Special Report: Sixty-nine years ago, British commanders dispatched mostly Canadian troops on a raid against German coastal defenses at the French city of Dieppe. The attack was a fiasco, losing more than half the landing force, but well-connected British officers spun the defeat into a P.R. victory, writes Don North.

By Don North

In many World War II history books, the reassuring story about the Allies’ raid on the French port of Dieppe on Aug. 19, 1942 which saw entire units of Canadian troops decimated by German fire is that it provided valuable lessons about amphibious tactics that turned the later Normandy invasion into a success.

But now 69 years later, a closer reading of the historical record makes clear that the disaster at Dieppe was less a learning experience on how to conduct amphibious assaults than a template for how to spin a debacle, to protect the reputations of powerful military and political figures.

The principal architect of the Dieppe fiasco was Lord Louis Mountbatten, a close relative of the British Royal family and a favorite of Prime Minister Winston Churchill who had appointed him to the important post of Chief of Combined Services.

Known to his friends as “Dickie,” Mountbatten was famous for his vanity and unbridled ambition. It was often said of him that the truth, in his hands, was swiftly converted from what it was to what it should have been.

With Churchill’s blessing, Mountbatten pushed through the Dieppe raid over the objections of many officers in the Allied military establishment who felt it was ill-advised.

Given the fact that British and other Allied troops had barely escaped from Dunkirk two years earlier, the idea of landing the mostly Canadian force on the beaches of Dieppe, have them destroy some German coastal defenses, hold the town for two tides, and then withdraw might indeed have seemed rather foolhardy.

But Mountbatten pushed for the raid as a dramatic blow against the Germans whose forces had shifted east to strike at the Soviet Union.

The landing at Dieppe about 100 miles east of the D-Day beaches of Normandy would be the first large-scale daylight assault on a strongly held objective in Europe. It also would be the greatest amphibious landing since Gallipolli during World War I another bloody disaster and it would be the first time in history tanks would land on beaches held by the enemy.

But Dieppe was to be another first as well. It would be the first big propaganda exercise of modern warfare. At the time, military-public relations were a newfangled notion, foreign to most senior British and Canadian officers.

However Lord Mountbatten’s eager P.R. team took an opportunistic view. Included on his staff were two American publicists from Hollywood, Major Jock Lawrence and Lt. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., son of the film star.

Twenty-one war correspondents and photographers were allowed to accompany the raid. What they in fact witnessed was a tragic and costly fiasco. What they wrote, after their copy was vetted by Mountbatten’s censors, was largely fiction.

For instance, the Toronto Star’s headline on the first news of the raid on Aug. 22 read: “LIKE FIREWORKS SAYS ROYAL’S SERGEANT OF BATTLE AT DIEPPE.“

The story then added: “In the grimmest and fiercest operation of the war since British troops swarmed out of Dunkirk, the Canadians’ assaulting Dieppe gave the German elite coastal defensemen a sample of the courage the Dominion’s fighting men display when they are assigned to battle.”

Years later, Mountbatten himself would frame the more pleasing conventional wisdom about Dieppe, declaring: “I have no doubt that the Battle of Normandy was won on the beaches of Dieppe. For every man who died in Dieppe, at least 10 more must have been spared in Normandy in 1944.”

Mountbatten’s self-serving analysis has remained a common lens through which to see the Dieppe raid, putting a rosy glow around the horrific losses. More than half the landing force was killed, wounded or captured without accomplishing a single major objective.

The late British historian Robin Neillands was one who cut through the propaganda that has fogged a clear understanding of the Dieppe fiasco. In his 2005 book, The Dieppe Raid, Neillands wrote, “Many of the lessons of Dieppe were quite fundamental, there was no need to learn them again at such a terrible cost.

“The Dieppe commanders failed to remember that loyalty should flow down as well as up; their loyalty was due to the nameless soldiers in the landing craft as much as to their superiors and dictates of the Service.

“There were people dying on those stony beaches; they deserved better of their commanders. Those who seek glory in war will not find it on the beaches of Dieppe. Those who seek tales of valour need look no further.”

Neillands concluded: “When the Canadians and the Royal Marine Commandos went ashore, they were going to their deaths — and most of them probably realized that fact as their landing craft took them into the assault.”

