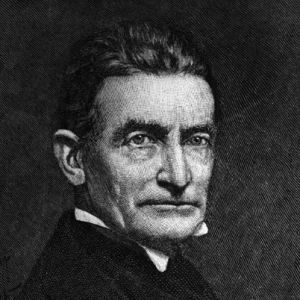

For some American abolitionists, President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of Jan. 1, 1863, was a long time coming, but it was a moment for rejoicing among a racially mixed force in Kansas that included veterans of John Brown’s anti-slavery uprisings, writes William Loren Katz.

By William Loren Katz

Only the skies were gloomy as Emancipation Day 1863 dawned and the First Kansas Colored Volunteers — a mix of African-Americans, Native Americans and Black Indians — assembled at Fort Scott to celebrate President Abraham Lincoln’s long-delayed Emancipation Proclamation.

The men had been fighting the Confederacy since war broke out in 1861. The white officers even longer — as radical abolitionists whom John Brown commanded in his Kansas battles to free slaves in the 1850s (before his failed raid against the armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, which led to his trial for treason and his death by hanging in 1959).

Celebrating Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation issued on Jan. 1, 1863 about 500 people gathered at Fort Scott in eastern Kansas. As flags, sewn by women of color, floated above the fort, people sang the “The Star-Spangled Banner,” then they shared a barbecue and strong liquor. Next, soldiers and officers burst into their song. They honored their “immortal hero” with “the John Brown song.” The soldiers added this line: “John Brown sowed, and the harvesters are we.”

This self-liberated army was commanded by officers whom John Brown had trained and led in a Kansas guerrilla war to end slavery. By the Civil War, the First Kansas Colored Volunteers included the kind of fighters that Brown had dreamed of rallying to the cause. For this multi-racial force, this was the time to complete “the old man’s work.”

The men of color were recruited from 10,000 people from the Seminole, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Cherokee Nations who followed Chief Opothla Yahola on what began as a peace march — to avoid serving the Confederate cause — from the Indian Territory. Attacked three times by Confederate cavalry on their desperate voyage, they finally decided to head for Union lines in Kansas.

By the time they reached Kansas, only 7,000 survived and many decided they were no longer pacifists. As early as October 1862, 225 men of the regiment drove off 500 Confederate troops.

The force continued Brown’s work with forays into Missouri to free slaves, relatives, loved ones and strangers. Their white officers — once hunted by the Federal government as “John Brown traitors” — now were appreciated as experts in guerrilla warfare and were deployed in Kansas, then regarded as a less significant Civil War battle zone. There they and their men transformed the Civil War into a Revolution.

This heroic story is told in Mark A. Lause, Race and Radicalism in the Union Army (University of Illinois Press, 2009) largely ignored since publication.

William Loren Katz is the author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage and 40 other books. His website is http://www.williamlkatz.com

Anyone would have to admire a man noble enough to give his life while standing up for the rights of others — unless maybe a person has no concept or understanding of what it is to be noble. Many of us do this in small ways, John Brown was a Giant.

Wasn’t there a book about white men from the south who tried to reach union lines and were executed by confederate troops? Something approximately like “Lincoln’s Legions”?

The breeding of African slaves as a brutal business model that gives the birds eye views about the kinds people the slave owners were. These controlled Africans were forced to mate and produce new slaves! Refusing to mate on command could mean severe whipping or being lynched for disobeying the master’s orders!

Time and again, one hears about America being a Judeo Christian nation; where were these God fearing Christians at time of slave breading? Did they have any objections witnessing the demoralization humans who were forced to have sex whether they liked it or not?

Even animals in the wild do not practice this kind of stuff. Nowadays, you hear these same Christians castigating African Americans as having no family values or connection! Do these people remember this horrific forced breeding history?

This guy, John Brown, was one of those few white Americans who saw something wrong with slavery and was willing to pay the ultimate prize for what his conscious told him was very wrong.

The breeding of African slaves as a brutal business model that gives the birds eye views about the kinds people the slave owners were. These controlled Africans were forced to mate and produce new slaves! Refusing to mate on command could mean severe whipping or being lynched for disobeying the master’s orders!

Time and again, one hears about America being a Judeo Christian nation; where were these God fearing Christians at time of slave breading? Did they have any objections witnessing the demoralization humans who were forced to have sex whether they liked it or not?

Even animals in the wild do not practice this kind of stuff. Nowadays, you hear these same Christians castigating African Americans as having no family values or connection! Do these people remember this horrific forced breeding history?

This guy, John Brown, was one of those few white Americans who saw something wrong with slavery and was willing to pay the ultimate prize for what his conscious told him was very wrong.

Some people would follow the devil into the pits of hell while believing they’re on the way to creating heaven.

Oops! typo: which led to his trial for treason and his death by hanging in 1959 – 1859?