There is a general belief that Americans don’t care much about history, preferring to bask in self-reverential “exceptionalism” with U.S. behavior beyond criticism. But students outside Denver are taking to the streets to protest right-wing efforts to strip dissent from the history curriculum, writes Peter Dreier.

By Peter Dreier

In Colorado, just west of Denver, Jefferson County high school students are protesting their school board’s attempt to rewrite the American history curriculum. In their resistance, they are doing all Americans a favor by reminding us of the importance of dissent and protest in our nation’s history.

The students are reacting to a proposal by the Jefferson County school board — Colorado’s second largest school district with about 85,000 students — to change the way history is taught in the schools.

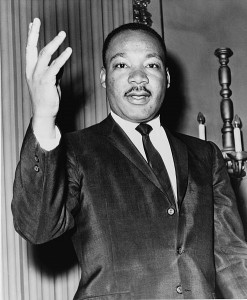

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1964, a powerful example of how dissenters have addressed injustice in America and given meaning to democracy.

Last November, three new board members were elected to the school board, forming a conservative majority. One of them, Julie Williams, has led the charge to revise the Advanced Placement U.S. history curriculum to promote patriotism, respect for authority, and free enterprise and to guard against educational materials that “encourage or condone civil disorder.”

Williams said she believes that the current Advanced Placement curriculum in American history places an excessive emphasis on “race, gender, class, ethnicity, grievance and American-bashing.”

With the support of many teachers and parents, the Colorado students have engaged in a protest of their own to teach the school board a lesson. It began on Monday, Sept. 22, when about 100 students walked out at Evergreen High School, one of 17 high schools in the suburban district outside Denver.

Since then the protests have gained momentum, fueled by social media and student-to-student contact. As the New York Times reported, they “streamed out of school and along busy thoroughfares, waving signs and championing the value of learning about the fractious and tumultuous chapters of American history.”

By last week, the number of students involved in the protest had mushroomed. On Thursday, according to the Denver Post, more than 1,000 students walked out of class behind a new unified slogan — “It’s our history; don’t make it mystery.”

History of Protest

Back in 1900, people were considered impractical idealists, utopian dreamers or dangerous socialists for advocating women’s suffrage, laws protecting the environment and consumers, an end to lynching, the right of workers to form unions, a progressive income tax, a federal minimum wage, old-age insurance, dismantling of Jim Crow laws, the eight-hour workday, and government-subsidized health care. Now we take these ideas for granted. The radical ideas of one generation have become the common sense of the next.

As Americans, we stand on the shoulders of earlier generations of reformers, radicals and idealists who challenged the status quo of their day. They helped change America by organizing movements, pushing for radical reforms, popularizing progressive ideas, and spurring others to action.

To understand American society, we need to know about the accomplishments of people like Jane Addams, Florence Kelly, Eugene Debs, Robert La Follette, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, W.E.B. DuBois, Frances Perkins, Lewis Hine, A.J. Muste, Alice Paul, A. Philip Randolph, Dorothy Day, Eleanor Roosevelt, Langston Hughes, Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss), Fiorello LaGuardia, Myles Horton, Rachel Carson, Walter Reuther, Thurgood Marshall, Bayard Rustin, Woody Guthrie, Cesar Chavez, Barry Commoner, Ella Baker, Jackie Robinson, Bella Abzug, Pete Seeger, Martin Luther King, Harvey Milk, Ralph Nader, Gloria Steinem, John Lewis and Billie Jean King.

If some of these names aren’t quite household names, that reflects our failure as a society to recognize and teach our students about some of the major dissenters, rebels and reformers who have shaped our nation’s history.

Even today, grassroots movements have continued to push and pull America in a positive direction, often against difficult odds. Today’s battles over the minimum wage, Wall Street reform, immigrant rights, climate change, voting rights, gun control, and same-sex marriage build on the foundation of previous generations of dissenters.

Each generation of Americans faces a different set of economic, political, and social conditions. There are no easy formulas for challenging injustice and promoting democracy. But unless we know this history, we will have little understanding of how far we have come, how we got here, and what still needs to change to make America (and the rest of the world) more livable, humane and democratic.

The Jefferson County School Board’s attempt to ignore or downplay the long tradition of dissent, protest and conflict that has always shaped American society is hardly unique. In the early 1990s, Lynne Cheney, who headed the National Endowment for the Humanities during the first Bush Administration (and is the wife of former Vice President Dick Cheney), attacked the teaching of American history for presenting a ”grim and gloomy” account of America’s past.

