From the Archive: The past often is prologue — making it especially important to know how a politician built his career and who helped him. In 2000, too little attention was paid to George W. Bush’s personal history and how it might shape his disastrous presidency, a void that Sam Parry tried to fill.

By Sam Parry (Originally published on Aug. 15 and 19, 2000, as Parts 2 and 3 of a series)

At times grudgingly, George W. Bush traced virtually every early step his father took. Like his father, George W. went to both Andover Academy and Yale and joined the secretive Yale fraternity Skull and Bones. Like his father, George W. joined the armed forces. Like his father, George W. benefited from wealthy family connections while starting out on his own.

But the most important similarity between the careers of George W. and his father is the link between oil and politics. Like his father, George W. made his first business investments in West Texas oil ventures in Midland. Like his father, George W. sought to establish his political career by seeking elected office in Texas, where he ran for Congress at an early age.

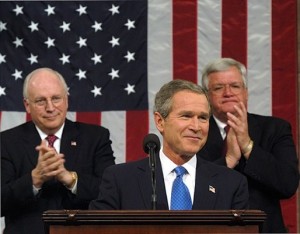

President George W. Bush pauses for applause during his State of the Union Address on Jan. 28, 2003, when he made a fraudulent case for invading Iraq. Seated behind him are Vice President Dick Cheney and House Speaker Dennis Hastert. (White House photo)

While the cadence and direction of his steps match, George W.’s early record seems like a child walking around in his father’s oversized shoes. In school, George W. was a C student, while his father graduated Phi Beta Kappa. In sports, George the father was captain of the Yale baseball team while George the son was captain of the cheerleading squad. In the oil business and politics, too, George W.’s early record was eclipsed by his father’s.

But what George W. may have lacked in accomplishments, he made up for in ambition and charm, two traits that served him well in both oil and politics. In 1978, this ambition led George W. to embrace both family legacies, oil and politics. To some, this decision to pursue both goals at the same time might smack of bravado or even cockiness. But George W. was eager to try.

George W.’s Drive

With practically no political experience of his own, George W. launched an unsuccessful bid for U.S. Congress. He lost badly to the Democratic incumbent. George W. later said that his biggest mistake that year was running a race “he couldn’t win.” The loss still gave George W. a taste of politics he would never lose.

That same year, he incorporated his own oil-drilling venture, Arbusto (Spanish for bush) Energy. Both his race for Congress and his oil business were based in Midland, his father’s old stomping grounds. In fact, George W. opened an office in Midland’s Petroleum Building, the same office building where his father started out more than 25 years before. [See the Washington Post’s profile, “The Turning Point After Coming Up Dry, Financial Resources,” by George Lardner Jr. and Lois Romano, July 30, 1999, and Harper’s Magazine’s “The George W. Bush Success Story: A heartwarming tale about baseball, $1.7 billion, and a lot of swell friends,” by Joe Conason, February 2000.]

While his run for Congress fell short, his oil business venture seemed promising at first. Just as his father had done nearly 30 years prior, George W. Bush sought financial assistance from his uncle, Jonathan Bush, a Wall Street financier. Jonathan Bush pulled together two dozen investors to raise $3 million to help launch Arbusto. Among the investors was Dorothy Bush, George W.’s grandmother. At the same time, Jonathan Bush was lining up investors for Arbusto, he also was raising money for George H.W. Bush’s presidential explorations. Many of the funders were the same. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999]

Unfortunately for George W., 1978 was not the best time to start up an oil-drilling company in West Texas. After a brief price spike in the late 1970s, the price for a barrel of oil dropped throughout the 1980s to less than $10, which in turn sank many small businesses in the West Texas oil industry.

Still, while other oil ventures failed, George W. kept his afloat in the 1980s thanks to family connections and international financiers attempting to build and nurture relationships with his father, who was elected vice president in 1980.

The Lifelines

The first of three major bailouts occurred in 1982. That year, despite the millions already pumped into Arbusto, George W. faced a crisis. His balance sheet read $48,000 in the bank and $400,000 owed to banks and other creditors. George W. realized that he had to raise additional cash. He decided to take Arbusto public. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999.]

