixing up religion, history, Suni, Shia, etc, with the mundane petty politics of Aramco, neocones, and Al-Sauad family is a lack of knowledge of history, religion, military strategy and oil politics.

It is very easy to understand from available data that 95% of Saudi regime revenue comes from oil, the other 5% comes from pilgrimage. Development of transportation in last century made faster and easier travel and boost the pilgrimage industry and easy money for Saudi. All over the history the pilgrimage revenue was not enough to maintain a sustainable government organization in the holy cities let alone the vast desert. The desert never had had any other role in Islamic civilization except the holistic sanction of so called the Book.

Every one know that the imperialistic need for oil has bestowed a rule to Al-Suade family in 20 century. To close eyes and adhere the problems to Sunni and Shia is a grave mistake.

Answering th the question : Will Saudi attack Iran or no? Does not need a theoretical analysis, neither a historical, nor religion. The first and most important aspect of posing such question brings up a military question and its possibility. Such attack is less dependent to Saudi family courage, stigmata, arsenal, personnels, skill, trainings, but depends more to 6 USA air craft carriers patrolling Persian gulf, air bases in Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, and other depots and bases in Arabian peninsular plus an air craft carrier from France present in the Persian gulf.

A weak military adventure is doomed, and will be a disaster to the initiator.

Recent event in Persian gulf, kneeling down, symbolically, of 10 American marines for 6 Iranian solders, does not have any military significance but it shows that political environment is not ripe for attacking Iran.

Any wars comes in different stages. There is no suicide war, but the last stage of war is “total warâ€. Suadi Arabia is not capable of creating a total war. It does not have any potential to launch a total war. Any other type of war, at the present situation, will be distinguished by world powers. Wahabi ideological manipulation can generate disposable soldiers ( suicide bomber) but not a total war.

I’d imagine the US would want to have a totally “hands-off” situation if war erupts. A Navy site tells about where the carriers are, and at the moment only one is in the mideast.

http://www.gonavy.jp/CVLocation.html

An attack on Iran would probably include Israel, either in the open or under wraps. Paint some of the airplanes in Saudi colors, and be careful to keep them out of range of Iranian missiles.

Mr. Lazarus’ endless clichés, false assumptions and hackneyed expressions are quite irritating.

To begin with, who ever said that the Chinese economy was collapsing, or that the stock market crash there spelled any such thing? This is not 1929. No economist today seriously argues that stock markets could have a determining effect on the rest of the economy.

I understand the gist of what he is trying to say, and sympthaize, but a writer should do his homework before writing. And a writer need not have a doctorate under his sleeve for that, just some willingness to inform him- or herself about basic facts, whichever side of the fence or however concerned one happens to be about present dangers. The idea is to avoid repeating the same inanities of the corporate media.

For example, he writes: “From a Western perspective, the Sunni-Shi‘ite conflict makes no sense. In the final analysis, a war of succession among Muhammad’s followers that has raged on and off since the Seventh Century, it is as if the heirs of the Merovingians and Carolingians were still blasting away at one another in the rubble of Brussels.”

First of all, I have no idea how he is able to translate events in the seventh century A.D. into what is nothing more than Wahhabi-sponsored barbarism, one that no one countenances except meatheads in Western capitals. Being a scholar in Islamic Studies, I just don’t get it.

Second, the Merovingians and Carolingians of western European history were never part of any “civilization” that covering the globe, as the multireligious, technologically and culturally superior Islamic civilization was that laid the foundations for every branch of modern science, conceived the idea of the modern book and mass books on an unprecedented scale, reinvented paper (originally a Chinese pastime) and mass produced it for that purpose, and on and on.

The Merovingians and Carolingians were employed as the defenders of a moribund Roman Church (called “Western Church” by historians) that gradually separated from the main body of Christendom to carve out its own little wonderland in whatever remained of the Roman Empire’s western provinces. The Merovingians and Carolingians pillaged and murdered people who were more firmly attached to their Germanic roots, wherever they found them.

If there is one conflict that has lasted into modern times from that time it is the Franco-German one. The rest is a long history that we have not even begun to leave behind us, despite two world wars costing nearly a hundred million lives and a Western society that has collapsed at least twice (not counting the 1840s).

