Christians celebrate Jesus’s birth and the immediate events around his crucifixion, but less attention is given to the clearest sign of his political activism, his overturning of the money-changing tables at the Temple in Jerusalem, the likeliest reason for his execution, as Mark Manolopoulos explains.

By Mark Manolopoulos

All four Gospels recall what is euphemistically known as the “Temple Cleansing”: an outraged Jesus overturns the tables of the money-changers. This story has always fascinated me even when I was an unbeliever, even whenever I am an unbeliever. I expect it has a lot to do with the fact that it contrasts sharply with the gentle and peace-loving Jesus, the hippie Christ.

But very recently this classic tale has become particularly poignant, with a renewed relevance and resonance. This article hopes to go some way in explaining why. I proceed by exploring a series of questions.

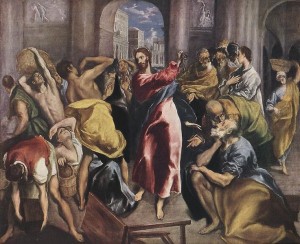

Jesus driving the money-changers from the Temple in Jerusalem, as depicted by the artist El Greco. (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

First question: did the Temple event actually happen? Answer: who knows? If we’re really honest with ourselves, we can’t even be really sure whether Jesus existed, let alone whether this “incident” happened.

His existence and this particular outburst are certainly possibilities, certainly reasonable possibilities and, today, we are surely open-minded enough to make room for the possible (which may even include the unlikely); in other words, we should no longer privilege the actual over the possible. And so, I myself can’t think of any reason why this Christic outburst couldn’t have happened, or why it wasn’t at least possible. …

Second question: what was the Temple? … In order to get to the crux of the meaning of the table-overturning, we must first determine the significance of its physical context which means determining the Temple’s meaning/s, its function/s, its effects.

For assistance, I turn to William R. Herzog II, Professor of New Testament Interpretation at the Andover Newton Theological School in Massachusetts, and the author of three cutting-edge books. … What does Herzog say about the Temple?

Drawing on a range of scholarly and biblical sources, Herzog proposes that, with the technological advances in ancient agrarian societies (the plow, draft animals, etc.), came surplus yields, and the temple became a sneaky and seductive way for rulers to extract this additional output from the peasant base, i.e. workers would hand over their hard-earned surplus-produce to the temple for the purported sake of pleasing or appeasing the gods.

And this process was couched in properly religious terms indebtedness to Yahweh with its attendant sacrificing and taxing even if the burden was economically crushing. Sneaky and seductive, indeed.

Howard Bess, a retired Alaskan preacher who draws on the work of Herzog (and whose article inspired this paper), expresses the nature and role of the Temple in suitably acute terms: “The Temple had become a lot more than a religious temple. It had become a tax collection agency and a bank. With that fat treasury, the Temple had entered the banking business and regularly made loans, primarily to poor people. Poor people were the victims not only of a flat tax, but also high-interest loans.” [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Would Jesus Join the Occupy Protests?”] Sounds familiar, no?

Now, I’m not sure I would want to reduce the Temple to strictly an economic-political device for exploitation can’t we maintain the ostensibly naive possibility that the Temple was “originally” a place of worship? Both Herzog and Bess state that the Temple “had become” an “oppressive institution.” So maybe it devolved into this site of subjugation. …

Whatever the case may have been back then, today we should at least consider the “suspicious-materialist” reading of the Temple: in other words, we should be open to the possibility that it was more than and otherwise than a center of worship, that it was (also) a site of economic oppression.

Third question: what was Jesus doing in the Temple? Answer: there’s obviously a range of possible answers. The predominant interpretation, the one advanced by the likes of Joseph Fitzmyer, … is that the table-overturning event was some kind of cleansing, some kind of purging of the Temple’s commercial activity.

