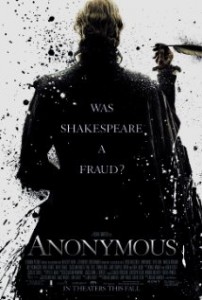

Perhaps unavoidably, history is filled with mysteries, both recent and in the distant past. A great example of this fact in the literary world has revolved around the actual authorship of Shakespeare’s plays, a topic that has been fictionalized into the new movie Anonymous, as Lisa Pease explains.

By Lisa Pease

The film Anonymous deals with a longstanding debate many people have never heard about: the question of who wrote the plays of William Shakespeare. While the answer seems obvious, numerous scholars have concluded the answer is anything but.

Some of the many notables who have challenged the notion that the barely educated Shakespeare wrote those brilliant works, filled with literary and cultural allusions, include Sigmund Freud, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), Charlie Chaplin, Orson Wells, famed Shakespearean actor Derek Jacobi, Malcolm X, Helen Keller, James Joyce, and Lewis Lapham, among others.

Some of the issues raised include these: Shakespeare’s plays display a vast and in-depth array of learning that his grade-school education could not have provided. Fourteen of Shakespeare’s plays take place in Italy, but William Shakespeare never went to Italy. Most of his plays deal with the intrigues of the nobles, but Shakespeare was a commoner.

In addition, not a single document has ever surfaced written in Shakespeare’s own hand, an oddity shared only by his contemporary Christopher Marlowe, who some have speculated wrote Shakespeare’s plays after faking his own death. Yet numerous handwriting samples exist for many of their lesser-known contemporaries.

Early theorists thought perhaps the learned Sir Francis Bacon or poet Ben Johnson might have written the works under the name of Will Shakespeare. One late 19th century theory posited that the name Shakespeare was used for a collective of writers that included Marlowe, Bacon, and others.

Another theory favored around the turn of the previous century was that William Stanley, the Sixth Earl of Derby, wrote the Bard’s words.

The theory the movie is based on, however, is one of the current mainstream theories regarding the authorship question.

In 1920, an English schoolmaster named John Looney set out to try to uncover Shakespeare’s true identity. He made lists of allusions and references in Shakespeare’s work and then tried to map them to one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. He found a remarkable fit in the Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere.

De Vere had been a child prodigy who developed a serious interest in the arts and wrote several poems under his own name. He attended college and was surrounded by a bevy of tutors. He lived inside the Court bubble for a good portion of his life, and saw the intrigues of the nobles up close.

He lived in Italy for two years. He was stationed in Scotland for a couple of years. He studied law at a place known for mounting dramatic productions. And on and on.

Naturally, there are rebuttals to these theories. While the dating of Shakespeare plays is an inexact science overall, those who think Shakespeare wrote his own plays have a strong argument in The Tempest, which seems to be based in part on a famous shipwreck that happened after de Vere died.

The film will not decide the issue for you. It simply presents its own theory, fictionalized, of course, of what might have happened.

The film is bookended by a contemporary device, reminding the audience that what follows is itself a play, a story, and not history or documentary. And with that context firmly in place, the wild ride through Elizabethan history, arts and politics, and the intersection thereof, begins.

The story shifts back and forth between the older de Vere and his younger self, with key points in his life and English history highlighted. The story is breathtaking in its intricacy, a delicious, hearty meal of Elizabethan era intrigue.

The story centers around the period where Queen Elizabeth was nearing the end of her life and the question of succession was on everyone’s mind. But the tangled history of Britain’s monarchy provided no easy answers. Add to this mix a few more theories about incest and secret descendants and you have a storyline that roils like a witch’s brew.

Although the film is graced with the talented Rhys Ifands as Edward de Vere, Vanessa Redgrave as the so-called “Virgin Queen” and Edward Hogg as the Queen’s trusted advisor Robert Cecil, among others, the real star of this film is the story.

Billed as a “political thriller,” it’s an adventure in alternative history one won’t soon forget. Check your skepticism at the door, and open your mind to a fascinating tale of Shakespearean proportions.

The film also celebrates the sheer force of words from both a positive and negative point. Words can be used to sway populations and even royals to action. Words can also be used to malign and betray.

Those who wield words well have tremendous advantage, then and now, as the film itself demonstrates. The people I saw the film with were mostly unfamiliar with the authorship controversy. On the way out, many expressed a newfound curiosity about the matter.

Lastly, the film is both an homage to and a warning about following one’s passions. In the end, our passions define us, for better and for worse.

As a postscript, V for Vendetta fans might note that the Gunpowder plot of the “Remember, Remember the Fifth of November” rhyme happened just four years after these events and contained some of the participants from the Essex Rebellion, a key event in Anonymous. The plot was foiled by the same Robert Cecil, reminding us that history is one long through-line, no matter where you enter it.

Lisa Pease is a writer who has examined issues ranging from the Kennedy assassination to voting irregularities in recent U.S. elections.