To be blunt, the idea of a Sunni-Shi’a war is a recent fabrication dating from the years just before the collapse of the British and French empires.

Even the worst Ottoman Sultan, Abdülhamid, who flirted with a new fashion of pan-Islamism then, cared about little more than maintaining his decadent rule in the latter half of the 19th century. In fact, it was a delegation of concerned Muslim subjects of the Isma’ili Shi’a branch of Islam who tried to persuade the Ottoman rulers to re-establish the Sunni-conceived Caliphate. The Caliphate had been suspended for a long time but not yet abolished. The Sultanate was a temporary institution devised in the interest of keeping order in the sprawling Islamic world.

Anyway, regarding any “Sunni-Shi’a” conflict, Mr. Lazarus should understand, if he has not yet, that it takes two to tango. Saudi Arabia and its emirate minions are the prime source of sectarianism in the region and worldwide. They finance and operate so-called Islamic centers, international youth organization, mosques, etc., literally on every continent–including Latin America.

In a word, Wahhabi sectarianism is a foreign and domestic policy arm for rabid, imbecilic regimes originally installed from outside by the British, and continuously egged on by the United States, both of whom are selling countless billions worth of arms to them.

This article shows a near-total lack of knowledge of any of this.

Sorry for misspelling your name as “Lazarus.” I meant “Lazare.”

Thank you, Mr. Shaker. As you point out, “the idea of a Sunni-Shi’a war is a recent fabrication dating from the years just before the collapse of the British and French empires”. Another recent fabrication is the Zionist movement.

The Zionist movement is a recent fabrication?! Would you care explain, please.

Numbers doesn’t matter. There are more rats living on this planet than human 6 to 1 ratio. If Saudis are sunni and they afraid because like any scared degenerate, low life scum would be and they know no sunni will come to their rescue.

Zionism is not about religion or having a land to call you own and live on it peacefully with your own kind, sing a song and practice your faith like Amish people do.. It’s about power and control. In order to unite all Jews around the world to combine their strength against everyone else in terms of Money, Information, Tactics, Ownership, etc…….and make the rest of the people goyim to their wishes.

Another recent fabrication is the Zionist movement.

how for fabrication, sir?

fabrication

— the action or process of manufacturing or inventing something

— a product of fabrication; especially: a lie, a falsehood

Throughout eastern Europe in the late 19th century, numerous grassroots groups were promoting the national resettlement of the Jews in what was termed their “ancestral homeland”, as well as the revitalization and cultivation of the Hebrew language. These groups were collectively called the “Lovers of Zion” and were seen to encounter a growing Jewish movement toward assimilation.

A religious term of great importance, Zion (Jerusalem), was considered appropriate for the secular Jewish political movement to adopt at the turn of the 20th century.

The first use of the term “Zionism” is attributed to the Austrian Nathan Birnbaum, founder of a nationalist Jewish students’ movement Kadimah. Birnbaum used the term in 1890 in his journal Selbstemanzipation (Self Emancipation).

Zionism was established with the political goal of creating a Jewish state in order to create a nation where Jews could be the majority, rather than the minority they were in a variety of nations in the diaspora.

Different geographic and political definitions for the “Land of Israel” later developed among competing Zionist ideologies during their nationalist struggle.

Though later Zionist leaders hoped to create a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael, Theodor Herzl “approached Great Britain about possible Jewish settlement in that country’s East African colonies.” Another area considered was part of the “unoccupied” territory in Argentina.

The Zionist program saw little success until the British acceptance of “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” in the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Zionism increasingly sought to leverage “The Great Game”, the strategic economic and political rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia. In the post-Second World War post-colonial period, the Great Game has continued in the New World Order machinations of the Great Powers and regional powers as they vie for geopolitical power and influence in the area, especially in Afghanistan and Iran.

Heterodoxy

Copernicus’s theory that the earth revolved around the sun was arrant Heterodoxy at a time when the earth was thought to be the center of the universe.

AKA – – Revisionism or iConoclasm… .

