United Farm Workers founder Cesar Chavez, with quiet dignity and nonviolent tactics, rallied millions of Americans behind the cause of oppressed farm workers in the 1960s, a remarkable moment recalled in a new movie by Diego Luna, interviewed by Dennis J Bernstein.

By Dennis J Bernstein

Cesar Chavez, founder of the United Farm Workers and the subject of a new movie, was an unlikely leader of a movement that not only unionized one of the most oppressed segments of American labor but galvanized much of the United States behind the justice of their nonviolent cause.

Chavez, who died in 1993 at the age of 66, was a person known for listening to others, not for loud exhortations. And, he infused the movement with a quiet dignity that won support from a broad cross-section of Americans who supported the farm workers with a boycott of grapes that forced growers to recognize the union.

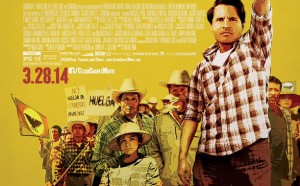

Now, Chavez’s struggle is the focus of a new movie, “Cesar Chavez: History Is Made One Step at a Time,” which itself represented a struggle for writer-director Diego Luna who has spent the last four years raising the money to make the picture. Luna, who is also an actor (starring in Alfonso Cuarón’s 2001 film Y Tu Mamá También ), has had no shortage of roles being offered to him, but he considered the making of “Cesar Chavez” a work of love and commitment.

“It’s important we don’t forget this is part of American history,” he told Dennis J Bernstein in an interview for the Flashp[oints show on Pacifica Radio. The film opened in theaters on Friday.

DL: I am happy to be to talk about the film. It is a feature film which talks about ten years in the life this man and everyone around the movement. It’s about the amazing message they sent in this country in the 1960s, how they created the first union for farm workers in this country, and the grape boycott they did to connect with consumers in America.

DB: I would like to ask you about the multiple struggles to make the film.

DL: At the beginning, everyone was very supportive and the film business was shocked that there was no film about Cesar Chavez. When we tried looking for the financing, that’s when we started to find trouble. Not many wanted this film to be made, or to participate as financiers. We went back to Mexico and started raising money there. We got together a good 70 percent of the financing, and then we found the right partners on this side of the border. We had to go the other way around. It was a paradox. We had to go to Mexico to tell the story of an American hero.

DB: This film that you spent four years on, what was at the core for you? Why did you decide to take this on, and what do you want the American people to come away with from this film?

DL: First of all, people need to learn about who Cesar was. You would be surprised at how little is known about the life of Cesar. I’ve been asking and finding out that many people don’t know who he was, what they achieved, what they had to go through. It’s important we don’t forget this is part of American history. It’s important for young people to know that this happened, is part of who they are and is a fantastic inspiring story that can show that change is in your hands.

It’s a powerful film for kids to see. But it’s also an important one for our community. If you are part of the Latino community, there are not many films that celebrate who we are. There are not many chances to go to the cinema and see a film that is about us. This one is, so it’s about that journey. It’s one of so many stories about our community that should be celebrated. It is about sending the message to everyone in Hollywood that our stories have to get to the screen.

DB: What did you learn from this film? What were you surprised about that you didn’t know before?

DL: I knew they achieved something, but I didn’t know the whole strategy behind it. I didn’t know how ahead of their time they were. They organized that boycott with a non-violent movement, and sent a message to this country that a change was happening if we got involved. They went out and connected with consumers. They made a movement viral before viral was even in their heads. They connected with people in the whole country who thought they had nothing in common with farm workers, and then realized they had a lot in common.

Parents talked to other parents, mothers talked to mothers, saying when you buy a grape, you are supporting child labor. My six-year-old cannot go to school because he is working to support the family. We don’t make enough money to assure we can give an education to our kids. Then mothers stopped buying grapes. It’s a simple as that. I learned that it’s about telling personal stories. About getting out there and telling your story and finding out who thinks like you do. We are not alone here.

DB: It’s been over 50 years since Edward R. Murrow made his famous documentary “Harvest of Shame.” As I speak to you, between 1,000 and 1,100 undocumented workers who do some of the hardest work that we all depend on, are being removed from this country, at an accelerated rate. We are going to reach about two million under Obama. How do you see your film in that context? Would you like it to play a part in this transformation, bringing awareness to help end this type of suffering?

DL: I definitely hope this film participates in the bigger struggle that is happening today by reflecting on how this country can allow more than 11 million workers not to have the rights of those who consume the fruit of their labor. Arturo Rodriguez, [president] of the United Farm Workers, said that 80 percent of the workers are undocumented. That is ridiculous. It is a new form of slavery, where these people are feeding the country but can barely feed their families.

I was talking to some people in Miami the other day who did a little documentary on the fields, and they found eight-year-old kids working still today. Conditions have changed for a few farm workers – in a few places in this country they have better conditions. But there is still a big change needed. It will happen if we consumers get involved, if we make sure we understand that their stories are our stories. I think the great and beautiful message of this movement that we need to be reminded of today is that it was about being united, about finding those things that connect each community in order to find the strength to collapse the very powerful industry in this country. They achieved it.