The Shakespeare plays we know are unlikely to be exactly what Shakespeare wrote. The thing is that they were not collected in print till a hundred and more years after he died. Just like today, i bet they were tuned to be more popular at the time they were preformed. Shakespeare’s plays must be like the bible, who knows for sure what he wrote. Einstein’s educational record was remarkable. There is a willful misunderstanding of how his schools graded. His major early work on the special theory of relativity was done while he was employed as a junior clerk at the Swiss patent office in 1905. His patent office job was understanding the top science of the day and was made for him by the government, so he had time and money to think.

There is another possible author of Wm Shakespeare’s plays. In some ways it would be odd for another man to have written Shakespeare’s and choose to remain not only anonymous but undetectable. Men are proud of status, want recognition and praise, and, as often as not, take others’ achievements as their own. Why would the true author want to remain so unknown and unrecognized? Because, perhaps, of the scandal. In Elizabethan England, WOMEN were not allowed to write plays for the public theater. The most likely woman was Mary Sidney Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke. She was born 3 years before Shakespeare and died 5 years after. She developed and led the most important literary circle in England for 20 years. She was devoted to great literature and strove to create a strong literary tradition in English – which was regarded in that time as a rather provincial language limited to a small number of people. She was one of the most educated, politically and socially active women in England, comparable only to Queen Elizabeth. More interestingly, her love life parallels the details of Shakespeare’s sonnets. In another curious incident, Ben Johnson, (one of her proteges and a close friend to her oldest son), wrote a eulogy in the First Folio “to the memory of my beloved, the author” two years after her death. (“Beloved?”) Also, the First Folio is dedicated to her two sons, neither of whom has any known connection to William Shakespeare of Stratford. It is possible that her elder son, William, was the only one who knew she was the real “Shakespeare” and saw to the publication of her work. As a close friend, he may have shared the secret with Johnson. If only these two knew the facts and kept them hidden, there would have been few rumors or obvious hints to survive the centuries since to clear up the mystery.

There have been quite a few prodegies that have come from humble beginnings. To say that the Stratford man could not have been one is as credable as the earth is flat, or Collumbus discovered America!

I’ve found that very few people can discuss this topic with any objectivity or critical intelligence. Some of the most learned and intelligent people I know start spluttering invectives and tossing insults if it comes up. So don’t suppose this is one of those far-off metaphysical possibilities that gentle minds can ponder in serene, lofty contemplation.

Far from it. No, this is going to be a knife fight – centuries of academic pedantry and the careers of sacred-cow ‘experts’ at the highest levels of the academy are hanging in the balance, and believe me, they will go down swinging. Leading the charge is James Shapiro’s ugly, distorted and intellectually dishonest op-ed piece in the New York Times (Oct. 16, 2011).

But Shapiro – with two books and his reputation as a Shakespeare scholar to defend – comes off as just another puffed-up academic bully headed for the dustbin of history. It’s actually going to be fun watching the gasbags in the field inflate, whine and then pop, and there will be many, many who will.

Because when you step back from it, Wm Shaksper of Stratford was a nobody, a nothing, a nonentity who could not and did not write, as far as anyone can tell, anything. Wm. Shaksper, grain dealer, perhaps could not even read, either, since he apparently he had difficulty spelling his name – his half-dozen signatures, all spelled differently, being the only evidence of any written legacy at all. His father was illiterate and so was his daughter.

So of course, there is no evidence of any literary interest, talent, or activity.

The name Shake-Speare which appeared on early quartos and then on the sonnets published in 1609 is, in fact, a pseudonym and a joke: the hyphen gives it away, while the term itself is a mildly obscene Elizabethan pun which contemporary Brits might translate ‘wanker.’ (Falstaff is another one…)

Beyond that, Shaksper had never been to Italy, had no clue about the Elizabethan court, could have had no access to works which several plays are based upon.

Even if you assume “genius” (a crassly abused term, used to justify fantasy in this argument) the author still had to acquire knowledge, since even geniuses aren’t born with it. Somehow, the acquisition of vast knowledge, vocabulary and expertise in a half-dozen fields plus literary sophistication in several languages has to be explained. But there’s no evidence that Mr. Shaksper even attended grammar school, let alone any university, whose level of education the Shakespeare plays reflect.

None of this matters to academics who, like Shapiro, have made careers out of inflating a vacuum, an invisible man, into dogmatic scripture.

If you want to read a lexicon of weasel-words, trapdoor language and qualifications in the conditional and the subjunctive, just consult Mr. Shapiro’s book, or the so-called biographies by Ackroyd and others. The literary heavyweights in the arena, Harold Bloom and Helen Vendler, are no better – Vendler’s nearly unreadable set of bloviations on the sonnets ignore the passionate, emotionally acute and even devastating human reality that the poems reflect, but what you will find is that these and all other “scholars” in the field will regard these intense documents, written with blood and fire, are all mere art-works, a demonstration of virtuosity with no important human story underlying them.