With the company so deeply in debt, however, George W. would need a new infusion of money to clear the books. In stepped Philip Uzielli, a New York investor and friend of James Baker III from their Princeton days. According to George W., Uzielli was introduced by George Ohrstrom, one of the original Arbusto investors and Uzielli’s business partner.

Ohrstrom and Uzielli had, three years before in 1979, purchased a building products firm, Leigh Products Inc. by buying all common shares for $25 per share. At the time, Baker was a director of Leigh Products.

Uzielli worked out a deal with George W. to purchase a 10 percent stake in Arbusto for $1 million. The entire company was valued at less than $400,000. In a 1991 interview, Uzielli recalled the investment as a major money loser. “Things were terrible,” he said. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999.]

As bad as Uzielli’s investment turned out, George W. now had enough money to take his company public. Not, however, before he made one more change. In April 1982, perhaps realizing the negative connotation of “bust,” George W. changed the name of his company to Bush Exploration. The name change also may have had something to do with the fact that George W.’s father at the time was the Vice President of the United States. In June, George W. issued a prospectus.

George W. sought $6 million in the public offering, but only managed to raise $1.14 million. The shortfall was due in large part to the waning interest in the oil industry among investors. The price for a barrel of oil was falling and special tax breaks for losses incurred in oil investments had been slashed. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999.]

Within two years, it was clear that Bush Exploration was in trouble again. Michael Conaway, George W.’s chief financial officer, told the Washington Post, “We didn’t find much oil and gas. We weren’t raising any money.” Something had to be done.

In walked bailout number two in the persons of Cincinnati investors, William DeWitt Jr. and Mercer Reynolds III. Heading up an oil exploration company called Spectrum 7, DeWitt and Mercer contacted George W. about a merger with Bush Exploration. For Bush and his struggling company, the decision wasn’t a hard one to make.

In February 1984, George W. agreed to a merger with Spectrum 7 in which Dewitt and Reynolds would each control 20.1 percent and George W. would own 16.3 percent. George W. was named chairman and CEO of Spectrum 7, which brought him an annual salary of $75,000. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

DeWitt, whose father had owned the St. Louis Browns baseball team and later the Cincinnati Reds, would become a useful partner for George W. a few years later when he made his move to pull a group of investors together to buy the Texas Rangers.

Even though the merged companies still failed to make any money, the pieces were finally starting to fall into place for George W. A chief asset was that George W. brought connections and name recognition to the enterprise. Paul Rea, president of Spectrum 7, remembers Bush’s name as a definite “drawing card” for investors. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999.]

With oil prices collapsing in the mid-1980s, however, it became clear that George W.’s name alone would not save the company. In a six-month period in 1986, Spectrum 7 lost $400,000 and owed more than $3 million with no hope of paying those debts off. Once more, the situation was growing desperate. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

In September 1986, George W. was given his third lifeline.

Harken Energy Corp. was a medium-sized, diversified corporation that had been purchased in 1983 by a New York lawyer, Alan Quasha. Quasha seemed interested in acquiring not just an oil company, but the son of the Vice President. Harken agreed to acquire Spectrum 7 in a deal that handed over one share of publicly traded stock for five shares of Spectrum, which at the time were practically worthless. [Washington Post, July 30, 1999.]

George W. Strikes Success

After the acquisition, George W. was named to the Harken board of directors. He was given $600,000 worth of Harken stock options and landed a job as a consultant that paid him $120,000 a year. By any account, this was not bad for an oilman who had never made any money in the oil business and had lost investors fortunes, large and small. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

But Harken’s investment in George W. appreciated. In 1986, the company had acquired the son of a vice president. By 1989, it had in its camp the son of a president. Harken began looking for oil investments in the Middle East where business and family connections also are very important.

In 1989, the government of Bahrain was in the middle of negotiations with Amoco for an agreement to drill for offshore oil. Negotiations were progressing until the Bahrainis suddenly changed direction.

