From the Archive: In Argentina, a case of a 35-year-old woman may finally prove that military officers in the Dirty War of the 1970s had a systemic scheme for stealing babies from female dissidents who were murdered. In this 1997 article, Argentine journalist Marta Gurvich examined one of these shocking cases.

By Marta Gurvich

Pablo and Carolina, 19 and 21 respectively, were raised as brother and sister in a seemingly respectable Argentine family. With their father a doctor and their mother a teacher, the pair grew up in middle-class neighborhoods, attended good schools and wanted for little.

But now as young adults, Pablo and Carolina are caught up in one of the last active disputes of Argentina’s so-called Dirty War — and it is one that rips at the very heart of human relations. They find themselves in a legal battle over a terrible historical legacy in which their true identities play a central part, a murder mystery about the fate of their real mothers.

Pablo and Carolina, however, seem to sense that the truth could shatter any hopes of a normal life as well as their relationships with the couple that raised them, Norberto Atilio Bianco and Susana Wehrli.

While Pablo and Carolina remain in Paraguay out of the reach of Argentine law, Bianco and Wehrli have faced extradition to Argentina and are now imprisoned for kidnapping and suppression of their children’s true identities.

“I have no doubts that my real parents are the couple Bianco-Wehrli,” Pablo told a judge in Paraguay on May 10. “The only thing that I want is to continue with my life, with my parents, the Biancos, my wife and my daughter, and my sister.”

In another passionate statement, Carolina declared that all the family’s progress and education could be credited to the Biancos’s love and dedication.

When the two young adults refused to give blood samples for DNA testing sought by an Argentine court, a Paraguayan judge ruled there would be no compelled genetic testing. The Argentine judge Roberto Marquevich fumed, “I can only guess that perhaps there is a so-called loyalty in Paraguay towards those who were part of military governments in Latin America.”

Beyond establishing the parentage of Pablo and Carolina, the DNA tests could help clarify Dr. Bianco’s suspected role as an accomplice in the murders of his children’s real mothers and the deaths of many other pregnant women under his care.

Bianco, as a military doctor in the 1970s, is accused of collaborating in one of the Dirty War’s most gruesome practices: the harvesting of babies from women facing death for their suspected leftist political views.

Death Flights

According to testimony given to Argentina’s truth commission, Bianco oversaw nighttime Caesarian sections or induced early deliveries on women captives. A few minutes after the deliveries, Bianco pulled the babies away from sobbing mothers, according to witnesses who were at the Campo de Mayo military hospital.

Bianco then drove the women to a military airport. There, they were sedated, shackled together with other captives in groups of 30, and loaded onto a Hercules military cargo plane.

At about 11 p.m. at night, the plane flew out over the dark water of the Rio de la Plata or the Atlantic Ocean. According to the testimony, the new mothers and other victims were shoved into the water to drown.

Back at the hospital, witnesses said, some of the babies were dispatched to orphanages but most were divvied up among the Argentine military officers, especially those whose wives could not bear children. The babies sometimes arrived at their new homes wrapped in army coats.

During the Dirty War, which raged from the mid-1970s through the early 1980s, Argentina’s military “disappeared” thousands of Argentines, as many as 30,000, according to some human rights estimates.

Captives from all walks of life were systematically tortured, raped and murdered, sometimes drowned and other times buried in mass graves. After the military government collapsed in 1983, a truth commission began documenting the grisly events. But the mysteries of the missing babies were among the hardest to solve.

The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group formed in 1977 to search for these babies, estimated that as many as 500 infants were born in the detention camps. After years of detective work, the Grandmothers documented the identities of 256 missing babies.

Of those, however, only 56 children were ever located and seven of them had died. Aided by recent breakthroughs in genetic testing, the Grandmothers returned 31 of the children to their biological families. Thirteen were raised jointly by their adoptive and biological families, and six cases have been tied up in court custody battles.

But the Bianco criminal case gained public attention because an agronomist named Abel Madariaga has pressed a legal claim that his son may have been kidnapped by Bianco, who also allegedly participated in murdering the boy’s mother, Madariaga’s wife, Silvia Quintela. The Grandmothers have supported Madariaga’s efforts to solve the case.

