If Official Washington were not the corrupt and dangerous place that it is, the architects and apologists for the Iraq War would have faced stern accountability. Instead, they are still around holding down influential jobs, making excuses and guiding the world into more wars, as ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar notes.

By Paul R. Pillar

The Iraq War, as Heather Marie Stur tells us, should not be lumped together with the Vietnam War as blindly and repeatedly as many seem wont to do. Although the two military expeditions both rank among the costliest blunders in American history, there are indeed many differences between the two.

Stur is correct to emphasize differences over similarities, but she completely misses the most significant differences, significant partly because of their implications for avoiding similar blunders in the future.

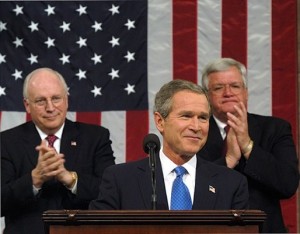

President George W. Bush pauses for applause during his State of the Union Address on Jan. 28, 2003, when he made a fraudulent case for invading Iraq. Seated behind him are Vice President Dick Cheney and House Speaker Dennis Hastert. (White House photo)

Difference number one sets the invasion of Iraq in 2003 apart not only from the intervention in Vietnam but from almost every other substantial use of U.S. military force. There was no policy process leading to the decision to launch the war.

Whether invading Iraq was a good idea was never on the agenda of any meeting of policymakers, and never the subject of any options paper. Thus no part of the national security bureaucracy had any opportunity to weigh in on that decision (as distinct from being called on to help sell that decision to the public).

Sources of relevant expertise both inside and outside the government were pointedly shunned. The absence of a policy process leading to the decision to launch the war is the single most extraordinary aspect of the war.

The U.S. intervention in Vietnam was entirely different. Although as the war went on the decision-making of Lyndon Johnson and his Tuesday lunch group became increasingly closed, the original decisions in 1964 and 1965 to initiate the U.S. air and ground wars in Vietnam were the result of an extensive policy process. The bureaucracy was fully engaged, and the policy alternatives exhaustively discussed and examined. However mistaken the decisions may have turned out to be, they could not be attributed to any short-cuts in the decision-making process.

A second distinctive aspect of the Iraq War is that it was a war of aggression. It was the first major offensive war that the United States had initiated in over a century. Every overseas use of U.S. military force in the Twentieth Century was either a minor expedition such as ones in the Caribbean or, in the case of major wars, a response to the use of force by someone else. The U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia was a case of the latter: a direct response to the use by North Vietnam of armed insurgency to take over South Vietnam.

This is another respect that sets the Iraq War apart not only from Vietnam but from many other U.S. wars, including a couple of relatively recent ones that Stur incorrectly likens to the Iraq War. Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2001 was a direct response to a terrorist attack by a group that was resident in Afghanistan and allied with its regime. Operation Desert Storm in 1991 was a direct response to blatant aggression by Iraq in invading and swallowing Kuwait. When that aggression was reversed by expelling the Iraqis from Kuwait, the U.S. mission really was accomplished.

Sometimes earlier wars have a lot to do with explaining much later events, and the centenary of World War I has stimulated some interesting analysis of how that war set in train events that still bedevil us today, but Stur’s attempt to say something similar about the war in 1991 is mistaken.

Some neoconservatives grumbled about Saddam Hussein being left in power, but the grumbling did not have to do with any problems created by Operation Desert Storm; it instead reflected the neocons’ desire for other reasons to have a larger regime-changing war in Iraq.

This gets us to a third major difference, which is related to the first one. The Iraq War of 2003 was the project of a small, willful band of war-seekers, what Lawrence Wilkerson has called a “cabal”, who managed to get a weak and inexperienced president to go along with their project for his own political and psychological reasons.

An assiduous selling campaign lasting more than a year, which exploited the post-9/11 political mood by conjuring up chimerical alliances with terrorists, mustered enough national support to launch the war. But the base for starting the project was always quite narrow.

By contrast, the United States sucked itself into the Vietnam quagmire on the basis of a very broadly held conventional wisdom about a global advance of monolithic communism, falling dominoes, and the need to uphold U.S. credibility. At the time of the intervention, opposition to the intervention was exceedingly narrow.

The Gulf of Tonkin resolution authorizing the use of military force in Vietnam passed against only the lonely nay votes of Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening in the Senate and no opposition at all in the House. The conventional wisdom pervaded the public and the media, including prominent journalists such as David Halberstam and Neil Sheehan who only later would become identified with publicizing the war’s faults and fallacies.

Looking back on the mistakes involved in the Vietnam War became a national exercise in painful retrospection. It included soul-searching by some of those most directly involved in launching the U.S. expedition; some of the most candid and insightful came from former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. The difference with the post-war posture of the people who brought us the Iraq War has been stark. Despite the much narrower original responsibility for that war, mea culpas from those who promoted it have been hard to find. The promoters have instead tried to find creative ways to blame the damage they caused on those who later had to clean it up.

All of this has implications for avoiding comparable blunders in the future. The Cold War is over, and the parts of the Vietnam-era conventional wisdom involving the nature of international communism are gone as well.