Michael Ameen, who was serving as a State Department consultant assigned to brief Charles Hostler, the newly confirmed U.S. ambassador to Bahrain, put the Bahraini government in touch with Harken Energy. In January 1990, in a decision that shocked oil-industry analysts, Bahrain granted exclusive oil drilling rights to Harken, a company that had never before drilled outside Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma and that had never before drilled offshore. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

In a matter of weeks, the stock of Harken Energy shot up more than 22 percent from $4.50 to $5.50.

While George W. was finally finding some success in the oil business, President George H.W. Bush was experiencing the high point of his presidency. In August 1990, the forces of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein invaded the oil-rich sheikhdom of Kuwait, choosing to settle a simmering border dispute over oil lands by force. President Bush responded with a denunciation of Saddam for violating international law, though Bush himself had ordered the invasion of Panama less than a year earlier to capture Panamanian Gen. Manuel Noriega on drug charges.

Yet, with the Middle East’s vast oil reserves at risk, international law gained new respect as an inviolable principle. President Bush vowed that the Iraqi invasion “will not stand” and dispatched 500,000 U.S. troops as part of an international force to drive Iraqi forces from Kuwait. In the early months of 1991, the United States led first an aerial assault on Iraqi military and civilian targets, followed by a 100-hour land assault that routed the overmatched Iraqi army and restored the Kuwaiti royal family to power. Bush saw his popularity ratings soar above 90 percent among the American people.

Public Face for the Texas Rangers

Back in Texas, George W. was winning acclaim himself as the popular new owner of the Texas Rangers. The beginning of that deal traced back to an idea of George W.’s Spectrum 7 partner, Bill DeWitt, who wanted to make a play for the purchase of the baseball team.

DeWitt understood that he needed a native Texan in his group of investors. George W. fit the bill. George W. also brought with him family connections to the owner of the Rangers, Eddie Chiles. An aging Midland oilman, Chiles’s ties to the Bushes dated back to George W.’s father’s days in the Midland oil business. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

George W., who had never given up his political aspirations, recognized at once the opportunity this would bring. He could establish his name in his own right and do so as part owner of a highly visible organization. What story line could be better for an aspiring politician than to be part of the old American pastime, baseball?

The group of investors was missing only one thing money. To address this need, George W. tapped a Yale fraternity brother, Roland Betts, who brought with him a partner from a film-investment firm, Tom Bernstein. Betts and Bernstein were from New York, which became a problem when Major League Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth insisted on more financial backing from Texas-based investors.

Commissioner Ueberroth, eager to put together a deal for the son of the President, brought in a second investment group headed by Richard Rainwater, who had made much of his fortunes working for the Bass family of Fort Worth. From 1970 to 1986, Rainwater had turned a modest family fortune of nearly $50 million into a stunning $4 billion empire.

Rainwater agreed to join Betts, Bernstein, and George W., who borrowed $600,000 for his share of the $86 million purchase. But Rainwater did not join without imposing a strict limitation on George W.’s role. George W. was granted 2 percent ownership of the Rangers and was named one of two “managing partners.” But George W. would have effectively no say in running the team. He would be the handsome public face. Rainwater and his lieutenant Rusty Rose would be the brains. [Harper’s Magazine, February 2000.]

George W.’s connections to Harken and his investment in the Rangers which had been made possible by his ties to the oil industry soon made him a millionaire. At last, he had a record of accomplishment to point to. George W. finally was ready to make the leap he had been waiting for. In 1994, George W. ran for and won the governorship of Texas.

The Oil Connection

The oil money connections that had served George W. Bush so well in private life would, like his father before him, continue to serve George W. very well in political life. And, like his father before him, George W. would reward his oilmen benefactors once in office.

During his nearly six years in the governor’s mansion, George W. has presided over what widely regarded as the most polluted state in the country. It ranks first in the amount of cancer-causing chemicals pumped annually into the air and water, first in the number of hazardous-waste incinerators, first in the total toxic releases to the environment, and first in carbon dioxide and mercury emissions from industry. [See “The Polluters’ President,” by Ken Silverstein, Sierra Magazine, Nov/Dec 1999.]

