After World War II, U.S. prosecutors at the Nuremberg Tribunals deemed aggressive war the “supreme international crime” because it unpacked all the other evils of war. But Official Washington now treats U.S. invasions of “enemy” states as a topic for casual political discourse, as ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar notes.

By Paul R. Pillar

Amid much talk lately about “red lines”, to the point that the term would be a strong candidate for cliché of the year, we should reflect on the relative inattention, as Richard Falk points out in a recent commentary, to what used to be one of the most fundamental and important red lines of all.

The line in question, which Falk notes the United States once played a leading role in formulating, is “the prohibition of the use of international force by states other than in cases of self-defense against a prior armed attack.”

Falk has been around long enough to rile adversaries on many issues about which he has been outspoken (and I have disagreed with some of his past positions). It was nearly 40 years ago that I took a graduate course in international law from him, and he is now in his 80s. But he does speak some uncomfortable truths.

Many he has spoken in connection with his current function as the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories. Most recently he incurred irresponsible vitriol, including some from U.S. officials, when he noted, accurately, that U.S. policies have something to do with stimulating the kind of violent extremism exhibited by the Boston Marathon bombers.

His observation about disregard for the once-prominent norm against aggression gets to another set of truths. Erosion of respect for this norm, specifically in discussions of U.S. policy, is a recent phenomenon. Throughout the Twentieth Century the United States largely observed it, and as far as significant warfare is concerned rigorously observed it.

Moreover, the United States expended much blood and treasure in campaigns that, whatever other U.S. interests they may have served, were responses to someone else’s aggression and ensured that the aggression would not be allowed to stand. World War II was the largest such effort; Korea in 1950 and Kuwait in 1990-91 were others. The U.S. response to the Anglo-French-Israeli attack on Egypt in 1956 was an example of upholding the norm of non-aggression even when it meant opposing close allies.

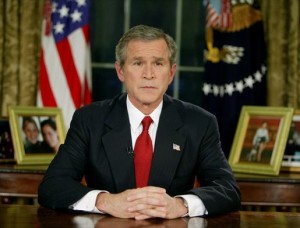

The big departure that led the United States astray from this path was the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the first significant U.S. war of aggression since the Nineteenth Century. Despite the costly unpleasantness that followed the invasion, this episode seems to have had a lasting effect on American debate in extending the range of respectable policy options to include ones that earlier would have been ruled out as being beyond the red line of non-aggression.

Most Americans of just a couple of decades ago, even after the Soviet Union imploded, would have been taken aback by how much some beyond-the-line possibilities, such as an unprovoked attack on Iran, are deemed respectable enough to be seriously considered today.

Falk does not discuss non-aggression in absolute terms. He suggests that in individual cases other considerations, such as humanitarian ones, often appropriately come into play. He also appears to accept the frequently-advanced (though not necessarily valid) idea that we are living in an era in which the ubiquity of terrorism means some rules of international conduct need to be revised.

His principal lament is that the rule of non-aggression is not being carefully updated but instead simply abandoned. That, he says, means “normative chaos,” which “in a world where already nine countries possess nuclear weapons seems like a prescription for species suicide.”

That’s probably putting the point too strongly, but such a world is nonetheless not in U.S. interests. The United States, despite (and as the Iraq War experience suggests, perhaps even because of) its standing as the militarily most powerful state, has more to lose than to gain in such a world.

Restoring, respecting, and fostering a norm of non-aggression is in the interest of the United States even if one does not approach the subject, as Falk does, with an emphasis on international organizations and international law. Even the most hard-boiled realist, focused like a laser on U.S. national interests, can see the benefit to the United States of having such a norm.

This leads to part of an answer to the question that Danielle Pletka posed and Jacob Heilbrunn highlighted as a fair question to realists: what do they want, as distinct from what are they against? They ought to want a world in which states do not start wars whenever and wherever they feel like it.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

The US’s “Wars of Agression” can be traced back to American exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny; the idealism is deeply engrained in America. Aggresion serves the shortsighted goals of free markets and resources.

“the first significant U.S. war of aggression since the Nineteenth Century.”

Excluding the Phillipine-American War, Boxer Rebellion, WW1, Korean War, Vietnam War, and the other lesser known occupations???

The fbi/cia & company (traitorous assassins all) have ruined our nation and now threaten all the world. See the following statements from Cicero where he captures the essence of a universal truth regarding the destructive power of traitors (brackets and the contents therein are mine).

Marcus Tullius Cicero

“A nation … cannot survive treason from within…the traitor moves amongst those within the gate freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself [in congress, the courts, the executive offices]. For the traitor appears not a traitor; he speaks in accents familiar to his victims, and he wears their face and their arguments, he appeals to the baseness that lies deep in the hearts of all men. He rots the soul of a nation, he works secretly and unknown in the night to undermine the pillars of the [nation], he infects the body politic so that it can no longer resist. A murderer is less to fear.â€

http://vancouver.mediacoop.ca/story/age-madness-critical-review-fbicia-operations/9375

http://www.sosbeevfbi.com/911caneasilyrevi.html

http://www.sosbeevfbi.com/part4-worldinabo.html

http://portland.indymedia.org/en/2008/11/382350.shtml?discuss

Power corrupts.

I remember when G.W.Bush called himself “WAR PRESIDENT”

The congress is supposed to be check on the president,

They are failing at that.

The toll is enormous. Just look at our casualties.

With all that nuclear weaponry, the future of humanity

is in peril.