Iconoclasm

http://www.timesofisrael.com/golda-and-ben-gurion-the-action-figures/

Zionism is a nationalist and political movement of Jews that supports the establishment of a “Jewish homeland†in the territory defined as the “historic Land of Israelâ€. Since the majority of Jews were not Zionists until after WWII, Zionists used an array of misleading strategies, including secret collaboration with the Nazis and false flag terrorist attacks, to push immigration. This growing violence culminated in Israel’s ruthless 1947-49 “War of Independence,â€in which at least 750,000 Palestinian men, women, and children were expelled from their homes by Israeli forces. This massive humanitarian disaster is known as ‘The Catastrophe,’ al Nakba in Arabic. In 1975, the General Assembly defined Zionism as a form of racism or racial discrimination. Today, over 7,000 Palestinian men, women, and children are imprisoned in Israeli jails under physically abusive conditions (many have not even been charged with a crime) and the basic human rights of all Palestinians under Israeli rule are routinely violated.

I forgot one little tidbit directly related to the Saudi/Russia relationship.

Recall Bin Doorknob’s meeting with Putin just prior to the 2014 winter Olympics in Russia?

(Paraphrase), “We control the terrorists in your backyard. We can guarantee safety at your games…”

Or not ??

Is this the Saudi version of diplomacy ?

Another great article by Daniel Lazare.

Russia’s Lavrov and his open-mic accident calling the Saudi’s a bunch of ‘retards’ only confirms Russia’s distrust (hatred?) of Saudi Arabia.

An attack on Iran would be the proverbial 3 strikes and you’re out. The first strike is the bogus ‘market share’ oil strategy which has pounded all major oil producing countries (not withstanding its own shot in the foot). The second strike is the ‘state-sponsored’ terrorism in Syria and elsewhere.

A well-measured response against Saudi Arabia from Russia (as not to provoke a US retaliation) is guaranteed if Saudi messes with Iran. Saudi’s massive Ghawar oil field is a sitting duck and one Russian missile would fix Saudi’s wagon.

So if Saudi wants $250 oil, attack away. One problem for them; they won’t be able to participate in the bonanza.

The Muslim population in the world is about 1.6 Billion. Shiahs are only 12-15% of this population. Could someone please explain why are the Sunni Muslims so afraid of such a tiny minority?

Will Mr. Lazarre or Mr. Loeb like to try to answer it?

I do not know where did you get the impression that Sunnis are afraid of the Shia from? The article is about the “Saudi Royal Family being scared of losing its power”. In fact, you can explain the whole US and Saudi Arabia Policy in the Middle East on one point. That point is to make sure that what Happened to the Shah of Iran in 1979 DOES NOT HAPPEN TO THE ROYAL FAMILIES ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE GULF…………..The ONLY other issue that shapes the US foreign policy in the Middle East is ISRAEL thanks to the chock hold the Israel lobby has on the US!!

They are not afraid of them as shias,but shiism which is not Islam is being spread by Iran.

and wahabism is such a proper interpretation of islam!!!!

aand wahabism is the only true and correct interpretation of islam?

Numbers doesn’t matter. There are more rats living on this planet than human 6 to 1 ratio. If Saudis are sunni and they afraid because like any scared degenerate, low life scum would be and they know no sunni will come to their rescue.

Saudi Arabia is presently in economic troubles due to oil prices less than $30 a barrel. It always has been a great vassal of Washington and now that US-Israel relations are in troubled waters Washington is seeking another puppet to carry out its aggression in the Middle East. It fits the stupidity of present neocon foreign policy to expand and solidify US dominance in the world.

Saudi Arabia is presently in economic troubles due to oil prices less than $30 a barrel. It always has been a great vassal of Washington and now that US-Israel relations are in troubled waters Washington is seeking another puppet to carry out its aggression in the Middle East. It fits the stupidity of present neocon foreign policy to expand and solidify US dominance in the world.

A Saudi Iran war might send oil prices back to $100 or more. Could this be a factor pushing the Saudis towards war.?