After that, conservatives on local school boards around the country escalated their efforts and continue them today. It is part of the backlash against the increasing examination by historians of the roles of women, African-Americans, Latinos, native Americans, dissenters, and movements in American history.

But such battles go back even further than Cheney’s campaign. In the 1979 book, America Revised, Frances Fitzgerald examined how the teaching of American history has been the subject of an ongoing debate going back to the 1800s, fueled by political differences over the nature of American identity. Conservatives have traditionally sought to emphasize consensus over conflict in the development of U.S. history textbooks and curriculum.

As the College Board observed in a statement issued on Friday, the Jefferson County students “recognize that the social order can — and sometimes must — be disrupted in the pursuit of liberty and justice. Civil disorder and social strife are at the patriotic heart of American history — from the Boston Tea Party to the American Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement. And these events and ideas are essential within the study of a college-level, AP U.S. History course.”

It would be fitting and appropriate for the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association to give these students an award at their next meetings for their commitment to the teaching of American history. Perhaps one or both of these organizations could invite some of the students to give a presentation about their protest campaign as part of a plenary session on the teaching of AP American history. It would surely be the most well-attended session at either conference.

Such a gesture by one or both of the leading organizations of historians would inspire high school students elsewhere to challenge arbitrary authority and put the two organizations on record in opposition to the efforts by school boards to distort the teaching of history for overtly political purposes.

Peter Dreier is the Dr. E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics, and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department, at Occidental College. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012)

Let’s do it: replace liberal fantasies and myths with conservative ones!

Martin Luther King Jr. – The Beast As Saint http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IShbhepwieA

Larry Krieger, owner and designer of InsiderPrep, and former AP History teacher, is the influence behind Julie Williams in Colorado– who, as she told Breitbart Texas .. the proposal they are trying to pass is to preserve US history from the progressive APUSH and it is similar to actions taken by the Texas SBOE.

“Texas passed its resolution against AP US History. In Colorado, people are talking about that,” she said. “What does it hurt to look into this? Our students deserve to have the best, appropriate education possible,” she added. “Without looking into this, we could be harming our students,” she said. She indicated that over the past year “APUSH and a new fifth grade Sex Ed curriculum were slipped into the schools with little public knowledge.” — which isn’t correct really, On Sept 10, 2014, the Colorado State Board of Education already discussed the issues that came up with the 2014 AP History program, listened to arguments for over 90 minutes and decided it was still acceptable for the State Schools.

So, Texas doesn’t have AP right now. Larry Krieger is the man who talked them into this option. Larry has been doing quite a bit of talking and writing.

News Week

http://www.newsweek.com/whats-driving-conservatives-mad-about-new-history-course-264592

By Krieger’s own admission, there is nothing false or misleading or untrue inside the AP material. The College Board has said over and over that this is a Framework design and as such it negates all of these complaints against the AP History program. So let’s pull some sheets shall we? Let’s look at the orchestrator of these complaints.

Larry Krieger owns InsiderPrep, which is a business that creates and sells books and materials to help a student prep for the AP classes and tests. — Well, it did help up until this year. See, Larry’s Prep course is based on the old study methods, where memorizing is more important than critical thinking. The AP History program has changed drastically, in that it is only a Framework now, not a full course like it was in the past. So, there is no …”series of chronological chapters that match the sequence of topics in the College Board’s official APUSH Course Description booklet.” … Which is how Larry Krieger’s program is developed. No. Now AP is a comprehensive, adaptable Framework.

Quote right off the AP Web site :

A new Curriculum Framework Evidence Planner helps teachers customize the framework by specifying the historical content selected for student focus. It can also be provided to students to track the historical evidence examined for each concept and as review for the AP Exam.

Schools and teachers develop their own curriculum for AP courses. Submitting a syllabus to the AP Course Audit ensures teachers have a thorough understanding of AP U.S. History course requirements and are authorized to teach AP.

— end quote —

See that one line? “Schools and teachers develop their own curriculum…” Meaning that the frame work Can Be fully Right Wing Conservative, going over each of the founding fathers in detail and focusing on the deeds of courageous people…or… it could be middle of the road, focusing on the growth of the nation, or it could be both, or neither.

There are simply too many areas of history to cover them all and importance and values change from state to state and district to district. So, AP created this Framework, stepping away from the static text design and allowing the teachers and districts to create a program suitable for their own use. So this Whole idea that it is missing something is silly. It isn’t missing ANYTHING. If it has a Left or Right or Conservative or Liberal bend, then it was put there by the school, not AP. — Think of it as Object Programming if you know something about that.

