Exclusive: A half-century ago, religious clashes in Vietnam — leading to a dramatic photo of a Buddhist priest burning himself alive — shocked the U.S. government and drove it deeper into the morass of the Vietnam War, a confluence of religion and politics that remains relevant today, as war correspondent Beverly Deepe Keever explains.

By Beverly Deepe Keever

The 40th anniversary of the withdrawal of American troops from the Vietnam War was recently commemorated, but ignored was the 50th anniversary of an incident that led to U.S. combat units being sent to the war zone in the first place.

That bloody event is probably not even recalled by the two Vietnam veterans now heading the Pentagon and State Department, Chuck Hagel and John Kerry, respectively. Yet it turned out to be an indelible turning-point in the history of the Vietnam War. And, a half-century later it still warns a nuclearized world about the power of organized religious groups and the perilous politics of regime change.

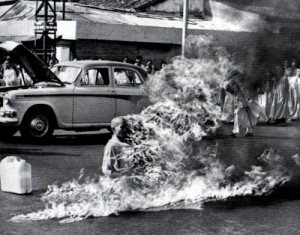

Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc self-immolating in a protest against the U.S.-backed government of Ngo Dinh Diem. (Photo credit: Malcolm Browne; Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Sketchily reported at first, an initial 134-word wire story described seven persons killed when a grenade was thrown into a crowd of 3,000 in a Buddhist demonstration that was Communist-inspired, according to the Vietnamese government headed by President Ngo Dinh Diem, a Roman Catholic.

The bloodshed occurred on May 8, 1963, as religious followers heralding Buddha’s birthday began flying flags in Hue just as the Diem government began enforcing a long-ignored ban on displaying religious flags outside of religious organizations. Hue was the home of Diem’s brother, Archbishop Ngo Dinh Thuc, who had hoisted yellow-and-white Vatican flags earlier in the month while celebrating the 25th anniversary of his ordination as bishop.

Undergirding Buddhist grievances was the French-imposed Decree No. 10, which Diem had retained, labeling Buddhism as an association, rather than a religion, thus restricting the power, rights and flag-flying privileges of its followers compared to those of Roman Catholics.

Perched along the South China Sea 400 miles north of Saigon, and 50 miles south of the demilitarized zone with North Vietnam, Hue was a storybook city bisected by the Perfume River, where sampans glided for vendors selling a sweet brew concocted of lotus seeds. A key center of Buddhist scholarship, it served as the one-time royal capital of Vietnam that still glistened with ruby-colored citadels and Forbidden-City-styled Palace.

Saffron-robed Buddhist bonzes and others contested the government’s version of the Hue melee. They told of eight, not seven, deaths, including children, from an explosion, from a Catholic government official ordering troops to fire, and from armored cars crushing demonstrators. The killings were protested the next day by 10,000-plus Buddhist demonstrators in Hue.

Throughout the sultry summer, Buddhist protesters thrust Vietnam onto the world stage, and U.S. television screens, with a self-perpetuating chain reaction of fasting, sit-down strikes, student walkouts, mass meetings, news conferences, a plea to the United Nations and skirmishes with police. It was like a long-dormant volcano rumbling toward eruption.

Rumors circulated in Saigon that several Buddhist bonzes had volunteered to commit suicide by setting themselves afire to highlight their demands. On June 8, 1963, one elderly bonze, Thich (Venerable) Quang Duc told me, “To die is the only thing I want because the government is indirectly destroying the civilization of the Vietnamese people, which depends on the Buddhist culture.” I cabled these words in his last interview to Newsweek and the London Sunday Express.

Three days later, Quang Duc moved from a sedan, sat on a brown cushion dropped onto to a dusty road and was doused with gasoline by two other bonzes. Then he stretched his hands across his brown robe and lit a match.

“In a flash, he was sitting in the center of a column of flame, which engulfed his entire body,” and then he was still, recounted AP’s Malcolm Browne, who captured the suicide on film.