A Missing Mother

The story of Madariaga’s lost son began more than two decades ago, on the morning of Jan. 17, 1977. Silvia Quintela, then 28 and four-months pregnant with her first child, was walking along Hipolito Irigoyen Street, a middle-class neighborhood in a suburb of Buenos Aires.

It was summer in South America and the slight brown-haired woman, a medical doctor by training, planned to meet a friend at a train station and then head downtown.

Like many other Argentines, Silvia Quintela was a Peronista, a follower of the populist military officer and political leader, Juan Peron. During her studies at the School of Medicine in Buenos Aires, Quintela and her husband had been members of the Juventud Peronista (the Peronist Youth).

As a surgeon, Silvia Quintela had treated the poor at a small clinic in the town of Beccar, near a shantytown called La Cava. She also was active in the province’s medical association.

In 1973, Peron won election as president, but his death the next year put his third wife, Isabel, in office. In 1976, with inflation running rampant and political turmoil spreading, the military seized power.

In secret, military death squads began rounding up and eliminating thousands of political opponents. A chilling new word entered the lexicon of repression: “the disappeared.”

Amnesty International verified some cases of illegal detentions and killings. But on Dec. 31, 1976, Henry Kissinger’s State Department assured Congress that “torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment have not been general practice in Argentina.”

Less than three weeks later, Silvia Quintela became one of the Army’s growing number of targets.

At about 9:30 a.m., Jan. 17, three Ford Falcons screeched to a stop around Quintela. Men in civilian clothes jumped out of the cars and grabbed her. They forced her into one of the Falcons and sped away.

That afternoon, seven men broke into the home of Silvia’s mother, Luisa Quintela. After tearing up the rooms, they told Mrs. Quintela that her daughter had been arrested.

Immediately, Luisa Quintela and Madariaga began searching for Silvia. But Madariaga’s life was in danger, too, so he fled Argentina, seeking political asylum in Brazil and later in Sweden. But wherever he went, Madariaga asked Argentines who had escaped the detention camps what they might know about Silvia.

Protesting the Horror

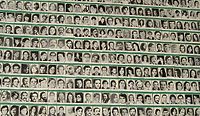

Back in Argentina, women whose sons and daughters had disappeared founded a group called Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, named after the plaza in front of the Pink House (the presidential offices). Each Thursday, the women would don white kerchiefs and march around the plaza carrying photos of their missing children.

Because of the number of pregnant women who had disappeared a second group was founded called Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. The Grandmothers looked for the babies in orphanages, examined records of adoptions and collected information from nurses and doctors who had treated the pregnant women and their babies.

As international concern mounted, Patricia Derian, President Jimmy Carter’s new assistant secretary of state for human rights, made the Argentine Dirty War one of her top causes. Though the Argentine military denounced Derian’s interference, the lives of some high-profile captives were spared.

But the Argentine military had U.S. allies, too, including Ronald Reagan, a Republican presidential aspirant who defended the generals. In one radio commentary, Reagan urged Derian to “walk a mile in the moccasins” of the Argentine officers before criticizing them.

After Reagan won the White House in 1980, he restored friendly ties with the generals. Reagan even authorized the CIA to collaborate with Argentine intelligence in training the Nicaraguan contra rebels in Honduras.

But the days of the dictatorship were numbered. In 1982, the British defeated Argentina in a war over the Falkland Islands and the disgraced military regime collapsed.

To resolve the cases of the “disappeared,” the new president Raul Alfonsin created a truth commission, known as CONADEP. Madariaga also returned to Argentina and searched for his wife. In the following months, the story of Silvia Quintela and her baby slowly came into focus.

Testifying before CONADEP, Beatriz Castiglione de Covarrubias, a survivor of the Campo de Mayo detention center, recognized a photo of Silvia Quintela and recalled that Quintela was held at the camp while her pregnancy progressed.

Juan Scarpetti, another Campo de Mayo survivor, reported that Quintela gave him medical treatment when he arrived unconscious. When he awoke, he recognized Quintela whom he had known when they were both members of the Juventad Peronista. Scarpetti testified that Quintela gave birth to a boy sometime during the second quarter of 1977, but he never saw her again.

Experimental Treatments

At the Campo de Mayo hospital, according to other witnesses, pregnant women were kept under guard and either blindfolded or forced to wear black sunglasses.

Even during labor, the women were tied hand and foot to their beds. Some were given experimental treatments to accelerate the births. Others were subjected to Caesarian sections. Witnesses identified Major Norberto Atilio Bianco as one of the doctors in charge.