It is pretty clear that the Saudis executed their Shia cleric and 47 others in order to try to knock the Iran nuclear treaty’s implementation track. It didn’t seem to work, so I am holding my breath as what they will do next to ramp up provocation, hoping for a blow up.

“…what they will do next to ramp up provocation, hoping for a blow up.”

I doubt if that would work. IMO it’s more likely to be a “bolt out of the blue” like Pearl Harbor, or a False Flag attack. Say, a gang of crazy guys from Iran tried to attack one of the Holy Places. The crazy dead guys would of course be loaded with Iranian passports and other convincing documents.

I’m afraid the author of this essay did a good job of spooking me. The Saudis have dug themselves into a hole, and an attack on Iran would do several things.

1/12/2016 headline from oilprice:

War Between Saudi Arabia And Iran Could Send Oil Prices To $250

They could really do a job on those evil heretics in Iran – a sort of final solution.

Are they up to the job? Looking through some old internet articles suggests the Saudis have been stockpiling the necessary ‘stuff’ for quite a while. They’ve bought an awful lot of stand-off missiles and the airplanes to deliver them.

From the Brits have come many hundred of the fine Storm Shadow cruise missiles. It wouldn’t surprise me a bit if Israel has sold the Saudis as many more stand-off cruise missiles as they want – especially if they’d be used against Iran. The land-based models would be especially convenient.

Israel is mentioned only once, and casually. The Israeli-patriot neocons are adept at stirring up trouble without leaving many fingerprints. Remember how Georgia was encouraged to attack Russia in 2008? Ukraine? Libya? Iraq? Syria? Arranging for Saudi Arabia to get into this mess, then offering up an ‘obvious’ solution would be par for the course for them.

A cynical person could deduce the insane Saudi attacks on Yemen are merely a “warming-up” exercise for the big show. All the pilots would get some practice, and the duds could be weeded out. Everybody gets to play with the new high-tech toys, and the bugs can be combed out. It would become a methodical drill, smashing every known installation, and iran would become another Iraq – just as a Sunni Allah meant for it to be. At this point Israel would have a totally free hand in the entire area – just as the Old Testament Yahweh meant for it to be. With any luck at all, the whole mess would lead to WW3, and the End-Time Protestants would rejoice, for it all worked out just as the New Testament God promised.

THE INSTINCT TO KILL

Daniel Lazare’s article above, “Will Saudis Seek War with

Iran?” provides an excellent and cogent analysis of realities

in Saudi Arabia.

Included should be the role of Israel and Yahweh as Zacharary

Smith’s comment of January 15.

It should be noted that that the role(s) of US and EU involvement

are also casually dealt with by Lazare. By this is meant not only

the policies and ACTIONS of the Obama Administration (weapons

sales etc.) but the political climate in the US and elsewhere.

(no political candidate of either US party provides any reason

for hope. As I have mentioned previously, I find it doubtful the the

US will fulfill its agreements on lifting sanctions to Iran either now or

in the future. The talk on the US campaign trail of the poor helpless

Israeli VICTIMS who must be supported —with money and

weapons no matter what Israeli policies and illegal activities

may be,no matter how many murders of Palestinians, illegal

construction of settlements, and Israeli “mowing of Palestinian

lawn” there may be. After all, Israelis love Beethoven.(So do I

but ” equality” Beethoven did not pursue but he was rather

an inheritor of the clearly non-“equal” views of the Free

Masons and similar groups. There is no “Egalite” in the “Liberte,

Egalite, Fraternite” of the French Revolution but more the

special role of the artistocratic artist who alone could

penetrate the cosmos and interpret it. Thereafter came

the rightwing German ideology of the 19th and 20th century

in various forms described in detail elsewhere.

Many thanks to Lazare for his landmark contribution.

—-Peter Loeb, Boston, MA, USA

Zachary Smith, you nailed it. The prospect of $250 a barrel oil, a strong rational driver of behavior that superficially appears driven by ” crazy stuff”.

It is pretty clear that the Saudis executed their Shia cleric and 47 others in order to try to knock the Iran nuclear treaty’s implementation off the track. It didn’t seem to work, so I am holding my breath as what they will do next to ramp up provocation, hoping for a blow up.