Two of the Attackers

I learned the truth of Dieppe from two veterans of the Canadian Royal Regiment who landed at “Blue Beach” that fateful August morning. Private Roy Jacques first told me the real story:

“There were 5,000 of us from the 2nd Canadian Division, 1,000 British commandos and 50 U.S. Army Rangers. In less than ten hours battle, after hitting the beach, 1,380 of us had been killed. I was captured along with 2,000 others, mostly wounded by the Germans, and spent the rest of the war at Stalag Stargard.”

(Jacques survived the war and later became a respected journalist and news director of CKWX in Vancouver.)

Another veteran of Dieppe was Private Joe Ryan of Toronto, also of the Royal Regiment. In 2007, I accompanied him for a return trip to Dieppe for the 65th anniversary of the landing.

As we walked the landing beach and visited the Canadian cemetery, he told me: “That’s my beach, Don. The tide was about the same as it is now when we ran across those damn rocks tripping and falling. See that old German pillbox is still there overgrown with weeds.”

In the cemetery, Ryan pointed and said, “There’s the grave of my signalman. Rolly Ward and I hit the beach together, but Rolly didn’t get up again. I took his watch and brought it back to his mother who never did believe he had been killed at Dieppe.”

Ross Munro of the Canadian Press had been in the same landing craft as Ryan but did not venture onto the beach where piles of the dead were mounting. Ryan expressed disdain for Munro and the other journalists.

“Those newsmen were drunken bastards and we wouldn’t have anything to do with them,” Ryan said. “Munro was a coward who never left the landing craft.”

I tried to convince Ryan that Munro had a good view of the embattled beach from the landing craft and was able to survive and return to England with his eyewitness story, which he could not have done if killed or captured by the Germans.

However, Munro and the other reporters were subject to draconian censorship by Mountbatten’s command and their published reports bore little resemblance to the facts on the bloody beaches. (Munro was author of the Toronto Star article cited above.)

Breaking P.R. Ground

While Mountbatten’s battle plan at Dieppe proved woefully inept, his P.R. plan was groundbreaking, even anticipating how to spin failure before the raid began.

Proof that Mountbatten’s command planned to use Dieppe as propaganda whatever happened on the beaches can be found in the Combined Operations files in the archives at Kew near London.

Using the code name for the Dieppe raid, a memorandum entitled “Jubilee Communiqué Meeting” makes clear that Mountbatten planned to cite “lessons learned” before any were actually learned:

“In case the raid is unsuccessful the same basic principles must hold.

1. We cannot call such a large-scale operation a ‘reconnaissance raid.’

2. We cannot avoid stating the general composition of the force, since the enemy will know it and make capital of our losses and of any failure of the first effort of Canadian and U.S. troops.

3. Therefore, in the event of failure, the communiqué must then stress the success of the operation as an essential test in the employment of substantial forces and equipment.

4. We then lay extremely heavy stress on stories of personal heroism — through interviews, broadcasts, etc. — in order to focus public attention on bravery rather than objectives not attained.”

The press releases, which were issued following the raid, followed Mountbatten’s P.R. prescription almost verbatim. “Vital experience has been gained in the employment of substantial numbers of troops in an assault, and in the transport of heavy equipment,” one communiqué read.

Classified papers in the British archives released 30 years after the battle show that

Mountbatten may have even duped Churchill and his War cabinet into believing Dieppe was a success. One report from Mountbatten read:

“The raid had gone off very satisfactorily. The planning had been excellent, air support faultless, and naval losses extremely light. Of the 6,000 men involved, two thirds returned to Britain and all I have seen are in great form.”

The actual fate of the invasion force wasn’t so cheery. Historical records show that 3,623 of the 6,086 men who made it ashore were killed, wounded or captured a loss rate of almost 60 percent.

Mountbatten even convinced Churchill to replace his original critical account of the raid in his war history, The Hinge of Fate, with a more positive one written by Mountbatten himself, according to Brian Loring Villa, a professor of history at the University of Ottawa who wrote Unauthorized Action: Mountbatten and the Dieppe Raid.

In 1974, in a speech to British war veterans, Mountbatten even accused the Canadians of changing his original plan to a frontal attack, Villa reported.

Throughout his life, Lord Mountbatten continued to work assiduously to enhance his place in history, especially regarding his leadership of the Dieppe raid. Despite some dissenting voices, he was largely successful, or at least he spared himself from any searing condemnation.