Dr. Silvia Cecilia Bonsignore de Petrillo testified that on one Sunday in 1977, she was called in from home to perform an urgent Caesarian. When she arrived, she found soldiers patrolling the floor and Bianco in his military uniform.

Bianco ordered Bonsignore to operate on a pregnant woman he had brought to the hospital. Bonsignore recalled that the patient was a thin woman with dark hair.

“She cried inconsolably during the Caesarian,” said Bonsignore, who called the surgery “the bitterest moment” of her life. Bonsignore did not know the woman’s identity.

Another camp doctor, Jorge Comaleras, testified that Bianco was in charge of removing the mothers after they gave birth. Bianco took them in his own car, a Ford Falcon, Comaleras said.

The women were driven to the airfield at Campo de Mayo, where the Hercules cargo planes departed shortly before midnight. The planes headed toward the Atlantic and returned about an hour later empty.

Silvia Quintela apparently was put aboard one of the death flights, the Grandmothers concluded.

But the fate of Quintela’s son remained a mystery. Madariaga discovered that during the Dirty War, Bianco and his wife, Susana Wehrli, registered two children as their own: a girl, Carolina, in October 1976, and a boy, Pablo, on Sept. 1, 1977.

But no one had seen Wehrli pregnant and a friend recalled that Wehrli once confided that the babies were adopted. The birth certificates were purportedly signed by two doctors who worked with Bianco, but the courts concluded that the certificates were bogus.

Genetic Testing

Based on the testimony about Silvia Quintela giving birth to a son in the second quarter of 1977 and the Sept. 1 date on the boy’s birth certificate, Madariaga suspected that Pablo Bianco might be Silvia’s and his baby.

In the Argentine Federal Criminal Court, Madariaga accused Bianco of kidnapping. Madariaga demanded a genetic test of Pablo to determine the boy’s true identity.

In 1987, an Argentine judge ordered the Biancos’ arrest, but the couple had fled. After Bianco and his wife were located in Asuncion, Paraguay, the judge sought their extradition back to Argentina. But a Paraguayan judge blocked the transfer, leading to a prolonged legal battle while the Biancos lived under a form of house arrest in Asuncion.

When I reached Bianco by phone twice in Paraguay, he was eerily calm and polite, seemingly determined to present an image as a reasonable person.

“I won’t defend myself in the press,” the exiled doctor said, his voice under control. “I’ve presented my case to the courts. This is the position I’ve been holding in silence for many years and I won’t change now.”

Bianco insisted that he had always acted “in accordance with the Geneva Conventions for a military doctor in an anti-subversive war or in any other war.” He added obliquely: “Those of us who have acted in good faith are suffering this disgrace.”

Not wanting to sound “authoritarian,” Bianco asked that I voluntarily end our second conversation so that he would not be forced to hang up.

After their long-delayed extradition to Argentina, Bianco and Wehrli conceded in court that they were not the biological parents of Pablo and Carolina, but denied that they had kidnapped the children. The couple insisted that they had the consent of the biological mothers but the court record did not make clear who the mothers were or how the supposed permission was obtained.

To determine the real identity of the children, Judge Marquevich again urged Paraguay to conduct a genetic analysis on the two children. But Pablo and Carolina balked.

“I refuse to give a sample of my blood,” Pablo told the Paraguayan judge.

Carolina added, “Now that I’m a mother of two children I have understood that you have to leave the selfish behind. What the Grandmothers don’t understand is that what they are doing is characterized by hatred and selfishness. Their goal is to succeed in the legal claim, without noticing our fate.”

So the mystery continues. For Madariaga, who lost a wife in the Dirty War, there is only a distant hope that he might still find the son he never knew. “I would love to find him in Pablo,” Madariaga said. “But I cannot dream about it. The only way to know is through the genetic analysis.”

And that analysis, if it ever happens, still seems a long way off.

Update: Since Marta Gurvich’s article in 1997, the mystery has continued about who was the real mother of Pablo Bianco. However, a DNA test in 2010 concluded that a different kidnapped baby was Silvia Quintela’s son. It is believed that Pablo may have been the son of another woman, Beatriz Recchia, a friend of Silvia’s who was detained in the same time frame and who was four months pregnant at the time.

Show Comments