From my point of view Islamic Kalif in Iran rest the potential danger for world peace. Republic has no sense for this regime, because existence of Kalif has no mean to Republic.

My reading is “Conflict between the Islamic Califate (Da’esh), not Saudi Arabia, and Iran poses the is primary danger to world peace, but Iran does not recognize Da’esh a danger because the Da’esh “Califate” is an incomprehensible entity to the Islamic Republic of Iran.”.

This makes sense if you recognize that in Islamic usage “Kalif”, meaning “representative”, or “deputy”, references from Mohammed: A Kalif in Islamic usage, is, properly, “A representative of Mohammed”, which means to be a Kalif one would have to represent all Islam, all versions, variants, sects, tribes, persuasions. A Kalif would have to represent basic Islam, the Fundamental Islam Mohammed’s actions and example represented, which was a tolerant, accepting and egalitarian Islam that united people with differing manners, habits, customs, tribal beliefs and backgrounds, and even religious beliefs into a unity whose responsibility was to look after, first, the less fortunate of the ‘family’ and then the family, each and all fellow-members.

As you can see from this, a self-styled “Caliph”, and “Caliphate” who/that attacks fellow Islamic family members and others of other religions not attacking him/it or Islam, and that seeks to beat all Muslims and Islam to fit to the prejudices of his/its sect, cannot be an Islamic Kalif:

How can Mohammed be represented by anyone twisting what Allah assigned Mohammed to present and represent into a puritan’s-pretzel of his own, not Allah’s Mohammed-presented example?

Thus, the Islamic Republic of Iran, which does not call itself a Kalifate, since a Kalifate would have to represent the whole entirety of Islam (with the diversity of Islam today this would be an impossibility) does not recognize the Da’esh ‘Califate’ to be a legitimate, or an actual political entity.

Iran probably does perceive Da’esh an artificial entity, a physically and politically non-existent eruption of sectarian (Wahabi puritanist) fanaticism. These have arisen and succumbed periodically in Islamic history, doing greater or lesser damage in their eruptions, with the basics of fundamental Islam, working as a constant, often as an undercurrent, maintaining, or returning, sometimes eventually, rationality.

I think I would agree with the writer, that the real danger in the present Middle-East situation is the Da’esh entity. It is to a degree formless and mindless, which means it is formed and directed by who feeds it and directs its actions, who may appear to be the Saudis, but who are using the Saudis, pushing the Saudis to the fore-front by flattering them that their Wahabi Islam Sect is ‘True Islam’, to keep them moving (and from reading their own scriptures in broader, Islamic, focus). When the Saudis do eventually reassess their position they will see they are being used. If they do so sooner, and drop away, ceasing to support Da’esh, they will see that Da’esh continues on, being fed and directed by its direct controllers, Israel, which directs the U.S., the U.S., which Israel directs, Europe, who Israel also directs, and Turkey, who is like the little outcast kid who wants to be in the big-kid group, who wants to too much to recognize the big-kids don’t really like or want him, and so who, therefore, use and abuse him, giving him, and helping him behind the scenes to do, things he should know better than to do, the doings of which demean him or are self-destructive, like shooting down an airplane with too little provocation.

Saudi Arabia is in something of the same situation as Turkey, though it has been treated a bit more respectfully. Its being pushed to ‘prove’ itself ‘tough on terror’ led it to stupidly execute Nimr al Nimr for Nimr doing what Mohammed defined a high plane of jihad, struggle to represent and present the fundamental elements of Islam. In pre-Zionist Judaism, which Judeo-Christians are more familiar with, what Nimr was doing, and was executed for would have been acting as a prophet. Executing a religious leader for acting properly as a religious leader, in every religion, is the most fundamental of fundamental errors. It is difficult to imagine how the Saudis could have blundered themselves into an action that stupid. The divine retribution that will inevitably result will be the usual: Loss of religious credibility in the eyes of the believers in the religion. In other words, Saudi Arabia has kind of painted itself out of its corner. As the writer appears to suggest, it is no longer a contender and can be ignored by Iran, who, the writer seems to be saying, should be focusing on the Da’esh danger. I agree.

beautifully written