[In 1979, Mountbatten was assassinated by the Irish Republican Army in a bombing of his fishing boat off the coast of Ireland.]

Few Regrets

For his part, war correspondent Ross Munro went home to Canada after the war to become the Editor of the Vancouver Sun. He had few regrets about how his intrepid war reporting was so distorted by Mountbatten and Churchill’s censors:

“You get very deft and skilled at telling the story honestly and validly despite the censorship. I never really felt, except maybe on the Dieppe raid, that I was really cheating the public at home.”

Three years after the war ended, without the interference of censorship, Munro wrote a book Gauntlet to Overlord, in which he described the Dieppe landing from his perch aboard the ship that had also carried Private Joe Ryan to the beaches of Dieppe:

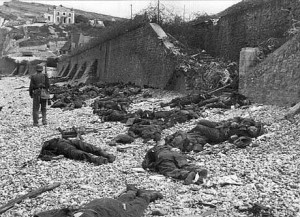

“They plunged into about two feet of water and machine-gun bullets laced into them. Bodies piled up on the ramp. Some staggered to the beach and fell.

“Looking out the open bow over the bodies on the ramp, I saw the slope leading up to a stone wall littered with Royal casualties. They had been cut down before they had a chance to fire a shot.

“It was brutal and terrible and shocked you almost to insensibility to see the piles of dead and feel the hopelessness of the attack at this point. The beach was khaki-coloured with the bodies of the boys from Central Ontario.”

Munro concluded that the raid was a complete tactical failure, that everything that could have gone wrong did go wrong, that “looking back, it seems to me to have been an incredibly risky task with only a gambler’s chance of success.”

But Munro still bought Lord Mountbatten’s positive spin, writing that “losses must be seen in the light of valuable experience gained. The battle of D-Day was won on the beaches of Dieppe.”

In an article on the 40th anniversary of the Dieppe raid, Frank Gillard of the BBC, one of the correspondents at Dieppe, expressed regret for his coverage:

“I am almost ashamed to read my report, but it was that or nothing. It was a day of wrangling, first with one censor and then with another, until our mutilated and emasculated texts, rendered almost bland under relentless pressure, was released 24 hours after our return.

“It was all so stupidly frustrating. There was sheer folly at Dieppe, but that was at the planning level. Those who had to execute these misguided orders against impossible odds showed gallantry and heroism of the highest order.

“Given half a chance, we could have presented Dieppe in terms that would have evoked pride along with the sorrow. But P.R. handling of Dieppe was as great a disaster as the operation itself.”

German Accounts

Ironically, the Dieppe story was more accurately written from the German side.

A reporter for the Deutsche Alleghenies Zeitung, who was visiting a nearby Luftwaffe air base, wrote of the Allied assault: “As executed, the venture mocked all rules of military logic and strategy.”

Even Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda, Dr. Josef Goebbels, in a radio interview monitored by the BBC, sounded rational compared to British claims of victory at Dieppe, assertions that Goebbels correctly mocked as propaganda:

“We have no doubt it is possible with this kind of news reporting to deceive and lead astray one’s own nation for a time, but we do doubt that one can alter any of the facts by such methods.”

Later, American author Quentin Reynolds, who covered the Dieppe raid for Colliers Magazine, explained some of the thinking inside the Allied press corps:

“The correspondents of the Second World War were a curious, crazy, yet responsible crew. For the sake of the war effort, and because the war against Hitler was considered a just one, they did what was required of them.”

Still, today’s murky judgment about Dieppe is summed up at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, where a citation on the wall says: “Some insist that the lessons learned at Dieppe contributed to the success of later allied landings including Normandy. Others insist that the raid was poorly planned and an avoidable blunder.”

But the larger problem about this imprecise narrative is that history is to the human race what reason is to the individual. Both extend our ability to think past the narrow present, and if they are distorted for whatever reason future misjudgements are invited.

Truth can often be painful, especially for the foot soldiers and their loved ones who wish to cling to the positive spin of terrible events. My friends Roy Jacques and Joe Ryan went to their graves last year comforted by Mountbatten’s false claim that those who fought and died at Dieppe paved the way for victory at Normandy two years later.