Herzog argues that such a reading relies on the modern dichotomy between inner, “true” religion and a religiosity that focuses on externalities, including the act of sacrifice. Herzog explains: “The offering of sacrifices was at the heart of what the temple was about, and that included all of the support services required to maintain the sacrificial system.”

And so, the argument goes that Jesus wasn’t pissed off with the commercial activity that was going on, nor do we possess any evidence that those involved in this activity were abusing this system.

Having thus discounted these and other possible readings, and having already explained how the Temple was an instrument of exploitation, Herzog raises the possibility of an economic-political reading.

Pointing out that such an interpretation has existed since the time of Reimarus (the 18th Century), Herzog explains: “The temple cleansing cannot be divorced from the role of the temple as a bank. … The temple was, therefore, at the very heart of the system of economic exploitation.”

And to what/whom does the “den of bandits” refer? Herzog proposes a reversal: not those plundering outlaws who lived in caves, but the chief priests. Herzog surmises: “Jesus’ action in the temple, then, was not a cleansing of the temple but an enacted parable or prophetic sign of God’s judgment on it and, therefore, of its impending destruction. … The destruction of the oppressive institution that the temple had become was one step toward the coming justice of the reign of God.”

In sum: “Jesus attacked the temple system itself,” assailing it because it was patently unjust.

Now, given that I’m no scriptural specialist, I can’t say with any authority that Herzog’s reading is “The Correct One,” and I can’t say with any certainty to what extent his argument is compelling. But it appears to be soundly argued, given the biblical, historical, and logical-deductive groundings of his argument, Herzog certainly provides a rigorous, convincing case; consequently, we should at least seriously consider this interpretation.

But you may rightly ask if we aren’t even sure whether the table-overturning event happened or whether Jesus even existed, and if we acknowledge that the radical economic-political interpretation may perhaps be one interpretation amongst others, why am I so drawn to this particular story and this particular reading? This is our fourth question.

Fourth Question: Why am I So Drawn to this Story? I would like to believe that the Nazarene existed and that this event happened, but whether they did/did not isn’t my primary concern, or perhaps not my most primary concern right now.

My most primary concern right now actually involves three parts, each inter-related division corresponding to description, analysis, and prescription. My most primary concern right now is: (1) the increasingly disfigured state of the planet and its inhabitants (human and otherwise), exemplified by the financial, ecological, ethical, and other crises; (2) the ways in which capitalism (and its collaborating power structures, including “democracy”) fundamentally drives (and accelerates) this disfiguration by overtly and covertly exploiting the human and non-human masses, as well as the mass that we call “Earth”; and (3) (i.e. the third part of my most primary concern) is how on Earth we can save humanity and the Earth, which, going by the scale of the destruction and subjugation, surely involves radical transformation or to use an old and bloody word revolution.

Given this obscene state of affairs, a story like the Temple event rendered in its radical economic-political configuration is incredibly relevant on so many levels: it is a powerful. inspiring story about an individual who opposes an oppressive Temple system, whose modern corollary is capitalism, which extracts everything (and more) from the world.

The table-overturning story is powerful because an apparently powerless person rallies against the powerful. Little wonder, then, that as someone belonging to a multitude that is powerless and faithful, I am drawn to narratives such as this one. I am drawn to this narrative, drawn to its ethico-political significance for us today. I single out this biblical story/event for its applicability today, for its liberatory potential, for its emancipatory hope for here is a tale/praxis that inspires as much as it perplexes.

Others concur that this ancient tale is incredibly relevant today. Returning to Howard Bess: he refers to this story/act in addressing the initially-curious but ultimately-legitimate question, “Would Jesus Join the Occupy Protests?” to which he replies with a rigorous and resounding yes.

I will not rehearse his argument here, which already permeates the present one, and I think we can already perceive how this narrative can be easily transposed to the present day, whereby Jesus would participate in the movement against the Temple of Capitalism, whose Temple of Temples is Wall Street.