Same for the plays. Does any academic ask: Why would someone write these plays? Why did this author come again and again to the conflicts behind royal succession, looking at it from every angle? There is no answer from the Strafordians, and can be none.

On the other side, the answer in works like Charles Beauclerk’s “Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom” is so powerful that, considered merely in human terms, it becomes overwhelming as all the pieces fall into place. Speaking personally, the Tudor Prince theory – found in both this book and in Emmerich’s movie – is the key to unlocking the question posed here: if it’s true that the 17th Earl of Oxford had a stronger claim on the English throne than any other living person aside from Elizabeth herself, you can understand why he would use the theater to tell that hidden, forbidden truth, as making his claim in public would have been a clear act of treason – a crime punished by many executions in the era.

The good news is that human blood flows back into the Shakespeare canon and we can read and see the plays with a transformed vision – with a real man and a real artist behind them. The academics may hate this, but it’s a tremendous breakthrough and a gift for everyone else – we can finally understand what the world’s greatest writer was really saying, and why he was saying it.

That in itself is a cause for great celebration.

Albert Einstein did not come from a family of physicists. His early educational record was at most unremarkable. His major early work on the special theory of relativity was done while he was employed as a junior clerk at the Swiss patent office in 1905. How could someone of such humble origins produce the genius that is the root of modern Physics. Yet no one has suggested conspiracy theories of the originality of his works. Oh just a minute. About ten years ago there was compelling evidence that Mrs. Einstein was Einstein.

These conspiracy theories will never stop.

I read long ago that many of Shakespeare’s plays were adapted from Italian plays or literature, however those plays have been lost, but there are accounts of their existence. Shakespeare borrowed the plots and dialogue from these plays, but that does not mean he did not add his own originality to them. This may be the most likely explanation for the range and depth of his plays.

It is not merely that plays were set in Italy; the plays show an intimate knowledge of both geography and local custom which would have been unavailable to someone who had not visited Italy. Books were very hard to come by, and the writer of the works must have visited libraries if he had not had direct experience. Libraries of the time were a privilege of the wealthy and the aristocracy. There is no record of Stratford having visited libraries, but Edward de Vere resided in the house of William Cecil, and there and other places he had access to books and manuscripts that no commoner would have seen without leaving a record.

Indeed, the orthodox dating of Shakespeare’s plays is an “inexact science.” Thank you for noting it, Lisa Pease. Yet a wealth of evidence exists that helps date the plays. For example, Marlowe referred to a line in The Tempest in his poem, Hero and Leander. Marlowe died in 1593, so the play can be dated 1593 or before. But orthodoxy fixates on ca. 1610 for The Tempest’s composition because it is a late play, and circa 1593 is near the start of the Stratford Man’s supposed writing career. In the appendix of my new book, Shakespeare Suppressed, I list 92 more “too early” allusions to the Shakespeare plays (1562 to 1606).

Quote: “Some of the issues raised include these: Shakespeare’s plays display a vast and in-depth array of learning that his grade-school education could not have provided. Fourteen of Shakespeare’s plays take place in Italy, but William Shakespeare never went to Italy. Most of his plays deal with the intrigues of the nobles, but Shakespeare was a commoner.”

I’ve written stories about time travel, even though I’ve never traveled in time. I’ve also written about alien worlds, even though I’ve never been to one. The argument here is rather shaky.

And will your works be remembered 500 years from now? that’s really the point.

^My work might be remembered 500 years from now.

But conspiracy theorists will claim Al Gore wrote them. lol.

Choose your voice.

It makes one sound like a dickhead to have:

“you have a storyline ”

shortly followed by:

“one won’t soon forget.”

Don’t one?

Oh, please. This is nitpicking at its most annoying. “You” used in the non-specific sense and “one” are now used interchangeably.

Thanks for your comments, William. I have also read that some scholars date all of Shakespeare’s plays within de Vere’s lifetime. I love that people are still looking into this, so many years after the fact.

My compliments for a felicitous and non-partisan review. I would just like to say a few word regarding ‘The Tempest’ being used to conclusively prove that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, who died in 1604, could not have written a play that opened in 1611. Logically, plays are frequently written far in advance of their first performance. But specifically, I believe neither the Stratfordians nor the Oxfordians may lay total claim to ‘The Tempest’ as their candidates. According to the scholar Marie Merkel, there are extraordinary similarities between Ben Jonson’s characters and some in ‘The Tempest’. It is entirely possible Jonson finished the play to be included in the First Folio. Thus a topical reference to a shipwreck in Burmuda that happened after Oxford’s death could have been spliced into a play otherwise set very tracably in Vulcano, near Sicily, in the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, the prevailing interpretation is playing defense, not seeking the facts. with appreciation, William Ray wjray.net