They can be forgiven, as can be the relatives and friends of those who died at Dieppe who desperately searched for meaning in the sacrifice and loss. It can take great personal courage to make hard and truthful judgments in wartime.

When I visited the Canadian cemetery, Alain Menue of the Dieppe memorial association, moved among the grave stones marked with a maple leaf and the date August 19, 1942, laying wreaths and flowers:

“We in Dieppe remember their sacrifice. Even though there are few lines now in the history books about the battle. It is important to remember the defeats as well as the victories.”

Cautionary Tale

In that sense, Dieppe is a cautionary tale against false patriotism. Glorified history can make war more palatable to the public, which can encourage its use again, often too readily and without regard to the real human consequences.

One lesson that today’s readers can extract from the actual history of Dieppe is to read news articles about war with a measure of skepticism and to understand that the powerful will do what they can to spare themselves from accountability for their miscalculations and hubris.

Though there is no draconian censorship of war news from Afghanistan, for instance, there is still pressure on reporters and news organizations to put the best face on events, not to be too negative.

There also is a desire to give some positive meaning to the Afghan War and the parallel conflict in Iraq, to argue that the more than 6,000 American troops and their “coalition” partners who have died did not die in vain.

But sometimes the sacrifice of these soldiers is more to advance or protect the reputations of political and military leaders than anything else.

Perhaps British poet Rudyard Kipling put it best in writing about another pointless military mission in World War I, where his own son perished: “If any question why we died, tell them because our fathers lied.”

In eulogies to fallen soldiers, there is a tendency to mark unnecessary deaths as justification for still more unnecessary deaths. Meanwhile, from senior military leaders like General David Petraeus, former U.S. commander in Afghanistan and Iraq now elevated to CIA director we hear the mantra, “there is progress in Afghanistan.”

So far this August, 50 Americans have died in Afghanistan, including 30 from the crash of a Chinook helicopter. And the rate of suicides among veterans is also at epidemic levels.

Dieppe was a case of deceitful manipulation of the press into reporting a defeat as a victory. In Afghanistan today, however, it is more a case of American journalists being almost absent from the war. With few exceptions, those who are present are covering the war the way the U.S. government presents it to them.

Last week, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard issued a report noting that “the war without end is a war with hardly any news coverage” and adding:

“TV coverage averages 21 seconds per newscast. One critic quoted says the lack of sustained American TV reporting of Afghanistan is the most irresponsible behavior in all the annals of war journalism.”

The lesson from Dieppe may be that if the “first rough draft of history” as reported in the news media is distorted, it can live on indefinitely unless there is aggressive scholarship to counter it. The question from America’s open-ended wars after the 9/11 attacks may be: what happens when journalists are not even there to write the first draft?

Don North, who was born in Canada, has been a war reporter since covering Vietnam beginning in 1965. North has known and interviewed dozens of veterans of the Dieppe raid and researched it in the British and Canadian war archives. This article is based on a chapter from the manuscript of his book Inappropriate Conduct which deals with war reporting in World War II.

Was Dieppe orchestrated as a sop to Stalin? to allow Stalin to propagandise his people toward the notion that they (the Russians) were not alone? Or maybe: Did Stalin demand a blood letting to prove fidelity? Or alternately, maybe Mountbatten, old school style, wanted to communicate fidelity without being asked?

Another possibility would seem to be the need for Allied home front to ‘know what they are fighting for’. Stalin faced a similar moral situation in the far east and orchestrated a terrible Soviet force loss at the hands of the Japanese in order, as he said later, to let his home front ‘know what they were fighting for’.

Both I think.

But there is also a backwards truth in what Mountbatten said. The British leadership really was so very bad that they did Dieppe despite many opportunities to have learned better, most recently their Narvik fiasco. British officers were many of them ill trained and self satisfied incompetents. This and a few other things like it helped clean them up a bit. They are now entirely different than they were before Dieppe, and Dieppe played an important part in making that happen.

In pressing his demands for a second front Marshall Stalin got consiserable help from British trade unions and intellectuals who were painting “Second Front Now” slogans in Trafalgar Square. By early 1942 Stalin even suggested he would negotiate with Hitler for an armistice if the Allies would not help him

by opening a second front. But the Allies were not ready to invade France in 1942 with insufficient forces and a lack of landing craft. Other priorities like the North Africa campaign and the u-boat war held the Allies to only raids on Europe.