Indeed, I would even posit that the Nazarene would not only be involved in the Occupy Protests, but that he would be devoted to the task of the revolutionary overthrow of oppressive institutions, systems, empires (a task whose infancy is barely perceptible).

After all, arguments such as Herzog’s (and other brave and perceptive scholars like Bess) provide intellectual clout to the perhaps-initially-ridiculous-seeming notion that the character of Jesus is in some way driven politically “as well as” theologically, which is all very possible/probable, given that the political and the theological are and/or should be inextricably intertwined.

Radical readings like Herzog’s therefore lend weight to the possibility of Jesus as some kind of freedom fighter. Hence, this figure of the Christ is so very relevant, so very crucial for our times, given that we are reaching/have surpassed economic, ecological, and other tipping points. For here is a figure who protests against oppression, who is on the side of the poor, who stands up for them by standing up to the authorities, by committing the ethically violent act of overturning Temple tables, and who eventually dies for this standing-up-for and standing-up-to.

Now, let us quickly and briefly move our focus from what Jesus did and would do, to what his followers should do. After all, shouldn’t an understanding of the radical Christ be of consequence to the billions that identify as ‘Christian’?

After all, if true Christians are, by definition, those who are devoted to following and imitating the Nazarene, then true Christians would feel compelled to be integrally involved in the coming revolution.

And, yes, such a communistic imitation has historical precedents e.g. The German Peasants’ War of 1524-1526, England’s True Levellers movement in the 17th Century, etc., as well as much literature and revolutionary Christian writings (exemplified by liberation theology), a socio-textual history “beginning” with the communistic living of early Christians cited in the Book of Acts 4:32, 34:

“Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common” and “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold.”

I am, then, drawn to the possibility that this ancient tale/event might motivate those of us who are motivated by Christ, by those of us who “believe in him” in some sense, by those who attempt to live by his example, more or less. I am drawn to the possibility that this evocative story will help stir revolutionary desire, will inspire Christic-Marxist praxis.

Such a story is a tale worth re-visiting, re-investing it with what appears to be its originary ethico-political power, and re-telling it, hopefully unsettling our zombie-like apathy. To be sure, one story won’t make the revolution, but surely inspirational myths and speeches and images are often/always part of the mix. And so, it is little wonder that I am so drawn to this divinely violent Gospel story, signalling the good news of revolution.

Dr. Mark Manolopoulos is associated with the School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies at Monash University, which is based in Australia. This article is adapted from a paper that he presented to the Bible and Critical Theory Seminar in New Zealand.

It is often forgotten that in the Ancient world, temples served as state central banks. There the nation’s bullion reserves were stored and the national coins were minted, under the protection of the presiding deity. In Jesus’ time the temple at Jerusalem was a complex of buildings that covered seventy-five acres, more than six times the size of the entire city in Solomon’s era. Its mint had been turning out coins since the reigns of the Hasmonaean Kings, over 125 years earlier, and was in full production in Jesus’ time of small bronze coins called “Prutoth” bearing the name of the Emperor Tiberius and issued under the authority of his Prefect Pontius Pilate. With its great riches, the temple was guarded by a two thousand man Jewish police force and a full cohort (600 men) of the occupying Roman legion, who were quartered nearby in Fortress Antonia, built into the city wall.

It seems possible that the story of Jesus driving the “money-changers†out of the Temple is a fragment of folk memory of what actually happened that Passover – an armed assault on the very heart of the power of the state. These “money-changers” with their heaping tables of gold, silver, and bronze coins were not for a moment left unguarded by the Temple Police. While every man in Judaea carried a short dagger for personal protection in those times, the Gospels specifically state that Jesus’ men were armed with swords – exclusively military-grade weapons. This would also explainswhy Jesus suffered crucifixion, a particularly gruesome form of capital punishment reserved under Roman law only for non-citizens convicted of capital murder – or crimes against the state.

