There is cognitive dissonance in the way Americans view their Declaration of Independence of 1776, with pride over its assertion of fundamental human rights but in denial about the hypocrisy of Thomas Jefferson and other Founders who owned and abused their slaves, as Danny Schechter reflects.

By Danny Schechter

The wheel of the calendar has turned again, and July Fourth is upon us once more, a day for the consumption of 155 million pounds of hot dogs and the blasting off of fireworks. Seventy-five percent of the pyrotechnics industry’s revenues ignite on the federal holiday marking the anniversary of American Independence.

Recall that one of the pledges in the document of documents was a “Decent Respect for The Opinions of Mankind,” a vow undercut somewhat by a ruling by an appointed intelligence advisory body this past week, based on who knows what legal foundation, that U.S. spying on mankind is now and forevermore “legal” under our Constitution.

Back in 1776, the War for Independence had been on for more than a year before the often feuding and disunited politicians of the Continental Congress decided a declaration was needed. It followed from a resolution by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia that began: “Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

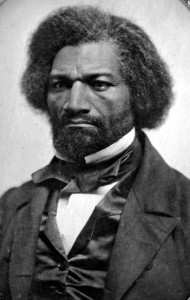

In the 238 years since of all the oratory about “our” independence nothing surpasses the speech by abolitionist, editor and former slave Frederick Douglass, whose oration about July Fourth deserves to be much better known.

His speech has the title, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” It was delivered on July 5, 1852, nearly nine years before the eruption of the Civil War, the conflict over the Confederacy’s secession from the Union. Douglass began slowly:

“Who could address this audience without a quailing sensation, has stronger nerves than I have. I do not remember ever to have appeared as a speaker before any assembly more shrinkingly, nor with greater distrust of my ability, than I do this day. A feeling has crept over me, quite unfavorable to the exercise of my limited powers of speech. The task before me is one which requires much previous thought and study for its proper performance. I know that apologies of this sort are generally considered flat and unmeaning.

“The papers and placards say, that I am to deliver a Fourth [of] July oration. This certainly sounds large, and out of the common way. The fact is, ladies and gentlemen, the distance between this platform and the slave plantation, from which I escaped, is considerable, and the difficulties to be overcome in getting from the latter to the former, are by no means slight.

“That I am here today is, to me, a matter of astonishment as well as of gratitude. You will not, therefore, be surprised, if in what I have to say I evince no elaborate preparation, nor grace my speech with any high sounding exordium. With little experience and with less learning, I have been able to throw my thoughts hastily and imperfectly together; and trusting to your patient and generous indulgence, I will proceed to lay them before you.

“This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the Fourth of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. This, to you, is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God. It carries your minds back to the day, and to the act of your great deliverance; and to the signs, and to the wonders, associated with that act, and that day. This celebration also marks the beginning of another year of your national life; and reminds you that the Republic of America is now 76 years old. I am glad, fellow-citizens, that your nation is so young.”

He went on and on, praising the Founders and sympathizing with their cause before dropping the bomb he had, no doubt, been invited to drop, a condemnation of slavery a “peculiar institution” what a euphemism that was that some historians say was a prime reason for the revolt in the colonies, based on the opposition to Britain’s decision to end its role in this inhumanity. Ending slavery was a choice that many of the signatories to the Declaration opposed, no doubt, in part, because they, with whatever doubts or trepidations, held slaves themselves.

Douglass did not rush to get to his point, saying to all assembled, “Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

He did not mince words: “Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.”

So much, back then, for American “exceptionalism,” and so much for the deep debate that is still with us when, in rare moments, our polity and media even recognize the great gaps and inequalities that are dividing and impoverishing the nation.

Douglass ended his soaring declamation with hope, not despair, calling for a renewal of the values of the Declaration and a renewed commitment to justice. He quoted, the “fervent aspirations” of William Lloyd Garrison:

“God speed the year of jubilee, The wide world o’er! When from their galling chains set free, Th’ oppress’d shall vilely bend the knee, And wear the yoke of tyranny, Like brutes no more. That year will come, and freedom’s reign, To man his plundered fights again, restore.”

Amen to that call to restore “plundered rights” on that July Fourth and all that would follow.

Newsdissector Danny Schechter blogs at Newsdissector.net and works on Mediachannel.org. His latest book is Madiba A-Z: The Many Faces of Nelson Mandela. (Madibabook.com) Comments dissector@mediachannel.org.

Thanks for this article and for reminding us that we, as a nation, are still far away from equality and justice for all.