The air quality is arguably the darkest blot on Texas’s environmental record. A majority of Texans live in areas that either flunk federal ozone standards or are in danger of flunking, a shocking statistic in a state of nearly 20 million people. Houston, the nation’s oil- and petrochemical-industry headquarters, has been called an ecological disaster zone. Chemical spills slick its coastal waters and its air quality earned the dubious honor of being the most polluted in the country, eclipsing Los Angeles.

Water quality in Texas isn’t any better. More than 4,400 miles of Texas rivers, roughly one-third of Texas’s waterways, don’t meet basic federal standards set for recreational and other uses. They are unswimmable, unfishable, and, for the most part, undrinkable.

Despite this abysmal record, the state has cut water-testing programs to the bare bones. Between 1985 and 1997, the number of stations monitoring for pesticides in Texas waterways fell from 27 to two. The lack of attention given to these problems is further evidenced by the fact that the state of Texas ranks 49th in spending on environmental clean up. [Sierra Magazine, Nov/Dec 1999]

While missing in action on environmental protection, Gov. Bush jumped into the trenches when the oil industry was threatened. In 1999, when international oil prices collapsed, Gov. Bush pushed for and won a $45 million tax break for the state’s oil-and-natural-gas producers. [AP, April 3, 2000]

To get a sense of Gov. Bush’s priorities, it is worth examining an initiative he promoted that he now widely cites as a successful environmental policy reform. In the Texas Clean Air Act of 1971, 828 industrial plants enjoyed a grandfather loophole that allowed them to operate without obtaining a permit. In 1997, Gov. Bush announced a plan to “close the loophole” for these factories. But the plan was strictly voluntary and carried no penalties for industries that didn’t seek a permit.

Such a plan could have been written by the industries themselves. And as it turned out, it was. In confidential memos obtained by the Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition (SEED) under the state’s Freedom of Information Act, it was shown that Gov. Bush’s administration worked closely with the companies as they were crafting the proposal. [Sierra Magazine, Nov/Dec 1999]

Gov. Bush also found appointees who pleased the oil industry when he was filling seats on the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC), the Texas equivalent of the Environmental Protection Agency. His first choice, Barry McBee, came from a Dallas law firm where he served as an oil specialist. McBee was former deputy commissioner at the Texas Department of Agriculture where he led a drive to gut “right to know” laws that protected farmworkers from unannounced aerial pesticide spraying.

Gov. Bush’s second choice, Robert Huston, was even more fondly thought of by the oil industry. Huston came from the industry consulting firm Espey, Huston & Associates, whose clients included Exxon, Chevron and Shell. Another of Gov. Bush’s appointees to the TNRCC was Ralph Marquez, former vice chair of the Texas Chemical Council’s environmental committee and a 30-year veteran of Monsanto. [Sierra Magazine, Nov/Dec 1999]

It is likely that a President George W. Bush would appoint people from this same mold to serve in environmental and industry oversight positions. For one, McBee is regarded as a leading candidate to head the EPA.

As has been widely reported, Bush has expressed a “kinship” with those in the oil industry. Craig McDonald, Director of Texans for Public Justice, a campaign finance group, summed up the bond between Bush and the oil industry this way: “He’s been friendly to that sector, policy-wise, and they’ve been good to him in return. He rewarded them with tax breaks when they cried that they weren’t making enough money.” [AP, April 3, 2000]

This affinity between Bush and the oil industry and how it might affect a potential Bush presidency has raised alarm bells within the environmental community. At a time when scientists warn of the dire environmental consequences caused by global warming, which in turn is caused by burning oil and other fossil fuels at high rates, environmentalists fear that a George W. Bush White House, closely aligned with the oil industry, would ignore these scientific warnings.

Among other controversial energy topics on which Bush sides with the oil industry are suspending 4.3 cents-per-gallon of the federal gasoline tax, a move that could lead to more gasoline use. He also favored opening up Alaska’s Arctic Wilderness to oil drilling. These initiatives would have strong chances of passage with Bush in the White House and Congress under the leadership of Sen. Trent Lott, R-Mississippi., and Rep. Tom DeLay, R-Texas.

