For American taxpayers, the Iraq War is a gift that keeps on taking, with new plans to spend tens of billions of dollars to retrain the Iraqi army whose initial training cost tens of billions before the army collapsed against a few thousand militants, a pricy dilemma cited by ex-U.S. diplomat William R. Polk.

By William R. Polk

Most readers of the media today are too young to have closely followed the slide into the Vietnam War in the early 1960s. We began in 1961 with less than 2,000 “advisers” and even as late as 1965, the estimated cost of the war was going to be only $100 million.

Four years later, the estimate had grown to almost $29 billion. The war ended up costing America three quarters of a trillion dollars and our little band of advisers had grown to half our army. The moral of the story is that even if the price of admission seems cheap staying through the performance can be huge.

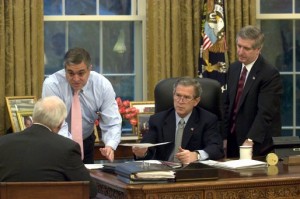

President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney receive an Oval Office briefing from CIA Director George Tenet. Also present is Chief of Staff Andy Card (on right). (White House photo)

So turn to the current venture in Iraq. After we pulled out most of our troops, we spent somewhere between $25 billion and $26 billion to train and equip the Iraqi army. That is roughly $10,000 for each ostensible soldier. So what did we get?

In the first bout of combat, the supposedly best units of the 250,000-man force were routed by less than 5,000 untrained and poorly armed militants. In fact, the debacle was worse than those figures indicate.

First, the 250,000 turns out to include large numbers of “ghosts.” Many “soldiers” existed only as names on official reports. They were the Iraqi equivalent of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls. Gogol’s hero, you will remember, wanted their government records. Even though they were actually dead, they were “officially” alive so on their behalf he could claim their benefits.

Keeping the Iraqis’ names on the organizational charts similarly has enabled senior officers to draw the pay and rations as though the “ghost” soldiers were still manning their posts. No believable audit has so far been made but some observers guess that perhaps as many as a third of the Iraqi soldiers were like Gogol’s “dead souls,” just names.

And, second, many of those who actually did exist were effective only in robbing, raping or killing civilians. That was what “our man in Baghdad” used them for — to terrorize his enemies. Their attitude toward performing against those who could fight back was shown by their preparation for combat.

As an American senior officer reported to Congress, even in relatively safe Baghdad, it was not uncommon for a “soldier” to wear civilian clothes under his uniform. Then, if he got into danger, he could strip off the uniform, pretend to be an ordinary civilian and run away.

I started with a mention of Vietnam. Like the Iraqis, the South Vietnamese officers found ways to make away with our money. Many of them sold their ammunition and even arms to the Viet Minh and exercised great care not to get into “harms way.” We learned, at great pain and huge cost, that if our local ally does not care enough to fight for his homeland, we could not “win” for him.

We all know what the result was in Vietnam. South Vietnam’s half million man army, trained to world-class standards and equipped with the most lethal weapons then known, was defeated time after time by poorly armed bands of guerrillas. Even when backed up by the bulk of the American army and air force, it lost.

So now we are being told that what is needed in Iraq is another $15 billion to $20 billion to once again arm and train the same Iraqi soldiers (and also, as in Vietnam, add some “stiffening” by American “advisers”). The “entry ticket” is now quite a bit more costly than in the early days in Vietnam. What does it amount to?

Fifteen or twenty billion dollars would fund at least 45 new hospitals (a 320-bed hospital in Massachusetts recently cost $300 million) or 200 schools (the national average for a school for a thousand students is about $26 million).

Even such massive projects as the new bridge across the Hudson River in New York is cheap by comparison. For the additional costs of the Iraqi venture, we could have built five of them! And, just as in Vietnam, I predict that the cost of the “performance” will be a multiple of the entry ticket and will stretch out for years.

I don’t begrudge the Iraqis support, but Vietnam taught me two things: first, support is different from replacement and, second, fighting is seldom the answer. The Iraqis must work out their own answer. Then our help might not even be needed..

William R. Polk is a veteran foreign policy consultant, author and professor who taught Middle Eastern studies at Harvard. President John F. Kennedy appointed Polk to the State Department’s Policy Planning Council where he served during the Cuban Missile Crisis. His books include: Violent Politics: Insurgency and Terrorism; Understanding Iraq; Understanding Iran; Personal History: Living in Interesting Times; Distant Thunder: Reflections on the Dangers of Our Times; and Humpty Dumpty: The Fate of Regime Change.

This signifies that while Britons will have the opportunity to learn from previous choices, Australians will

nevertheless be deprived of a complete account of our involvement in Iraq.

Very good points, Mr. Polk. Of course the US does not learn the lessons of history, and history repeats, because the US military and oligarchy does not intend to learn. They no more act in the interest of the US people than the proxy armies. There is no greater congressional concern because they too are servants of oligarchy. To restore order to foreign and domestic policy, democracy must be restored. That cannot be done with the nonviolent tools of the press and elections, because those are now controlled by the oligarchy. Nor can it be done by revolution, although direct action against the corporate media would be a sign of renewal. The US is now itself a disease in its final but enduring sages, an empty suit of armor to be toppled by another oligarchy. Democracy has never been further in the future.