DB: Have you been to Arizona lately? How do you think your film is going to play in Phoenix, where being a brown person and speaking Spanish can be a major crime that can cost you up to your life?

DL: I was there. We did a big screening of the film, with a big celebration for the Cesar Chavez Foundation and the UFW. We were very loud and clear about the message that needs to be sent from Arizona to the rest of the country. Our community is very important to this country today. What this community has given to this country needs to be recognized. We cannot call this the land of freedom without immigration reform. It just doesn’t connect.

DB: Earth Day is coming up. Cesar Chavez was very conscious of the earth, the vegetables. The farm workers are constantly struggling with the chemistry that makes the crops grow so well. Can you talk about his broad consciousness around food, eating and the bigger picture around the work?

DL: Today people worry so much about being organic, how the food grows, what is inside the product you are eating and how it affects you. But not many people think about the labor, the work behind it. You don’t want o be part of a chain that is abusing people, that is making kids work, and does not respect the basic rights that every human being should have. You don’t want to be part of that.

So we cannot worry so much about organic or not organic or grass fed. We need to think about all the human work behind the product we are eating. That is something Cesar brought attention to. There was a big boycott organized around pesticides, yet today pesticides are still a big, big issue in the health of this community. It is ridiculous that we are still debating so many things that to me sound so obvious.

DB: What is the role that Dolores Huerta played? How did her first-hand knowledge from being in the fields impact her work as the co-founder of the UFW with Chavez? Since she is still with us, was her testimony and experience an important part of making the film?

DL: Yes, but not just Dolores – there’s many people. Since Cesar passed away, and we wanted to honor him, we sat down with his family. I worked closely with Paul Chavez who runs the Cesar Chavez Foundation, and many other people who were part of this movement like Gilbert Padilla and Jerry Cohen. I worked closely with Mark Grossman, who was his publicity person and who traveled more than 10 years with Cesar all around the country.

I am not doing a film that should play as a history lesson. It is a film that has to work as a film. It must connect and engage emotionally with the audiences. It’s all about that personal and intimate angle that you can get. I concentrated a lot about what happened before and after the big events that are well documented – before that great speech, before the pilgrimage to Sacramento. What mattered to me were the little moments when he was a husband, a father.

To get all that information, I needed everyone around Cesar to feed me with the information and details you cannot find in books. Dolores read the script and gave us notes, then she saw the film. The family gave me tons of notes. Helen Chavez, his wife, was very important. I had a beautiful conversation with her for 3-4 hours. She came to say hi and give us her blessing. She started talking, and talking and suddenly she really opened up and gave us so many details that I had to go back and re-write the script.

DB: That’s very beautiful. I assume you recorded that conversation?

DL: Yes, I recorded it. When she started talking about Fernando, I said this is going to be the core of the film – his relation with this son. Cesar was just a man like us all. He was a father struggling to communicate with his son. While Cesar is doing this amazing sacrifice, he was giving away the opportunity to be next to his kids, for change to happen, to be able to deliver something better for them and the people around them.

From the perspective of his son, he’s been abandoned. That’s a very dramatic thing and I don’t know if I would be able to take it as far as Cesar did, as a father. That is something that can connect with everyone. We are all sons, parents. We can see it from one or the other perspective. That is what reminds us that this is just another regular man. He said many times, this is the story of an ordinary man who did something extraordinary.

DB: His declaration for non-violence, fasting, made this ordinary man compared with people like Mahatma Gandhi. Are there films that you used as models? People are talking about films like “Salt of the Earth” and “Grapes of Wrath.” Are these films that you would like this film to be contextualized with?

DL: These are films that I saw in the process of making this one, and they definitely served as an inspiration. What I wanted to avoid was to create a saint, to idolize a character so that he becomes unreal. I always wanted to remind everyone that this is a movement of people who have their feet on the ground. They are here with us. We could be one of them. We could bring change to whatever issue we have in our community. We can be a part of change.

I wanted to do a film that would feel personal and intimate. It would have its epic moments, but would always remind you that it’s more about the feeling that you are the only one allowed into a personal world, to feel the intimacy. Trying to portray the family was very important to me. It was a very complex family with eight kids that spoke English to their kids, but Spanish to their parents. I showed the troubles of Helen, as the mother who had to work as well as contribute to the union, where she worked hard. Cesar was great at organizing, putting the strategy together. He wasn’t a great speaker. He didn’t like attention, to grab the mike and be in front of everything.

DB: He was better at silence.

DL: Yes, silence, and listening was a great tool for him. It was great for his community because they were ignored for such a long time. Somebody finally came and took the time to listen to their stories. It gave them confidence. I love that. I always wanted the film to feel real, that you could touch and smell it, to feel a part of it. I didn’t want people to feel alienated, that it was the story of someone that is so special that it’s unreachable.

I hope people can see the film and choose to be part of what is going on right now. This is not just about Cesar Chavez, but is about our whole community that needs celebration. They did amazing things. The film should be part of that celebration.

Dennis J Bernstein is a host of “Flashpoints” on the Pacifica radio network and the author of Special Ed: Voices from a Hidden Classroom.