We still see similar thought patterns, however, applied in other ways, especially with notions of upholding credibility and domino-like scenarios of geographically expanding threats. There still is Cold War-type thinking that treats Russia as if it were the Soviet Union, and that treats radical Islam as if it were a monolithic foe that is our enemy in a new world war.

Avoiding another blunder like the Iraq War means being wary not only of these sorts of thought patterns but also of a more direct hazard. The neocons who brought us that war are not only unrepentant but also very much around and still selling their wares. We most need to remember what they sold as the last time, and not to buy anything from them again.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

When I read this above ignorant summary of the US involvement in Vietnam I cringe, quoting:

“The U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia was a case of the latter: a direct response to the use by North Vietnam of armed insurgency to take over South Vietnam.”

Nope, in the later 1940s the US re-installed the French as a colonial power and ignored Ho Chi Min’s entreaties to help all of Vietnam become an independent state, then the French lost that US backed war in the mid 1950s and it was agreed that the entire country would vote for a new Vietnamese leader, Ho won, the US didn’t like that result and remained effectively occupying the south into the 1960s. At that time the Vietnamese in the north turned to the Soviets for more and more help, in a war against US occupation of the south. In the mid1960s, based on lies about the Gulf of Tonkin, this low level war lead to a wider war, usually called the Vietnam War in the US.

I’m really surprised to see such ignorance posted in an essay here.

Right the 2003 invasion of Iraq was significantly different, but it’s not as if the US didn’t keep up air attacks on parts of Iraq for the entire 1990s.

28 years at CIA and Pillar doesn’t know this basic history of the US involvement in Vietnam, or he knows and expects us to believe the lies he’s selling. And yeah I mean lies.

The problem is that this kind of thing now calls into question any thing else Pillar claims.

Johnson issued Executive Order 273 the day after Kennedy was buried. That order reversed Kennedy’s Executive Order 263 outlining the drawdown and withdrawal from Vietnam. Rather than lengthy or thoughtful deliberation as a response to aggression, E.O. 273 was a policy decision implemented immediately after a de facto regime change. But even if, by some twisted logic, Vietnam could be rationalized as a response to aggression, what about Laos and Cambodia? Professor Pillar is clearly “tap dancing” around the truth here. In fact, I ain’t seen this much tap dancing since Sammy Davis Jr. died.

F. G. Sanford:

Right, that LBJ change order after JFK was murdered too.

Then there’s idea of LBJ agreeing to expand the war to go along with the wishes of rightwing democrats–mostly dixiecrats LBJ wanted to vote for the Civil Rights Act, but also people like Henry “Scoop” Jackson.

The US involvement goes back to the 1940s when the US went so far as to use defeated (and hated) Japanese occupation troops as police. This is before the re-installation of the French as a colonial power.

It’s not exactly tap dancing by Pillar, it’s an incredibly artificial cut-off, I’m really really surprised to have read anything like this at this website.

This is like the most simplistic “reporting” in the New York Times or at say NBC news. (Both the Times and NBC/CBS would usually do a better job.) And it’s the absolute line that FoxNews draws: There being nothing but communist aggression as cause of the Vietnam war, in that mentality.

For a starter I’m going along with you two.

Then, WOW,

All of this for a remark of: – Iraq War, as Heather Marie Stur tells us, should not be lumped together with the Vietnam.

Was Heather Marie Stur in South Vietnam when US Army was in South Vietnam bringing American Democracy? Looking at recent photos of her it doesn’t look like she was around when I was (and still I’m) in the Asia region 60-yrs ago. Of recent she is on a Fulbright scholarship in Ho Chi Minh City. So whatever she says should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Also don’t be too hard on Paul R. Pillar with 28-yr behind him in the CIA it is not unusual that it shows in his writing when it concerns American behavior in other parts of the world.

• Larusmarinus

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v…

What can more recent wars teach us about the perils and potential consequences of attempting to implement democracy through military force?, Heather Marie Stur is asking.

• Here is Vietnam war veteran Andrew Bacevich’s answer :

• Let’s look at what US military intervention in Iraq has achieved, in Afghanistan has achieved, in Somalia has achieved, in Lebanon has achieved, in Libya has achieved. I mean, ask ourselves the very simple question: is the region becoming more stable? Is it becoming more democratic? Are we alleviating, reducing the prevalence of anti-Americanism? I mean, if the answer is yes, then let’s keep trying. But if the answer to those questions is no, then maybe it’s time for us to recognize that this larger military project is failing and is not going to succeed simply by trying harder.

Andrew Bacevich,Chaos in Iraq, 20 June 2014 : http://billmoyers.com/episode/…

At some point in time America will need to hold it’s leaders accountable for their actions. If The U.S. doesn’t do this, then will accountability be prosecuted by some outside force? I am sorry, but I fear there will someday be a worldly backlash so great it will make America’s head spin. Our global leadership isn’t leadership at all. Instead, America has become the mean spirited bully.

Keep your eye on Germany, and France. Also watch the U.S. Dollar dissolve as the worlds reserve currency.