The burning-bonze photo horrified the world. Upon first seeing it, President John Kennedy exclaimed, “Jesus Christ!” He added: “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.”

The U.S. support for Diem grew shaky. Kennedy, America’s first Catholic president gearing up for re-election the next year, was increasingly embarrassed by the protests alleging religious persecution from the U.S.-backed president of South Vietnam who was also a Catholic.

The result: regime change in Saigon. After years of U.S. support that began in 1954 under President Eisenhower, the Kennedy administration encouraged Vietnamese generals to overthrow Diem on Nov. 1, 1963.

“For the military coup d’etat against Ngo Dinh Diem, the U.S. must accept its full share of responsibility,” the Pentagon Papers documented in 1971. “Beginning in August of 1963, we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government.”

The coup and the subsequent murder of Diem (and his younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu) stunned the world. Lyndon Johnson, who was then vice president, later called the coup “the worst mistake we ever made.” More than 32 years later, Robert McNamara, who was Secretary of Defense at the time, wrote, “I believe that the United States support of the overthrow of President Diem was a mistake.”

North Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh, upon hearing the news, chortled, “I could scarcely believe that the Americans would be so stupid.”

The regime change led to a revolving door of upheavals throughout the Vietnamese government and armed forces. Three months after the Diem coup, most chiefs of the 41 provinces had been replaced at least once, major military commanders had been replaced twice and, as McNamara subsequently told President Johnson, “the political structure extending from Saigon down into the hamlets disappeared.”

The military junta that ousted Diem lasted 89 days until it was, in turn, toppled by an upstart general named Nguyen Khanh. These twinned coups were described by the leading pro-Communist leader in South Vietnam, Nguyen Huu Tho, as “gifts from heaven for us.”

Khanh lasted only 390 days before being ousted by other generals and exiled abroad on Feb. 24, 1965. Six days later, U.S. and South Vietnamese warplanes began graduated-turning-into-sustained bombing of North Vietnam. In another six days, on March 8, 1965, the first American combat unit strode ashore near the demilitarized zone with North Vietnam.

It would take another 2,943 days (or eight-plus years) for the last American soldier to withdraw from Vietnam on March 29, 1973, as the U.S. suffered the first clear military failure in its history.

The Hue incident of 50 years ago was a warning about the geopolitical hazards that can arise from religious ferment as well as a reminder about the dangerous temptation of regime change. Those warnings were inadequately addressed in the 1960s and have continued to confound policymakers in the 21st Century.

Beverly Deepe Keever was a Saigon-based correspondent who covered the Vietnam War for a number of news organizations. She has just published a memoir, Death Zones & Darling Spies.

There were many Buddhist monks and Buddhist faithfuls joined National Liberation Front (NFL) in order to get rid of the Republic of South Vietnam. NFL was established in 1960 before the incident of Thich Quang Duc’s self-immolating happened. After winning the war in 1975, the North communist Vietnamese government destroyed NFL and killed those Buddhist monks and the faithfuls. Buddhist faithfuls felt betrayed from that annihilation.

All North Vietnamese troops were disguised as NFL to cover up the invasion.

Very interesting and distressing. Unfortunately Communist parties tend to be much more disciplined(and ruthless) than other left groups and thereby are the ones to take and consolidate power after a revolution.

Stalin did the same to many of the heroes of the Bolshevik revolution, and his own generals.

The Naval Institute Press (not a left wing outfit at all) has a book about the black operations in Vietnam. Says that dropping off saboteurs with only 6 weeks training in North Vietnam started the war.

Why was the Turner Joy in North Vietnamese waters? Dropping off saboteurs. Go america.

If you want to read the Naval Institute Press’s book on black operations in the Korean War.

How did that start? The americans were dropping saboteurs off of North Korea then. Even the Soviets were doing their nuts about that. The diplomatic correspondence was printed for a short while after the USSR fell apart. They were screaming at the Koreans to stop, they were going to start a freaking war with the US.

