President Trump’s proposed “Great Wall” across the U.S.-Mexican border presents particular problems for a Native American tribe whose traditional lands straddle the line, reports Dennis J Bernstein.

By Dennis J Bernstein

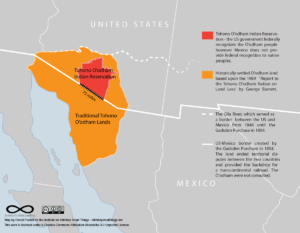

The traditional lands of the Tohono O’odham Nation cover parts of both southern Arizona in the U.S. and northern Sonora province in Mexico, making President Trump’s proposed “Great Wall” a special concern to the tribe whose U.S. reservation extends 75 miles along the border and whose tribal members live and work on both sides.

On Jan. 26, the tribe issued a press release noting that “the Nation has been on the front line of border issues for over 160 years and takes these issues very seriously. While the Nation does not support a large-scale fortified wall, it has worked closely for decades with U.S. Customs and Border Patrol and other agencies to secure the U.S. homeland.”

I spoke with Mike Flores, a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation and the American Indian Movement (AIM), who told me that Homeland Security and ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) have had a “heavy” presence in Tucson and the U.S.-Mexico border at Nogales, Arizona, since Trump signed presidential directives late last month calling for an immigration crackdown.

“Trump seems like he’s totally unaware of the damage and the desecration his wall would do to harm not only our people, but the natural environment here in our area,” Flores said. “Unfortunately, this administration has no regard for this so-called government-to-government relationship with the tribes. And, there’s been no consultation with our tribe, especially being that we’re right on the border … (which has) disrupted our way of life for decades now.”

Flores made it very clear that the new Trump directives and the wall will deeply disrupt his Nation’s way of life, as well as to endanger and kill off much of the rich natural and wildlife of the region.

“Historically, we were able to go back and forth to visit, not only relatives but sacred sites, conduct ceremonies in what is now known as Sonora, Mexico,” Flores continued.

“And that has been impeded since this border has been put in. And to see a wall going up, that would even prevent us from carrying on any of our ceremonial ceremonies, that we have in Mexico, as well as our relatives coming north to participate in ceremonies up here. That’s how it’s affected our people.

“But also, I think the wildlife in our area: the deer, the antelope, the pronged horns, the mountain goats. They are endangered by the wall. …They all have these migration areas where they go. And to have a wall going up would prevent them from doing their migratory traveling as well, which, again, would interfere with the natural way of life for the wildlife.”

Beyond those disruptions, he added, “The militarization of our tribal lands has become so bad, that yes, we can’t even go shopping without being stopped … and a lot of times, being detained for hours, without any reasons, other than that we are indigenous people of the land. And it creates a bit of concern for us, because we have had issues in the past where people were hurt or injured because of the paranoia of federal officials.”

Flores said ICE and the Border Patrol have already set up “what they call checkpoints, not only on the tribal lands but just a hundred yards off the reservation, on roads largely used by tribal members.

“These roads go to the reservation, and so anybody that drives, like, say if I was going from east to west … if I was coming into Tucson, I would get stopped just right outside the tribal reservation, and they ask if I am a U.S. citizen. They ask if I’m carrying any contrabands, WMDs, or that type of…B.S. …

”And it’s very frustrating to have to deal with these people. I’m not saying they’re all alike, but a big majority of them are … they come across like the John Waynes of the area. And it’s kind of ridiculous at times, as well.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection in Washington, D.C. during the inauguration of Donald Trump. January 20, 2017. (Flickr U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

Flores said the checkpoints have been the scene of some violent overreactions by the Feds. “People have been physically manhandled, put on the ground, handcuffed, and thrown into vehicles for hours,” said Flores. “And then they are let loose after so many hours of sitting in a border patrol van, sweating it out. That’s what a lot of our people go through, just because they want to go to Tucson to go shopping.”

“I have told government officials, not only tribal, but U.S. federal officials, that I don’t want to see this type of warfare going on in our communities, in our backyard, especially for my children, my grandchildren, that are growing up in this area,“ said Flores. “I don’t want them to have to live under this kind of rule. And, hopefully, we can eliminate those things, so that our people can really prosper the way they should be able to here, in this place called America.”

Flores also said that his Nation was deeply opposed to Trump’s expanded wall and that tribal leaders would resist its construction.

“Our vice chairman, Verlon Jose, said, ‘over my dead body will a wall be built. I do not wish to die, but I do wish to work together with people so that we can truly protect the homeland of this place they call the United States of America, not only for our people but for the American people,’ I think, was his exact quote. That he would do, and go to that extreme, to prevent a wall from going up. And I think that kind of resonates the sentiments of many, if not all our tribal members.”

Dennis J Bernstein is a host of “Flashpoints” on the Pacifica radio network and the author of Special Ed: Voices from a Hidden Classroom. You can access the audio archives at www.flashpoints.net.