George W.’s support for the Alaskan oil ventures is underscored by the men he chose to serve as his Alaska state campaign co-chairmen, Bob Malone and Bill Allen. From 1995-2000, Malone served as president, chief executive and chief operating officer of the Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., a consortium owned by major oil companies active in the North Slope of Alaska.

Alyeska Pipeline manages the 800-mile Alaskan pipeline, which delivers more than 20 percent of America’s domestic oil production. Before joining Alyeska, Malone served as president of BP Amoco’s Pipelines (Alaska) Inc. [See The Public I, Feb. 28, 2000]

The other Bush co-chair in Alaska, Bill Allen, is the chairman of VECO Corp., which was formed to support offshore oil production in Alaska. VECO now has 4,000 employees and has offices in Alaska, Colorado, Washington State, India, Cyprus and Houston.

Big Oil Pumps in Money

In return for George W.’s continued political support, the oil industry has played a prominent role in funding Bush’s two gubernatorial races and his presidential candidacy. Of the $41 million Bush raised in two gubernatorial races, $5.6 million (14 percent) came from the energy and natural resources industries. [AP, April 3, 2000]

The oil and gas industry has extended its support for the Texas governor to his presidential bid, donating 15 times more money to Bush than to his Democratic opponent, Al Gore. As of June 20, Bush had raised $1,463,799 from the oil industry to Gore’s $95,460, according to opensecrets.org [July 26, 2000]. Of the top-ten lifetime contributors to George W.’s political war chests, six either are in the oil business or have ties to it. [See George W. Bush: Top 25 Career Patrons, The Buying of the President 2000, Center for Public Integrity.]

George W.’s chairman of his campaign’s finance committee was Donald Evans. According to The Austin Chronicle, Evans is “perhaps the governor’s closest friend” and has known George W. for three decades since their Midland days together. Evans is also CEO of Tom Brown Inc., an oil and gas company with the bulk of its production in Wyoming. Evans helped pioneer the Pioneers, a group of Bush financial supporters who have each raised at least $100,000.

In 1995, Bush rewarded Evans by appointing him to the University of Texas Board of Regents, one of the most “powerful patronage” jobs in Texas. Evans rose to chairman of the board. With an annual budget of $5.4 billion and more than 76,000 employees, the Texas university system is one of the largest in the country. The Texas University Board of Regents also manages an investment portfolio of more than $14 billion. [The Austin Chronicle, March 17, 2000]

George W., like his father before him, also brought his Texas oil financial connections to Washington to help national Republican fundraising efforts. In May 2000, Ray Hunt, chairman and CEO of Hunt Oil Co., was named finance chairman of the Republican National Committee’s Victory 2000 Committee. Based in Dallas, Hunt Oil is an independent, private company that is among the top dozen independent oil companies in the United States. [Cox News, May 10, 2000]

Richard Kinder and Kenneth Lay, the former and current CEOs of Houston-based Enron Corp., also rank as two of Bush’s top contributors. Both are members of Bush’s Pioneers and have been longstanding financial benefactors behind Bush’s political career. By the end of 1999, funders connected to Enron had contributed $90,000 to the Bush presidential campaign, the fourth largest bundle at the time. [Boston Globe, Oct. 3, 1999]

Enron, a company worth $61.5 billion, is the No. 1 buyer and seller of natural gas and the top wholesale power marketer in the United States. As governor, George W. has embraced energy deregulation, an initiative on which Enron has led the field of competitors.

In 1997, one Enron facility in Pasadena, Texas, released 274,361 pounds of toxic waste. In many states, this would rank as one of the top toxic pollution emitters, but not in Texas, where nearly 262 million pounds of toxic waste were released into the environment in 1997, the most in the country. [EPA TRI data, 1997]

Sam Parry is co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush.

In a TX race, G W lost to Kent Hance. Afterward, Bush determined never to be out religioned again.

Oh Puleeze Oligarchy,”My Pet Goat!”

The best expose of W was “Shrub”, written by Molly Ivins and Lou Dubose prior to his “selection” by a corrupt SCOTUS. Lots of folks knew what a fucking idiot he was long before 2000.