Worked twice. Started two wars with millions dead but the Merchants of Death made a few bucks.

Slight misinterpretation of the events, the war was already going; what the Tonkin Gulf incident did was give LBJ an excuse to begin what he wanted, all out bombing on the North. It was not a beginning but a dramatic escalation. The first person to receive intel at the Pentagon from the Navy was none other than Daniel Ellsberg(described in his excellent book Secrets), at that time assistant to the under secretary to the Secretary of Defense. He quickly noticed something incongruous about the reports; that the destroyer had reported having over 20 torpedoes fired at it; which were more torpedoes than the US thought N. Vietnam had. Never mind if someone fires that many, your gonna get hit. The truth of the matter was that under certain weather and sea conditions it is possible for a sonar man to mistake the ships own propeller turbulence for incoming. Which is what was later realized. LBJ and co. took what was a mistake(not a premeditated set up) and ran with it publicizing the lie that it was a North Vietnamese torpedo attack, much later to be disproven in Congress. Also, the Maddox was assisting a commando operation on North Vietnam; which by international law made it fair game had it actually been attacked. There were two destroyers, the Maddox and the Turner Joy, the latter is now a museum in Bremerton Washington. The Maddox was the focus of the event.

Ellsberg,long after he published the Pentagon Papers, discovered the contents of a top secret file that he was not supposed to see during his employment at the Pentagon. That file revealed that every US President had been informed that intervention in Vietnam was unlikely to succeed. That was the real “Secret”about the Vietnam War- what a horrible, monstrous waste, testimony to the consequences of adherence to the fanatical obsession with “anti-communism”.

The Naval Institute Press (not a left wing outfit at all) has a book about the black operations in Vietnam. Says that dropping off saboteurs with only 6 weeks training in North Vietnam started the war.

Why was the Turner Joy in North Vietnamese waters? Dropping off saboteurs. Go america.

If you want to read the Naval Institute Press’s book on black operations in the Korean War.

How did that start? The americans were dropping saboteurs off of North Korea then. Even the Soviets were doing their nuts about that. The diplomatic correspondence was printed for a short while after the USSR fell apart. They were screaming at the Koreans to stop, they were going to start a freaking war with the US.

Worked twice. Started two wars with millions dead but the Merchants of Death made a few bucks.

I was in Vung Tau during these events. 60 Km from Saigon. I had a jeep overturned and burned by Buddhist crowds. I subsequently was in Viet Nam during several coups for 4 more years, until after the Tet Offensive in 68. The most curious event, rarely mentioned, was in October and November of 1963, what appeared as a general withdrawal of troops and material, after Kennedy’s Assassination, the withdrawal was stopped and subsequent material started coming into the country. Followed the next year by the Introduction of combat troops.

This story describes a continuity, but leaves out what was almost a abrupt and critical change in that continuity. President Kennedy, unlike his successors, realized Vietnam was a hopeless cause for the Americans, just as he had in Laos and Cambodia, and ordered the withdrawal of 1000 advisors to be followed by more. Until then the US troops were largely trainers and tacticians.(see John Newman, JFK and Vietnam). After Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson immediately reversed that decision and began the escalation to full scale war with American troops. Of course he had to get elected; so he held off going full bore until after campaigning, “I’ll not send Amurican boys to go do what Asian boys ought to do for themselves”, against that rabid hawk Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

BTW Kennedy did authorize the coup but was upset that Diem and brother were murdered in the process. I believe it was Henry Cabot Lodge who passed the word to the generals for regime change.

There were many factors that fed into JFK’s murder one of which was his repeated frustrating of the Joint Chiefs’ extremely dangerous and hyper aggressive strategies: Bay of Pigs, Cuban Missile Crisis, Laos, Cambodia and now Vietnam all events in which they considered him dangerously weak for not following through to their liking. He was also laying down the law to Israel that their nuclear ambitions were unacceptable-quite different from later administrations. So if you wonder why he died just remember he pissed off: the Pentagon, the CIA, the Mafia and the Israelis, not a good formula for longevity.