Except now there is a problem.. a problem for Larry, anyway. See Larry’s Prep and Study course no long fit the AP History program, because there is no way of telling what the district is going to focus on ahead of time. So there is no Chapter to Chapter.. so basically his Prep courses are useless and no one is going to buy them. So… Larry is out of a job. Apparently he’s not that happy about it either (and I have to admit I wouldn’t be happy myself… but I wouldn’t go around doing what he is doing).

Since Every school, indeed every teacher can create her own syllabi, paying attention to areas and focuses of history which are most in line with the state and local focus– Larry has nothing to sell and his publications are no longer marketable. — Unless he talks you into believing that the new AP Framework design is somehow bad. This is very difficult to do, because there is nothing false, misleading or wrong with the facts or the framework. So, he has to go after something with a lot of emotion behind it, something that will cut through logic and the extra cost of putting together your own AP classes.

Thus begins Larry’s impassioned campaign against AP History, where he takes out bits from the examples of the New AP, twists some things up, reads a little too much into what is not really there — since none of it has to be there, it is all up to the teacher and the school what to build with the Framework — and begins screaming Leftist Democrats!

He screams this over and over, and he finds people like Jane Robbins who is screaming Common Core, and he meets a few people through her who are also working to stop Common Core and he bands up with them, and comes to your Education meeting and tells you all the things every one knows you are not going to like — never telling you that the AP History program can be exactly what you want it to be.

Again.. from the AP History area of the Web Site where you put together your State’s AP Curriculum.

The AP® Program unequivocally supports the principle that each individual school must develop its own curriculum for courses labeled “AP.†Rather than mandating any one curriculum for AP courses, the AP Course Audit instead provides each AP teacher with a set of expectations that college and secondary school faculty nationwide have established for college-level courses.

AP teachers are encouraged to develop or maintain their own curriculum that either includes or exceeds each of these expectations; such courses will be authorized to use the “AP†designation. Credit for the success of AP courses belongs to the individual schools and teachers that create powerful, locally designed AP curricula.

The AP U.S. History course should be designed by your school to provide students with a learning experience equivalent to that of an introductory college course sequence in United States history. Your course should provide students with the analytic skills and factual knowledge necessary to deal critically with the topics and materials in U.S. history.

There are no specific curricular prerequisites for students taking AP U.S. History.

All students who are willing and academically prepared to accept the challenge of a rigorous academic curriculum should be considered for admission to AP courses. The College Board encourages the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP courses for students from ethnic, racial and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in the AP Program. Schools should make every effort to ensure that their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population.

High schools offering this exam must provide the exam administration resources described in the AP Coordinator’s Manual.

http://www.collegeboard.com/html/apcourseaudit/courses/us_history.html

I hope this helps you to avoid all of the confusion and fabricated controversy so that you don’t wind up like Texas.

the truth as usual is between the two extremes. The conservative complaints are legitimate, so are the complaints of the students. your statement

“Back in 1900, people were considered impractical idealists, utopian dreamers or dangerous socialists for advocating women’s suffrage, laws protecting the environment and consumers, an end to lynching, the right of workers to form unions, a progressive income tax, a federal minimum wage, old-age insurance, dismantling of Jim Crow laws, the eight-hour workday, and government-subsidized health care. Now we take these ideas for granted. The radical ideas of one generation have become the common sense of the next.

As Americans, we stand on the shoulders of earlier generations of reformers, radicals and idealists who challenged the status quo of their day. They helped change America by organizing movements, pushing for radical reforms, popularizing progressive ideas, and spurring others to action.”

is correct, but some of the listed people after this included in their agendas things that weren’t so great.

Ms. Erikson, you wrote, “… some of the listed people after this included in their agendas things that weren’t so great.”

Here are those listed people. Please explain which ones you are referring to, and exactly what in their agendas was not “so great”:

Jane Addams, Florence Kelly, Eugene Debs, Robert La Follette, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, W.E.B. DuBois, Frances Perkins, Lewis Hine, A.J. Muste, Alice Paul, A. Philip Randolph, Dorothy Day, Eleanor Roosevelt, Langston Hughes, Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss), Fiorello LaGuardia, Myles Horton, Rachel Carson, Walter Reuther, Thurgood Marshall, Bayard Rustin, Woody Guthrie, Cesar Chavez, Barry Commoner, Ella Baker, Jackie Robinson, Bella Abzug, Pete Seeger, Martin Luther King, Harvey Milk, Ralph Nader, Gloria Steinem, John Lewis and Billie Jean King.