Unfortunately this theory fails in that the Romans executed only Jesus, and none of his followers. Their policy of ruthless extermination of anyone even remotely threatening to their power undermines this interpretation pretty decisively.

It is also interesting to note that in spite of the Jewish ban on producing “graven imagesâ€, recent evidence suggests that Temple mint was turning out silver Shekels adorned with the portrait of the Phoenician deity Melkart. These coins, originally minted in Tyre, are known to have been the only silver accepted for the annual Temple tax. Their silver content was reduced when the Romans took over, which motivated the local Judaean mintage. Perhaps Jesus’ protest was against blasphemous “money coiners” rather than “money changers.”

Whether parable or not, I’ve always viewed Christ’s overturning of the tables at the temple as His way of expressing the necessity of the separation of church and state.

It seems odd that people are coming around to read this stuff they abhor when they know what it is about before they come. Atheism and disdain for religion really don’t need apologists. Careful as Dr. Manolopaulos is in traipsing around any confession of belief in God, he must have stepped over the line somewhere. I don’t see where. There is a woman in my community who constantly harasses the Superintendant of Schools, insisting that no mention of religion should even be whispered in public school. Teaching history without mentioning religion is like teaching science without mentioning evolution. I personally like this stuff, and I read Bess’s articles often. Can’t we have a little fun thinking about this stuff without lots of hectoring by people who have no interest in the subject?

Jesus, Hymens & Aliens Â

youtube.com/watch?v=Qc7GRZ_4t-U

Let’s not find ourselves straying too far off the point about the Temple and the symbolic challenge it represented. Jesus did say give to Caesar what is his and give to Me what is mine. Accumulated stores of anything, no matter what shape the prized article assumed such as precious metals, food, animals and so on, were more than just distractions to the adoration of the Father. The money changers, their worldly preoccupations and where they chose to exhibit their contemptible belief system, incited Jesus into an angry outburst. For example, their persistent beliefs that required electing kings, issuing taxes, standing armies and so on. The willful act of bringing their unholy assembly into the Temple, and blatantly supplanting what God promised to do for his flock, namely to feed, cloth and protect his people was just too much for Jesus to bear. This was an ongoing spiritual error found in the hearts of the Israelites throughout the course of their exodus and conquests and it persisted long after their arrival into the promised land. The question is not what political systems, the ways to conduct enterprise, or what social structure we choose but how the people and their government work to prioritize the value of these things with a goal in mind to please, and not provoke the Almighty.

Remember the context of Jesus’ comment. A more appropriate reading rests on this analogy: imagine that the United States had been defeated in World War II and ever since had been suffering under the despotic heel of Nazi occupation. A fundamentalist preacher appears, attracts a great following, and is shown a German Reichsmark coin with Hitler’s portrait on it – would there be any question in anyone’s mind what action “Render unto Hitler what is due to Hitler†would actually propose?

This is what Jesus’ words meant to ancient Judeans – a call to the removal of an evil government and the restoration of the nation’s freedom, the “Kingdom of God.â€

By the way, the coin is this story is generally thought to be a denarius of Emperor Tiberius. You can see an image of it at http://cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=179249

Alternately, the period coin most often found in Middle Eastern excavations is this denarius of Augustus, Tiberius’ predecessor, which is viewable at http://cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=22248

A few points of clarification for historicVS. The Roman coin was considered property of the king during this period. Thus, giving the emperor his due and God what is his, did stray off from my point a bit, since only the Tyrian half-shekel was permitted in the Temple. Jesus’ comment is less about loyalties to church and state and more about Rome s insignificant power when compared to God’s kingdom. This is dramatized by Jesus using a whip, a symbol of authority as opposed to a goad for animal removal. Having a coin of the census implied an implicit recognition of the emperors sovereignty over the money changers and temple merchants. In any case, holy ground should not have been a gathering of activities that showed loyalty to civil authority, even though this need not contradict the person’s obedience to God.