I think D.A. Jim Garrison summed it up best:

“In retrospect, the reason for the assassination is hardly a mystery. It is now abundantly clear … why the C.I.A.’s covert operations element wanted John Kennedy out of the Oval Office and Lyndon Johnson in it. The new President elevated by rifle fire to control of our foreign policy had been one of the most enthusiastic American cold warriors…. Johnson had originally risen to power on the crest of the fulminating anti-communist crusade which marked American politics after World War II. Shortly after the end of that war, he declaimed that atomic power had become ‘ours to use, either to Christianize the world or pulverize it’ — a Christian benediction if ever there was one. Johnson’s demonstrated enthusiasm for American military intervention abroad … earned him the sobriquet ‘the senator from the Pentagon….'”

–Jim Garrison, On the Trail of the Assassins

There is more to the ‘spark’ than that meets the eye. The late Avro Manhattan revealed it all in his book, ‘Vietnam:Why Did We Go’ which is available on line here:

http://www.reformation.org/vietnam.html

Correct, Ngo Dinh Diem was taken from a New Jersey monastery to head the bogus South Vietnam government the US established in avoidance of the 1954 Geneva Conference to unify Vietnam.

Then came the stupid Vietnam War. Of the more than 3 million Americans who have served in the war, almost 58,000 are dead, and over 1,000 are missing in action. Some 150,000 Americans were seriously wounded. Millions of Vietnamese were killed and injured.

The US has done a similar thing in Korea, not yet including a follow-on war nor murder of a South Korean president. Stay tuned.

Disclaimer: I was in Saigon on Nov 1, 1963, but I had nothing to do with the US-abetted murder of Diem and his brother.

Bottom line: Why celebrate a crime?

Did you not know that Ngo Dinh Diem was taken from the US to Vietnam? From the beginning, the US brought Ngo Dinh Diem from the US to Vietnam and staged him into power. Ngo Dinh Diem may be the first president of the Republic of Vietnam, but the real founder of the Republic of Vietnam was the US.

Actually, the real founders of S. Vietnam were the French — the French installed Diem. Diem was a Catholic screwball who thought he could impose Christianity on a majority Buddhist society. As for who was responsible for Diem’s death, this follows in much the same vein as who was responsible for JFK’s death. Some say the CIA was responsible; others say the Kennedy administration was responsible — plausible dependability at every level.

The French created the State of Vietnam in 1948 (+/- 1 year) during the 9 years war between the French and Vietminh (1945-1954). The Republic of Vietnam was created in 1955 (+/- a year). The US turned Ngo Dinh Diem from a nobody to the president of the Republic of Vietnam within a short period of time. Bao Dai allowed Diem to be a PM because of his connection with the US. Without the US connection, Diem would be a nobody living in the United States.

When the French lost in 1954, there was a Geneva Agreements (1954) to create a temporary line at the 17th parallel that created the North/South Vietnam. It was a temporary line awaiting for the 1956 election. Since the election did not take place, the 17th parallel was no longer valid. There are sources out there that say the Republic of Vietnam was a regime, not a State. It was not like the North vs the South, but the North (NVA) and South (NLF) versus the Republic of Vietnam’s regime. The Republic of Vietnam had control of one-two cities, and the National Liberation Front (NFL) had control of the country sides.

Ngo Dinh Diem was the Prime Minister of Emperor Bao Dai. He was appointed in 1933 with the title of Minister of Personnel but resigned shortly to protest the way French running Vietnam government. He was appointed again in 1954. However, Bao Dai and Ngo Dinh Diem had a major conflict of who would be the head of police force in South Vietnam. Even there were many attacks caused by the police force royal to the French government. Because of that conflict, a referendum to choose between Bao Dai or Ngo Dinh Diem was created by a united front of South Vietnamese scholars and activists. Ngo Dinh Diem won the majority so the Republic of Vietnam was established.