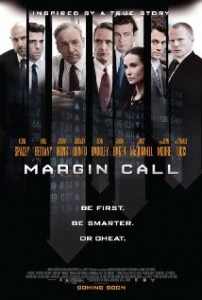

Wall Street has created a “moral” universe that elevates short-term profits into the ultimate “good,” rewarding those who can achieve them with massive bonuses. The movie Margin Call follows these players when their universe collapses, writes Lisa Pease.

By Lisa Pease

What would you do if you had knowledge of an imminent catastrophe that you had no power to stop? That was the question that inspired the new film “Margin Call” from writer/director J.C. Chandor.

Based on the financial crisis of 2008, the film is a tightly paced, highly suspenseful look at the first 36 hours of a meltdown from the viewpoint of a few key people in a Lehman Brothers-like investment firm. The damage has already been done, and there’s no way to reverse it. The characters are faced with Hobson’s choices that leave little room for moral concerns.

Indeed, that’s the fascination with the film. While some have decried the film, claiming that it tries to make the Wall Street crooks who stole our money sympathetic characters, that’s not what I saw at all. I had no sympathy for any of them, but I found them fascinating, nonetheless.

Here are a group of people who have uncritically bought into a way-of-life destined for failure, and suddenly that failure is upon them. How will they deal? What will they do? What can they do?

During the course of the escalating-by-the-minute meltdown they are facing, each character finds out, in his or her own way, what they are — and are not — made of.

The story opens with the layoffs of a large number of people in the firm. It’s a scene that unnervingly takes us all back to those first few weeks after the financial crisis, for surely if we weren’t laid off, we knew others who were.

When Eric Dale (Stanley Tucci), a 19-year veteran of the firm, is laid off (with a paltry six-month’s severance for those 19 years), he leaves a warning and a thumb drive of data with one of his junior associates and warns him to “be careful.”

Something is terribly wrong, and Eric hasn’t quite figured it out yet.

His bright younger associate Peter Sullivan (Zachary Quinto) pulls up the model, tweaks a few numbers, and suddenly sees the future is already the present, and it looks bad from every angle. One by one, superiors are brought in to deal with the crisis, played by actors Paul Bettany, Kevin Spacey, Demi Moore, Simon Baker, and ultimately Jeremy Irons.

You know these people. You’ve worked with some of them. In a few broad strokes, you see the uptight manager, the handsome if shallow braniac, the quiet genius, the get-by-on-his-charm kid, the company man, the disconnected man at the top who readily admits he didn’t get there because of his brains, and more.

That the characters seem so specific despite the lack of background data in the script is a tribute to the talents of the actors involved (i.e., some brilliant casting).

I think we all want to better understand what happened. How could the system get so broken so quickly? In that sense, the movie offers little direct information. This is not history or documentary.

What this is, however, is sheer drama. I truly felt glued to the screen. My thoughts never wandered, a rarity in the movie theater these days. I really wanted to know, at every second, what would happen next. Of course, we all know what happens, eventually. But watching these people in this moment was incredibly compelling.

Kevin Spacey is particularly interesting as Sam Rogers, the head of the trading group that is going to have to do the most to deal with the coming crisis. He’s torn by the results of past choices that leave him only two completely wrong courses to choose from. We learn over the course of the film just how much his devotion has cost him.

I felt it was an accurate depiction of the mindset not only within that community but many others. Choices are made based on what’s profitable today or tomorrow and rarely with an eye to what will be best in the long-term.

After viewing the film, I was reminded of Jared Diamond’s book Collapse, in which he demonstrates that short-term thinking and, particularly, cultures in which the elite separate themselves too far from the working class, lead inevitably to disaster and collapse of any given society.

The real issue is not how to deal with crises as they arise, but to see them coming and change course early enough to entirely avert them. When the elite are more closely tied to the workers, they feel the pain sooner and make appropriate course corrections. The further, however, the elite get from the workers, the more insulated they are, preventing them from seeing genuine problems until it’s too late to solve them.

I couldn’t help but think of climate change deniers, and the unhelpful choices we, too, will face if we don’t change our ways while there is still time. If we wait until the catastrophe is acknowledged and apparent, as these characters did, it will already be too late.

And the choices are the same at the personal level. By pursuing a certain way- of-life, are we alienating those we’re going to need later? By accumulating money, are we guaranteeing our future happiness? What else should we be pursuing?

“Margin Call” may infuriate you all over again, but it will also remind you of how important our current decisions are now. We still have lots of time to prevent future crises, if we look a little further down the road and give up some short-term wants for some longer-term needs.

Lisa Pease is a writer who has examined issues ranging from the Kennedy assassination to voting irregularities in recent U.S. elections.

And to ouidiva, I didn’t have that hyphenated in the original. The editor did that, and many of the other things you have pointed out in other posts.

No offense, Ms Pease, but I don’t think the problem was an inability in “seeing genuine problems until it’s too late to solve them.” Sure, some upper-level people may have been caught in the middle in the collapse, but many more knew what they were doing and were well set up to make out no matter what. They had the bailout card to play, and they had schemes in place to cash out when things went south. The game was rigged, heads they win tails we lose and they made money during the collapse because they made damned sure they had contingencies in place.

They didn’t fail to see the problem, they didn’t see it AS a problem. Just the price of doing business. Privatize the gains, socialize the losses. Do some spin and damage control, pretend to be sorry, pretend they fixed it, and then gear up for the next phase of business. Like high-rolling thieves and con men, they’ll just move from hit job to hit job until they’re stopped or there’s nothing left to steal. And what happens to their victims is not part of the calculations.

In this case, you have attributed to incompetence what is clearly malice.

DarthMeow (and I love that name), I don’t take offense. You make a good point. At least some knew the whole thing was a game and rigged in their favor. Of course, I think many more didn’t know and didn’t care. And sadly, the rest of us have had to pay, no matter what.

Wall Street has been mandating short term goals for 45+ years. Everything is geared to the short term so if needed to make the dollar and percentage report look good, sell the assets off, do whatever it takes. We will think of something else next quarter to look good. It works for a while but eventually there will be nothing left to do and the entity will fail, AKA 2007/8.

Interesting review. One point, perhaps picky, but humor me: Find an English class and learn how to use a hyphen. “Way of life” should not have been hyphenated in your context. Neither should “in the long term” as you used it.