I have seen no evidence that as wanting in leadership Mountbatten proved to be that he sought a bloodbath at Dieppe to “let the home front know what they were fighting for.” The British already had their blood letting at Dunkirk and the Americans at Pearl harbor.

Mountbatten made an effort to impress the Russians with the Dieppe raid by issuing a strong invitation to the Tass correspondent in London to report first hand on the raid. The Russian reporter declined, presumably acting on orders from the Kremlin. He said he only wanted to accompany a genuine operation to establish a second front and not just a raid. Don North

This is not an excuse, but my father was a British medical officer and he did look after the needs of Canadian forces but mostly in northern England. He looked after one who drank hard cider, unknowingly strong to him, and he fell of a building climbing the outdoor plumbing. Another incident was at gunnery training when an officer ordered a gun be fired before the mussel cover had been removed, costing several lives.

He said that the Canadian troops where bored stiff having been in the cold wet uncomfortable English climate for some time and not doing anything. Before Dieppe, they were most eager for action, making discipline more difficult. Could there have been pressure to get them active.

John, thanks for this insight on your fathers experience as a medical officer for Canadian troops before Dieppe. There is no doubt there was strong pressure, mainly from the Canadians themselves, including Prime Minister MacKenzie King to get them into action in Europe. Canadian units first arrived in England in 1940 very anxious to get into the fighting. The Canadian soldier was tough, well educated and independently minded and with little patience for formal discipline. Two years of only training took its toll. Denied action against the enemy they found it in brawling with the police, fighting in pubs and military discipline suffered. When the prospect of action at Dieppe developed Canadian Generals were delighted.There was ample evidence that the Dieppe raid would be a fiasco, but it would have taken exceptional courage for officers commanding the Canadians to have done the right thing and refused to participate. The result was the needless deaths of over a thousand troops on the landing beaches.

Don North

I bet most of you thought that Orwell’s “1984” was a work of fiction.

Truth is STILL a casualty in succeeding British conflicts. Liz Curtis in her magisterial critique of British press coverage of the NI “Troubles” “Ireland: The Propaganda War” (Pluto Press, 1984) cites a former correspondent of a British tabloid who recalls that what he remembers most about the conflict is the uncomfortable stories he heard but never published about the conduct of the security forces during the Troubles. He cites a case in which on the day of internment(August 1971) Paras and RUC men beat a Catholic man so brutally that he was taken to hospital with a fractured skull. When he phoned over his story, his editor not only refused to print the story but threatened to sack him if ever again suggested that the Army was doing such dreadful things in Northern Ireland!

In all conflicts of all armies.

Modern propaganda was made scientific by an American marketing expert in WWI to support the War to End All Wars, and this work was studied by and quoted by the Nazis.

this article was extremely interesting to me as I remember very clearly the

landing on Dieppe during the war as well as that on St.Nazaire.

Europe was occupied then and what we learned was only from German controlled

radio news and UFA newsreal showing scores of dead soldiers on the beach. I didn’t know there were 6000 troops involved. We thought there were only a few hundred soldiers only Canadians.

I might try to get North’s book “Inappropriate conduct”.

Thanks John Dotis and Randal Marlin for your comments on how effective German radio news was in WWII when they told the truth to refute frabrications on allied broadcasts. Radio news really came into its own in WWII and made it harder to effectively turn defeats like Dieppe into victories. However, even

during the Vietnam war US Armed Forces Radio ignored news of US military setbacks or protests at home while Radio Hanoi often broadcast the truth in english to our troops. Hanoi Hannah did not always tell the truth but in 1967 when USAFR ignored the anti-war riots in Detroit, Hanoi Hannah broadcast full

details. Eventually USAF readio changed to re-broadcast US network news to our troops adopting a policy to broadcast the same news to troops overseas

as was heard by civilians at home.

John, thanks for your interest in my book “Inappropriate Conduct” from which the Dieppe story was written. Unfortunately, no publisher has shown interest and I will publish it myself in the near future.

Don North

There is a dramatic episode in the National Film Board documentary, “Grierson,” about its founder, John Grierson, where he is portrayed as listening to Goebbels’ propaganda and concluding that it was telling the truth and that Dieppe was a disaster, so he sent word (in his capacity as the authority in the Wartime Information Board) to the media to play the story down.