Prof Bart Ehrman tells a different story. The money changers (not lenders) and animal sellers were essential to Jewish pilgrims travelling to the temple. Jews had to make animal sacrifices at the temple, nowhere else. But no way were pilgrims travelling from far away going to carry their sacrificial animals with them, when they could just buy them locally when they arrived. This raised a new problem, they only had currency marked with the image of roman emperors, ie. the occupiers, not to mention they claimed semi-divine status, making the coins profane. So they had to change the coins for temple currency before buying the sacrificial animal.

Summing up, Jesus interfered with Jews going about their essential worship, which you could argue was very inconsiderate and thuggish. Ehrman goes on to say perhaps his motivation (which we can only guess at) was to show people forcefully that the kingdom was coming, and with it a great destruction.

I’m impressed by the commentary of Ehrman and also Dale Martin because they don’t just make stuff up, they look at as much evidence as they can find, be it archaeological, Roman (and other) written records, and the bible text – carefully taking into account contradictions, chronology etc. When they do speculate without any evidence they are very clear about it.

During the time of Jesus there were thousands of people

crucified by the Roman occupiers. This was a highly visible demonstration of their power. The symbolism was added later by the writers of the gospels.

@ Hillary

I see conspiracy. I see A) the conspiracy to distract from the things Jesus *actually* did with attributes lifted from previous myths as you state… but furthermore, I see B) the conspiracy to further hide his actions by denying that he ever existed at all.

I’m not going to tell you he’s the son of God or anything like that (because the existence of God is unlikely.) But was he completely contradicting the system – and the system likes to crush things that rebel… and when those rebellions continue after their death? If you can’t beat’em, join’em… then move everything back to how it was before, but with different names.

Thank you for trying to keep Drs. Bess, Herzog, Jesus, and yourself alive in the allegorical romance of religion as an independent function of human behavior control.

It feels good, but it has no basis in fact or relevance. Religion is a political means of population control. It relies on the fact that we are evolved as members of a herd with the instincts for survival subject to herd decisions. We trust our feelings and our emotions. We feel right about the habits we accept through our perceptions, our feelings and emotions.

We resist contrary ideas based on logic. We deny conclusions contrary to our beliefs.

You or I could begin a religion or a political movement with the most far fetched theory and gain up to 20% of any population over time by repeating the mantra of that theory while it is ignored by the rest of the population.

The reason is simple and organic. People trust the early limbic brain more than the modern cerebral cortex. The necessity for behavior control is a necessary requirement for family and group survival. The downside is that such needs become beliefs and the beliefs become the means for certainty. The result is bigotry. All political-religious organizations require that their belief is superior to all others. Every ancient city state walled itself off from its neighbors by responding to the universal neurological conflict between perception and reason.

Every prophet expressed the same ideas in the way his audience understood him. Every follower reinterpreted these ideas as they applied to the values of society. Every religious-political organization evolved to be more inclusive as societies changed. Jesus is a typical prophet form, no different than Moses, Muhammad, Buddha, Zoroaster, or Genghis Khan.

I don’t come here to be exposed to religious indoctrination and Christian propaganda. It’s one thing to be neoliberal apologists. It’s quite another to exploit any credentials you might possess as journalists to promote Christian evangelicalism.

You press the limits of credibility with one, completely destroy it with the other.

This piece may be of interest to “Bible scholars” where it should be confined.

“inspirational myths and speeches and images are often/always part of the mix”

.

Mark Manolopoulos likes that mix of gobldy gook from the Judeo/Christian Bible.

.

Perhaps it is yet another subtle “spreading the God word” attempt.

.

“Greatest Story Ever Sold” the collection of myths basically plagiarized from previous myths.

.

http://www.jesusneverexisted.com/glory.html

Religion continues to have the greatest influence in human behavior. Understanding why and how is more important than expressing a belief that it doesn’t exist.