From the Archive: With Hollywood poised to release “Kill the Messenger,” a movie showing how the mainstream U.S. media destroyed journalist Gary Webb for reviving the Contra-cocaine scandal in the mid-1990s, we are reposting Georg Hodel’s 1997 account of how Webb was betrayed by his own editors.

By Georg Hodel (Originally published in summer 1997)

The “Dark Alliance” Contra-crack series, which I co-reported with Gary Webb, has died with less a bang or a whimper than a gloat from the mainstream press.

“The San Jose Mercury News has apparently had enough of reporter Gary Webb and his efforts to prove that the CIA was involved in the sale of crack cocaine,” announced Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz, who has written some of the harshest attacks on Webb. “Editors at the California newspaper have yanked Webb off the story and told him they will not publish his follow-up articles. They have also moved to transfer Webb from the state capital bureau in Sacramento to a less prestigious suburban office in Cupertino.” [Washington Post, June 11, 1997]

Webb got the news on June 5, 1997, from executive editor Jerry Ceppos, who had publicly turned against the series several weeks earlier with a personal column declaring that the stories “fell short of my standards” and failed to handle the “gray areas” with sufficient care. [San Jose Mercury News, May 11, 1997]

In killing additional stories that Webb had submitted, Ceppos said Mercury News editors had reservations about the credibility of a principal Webb source, apparently a reference to convicted cocaine trafficker Carlos Cabezas, who has claimed that a CIA agent oversaw the transfer of drug profits to the Contras. Ceppos also complained that Webb had gotten too close to the story.

Ceppos then ordered Webb to the paper’s San Jose headquarters the next day to learn about his future with the newspaper. On June 6, 1997, as that final decision was coming down, I called Ceppos to protest. I wanted him to understand the human as well as journalistic costs of what he was doing, not just to Webb but to other journalists associated with the story in Nicaragua where I have worked for more than a decade.

I thought he should know that his decision to distance himself from the “Dark Alliance” series — combined with earlier attacks from major American newspapers — had increased the dangers to me and others who have been pursuing this story in the field.

Just as Webb has been under personal attack in the United States, I have faced efforts from former Contras to tear down my reputation in Nicaragua. Ex-Contras also have harassed Nicaraguan reporters who have tried to follow up the Contra-cocaine evidence.

In one paid advertisement, Oscar Danilo Blandon, a drug trafficker who has admitted donating some cocaine profits to the Contras in the early 1980s, called me a “pseudo-journalist” and accused me of having some unspecified links to an “international communist organization.” Blandon also accused Nicaraguan reporters from El Nuevo Diario of “trying to manipulate” members of the U.S. Congress looking into the Contra-cocaine charges.

Former Contra chief Adolfo Calero declared in an article in La Tribuna what he thought should be done to these politically suspect Nicaraguan and foreign reporters. He used metaphorical language that refers to leftist Nicaraguan journalists as “deer” and fellow-traveling foreign reporters as “antelopes.” “The deer are going to be finished off,” Calero wrote on Feb. 2, 1997. “In this case, the antelopes as well.” As a Swiss journalist, I would be an “antelope.”

Less subtly, there have been threatening phone calls to my office. In late May 1997, a male voice shouted obscenities at me over the phone and threatened to “screw” my wife who is a Nicaraguan lawyer representing Enrique Miranda, one of the Nicaraguan cocaine traffickers who has spoken with congressional investigators.

Earlier I had sent Ceppos a letter which complained that his May 11 “column provoked … a series of very unfortunate reactions that seriously affect my working environment and exposes unintentionally everybody here who has been involved in this investigation.” In the phone conversation on June 6, 1997, Ceppos first denied having received the letter, but then admitted that he had it. Still, he refused my request that the letter be published.

A Clear Message

My appeal also did not stop Ceppos from informing Webb later that day that the investigative reporter would be transferred to a suburban office 150 miles from his home where he and his wife are raising three young children. That would mean that Webb would have to relocate from Sacramento or not see his family during the work week. The message was clear and Webb did not miss its significance: he saw the transfer as a clear message that the Mercury News wanted him to quit.

The retributions against Webb were a sad end to the “Dark Alliance” series which has been enveloped in controversy since it was published in August 1996. The series linked Contra-cocaine shipments in the early 1980s to a Los Angeles drug pipeline that first mass-marketed “crack” cocaine to inner-city neighborhoods.

The series drew especially strong reactions from the African-American community which has been devastated by the crack epidemic. In fall 1996, however, The Washington Post and other major newspapers began attacking the series for alleged overstatements. The papers also mocked African-Americans for supposedly being susceptible to baseless “conspiracy theories.”

The furor obscured the fact that “Dark Alliance” built upon more than a decade of evidence amassed by journalists, congressional investigators and agents of the Drug Enforcement Administration who found numerous connections between the Contras and drug traffickers. Some of that evidence was compiled in a Senate report issued in 1989 by a subcommittee headed by Sen. John Kerry. Other pieces came out during the Iran-Contra scandal and still more during the drug-trafficking trial of Panamanian Gen. Manuel Noriega in 1991.

But the Contras were always defended by the Reagan-Bush administrations which saw the guerrillas as a necessary geopolitical counterweight to the leftist Sandinista government that ruled Nicaragua in the 1980s. With a few exceptions, the mainstream media joined the White House in protecting the Contras — and the CIA — on the drug-trafficking evidence. [For details, see Robert Parry’s Lost History: Contras, Cocaine, the Press & ‘Project Truth.’]

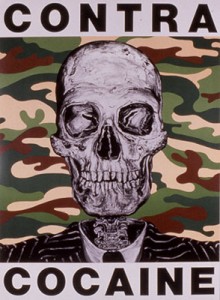

Contra Cocaine

Still, from time to time, even The Washington Post has acknowledged legitimate concerns about Contra drug trafficking. In fall 1996, for instance, after initiating the attacks on “Dark Alliance,” the Post ran a front-page article describing how Medellin cartel trafficker George Morales “contributed at least two airplanes and $90,000 to” one of the Contra groups operating in Costa Rica. The story quoted Contra leaders Octaviano Cesar and Adolfo “Popo” Chamorro as admitting receipt of the contributions, although they insisted that they had cleared the transactions with their contact at the CIA. [Washington Post, Oct. 31, 1996]

The Post did not mention the name of that contact, an omission that angered Chamorro. He told me that the CIA man was Alan Fiers, who served as chief of the CIA’s Central American Task Force in the mid-1980s. Fiers has denied any illicit involvement with drug traffickers, although he testified to the congressional Iran-Contra investigators that he knew that among the Costa Rican-based Contras, drug trafficking involved “not a couple of people. It was a lot of people.”

While admitting some truth to the Contra-cocaine allegations, the Post story stopped short of any self-criticism about the newspaper’s failure to expose the Contra-drug problem in the 1980s as the cocaine was entering the United States. In the Oct. 31, 1996, story, the Post only noted that “a broad congressional inquiry from 1986 to 1988 … found that CIA and other officials may have chosen to overlook evidence that some contra groups were engaged in the drug trade or were cooperating with traffickers.”

The Post then added obliquely: “But that probe caused little stir when its report was released.” With that indirect phrasing, the Post seemed to be shunting off blame for the “little stir” onto the congressional report. The newspaper did not explain why it buried the Senate report’s explosive findings on page A20. [Washington Post, April 14, 1989]. Instead, in fall 1996, the Post and other big papers focused almost exclusively on alleged flaws in “Dark Alliance.”

When that drumbeat of criticism began, Ceppos initially defended the series. He wrote a supportive letter to the Post (which the newspaper refused to publish). But the weight of the attacks from major newspapers and leading journalism reviews eventually softened up the Mercury News. Inside the paper, young staffers feared that the controversy could hurt their chances of getting hired by bigger newspapers. Senior editors fretted about their careers in the Knight-Ridder chain, which owns the Mercury News.

New Leads

In the meantime, Webb and I continued following Contra-drug leads in Nicaragua and the United States. The new information eventually became the basis for Webb’s submission of four new stories to Ceppos. Webb has described these stories as completed drafts although Ceppos called them just “notes.”

Though I have not seen Webb’s drafts, I know they include two stories relating to witnesses in Nicaragua who were part of the cocaine networks of Norwin Meneses, a longtime Nicaraguan drug trafficker who was based in San Francisco and who collaborated closely with senior Contra leaders.

Meneses’s operation surfaced with the so-called Frogman case in 1983 when the FBI and Customs captured two divers in wet suits hauling $100 million worth of cocaine ashore at San Francisco Bay. The federal prosecutor ordered $36,020 captured in that case be given to the Contras who claimed it was their money.

For the new “Dark Alliance” stories, we interviewed Carlos Cabezas who was convicted of conspiracy in the Frogman case. Cabezas insisted that a CIA agent — a Venezuelan named Ivan Gomez — oversaw the cocaine operation to make sure the profits went to the Contras, not into the pockets of the traffickers.

Last year, Cabezas outlined his claims in a British ITV documentary. “They told me who he [Gomez] was and the reason that he was there,” Cabezas said. “It was to make sure that the money was given to the right people and nobody was taking advantage of the situation and nobody was taking profit that they were not supposed to. And that was it. He was making sure that the money goes to the Contra revolution.”

The ITV documentary, which aired on Dec. 12, 1996, quoted former CIA Latin American division chief Duane Clarridge as denying any knowledge of either Cabezas or Gomez. Clarridge directed the Contra war in the early 1980s and was later indicted on perjury charges in connection with the Iran-Contra scandal. He was pardoned by President George H.W. Bush in 1992.

The additional “Dark Alliance” stories also would have examined the claims of other Contra-connected drug witnesses in Nicaragua as well as the career problems confronted by DEA agents when they uncovered evidence of Contra drug trafficking. But prospects that the full Contra-cocaine story will ever be told in the United States have dimmed with the shutting down of “Dark Alliance.”

I am also afraid that Ceppos’s decision to punish Webb will strengthen the campaign of intimidation inside Nicaragua. But beyond the personal costs to Webb and me, Ceppos’s actions sent a chilling message to all journalists who someday might dare investigate wrongdoing by the CIA and its operatives.

What’s especially troubling about this new “Dark Alliance” tale is that the investigative spotlight was turned off not by the government, but by the U.S. national news media.

Editor’s Note: In 1998, a CIA Inspector General’s report admitted that the Contras were deeply implicated in the cocaine trade and that CIA officials were both aware of that fact and obstructed official investigations of the crimes. But the major U.S. news media downplayed or ignored those findings. Thus, Webb and other journalists who had pursued this grim chapter of U.S. history found their careers ruined.

Because of threats and harassment in Nicaragua, Georg Hodel moved back to his native Switzerland where he died in June 2010. Unable to find decent-paying work in his profession, Webb committed suicide in December 2004. The movie, “Kill the Messenger,” is set for release on Oct. 10. [For more on this topic, see Consortiumnews.com’s “The CIA/MSM Contra-Cocaine Cover-up”]